Consistent and collaborative practice supports victim survivors to receive an appropriate response wherever they choose to access support. Consistent practice is achieved through work undertaken to develop (as WoVG lead) and embed (as portfolio and sector leads) MARAM policy into operational practice.

A consistent approach across the service system enables the development of collaborative practice– different sectors understand the best response to family violence and work together to achieve MARAM outcomes. To help achieve consistency, FSV creates centralised resources that are shared with departments and sectors, who then tailor and embed the resources into their workforces. To ensure that this consistency is maintained, FSV works closely with departments and sectors when they are tailoring the resources.

The Royal Commission identified that information sharing between services is essential for keeping a victim survivor safe and a perpetrator in view and accountable as part of collaborative practice. This is highlighted throughout this section. Information sharing is an organisational requirement under MARAM responsibility 6.

Section A: Family Safety Victoria as WoVG lead

Highlights

- Adult perpetrator-focused MARAM Practice Guides and tools were developed throughout 2020-21 in partnership with No to Violence and Curtin University, with consultations with more than 1,000 professionals.

- Use of online MARAM tools through all available platforms significantly increased in the reporting period, including a 72 per cent increase in risk assessments undertaken by The Orange Door using TRAM.

- Ongoing implementation of the Central Information Point (CIP), and expanding access to the CIP to Risk Assessment and Management Panels (RAMPs).

Perpetrator-focused MARAM Practice Guides

Adult perpetrator-focused MARAM Practice Guides and tools were developed throughout 2020-21 in partnership with No to Violence and Curtin University. They draw upon a range of evidence and best practice models available across Australia and internationally to support direct intervention with perpetrators of family violence, including Tilting our practice,[18] Caring dads,[19] invitational narrative approaches,[20] transtheoretical model of change,[21] and various cross-jurisdictional reviews of perpetrator typologies.

The scope of the Practice Guides’ responsibilities also reflects the Everybody Matters statement and evidence provided by the Expert Advisory Committee on Perpetrator Interventions (EACPI) Report and the Centre for Innovative Justice’s mapping of roles across key workforces.[22]

FSV conducted a series of consultations throughout 2020-21 with more than 1,000 professionals, including specialist practitioners working with people using violence against Aboriginal communities, LGBTIQA+ communities, culturally, linguistically and faith diverse communities, older people and people with disabilities, academics, sector leaders and government departments.

The new perpetrator-focused resources support professionals to understand their responsibility for risk identification, assessment and management. They create new approaches to individual, service and system-level perpetrator accountability through better coordination of interventions across services as reflected in MARAM principle 9. The new resources also maintain a focus on victim survivors by recognising their experiences and the impacts of violence and coercive control while supporting interventions with perpetrators that reinforce victim survivors’ safety.

The perpetrator-focused resources are scheduled for release during 2021-22 with tailored training to follow.

Information Sharing Resources and Tools

Amendments to the FVISS Ministerial Guidelines were made on 19 April 2021 as part of the rollout of Phase 2. These amendments addressed the introduction of new entities into the FVISS under Phase 2 and provided further clarity regarding the operation of the FVISS in response to common questions received from ISEs. The guidelines are legally binding and apply to all ISEs.

The Central Information Point (CIP)

As the family violence system matures and the reforms improve family violence literacy across new and emerging workforces, there is increased capacity to identify the risk that perpetrators of family violence pose to family members and for the system to intervene to keep victim-survivors safe.

The CIP provides consolidated, risk-relevant information in one report to support frontline practitioners to assess and manage family violence risk. The CIP is currently available to The Orange Door Network, selected RAMPs and Berry Street Family Violence Services Northern Region. It brings together information about perpetrators of family violence from Victoria Police, Court Services Victoria, Corrections Victoria and Child Protection. The CIP aligns with MARAM Responsibility 6 (contribute to information sharing), Responsibility 9 (contribute to coordinated risk management) and Responsibility 10 (collaborate for ongoing risk assessment and risk management).

