- Date:

- 24 Apr 2023

Overview

Supervision is central to developing and sustaining family violence, sexual assault and child wellbeing workforces.

It allows the exploration of:

- roles and responsibilities of sector practitioners, including risk assessment, therapeutic support, engagement, safety planning and collaborative multi-agency responses to family violence

- roles and responsibilities of supervisors

- adult, child and young person victim survivors’ experience and narrative and how to work in a nuanced way with young people who can be both victim survivors and use family violence

- respecting victim survivors as experts of their own lives and valuing their assessments of their own safety and needs

- how to practise safe, non-collusive communication with perpetrators

- inviting personal accountability for perpetrators’ use of family violence and sexual violence, and their related failure to protect children by using violence

- both perceived and real risks to supervisee’s safety, including fears practitioners have working directly with perpetrators or providing afterhours outreach services1

- applying an intersectional lens and understanding supervisee/supervisor biases, including how people from First Nations, LGBTIQA+, culturally diverse communities or at-risk age groups may experience barriers, discrimination and inequality

- providing practitioners with lived experience of family violence and sexual assault with practice support and encouragement to practise self-care

- providing First Nations practitioners with support to carry the cultural load

- how to embed cultural safety, in line with the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural safety framework2

- providing First Nations practitioners with support to carry the cultural load

- how a supervisee's family of origin3 or creation may affect their client assessments and interactions

- how to be more strengths-based and collaborative with clients, colleagues and other professionals

- individual practitioner and organisational power, and structural and systemic privilege and oppressions across the sector4

- the multi-faceted nature of supervision, including reflection, case discussions, support, professional development, clinical and managerial functions.

The sector has a highly skilled, dedicated, and resilient workforce, who, for decades, have embraced the importance of supervision and reflective practice (active process of witnessing an experience, examining it, and learning from it). The prevalence and severity of family violence have escalated. This, combined with the prescribed responsibilities under the Family Violence Multi Agency Risk Assessment and Management (MARAM) Framework, including a greater focus on collaborative practice and intersectionality, means providing effective supervision has never been more crucial.

Written in collaboration with the sector, the following information can be used ahead of the full Best-practice supervision guidelines (the guidelines), to be published online in 2023. The guidelines are a commitment of the 10-year industry plan and the First rolling action plan.

The information does not set out to change what is already working within the sector, but will:

- provide an opportunity for programs and organisations to review their supervision policies and practices and consider sector thinking and what other programs have found useful

- apply to family violence, sexual assault and child wellbeing sectors, acknowledging that these workforces have different skill sets and role requirements

- set the foundation for achieving more uniform, standard definitions, models, principles and practices of supervision across the state

- explore complex concepts and theories in terms of how they relate to supervision and provide further reading if the sector wants to delve deeper

- contribute to the commitment Government made in the Dhelk Dja Partnership Agreement of ensuring self-determined, strengths-based, trauma-informed, and culturally safe practices are built into policies and practice, and the broader family violence service system and its workforce

- signal to potential graduates and career changers entering the family violence and sexual assault workforces that their learning, support and wellbeing needs will be taken seriously

- support a culture of learning and professional growth

- invigorate conversations about best practice and some of the tensions and challenges inherent in providing regular and effective supervision.

There is information on:

These topics were chosen based on discussions with the sector and the fact that they form foundational pieces, from which more complex concepts can be explored.

The information is intended to be used during individual, group or peer supervision sessions, policy development and supervision training.

'Paying attention to improving supervision quality can have far-reaching effects and be one of the most cost-effective ways of turning around an organisation.' —Wonnacott, 20125

Footnotes

1 Family Safety Victoria, Family violence multi-agency risk assessment and management framework, Victorian Government website, 2018, accessed 27 Feb 2023.

2 Department of Health and Human Services, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural safety framework, Department of Families, Fairness and Housing website, 2019, accessed 24 Feb 2023.

3 B Lackie, ‘The families of origin of social workers’, Clinical Social Work Journal, 1983, 11 (4): 309-322, DOI:10.1007/BF00755898.

4 Family Safety Victoria, Family violence multi-agency risk assessment and management framework.

5 J Wonnacott, Mastering Social Work Supervision. Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London, UK 2012.

Supervision definitions

This information was co-created with the sector and is available for the family violence, sexual assault and child wellbeing workforces to enhance consistency of language and enhance an agreed understanding of the terms used

Background

This Information provides the family violence, sexual assault and child wellbeing sector (the sector) with key definitions of supervision.

Definitions

Defining supervision within the sector is complex. It is difficult to capture the intricate balance required to develop and maintain trusting professional relationships.

Ideally, supervision offers supervisees authenticity by talking openly about emotional responses to processing stories of family violence and sexual harm.

Supervision is an essential support for practitioners who:

- invite engagement and directly (or indirectly) work with adults and young people using family and sexual violence, while applying non-collusive practice

- often work with unpredictable and serious levels of risk related to adults, children and young people experiencing violence

- may feel responsible to stop violence or abuse, and to get justice for clients, especially for practitioners with lived experience of family or sexual violence.

