The pandemic continues to affect workforce supply through its wide-ranging impacts, including on migration, workforce availability, labour mobility and work placements. Compounding the impacts is the lower proportion of people aged 15-64 who are available to meet the growing demand for workers.

The closure of international borders has restricted new arrivals

Prior to the pandemic, Victoria averaged nearly 88,000 net arrivals from overseas per year. During 2021 Victoria experienced net departures of approximately 56,000.4

Internal migration patterns are similar. In 2021, 18,000 more people left Victoria than arrived from other states and territories, compared to net arrivals of approximately 47,000 total across the previous 4 years.5

These factors contributed to Victoria’s population falling for the first time in almost 30 years. There were 160,000 fewer working age people in Victoria in 2021 compared to pre-pandemic forecasts – equivalent to around 2 years’ workforce growth under historical trends.6,7

There are several regional local government authorities, however, that had net internal migration growth over 2020–21, including Ballarat, Bass Coast, Baw Baw, Greater Bendigo, Greater Geelong, Mitchell and Surf Coast.

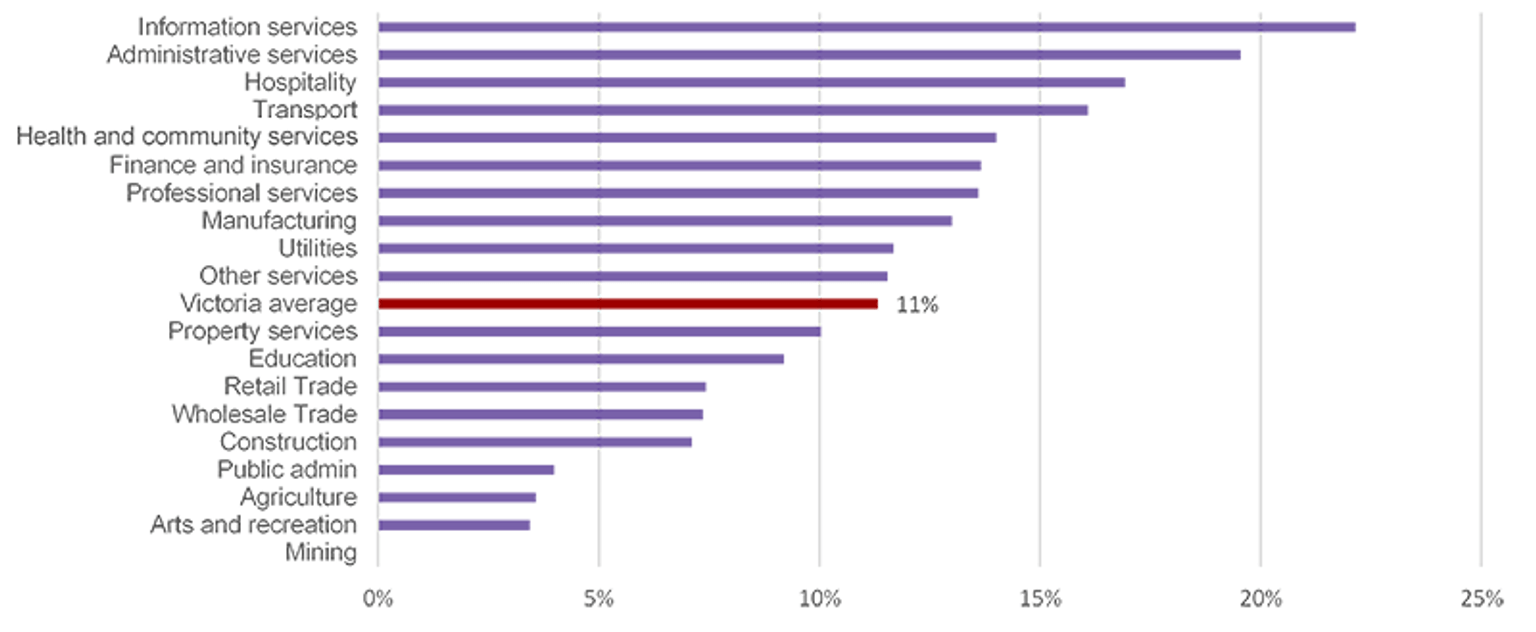

The impact on industries has varied, with those most reliant on overseas migration such as accommodation and food services and agriculture (primarily the seasonal workforce) more affected (refer Figure 4). All industry groups consulted for the Victorian Skills Plan identified migration as critical for meeting specialised skill needs.

The pandemic continues to disrupt workforce dynamics

The pandemic presents a once in a generation challenge. As infections increased, many employers reported between 10% to 20% of their workforce were unable to work8,9 or needing to care for others who had contracted COVID-19.

With the virus transitioning from pandemic to endemic10, absenteeism could remain a challenge for at least the next 12 to 18 months.

The rate of supply of new entrants to the workforce from students completing their studies has also been impacted and will continue to be by pandemic disruptions. Many students face barriers to securing work placements required to complete their qualification. Several health and community services qualifications require mandatory work placements, yet lockdowns and other restrictions made it difficult for worksites that typically take students to do so. There is a risk that these students will chose not to complete their qualification and will be lost from the industry.

Increasing movements of people within the labour market contribute to a dynamic economy, but can be unsettling for those employers who need to find replacements, especially on top of worker shortages. In 2021 there was record low job mobility11 with workers prioritising job security over risking a move to a new job, even though it may better suit their skills and education levels. Recent data shows mobility may be returning – the number of workers who left their job for a better job or change in the last 3 months to-date is 45% above pre-pandemic levels.12 In addition, the percentage of employed people who do not expect to be with their current employer or in business in the next 12 months is at the highest level in 20 years13 and the number of people expecting to change jobs or seek other employment is 10% above pre-pandemic levels5.