In addition to supporting more informed risk assessment and safety planning for women and children, the CIP is fundamental to the uplift in system capacity to keep perpetrators in view and ensure they are held accountable and risk management interventions are appropriately targeted. This is particularly important as the reforms are at a point where the system is increasingly shifting its focus to addressing perpetrators as the source of family violence, and to building a web of accountability around them. This is a key focus for the Family Violence Rolling Action Plan 2020-2023, which outlines the WoVG program of work under the Strengthening perpetrator accountability for family violence plan.

In addition to being integrated into the practice and operations of The Orange Door Network, the CIP is underpinned by FVISS, under the Family Violence Protection Act 2008. The CIP is also embedded within and is an enabler of a shared and consistent approach to identifying and managing family violence risk and supporting multi-agency risk assessment and management, in accordance with MARAM. The CIP provides a risk assessment and management tool that can be used in shifting attention away from the behaviours and actions of victim survivors to instead focus on stopping perpetrators from using violence and holding them accountable for their actions.

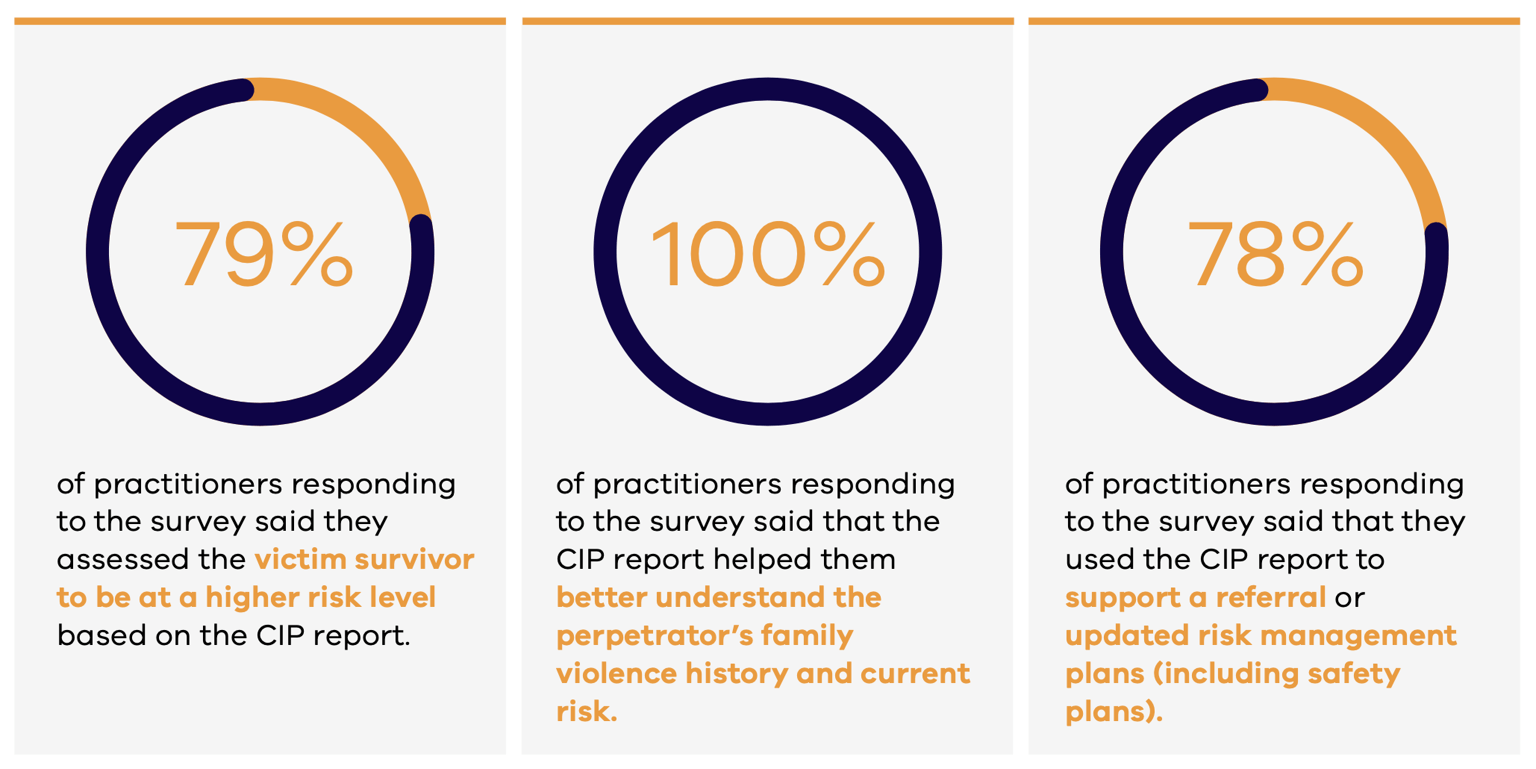

In June and July 2021, a survey was conducted with The Orange Door on the practice impacts of the CIP. FSV received 57 responses, from a mixture of roles across The Orange Door. This survey found the following:

In October 2020, the CIP was made available to the first set of RAMP areas as part of a phased rollout in response to a Royal Commission recommendation.[23]. The following RAMP areas have received training and guidance and now have access to the CIP:

- Western Melbourne

- Brimbank Melton

- Hume Moreland

- Outer Eastern Melbourne

- Ovens Murray.

CIP Case Study 1:

A RAMP coordinator was asked to case consult by a specialist family violence service. The victim survivor and perpetrator had a baby girl together. The perpetrator was engaged with The Orange Door due to family violence and other offences, and it was noted that the perpetrator was requesting to have regular contact with the baby. The RAMP coordinator submitted a CIP request to determine if this contact could take place safely. The CIP report showed a timeline of offences involving the perpetrator’s child from a previous relationship, as well as offences involving young people not related to him. The CIP report also demonstrated there had been limited system accountability around his use of family violence with past victim survivors and the harm caused to very young girls through sexual exploitation. As a result of information disclosed in the CIP report, agencies were able to advocate for support and conditions to be put in place for safe contact to take place.