Supervisors have a complex role. They must balance supporting practitioners, clients’ needs and ethical practice. Supervision creates opportunities to discuss these tensions, and to support and sustain practitioners in their challenging, complex work.

Supervision

Supervision is an interactive, collaborative, ongoing, caring and respectful professional relationship and reflective process. It focuses on the supervisee’s practice and wellbeing. The objectives are to improve, develop, support and provide safety for practitioners and their practice.1 It is ideally strengths-based and supervisee-led, where the supervisor adapts to supervisees’ preferences.

The sector expects supervision to incorporate an intersectional feminist lens. This allows discussion about power differences within the supervisory relationship, practice with clients and the broader system. It helps promote justice-doing, advocacy and community activism on behalf of clients and workforces.

Supervision enables monitoring of supervisee wellbeing and providing tailored support. Using a trauma and violence-informed approach allows supervisors to normalise practitioner reactions to working within an imperfect system and working with people experiencing trauma and significant life events. The emotional toll of the work and vicarious trauma can be acknowledged during supervision in an empathic, understanding way, rather than blaming or pathologising.

Supervision supports a collaborative approach with clients, especially when setting goals, developing care plans and reviewing therapeutic objectives. It also provides a forum to:

- consider the unique professional development needs and preferences of each supervisee

- adopt a variety of supervisory styles (teaching, mentoring, coaching)

- consider child-centred approaches alongside the application of an intersectional feminist lens

- reflect on interpersonal boundaries,2 essential in family violence and sexual violence work.

'Supervision is vital to recognising and valuing the skills and capacity of practitioners.' —Jess Cadwallader, Principal Strategic Advisor, Central Highlands

The sector often refers to managerial or line management and clinical supervision. The above definition aligns to both, and they are defined in more detail below.

Managerial or line management supervision

This supports organisational requirements and processes for practitioners to do their jobs and achieve positive outcomes for victim survivors.

Usually supervisor-led, this type of supervision is more task-focused and less reflective. When it includes reflection, it’s usually for technical and practical aspects rather than deeper critical or process levels.3 Managerial supervision helps align practices with organisation policies and relevant legislation. It includes discussing future career pathways and learning opportunities, both formal and informal.

Clinical supervision

Clinical supervision aims to develop a supervisee’s clinical awareness and skills to recognise and manage:

- personal responses

- value clashes

- power imbalances

- ethical dilemmas.4

Usually supervisee-led, this type of supervision allows deeper insight to the work using process reflection.5 This is where conscious and unconscious aspects of practice and supervisory relationships are explored.

A clinical supervisor can be from outside of the organisation or be an internal line management supervisor or a supervisor who does not have line management responsibilities.

Having distinct roles for clinical and managerial supervision can help ensure critical and process reflection occurs.

'Supervision is their time, it’s not my time.' —Ivy Yarram, Yoowinna Wurnalung Aboriginal Healing Service

Collaborative supervision

Supervision has traditionally been viewed as a relationship and process between one supervisor and one supervisee. This can put the supervisor in an unrealistic ‘expert’ role and one leader is unlikely to have the required skills and knowledge to meet all the needs of each supervisee.

There has been a shift to embracing a more collaborative model of supervision. There can be benefits from using multiple supervisors, as well as peer supervision. For example, The Orange Door networks developed a matrix model of supervision that incorporates home agency supervisors and practice leaders. This offers more expertise and consultation. Supervision agreements can assist in clarifying confidentiality, roles and communication channels in collaborative supervision.

Cultural empowerment

Cultural empowerment6 is a reflective, holistic, validating, non-judgemental, two-way learning process provided by a supervisor who is skilled, experienced, caring, respectful and knowledgeable about their local First Nations community.7 The relationship should empower supervisees by reducing barriers for First Nations supervisees to perform their duties in a culturally safe environment.

Culturally appropriate empowerment is needed by Aboriginal workforces in Victoria.8 It provides cultural context when reflecting on practice. It incorporates a strength-based and person-centred approach which acknowledges a supervisee’s sense of pride and purpose in being able to impart cultural knowledge to others. It is recommended for First Nations supervisees and non-Aboriginal supervisees who work with First Nations people and communities.

To be effective, supervisors and colleagues need to understand why culturally safe empowerment is important. This requires awareness and understanding of the history and subsequent issues and challenges for First Nations supervisees. Such challenges include working closely with their own community and carrying the ‘cultural load’.

Supervisors and colleagues should have appropriate cultural awareness training to be aware of their roles and responsibilities when working alongside First Nations supervisees. Non-Aboriginal services need to also recognise that some aspects of cultural empowerment and connection can only be gained and shared between First Nations people. Cultural meaning and practices will be different from non-Aboriginal norms and belief systems.9

The Yarn Up Time and the CASE model10 offer guidance on how to provide culturally responsive supervision for First Nations practitioners and non-Aboriginal practitioners working with First Nations communities.