These factors will continue to impact employers’ ability to secure the workforce they need to meet immediate and expected demand.

Demographic change presents structural challenges

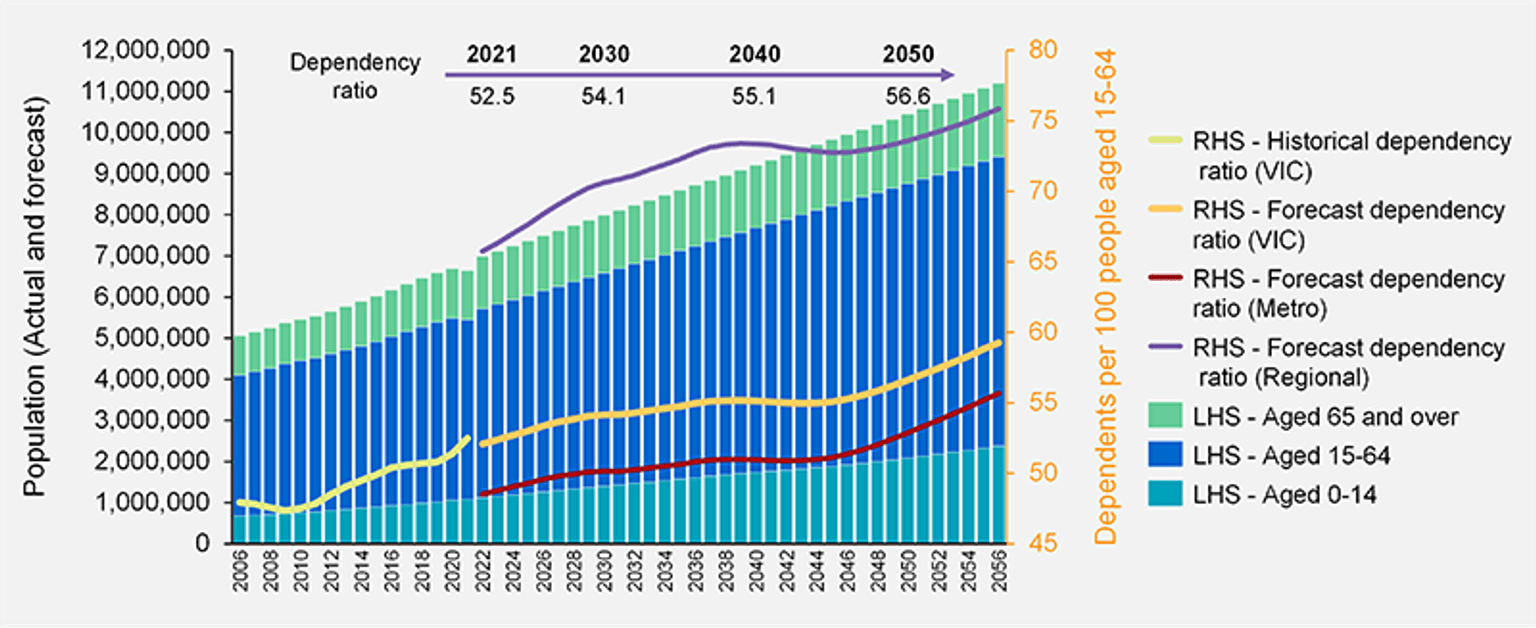

The temporary impacts of the pandemic mask a deeper challenge for the Victorian economy – the share of working age Victorians is not keeping pace with the overall population. While population increases fuel growth and employment demand, a decreasing proportion of individuals aged between 15 and 64 are available to meet this demand.

In 2021, the number of non-working age people relative to working aged people was 52.5 to 100. This is expected to increase year-on-year to a high of 56.6 in 2050 (refer Figure 5).14 In regional areas the gap is larger, with the number of non-working age people relative to working aged people growing substantially, from 65.7 to 100 in 2022 to 73.6 to 100 in 2050.

These increasing dependency ratios indicate fewer individuals available to do the work required to meet employment demand triggered by the overall population. They also indicate that those outside of working age – either children and young people and retirees – typically need higher levels of support, either in education or health and aged care.

References

4 Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2022, Regional population, Population components by LGA, 2016–17 to 2020–21, reference period 2020–21 financial year, released March 2022, ABS, Canberra

5 Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2022, Regional population, Population components by LGA, 2016–17 to 2020–21, ABS, Canberra.

6 Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP) 2021, Victoria in future 2019(opens in a new window) population projections, DELWP, Melbourne.

7 Australian Bureau of Statistics 2022, National, state and territory population, reference period September 2021, released March 2022, ABS, Canberra.

8 Herald Sun News, Daily case numbers drop as Omicron peaks, 2022.

9 Guardian News, A game of Russian roulette Victoria’s Alfred hospital expects 15% staff absent at COVID peak, 2022.

10 The Conversation, COVID will soon be endemic. This doesn’t mean it’s harmless or we give up, just that it’s part of life, 2022.

11 Australian Bureau of Statistics 2022, Participation, Job Search and Mobility, Australia, cat.no. 6223.0, reference period February 2022, released May 2022, ABS, Canberra.

12 Australian Bureau of Statistics 2022, Insights into job mobility from quarterly Labour Force Statistics, released March 2022, reference period February 2022, ABS, Canberra.

13 Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2022, Labour Force, Australia, Detailed, Table 17, reference period March 2022, released April 2022, ABS, Canberra.

14 Australian Bureau of Statistics, National, state and territory population, reference period June 2021, released December 2021, ABS, Canberra.

Updated