CIP Case Study 2:

After a referral from Child Protection, the victim survivor, Teri, attended a specialist family violence service (SFVS) for an intake assessment. Teri had never reported or discussed the violence due to serious threats to her and her child’s life. She was also very frightened of the likely repercussions from the perpetrator if she reported the violence. Teri had also faced barriers to service engagement which affected her decision regarding how much information she was comfortable sharing with the service. Over a number of sessions Teri provided information regarding the serious and often life-threatening violence (including multiple strangulations). The SFVS determined there was a high risk and had concerns for the safety of both Teri and her young son. A referral to RAMP was made and due to significant gaps in the risk assessment and limited information regarding the perpetrator, a CIP report was requested.

From the CIP report, the RAMP co-ordinator learned that the perpetrator had a significant criminal history, including the use of weapons (hidden at the home) in previous family violence incidents. The RAMP coordinator also learned the perpetrator was a recidivist family violence offender who had used very serious violence against a number of intimate partners. This perpetrator also used high levels of violence in the community. Due to this information, RAMPs were able to determine a pattern and history of violence and a timeline of the family violence offending. This case was then accepted for a RAMP response where an appropriate risk management and safety plan was developed and implemented including for the management of the perpetrator.

Tools for Risk Assessment and Management (TRAM)

TRAM is used by practitioners in The Orange Door and a select number of specialist family violence agencies for risk assessment.

During 2020-21, 11,751 risk assessments were undertaken by The Orange Door practitioners using TRAM. This represented a 72 per cent increase on the previous year. This increase has been particularly strong for Child Risk Assessments with a rise of over 150 per cent over the last year.

This increase is driven by the increased caseload; however, there was also an increase in the proportion of cases that had a TRAM risk assessment, with 18 per cent of referrals received by The Orange Door having a TRAM risk assessment in 2020-21, up from 13 per cent in 2019-20 and 12 per cent in 2018-19.