Intersectional feminist supervision

This recognises how different aspects of a person’s identity might affect how they experience the world and the related barriers.11 An intersectional feminist lens encourages supervisors and supervisees to question their own experiences and how they might create assumptions about another’s experience. It assists supervisees to:

- better understand how different forms of marginalisation impact others

- reflect on own lived experience of power, privilege and oppression and the impacts on work with clients and other professionals12

- consider the system more broadly

- be more targeted in their advocacy for improving gender and broader equality.

It also helps practitioners appreciate the need for personalised and tailored solutions.

The message that ‘personal is political’13 is critical, as is the role of the supervisor to create this awareness for the supervisee. Supervisors can use supervision to examine the effect of hierarchies and the power differential between the supervisor and supervisee. The aim is to create a more empowering and egalitarian relationship.14 The notion that the ‘personal is professional’ and bringing your whole self to work can also be considered a feminist act.15

Link with other supports

Although they overlap, supervision is different to formal debriefing, critical incident management, day-to-day management interactions and performance management. These need their own policies and procedures. Performance management is also separate to supervision but through early recognition and support, supervision can prevent performance concerns growing.

Supervisors need to use empathy and counselling skills during supervision. How much will depend on the situation and supervisee. The line between supervision and counselling is fluid. It reflects supervisees bringing their ‘whole selves’ to the work. Personal experiences can support the work. This deep reflection provides opportunities to:

- unpack personal experiences that affect practice and vice versa

- allow supervisees to feel supported and maybe seek ongoing external help if required, through Employment Assistance Program (EAP) or therapy

- monitor the safety and wellbeing of supervisees, their levels of vicarious trauma and possible burn out.16

Develop a supervision agreement early in the relationship. This provides an opportunity to discuss the fluid nature of supervision and normalise the potential need for EAP or therapy.

'One of our practitioners wasn’t sure why a particular client triggered her. We were able to talk it through in the moment and when we unpacked it, it went right back to her early years. Providing space for in-the-moment supervision meant that she was able to make that link. I then referred her to the EAP, so she had the opportunity to explore it further through ongoing therapeutic work with someone else.' —Kelly Gannon, Team Leader, Winda-Mara Aboriginal Corporation

Footnotes

1 W O’Donoghue, cited in CE Newman and DA Kaplan, Supervision essentials for cognitive-behavioural therapy, American Psychological Association, 2016, doi:org/10.1037/14950-002.

2 National Association of Services Against Sexual Violence, Standards of practice manual for services against sexual violence, 3rd edn, 2021, accessed 27 February 2023.

3 G Ruch, ‘Relationship-based practice and reflective practice: holistic approaches to contemporary child-care social work’, Child and Family Social Work, 2005, 10 (2): 111-123, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2206.2005.00359.x.

4 State of Victoria, 2019-20 Census of workforces that intersect with family violence, Victorian Government website, 2021, accessed 27 February 2023.

5 Ruch, ‘Relationship-based practice and reflective practice: holistic approaches to contemporary child-care social work’.

6 Note that the word supervision can have negative connotations of control and regulation for the First Nations workforce.

7 Victorian Dual Diagnosis Education and Training Unit, Our Healing Ways: A Culturally Appropriate Supervision Model for Aboriginal Workers, Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet, 2012, accessed 27 February 2023.

8 Victorian Dual Diagnosis Education and Training Unit, Our Healing Ways: A Culturally Appropriate Supervision Model for Aboriginal Workers.

9 Western Sydney Aboriginal Women’s Leadership Program, Understanding the Importance of Cultural Supervision and Support for Aboriginal Workers, 2013, accessed 27 February 2023.

10 T Harris and K O’Donoghue, ‘Developing Culturally Responsive Supervision Through Yarn Up Time and the CASE Supervision Model’, Australian Social Work, 2019, 73(5):1-13, doi: 10.1080/0312407X.2019.1658796.

11 International Women’s Development Agency (IWDA), What does intersectional feminism actually mean?, IWDA website, 2018, accessed 27 February 2023.

12 Domestic Violence Victoria , Code of practice: principles and standards for specialist family violence services for victim-survivors, Safe and Equal website, 2nd edn, 2020, accessed 6 October 2023.

13 C Hanisch, ‘The personal is political’, in S Firestone and A Koedt (eds), Notes from the second year: women’s liberation, Radical feminism, New York, 1970.

14 CA Falender and EP Shafranske, ‘Psycho-therapy based supervision models in an emerging competency-based era: A commentary’, Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 2010, 47(1): 45-50, doi: 10.1037/a0018873.

15 A Morrison, The Personal is the professional, Hook & Eye website, 2010, accessed 27 February 2023.

16 D Hewson and M Carroll, Reflective practice in supervision, MoshPit Publishing, Hazelbrook, NSW, 2016.

Supervision functions

This information was co-created with the sector and is available for the family violence, sexual assault and child wellbeing workforces to help explain the functionality and provision of supervision.

Background

This information was written with the family violence, sexual assault and child wellbeing sector (the sector).

It is best understood alongside the broader guidelines, supervision definitions and reflective supervision information sheets.

It explains the purpose of supervision within the sector. Use this document during initial supervision sessions and when discussing supervision agreements.

There are many definitions of supervision (refer to the supervision definitions information sheet), but supervision broadly refers to professional development that promotes best practice for professionals working in human services.

Supervision functions are often incorporated within supervision models. Some examples include the PASE1, 7-eyed2 and 4x4x43 supervision models.

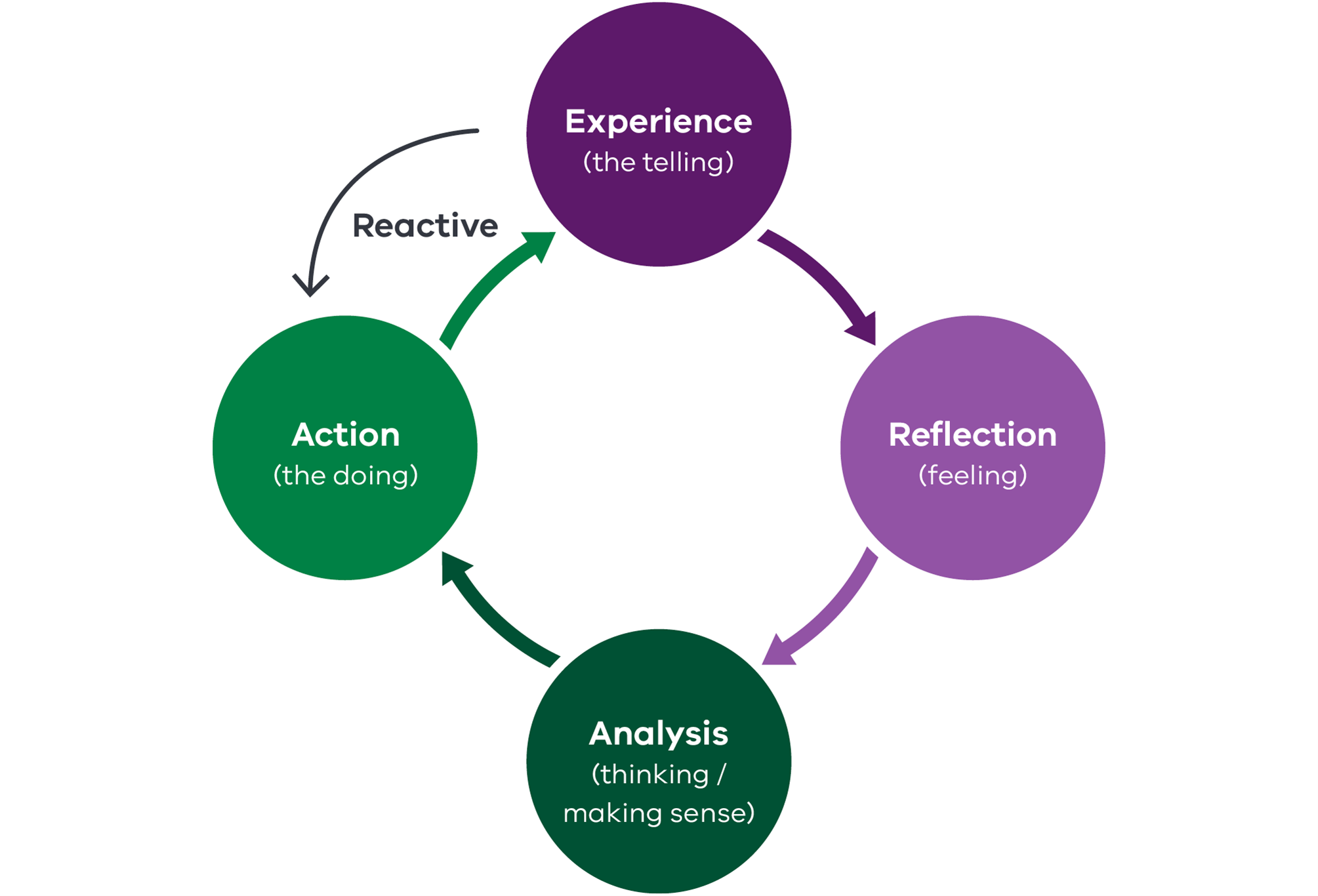

The 4x4x4 integrated model of supervision is used in many Victorian sectors, including child protection. It includes the three functions (support, management, and development) outlined in the Australian Association of Social Workers Supervision standards.4 The 4x4x4 model helps to promote reflective supervision and locate it within the context within which supervision occurs by including:

- the four functions of supervision (support, management, development and mediative)

- the Kolb learning cycle (experience, reflection, analysis, plan and act) that underpins reflective practice

- the context in which supervision occurs or stakeholders.

The supervision functions provide the ‘what’ of supervision. The stakeholders are the ‘who’ or ‘why’ in supervision. The reflective learning cycle is the ‘how’, or the glue that holds the model together. It ensures supervision is a developmental process which improves supervisee practice and decisions, as well as their insight about themselves and their work.