Table 3: Number of MARAM risk assessments and safety plans undertaken by The Orange Door since commencement (using TRAM and the CRM)

| 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Adult Comprehensive Risk Assessment |

4,417 |

5,879 |

9,343 |

19,639 |

|

Child Risk Assessment |

942 |

958 |

2,408 |

4,308 |

|

Safety Plan |

3,399 |

6,123 |

8,797 |

18,319 |

|

Total |

8,758 |

12,960 |

20,548 |

42,266 |

Specialist Homelessness Information Platform and Service Record System (SHIP)

SHIP is used by homelessness services and some specialist family violence services.

The MARAM tools in SHIP were first implemented in late August 2020. Over the period August 2020 to June 2021, 27,333 MARAM risk assessments and 6,061 MARAM safety plans were undertaken in SHIP. This amounts to over 33,000 MARAM risk assessments and safety plans undertaken by 237 different agencies over this period.

Table 4: Number of MARAM risk assessments and safety plans undertaken in SHIP since implementation

| 2020-21 | |

|---|---|

|

Screening tool |

529 |

|

Brief risk assessment |

1,161 |

|

Intermediate risk assessment |

899 |

|

Comprehensive risk assessment |

16,993 |

|

Child risk assessment |

7,751 |

|

Basic safety plan |

1,051 |

|

Intermediate safety plan |

407 |

|

Comprehensive safety plan |

3,907 |

|

Other safety plan |

696 |

|

Total |

33,394 |

In addition to online versions of the tools, many organisations are using their own adapted versions of the MARAM tools in paper or non-case management system format. Reflections on these tools from a VACCA practitioner show the benefits to practice:

Practitioner reflections from the Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency (VACCA)

The new MARAM tools provide a holistic framework to assist with identifying current risk as well as any historical intergenerational trauma to allow practitioners to design healing plans that respond to a family’s whole experience of family violence.

In terms of the Risk Assessment tool, practitioners have reflected that it is useful therapeutically in opening up conversations about and understandings of, family violence. A key aspect of this is how the tool supports the practitioner to continue to hear what the client is bringing and not to make a binary and/or essentialising judgement at the outset about who may be using or experiencing harm. Rather than being used all at once, practitioners find that it works best when used over a series of sessions and when revisited to reflect on shifts that have taken place around dynamic risk and safety.

Intersectionality Capability Framework and Tools

Improved understanding of structural inequality and discrimination is necessary for a robust understanding and implementation of Principle 3 of MARAM.

Embedding inclusion and equity: an intersectionality framework in practice was developed by FSV to support organisations to build capability in understanding and applying an intersectionality framework within their existing practice.

Resources developed to support embedding an intersectional approach include:

- Essential knowledge for all - an introduction to intersectionality including in the Australian context, the importance of an intersectionality framework and intersectionality in practice

- tip sheets for managers, leaders, supervisors and executive/boards - guidance to lead on aligning policies and procedures with an intersectional approach

- tip sheets for all - guidance on critical reflection, embedding lived experience in service delivery, respectful and safe engagement of people with lived experience, supporting a diverse workforce, partnerships for inclusion and facilitating response pathways

- tools for ongoing support - including an organisational self-assessment and auditing and monitoring tool, an inclusive language guide, a safe and respectful conversations guide and a critical reflection tool.

The framework and tools will be user tested during 2021-22 before wider release.

Section B: Departments as portfolio leads

Highlights

- FSV partnered with DV Vic to develop case management program requirements for Family Violence Services and Family Violence Accommodation Services.

- Chief Psychiatrist guidelines were updated to incorporate the family violence Brief and Intermediate risk assessments within routine mental health assessments to support a MARAM-aligned response.

- The courts introduced digital versions of the risk assessment, safety planning and risk management tools for adult victim survivors for use by family violence practitioners at the Magistrates’ Court of Victoria and the Children’s Court of Victoria to support consistent practice and data capture.