Four functions of supervision

Supervision serves several functions. These overlap and occur to varying degrees depending on the context, supervisory relationship and organisation. A clear separation of the functions is never entirely possible, or desirable.

It can be difficult for supervisors to cover all four functions. Sector feedback and related literature show that there is often a lack of balance across the functions, with managerial supervision prioritised. Partly for this reason, some family violence and sexual assault programs have separated clinical (supportive, developmental and systemic functions) from line management (managerial function) supervision. They have also provided peer supervision to ensure these more reflective functions occur.

The four functions of supervision are outlined in more detail below. Note that the sector prefers the term ‘systemic’ over ‘mediative’.

Supportive

- provides a forum to discuss confidentiality, develop trust and a supervisory alliance between supervisor and supervisee

- creates a safe context for supervisees to talk about the successes, rewards, challenges, conflicts, uncertainties, and emotional impacts (including vicarious trauma) of the work and to monitor supervisee safety and wellbeing

- provides an opportunity to explore vicarious resilience which can have significant and positive impacts on practitioner wellbeing and satisfaction since it identifies client strengths and signs of progress5

- explores supervisee’s own personal experiences (including current and previous trauma and lived experience), assumptions, beliefs, and values and how these can impact, and be used, in client practice and interactions with colleagues6

- works from the premise, and is sensitive to the reality, that many practitioners will have their own lived experience of family violence and sexual assault and the decision to disclose is a personal one7

- provides a space to recognise the impact of the work and identify when external supports may be needed such as Employee Assistance Programs, clinical supervision or a therapeutic response

- helps maintain professional boundaries which are critical in sustaining the workforce

- engages the supervisee and supervisor in discussions about trauma and violence-informed theory and practices, organisational culture and creating psychological safety

- recognises the potentially distressing and stressful nature of the work

- gives practitioners a restorative space to explore the impact of the work on their mental health, identity and work-life balance

- allows discussion about team wellbeing and how collective care can be enhanced.

'Always lead with care and curiosity.' —Lisa Robinson, Executive Manager, Meli

Managerial

- promotes competent, professional and accountable practice

- checks supervisee understanding and compliance with policies, procedures and legislated requirements

- monitors workloads, hybrid working arrangements and work-life balance

- checks that the supervisee has the information and resources they need

- helps supervisees understand their role and responsibilities

- reflects on interpersonal boundaries and the work

- includes human resource tasks, such as leave requests.

Developmental

- establishes a collaborative and reflective approach for life-long learning

- focuses on professional development

- supports those working to meet mandatory minimum qualification requirements

- helps embed the Family Violence Multi Agency Risk Assessment and Management (MARAM) Framework and best interests case practice model for vulnerable children and young people into practice

- clarifies individual learning styles, preferences and factors affecting learning

- explores supervisee knowledge, ethics and values

- enables two-way constructive feedback and learning between supervisor and supervisee

- allows feedforward, which focuses on future behaviour and can be better received than feedback

- allows supervisors to coach more experienced practitioners via curious, reflective questions

- helps determine and support supervisee professional development or training needs.

Systemic

- explores power structures and inequalities in the work context and the supervisory relationship

- supports discussions about intersectional feminist theory, how intersectionality is contextual and dynamic, and requires ongoing reflection and analysis of power dynamics

- ensures culturally safe and informed supervision is available to First Nations practitioners, which recognises the extra layer of vicarious trauma that First Nations practitioners are exposed to and the cultural load they carry

- recognises that there is systemic discrimination and racism that is part of the cultural load an Aboriginal practitioner must carry in their work

- helps supervisees make sense of, relate to and navigate the broader system, sector changes and system limitations

- helps improve multi-agency collaboration

- provides a forum to consult about policies and organisational change

- provides important upward feedback about the frontline experience and interface with the system

- offers a forum to plan advocacy work on a systemic level.

'We do not store experience as data like a computer: we story it.' - Winter, 19888

Footnotes

1 Amovita International, Home page, Amovita website, n.d., accessed 13 February 2023.

2 P Hawkins and R Shohet, Supervision in the helping professions, Open University Press, McGrow Hill Education, 2006.

3 Australian Association of Social Workers (AASW), Supervision Standards, AASW website, 2014, accessed 13 June 2023.

4 T Morrison, Staff supervision in Social Care, Pavilion, Brighton, 2006.

5 D Engstrom, P Hernandez and D Gangsei, ‘Vicarious resilience: a qualitative investigation into its description’, Traumatology, 2008, 14(3):13–21. doi:10.1177/1534765608319323.

6 D Hewson & M Carroll, Reflective Practice in Supervision, MoshPit Publishing, Hazelbrook, NSW, 2016.

7 D Mandel and R Reymundo Mandel, 'Coming 'out' as a survivor in a professional setting: a practitioner's journey', Partnered with a survivor podcast, 2023.

8 Winter, cited in G Bolton, ‘Reflective practice: an introduction’, in G Bolton and R Delderfield (eds), Reflective practice in writing for professional development, 2nd edn, Sage, London, 2009.