- In 2020-21, the Alcohol and Other Drug (AOD) Statewide Intake and Comprehensive Assessment tools and accompanying clinician guidelines, were updated to incorporate the MARAM victim survivor framework and tools. These tools and guidelines are used state-wide to support consistent intake and assessment of clients accessing AOD treatment across Victoria.

- Victoria Police delivered a new record-keeping solution for the FVISS/CISS to improve data capture, workflow processes and the output shared with other ISEs.

- Victoria Police shared a total of 5,368 information sharing requests through FVISS and CISS.

- Courts received 28,266 FVISS requests in 2020-21, an increase of more than 30 per cent since 2019-20. The courts introduced updated FVISS and CISS request email templates for family violence practitioners to streamline request processes and support a consistent approach to information sharing.

- DJCS Victims of Crime (VOC) helpline now has statewide search access, improving risk assessments.

DFFH: Child Protection

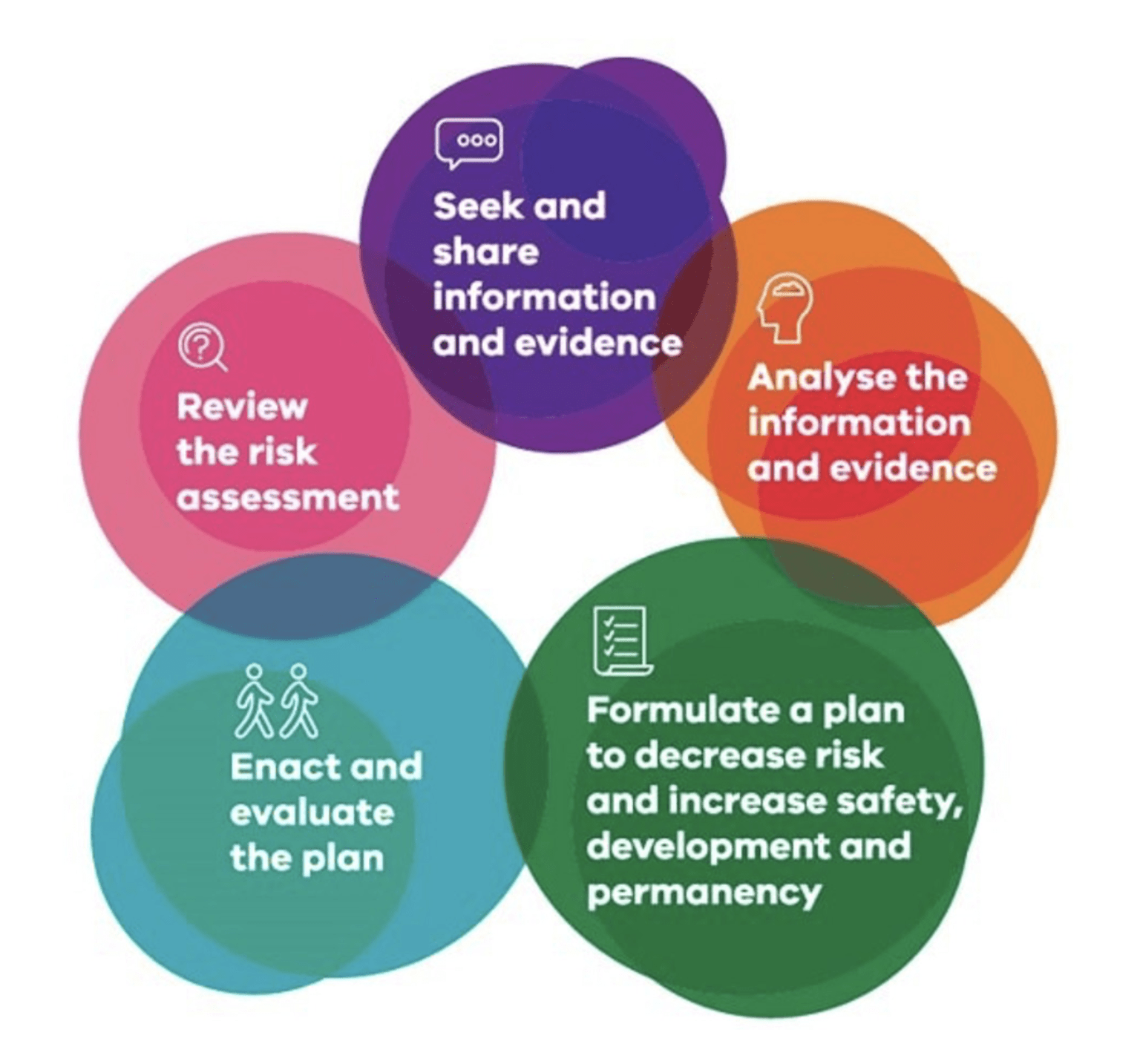

SAFER is a guided professional judgement approach to risk assessment and practice for child protection practitioners. The framework integrates MARAM risk assessments and risk management and draws upon the Best Interests Case Practice Model. SAFER is represented by five key practice activities for child protection practitioners:

- Seek and share information

- Analyse the information gathered to determine risk of harm

- Formulate a plan of action to address those risks and the child’s needs

- Enact the plan and

- Review changes and reassess the risks.

The Child Protection Manual was updated to incorporate a specific family violence resource page including the MARAM responsibilities and family violence risk assessment and management tools. As a result, Child Protection Practitioners can now access MARAM-aligned assessment tools to support the identification and assessment of family violence risk to victim survivors.

DH: Ambulance Victoria

Ambulance Victoria is progressively identifying those aspects of MARAM relating to collaboration, that can be embedded into existing Ambulance Victoria tools, systems and processes. In relation to information sharing and collaboration, Ambulance Victoria has updated its stakeholder mapping tool to identify local and national partners to support information