Reflective supervision

This information was co-created with the sector and is available for the Family violence, sexual assault and child wellbeing workforces to help explain what we mean by, and how we can enhance, reflective supervision.

Background

This Information provides the family violence, sexual assault, and child wellbeing sector (the sector) with a practical and useful overview of reflective supervision.

Why is reflective supervision so important?

Reflective supervision is particularly important for the sector because:

- These workforces are exposed to unique psychological health, safety and wellbeing risks. We must recognise and normalise the impact on practitioners’ emotions, behaviours and reactions. Vicarious trauma and employee burnout are widespread issues.

- Practitioners work on a micro level to address structural and systemic problems. They may experience fatigue and burn out as a result.

- Systemic discrimination and racism in Australia mean extra health, safety and wellbeing impacts on First Nations practitioners and those from diverse communities. These practitioners often work with their own communities and carry a ‘cultural load’.

- Person-centred practice is dependent on the quality of relationships between practitioners and clients. This includes being able to develop rapport, trust and empathy. It includes bringing the ‘whole self’ to practice.

- It is healthy to discuss experiences and feelings related to working with risk, uncertainty, anxiety, engagement and decision-making.

- Supervisors play a crucial role in developing, sustaining and retaining the workforce. They need their own reflective supervision to model the process and grow as leaders.

'The only way to prevent being affected would be to eliminate human relationships and emotions by becoming a robot. This would exclude the best of what we bring to our work – ourselves.' —Hewson and Carrol, 20161

Reflective supervision

Supervision creates space for reflective practice.2 Reflective supervision counters privileging thinking, efficiency, logic, formal knowledge and theories over emotions and facilitates a deeper examination of the work. In a trusting relationship, supervision focuses on being proactive in practice and decision-making, instead of reactive. Practitioners may not be aware of their feelings and subsequent reactions. Reflective questioning can ensure we recognise and process them.3

'A focus on managing ‘the doing’ rather than on developing ‘the feeling’ and ‘thinking’ aspects significantly contributes to practitioners feeling unsupported by their supervisors.' —Gibbs, Dwyer and Vivekanandra, 20144

In one-to-one reflective supervision, the supervisee leads the reflective supervision session. The supervisor suggests areas to explore. They assist the supervisee to find their own wisdom, rather than giving advice or direction. To encourage deep reflection the supervisor notices, challenges and invites the supervisee to be mindful of their actions and assumptions in a way that is non-judgemental, positive and hopeful.5

'If supervisors do not prioritise supervision, neither will staff.' —Jacky Tucker, State-wide RAMP Coordinator, Safe & Equal, 2023

Regular reflective supervision should be prioritised within organisations.6 Time is a precious commodity in fast-paced, busy organisations, which is at odds with the slow, thoughtful space needed for reflective supervision. To engage in deep reflection, supervision needs to occur in a private and suitable location. Supervisees must feel they have the time to explore subjects and feelings uninterrupted and be truly present. (Some supervisors set aside two hours for this.)

During peer or group supervision, there needs to be a high level of psychological safety for deep critical and process reflection. For this reason, reflective practice often works best in a closed group setting. This provides the group with time and regular contact to build familiarity and trust.

What is reflection?

In its simplest form, reflection is a ‘state of mind’,7 rather than a technique. It prompts us to pause and notice, and then consider the meaning of what we noticed.8 It is a continuous, cyclical process which contributes to self-awareness and professional learning (See Figure 1 below). Reflection encourages staff to consider their impact on others, including clients and colleagues. It assists staff to monitor the wellbeing of others and encourages organisational and collective care of the workforce. It is a bridge between theory and practice and improves decision-making. Problem solving however is not the primary focus, learning is.9

Reflection features:

- active listening, sitting with silence and the discomfort of not always knowing

- a stance of curiosity

- open questions to make sense of situations and to support knowledge for decision-making

- empathy and non-judgement to work through complex issues, emotions and reactions in a safe-enough space

- vulnerability, allowing participants to ease the need to always appear self-reliant and strong

- a critical approach and ‘sitting outside’ our personal experience to notice how the system might be experienced by others.

Figure 1: KOLB reflective learning cycle10

This reflective learning cycle provides the ‘how’ of reflective supervision. The idea is to regularly reflect on all four learning processes (experience, reflection, analysis and action), moving from surface to depth and shifting between them, as required.11 It assists supervisees and supervisors to unpack an experience and better understand it. The goal is to be less reactive, learn from reflection and improve decision-making. The model can be used to process various experiences. These might include conflict with other professionals, case practice with clients and the dynamics experienced in the supervisory relationship.

Questions that accompany the learning cycle processes

Experience questions

- Tell me about the case.

- What happened during the contact?

- What was the purpose of the contact?

- What do we know about the client(s) background, their strengths and supports available?

- What happened when you spoke with (family member/other professional)?

- How would you describe the client’s demeanour?

- What did you notice about yourself during the contact?

- What have other professionals said about the client(s)?

Reflection questions

- What were your feelings towards the client(s) during the contact?