sharing, secondary consultations and referrals including stakeholders who can support a culturally safe approach for Aboriginal people and a tailored approach for other priority groups. Ambulance Victoria also actively participates in state-wide inter-agency and network meetings, community networks and communities of practice in which family violence risk assessment and management is a focus. In relation to recognising children as victim survivors, a separate electronic care record is created for children, and the Statement of Commitment to Child Safety strengthens the Child Safety Code of Conduct to improve empowerment and participation when working with children and young people.

DH: Alcohol and Other Drugs

In 2020-21 Turning Point was commissioned by the Department of Health and Human Services (as it then was) to review and update the AOD Intake and Comprehensive Assessment tools and accompanying clinician guidelines, to incorporate the MARAM victim survivor framework and tools. These tools and guidelines are used state-wide to support consistent intake and assessment of clients accessing AOD treatment across Victoria.

Turning Point established a collaborative working group with government and the AOD peak body VAADA to analyse how the MARAM victim survivor framework and tools could be incorporated into AOD intake and assessment practice.

The group met regularly to draft changes to the tools and guidelines and consider the impact on the AOD workforce and AOD clients experiencing family violence. Turning Point consulted regularly with a larger group of AOD managers and practitioners to discuss the proposed changes and seek their feedback. Turning Point also consulted with AOD consumers and sought their feedback regarding the proposed changes. Expert family violence advice and sector knowledge was provided by AOD Specialist Family Violence Advisors (SFVA) and VAADA.

The amendments were endorsed, and the new documents were published in April 2021. The updated documents now include MARAM family violence screening questions embedded in the state-wide tools, and a MARAM-aligned safety plan has also been embedded in the Comprehensive Assessment tool. The clinician guidelines provide comprehensive MARAM information tailored to the AOD workforce, an explanation of the changes, and expectations and support for the AOD workforce to align their practice with MARAM.