- How would you describe your relationship with the client(s)?

- What is the client’s relationship like with their family, friends and other services?

- Does the client remind you of anybody?

- Describe any differences between this contact and previous contact.

- How do you think the client is feeling at the moment? What is this based on?

- How do you feel after the contact?

- What biases or assumptions about the situation or client(s) might have influenced you?

Analysis questions

- How did you make sense of what the client(s) told you or any changes you have noticed?

- What are the client’s strengths and what resources can they use?

- What are the challenges and risks?

- Did the contact confirm or challenge your previous thoughts about the client(s)’ situation?

- What evidence is there to support this?

- Is there any research that might assist us to think about the implications of the information we have?

- What information is missing?

- What professional development or research do you think might help you with this case?

Action questions

- Given our reflection, what do you think we need to do and why?

- What other options are there?

- What does the client(s) want?

- What do you want to achieve with the client(s)?

- What might the client(s) think about your role and what do they need from you?

- What is urgent versus desirable?

- What support or information do you need to make the next step?

- What information do you need to share with other professionals?

- How do you see your role going forward?

- How do you plan to use your positional power going forward?

- How can I support you?

Four levels of reflection

It can be helpful to consider the following four levels of reflection:11

- Technical reflection compares performance with knowledge of what should have happened. It is useful in addressing accountability and compliance issues.

- Practical reflection relates to the supervisees’ self-evaluation, insight and learning. Reflection on action (after the experience) enhances a practitioner’s ability to do reflection in action. This involves being able to use experience and intuition to respond in the moment.

- Critical reflection acknowledges that understanding is never complete. Understanding is continuously evolving and is influenced by the social and political context. It is an important process to uncover and explore power, assumptions, biases and values at an individual and organisational level. This reflection informs and improves practice, as well as raising the moral and ethical aspects of practice. It is crucial for embedding intersectionality.

- Process reflection explores conscious, unconscious and intuitive aspects of practice even when it is difficult or uncomfortable. It delves into the psychological aspects of the work, exploring client and supervisee histories, motivations, behaviours and reactions. This process can use trauma, attachment and systems theories to explore the complex dynamics and patterns of interacting.

All four levels of reflection are important, depending on the context and type of supervision, such as managerial or clinical supervision. For more on these, refer to the supervision definitions information sheet.

Reflexivity

The sector often uses the term reflexivity, which is like reflection. Simply, reflection leads to insight about something, whereas reflexivity involves finding strategies to question our ‘attitudes, values, assumptions, prejudices, and habitual actions’. Reflexivity helps us understand how we contribute to the dynamic with others.13

Reflexivity extends the reflective learning cycle. It is a deeper process, like critical and process reflection. Reflexivity can prevent generalising client stories and enables supervisees to see what is unique about every case. It involves clarity and awareness of the way practitioners are experienced and perceived by others.

We make sense of situations through stories. Therefore, strategies to enhance reflexivity include journalling about the work and regularly doing through-the-mirror writing.14 This is where practitioners use imaginative stories, drawn from experience, to explore the problems, anguish and the joys of practice. These can be shared and discussed with colleagues and supervisors to increase learning about the self.

'To be reflexive is to examine … how we – seemingly unwittingly – are involved in creating social or professional structures counter to our own values (destructive of diversity, and institutionalising power imbalance, for example). It is becoming aware of the limits of our knowledge, of how our own behaviour plays into organisational practices and why such practices might marginalise groups or exclude individuals.' —Bolton, 2009

Reflection readiness

Reflection is not always a positive and desirable process and both supervisees and supervisors need to be ready to move into reflective practice.15 This is because exploring the more challenging and difficult aspects of practice requires motivation, energy and openness and we can become self-protective. Supervisors need an empathic, non-judgemental approach and to gauge the supervisee’s willingness to explore deep reflection.

Sometimes, there are tensions. Organisations must balance wanting a healthy learning culture that embraces reflective practice and feedback/feedforward, with practitioner reflection readiness.

'It can be difficult to embed reflective practice at first because it involves time and conscious effort but with persistence it becomes natural and habitual.' —Hewson and Carroll, 2016

Safety

It is useful to think of safety along a continuum rather than a binary model of feeling safe or unsafe. Practitioners sometimes point to lack of safety for not engaging in supervision or challenging conversations. This may be more about feeling uncomfortable, which is necessary for growth and learning. The concept of being ‘safe enough’ to be vulnerable and willing to explore the impacts of the work is more useful than using the language of ‘being unsafe’.16 Yet, if after their own reflection a supervisee genuinely feels there is a lack of safety in their supervisory relationship, organisations need to provide a system to hear and review this.

When thinking about safety, it is important to also ensure that organisations and supervisors create an environment that is culturally responsive and safe for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander supervisees and people from other diverse communities.

Trauma and violence-informed approach

This information sheet is supported by an agreed set of trauma informed principles based on the Blue Knot Foundation model. It is recognised that other trauma informed models are equally useful, such as the Sanctuary Model.17

In the family violence context, it can be useful to adopt a trauma and violence informed approach, which expands the concept to ‘account for the intersecting impacts of systemic and interpersonal violence and structural inequities on a person’s life’.18

Trauma and violence-informed principles can be useful in underpinning reflective supervision.19 Especially since many supervisees and supervisors have their own lived experience of trauma, or family or sexual violence and the impacts of inequality, discrimination and marginalisation Talking with practitioners who have not experienced trauma and who may benefit from privilege about the principles and impacts of trauma and violence is equally crucial.

A trauma and violence-informed approach also assists supervisors and supervisees to have explicit conversations about the power dynamics that may impact their relationship.

This approach aligns with the Framework for trauma-informed practice,20 which promotes reflective supervision as a key strategy in creating trauma-informed workplaces.

Table 1: Trauma informed principles in practice adapted from the Blue Knot Practice Guidelines21

| Principle | What this looks like | Reflective Questions |

|---|---|---|

| Safety | Foster physical, psychological, identity and cultural safety in all interactions. | How does your organisation create safety for supervisees and supervisors? How can we create greater safety in our supervisory relationship? How can you create safer relationships with clients, colleagues and other professionals? |

| Trust | Invest in inclusive relationships that focus on mutual respect, dignity and transparent, unbiased communication. | Does your organisation demonstrate trauma sensitivity at all levels of contact? How do you and your organisation convey reliability to the workforce and clients? |

| Choice | Provide freedom for supervisees and supervisors to align their approaches with their values and ethics. | How do you embed discussions about values and ethics during supervision? How does supervision provide choice for your supervisees (and in turn clients) where it is available and appropriate? In what ways? |

| Collaboration | Share power and work in solidarity to support sustainability at a team, organisation, funding body and sector level. | How does your supervision style develop a sense of ‘doing with’ rather than ‘doing to’? |

| Empowerment | Develop individual and collective strengths by acknowledging each other’s contributions and feedback or feedforward for continuous learning and reflection. | Is empowering supervisees and clients an ongoing goal of supervision and your service? How is this goal enabled by supervision, service systems, programs and processes? How does supervision and your organisation enable cultural empowerment? |

| Respect for inclusion and diversity | Develop an awareness that attitudes, systems and structures can interact to create inequality and exclusion. Respect diversity that includes intersecting social characteristics such as but not limited to cultural background, Aboriginality, sexual orientation, gender, gender identity, age, mental health, socioeconomic status, religion and disability. | How does supervision and your service convey and enact respect for workforce and client diversity in all its forms? In what ways? How does supervision and your organisation promote cultural safety? |

Table 1: Trauma-informed principles adapted from the Blue Knot Model

Footnotes

1 D Hewson and M Carroll, Reflective Practice in Supervision, MoshPit Publishing, Hazelbrook, NSW, 2016.

2 Hewson and Carroll, Reflective Practice in Supervision.

3 Department of Human Services, Leading Practice A resource guide for Child Protection leaders, 2nd edition, State of Victoria, 2014, accessed 27 February 2023.

4 Department of Human Services, Leading Practice A resource guide for Child Protection leaders.

5 Hewson and Carroll, Reflective Practice in Supervision.

6 Supervision frequency will be included in the Guidelines as a recommended standard.

7 G Bolton, ‘Reflective practice: an introduction’, in G Bolton and R Delderfield (eds), Reflective practice in writing for professional development, 2nd edn, Sage, London, 2009.

8 Hewson and Carroll, Reflective Practice in Supervision.

9 Hewson and Carroll, Reflective Practice in Supervision.

10 DA Kolb, Experiential Learning: experience as the source of learning and development, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1984.

11 Department of Human Services, Leading Practice A resource guide for Child Protection leaders.

12 G Ruch, ‘Reflective practice in contemporary child-care social work: the role of containment’, The British Journal of Social Work, 2007, 37(4): 659-680, doi:10.1093/bjsw/bch277.

13 Bolton, ‘Reflective practice: an introduction’.

14 Bolton, ‘Reflective practice: an introduction’.

15 Hewson and Carroll, Reflective Practice in Supervision.

16 V Reynolds and M McQuaid, ‘Do You Have A Culture Of Collective Accountability?’, Making Positive Psychology Work podcast, 2021.

17 Sanctuary Institute, Sanctuary Model, Sanctuary Institute website, 2023, accessed 17 August 2023.

18 Varcoe CM, Wathen CN, Ford-Gilboe M, Smye V and Browne, VEGA briefing note on trauma- and violence-informed care, VEGA Project and PreVail Research Network, Ottawa, 2016 p. 1, in Family Safety Victoria, MARAM practice guides: Foundation knowledge guide, Victoria Government website, p. 43.

19 Blue Knot, Trauma-informed services, Blue Knot website, 2019, accessed 1 March 2023.

20 Department of Families, Fairness and Housing (DFFH), Framework for trauma-informed practice, DFFH website, 2022, accessed 27 February 2023.

21 Blue Knot, Practice Guidelines, Blue Knot website, 2012, accessed 20 July 2023.