DJCS: Youth Justice

Over the past year, agencies funded by Youth Justice reported new and continued membership and active participation within family violence community of practices, multi-agency workshops and care teams. This includes membership and engagement with the quarterly FSV and Orange Door lead Family Violence community of practice. Several agencies have established information sharing MOUs with their local family violence support services, improving their processes towards better collaborative responses to family violence participants.

Youth Justice funded agencies reported continued use of MARAM identification, screening, risk assessments and safety planning tools. Examples of maintaining alignment include the following:

- Ballarat Community Health (BCH) employed a MARAM project officer to ensure consistency of MARAM alignment across the different program areas, including monitoring FVISS and the CISS information requests and practices. In addition to this, BCH’s client services program managers formed a working group to ensure MARAM Practice Guides, frameworks, resources, tools and policies continue to be embedded into BCH’s policies and practices.

- Quantum created a digital resource to support their practitioners to understand and implement family violence safety planning in collaboration with La Trobe Health Assembly. This resource was then shared broadly with MARAM-prescribed agencies across the Gippsland region. This resource was developed in response to an identified need for a more interactive training product that could be delivered virtually during the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions.

DJCS: Consumer Affairs Victoria Funded Agencies

All external organisations that deliver Financial Counselling Program (FCP) and Tenancy Assistance and Advocacy Program (TAAP) regularly participate in activities that promote collaborative practice, both internally and externally, including with specialist family violence services and others with responsibilities for comprehensive risk assessment and management.

Many organisations reported strengthened relationships with their local The Orange Door Network and family violence services, with secondary consultations working both ways - specialists know who to contact about economic abuse and tenancy problems, and FCP and TAAP workers can get family violence support for better client outcomes.

’I feel that our organisation has open and collaborative discussions across multiple teams when assessing clients who disclose experiencing family violence. This collaboration continues to build our knowledge on assessing risk and responding consistently and effectively to clients’ (Consumer Action Law Centre financial counsellor).

Consumer Affairs Victoria will develop an information sharing practice kit that includes fact sheets of information held by FCP and TAAP to be used for creating better cross-sectoral understanding of what risk relevant information is available.

TAAP case study:

A TAAP client was seeking to be released from her lease and excused from being held financially responsible for damages to the property that had been caused by a violent ex-partner. Evidence of these damages, held by Victoria Police, was required for the VCAT hearing. Previously the TAAP worker would need to apply under Freedom of Information, which would delay the hearing. Requesting the information using the FVISS enabled the TAAP worker access to the required evidence from Victoria Police in a timely manner, allowing the victim survivor to have a successful outcome at VCAT and escape from the economic abuse.

DJCS: Corrections Victoria

DJCS has collaborated with FSV and DPC to support the building of a new workplace application for the CIP. The workspace application will allow Corrections Victoria’s Central Information Point staff to efficiently share information under the FVISS and contribute to the safety and protection of those experiencing family violence by bringing perpetrators into view.

The project is on track and the new application was launched in June 2021. Further work will occur to consider additional IT changes outside of the original scope that has been requested by FSV.

Corrections Victoria responded to a total of 2047 information sharing requests in 2020-21. The introduction of Phase 2 of the information sharing and MARAM reforms on 19 April 2021 is one of the reasons for an increased trend in information requests towards the end of 2020-21.

Table 6: Number of family violence risk information requests under the FVISS received by Corrections Victoria in 2020-21

| Month | No. of Requests responded to | No. of requests not released* |

|---|---|---|

|

July 2020 |

157 |

11 |

|

August 2020 |

138 |

6 |

|

September 2020 |

165 |

0 |

|

October 2020 |

188 |

2 |

|

November 2020 |

165 |

1 |

|

December 2020 |

161 |

2 |

|

January 2021 |

121 |

0 |

|

February 2021 |

161 |

7 |

|

March 2021 |

180 |

4 |

|

April 2021 |

163 |

12 |

|

May 2021 |

213 |

22 |

|

June 2021 |

235 |

26 |

|

TOTAL |

2047 |

93 |

*Common reasons why information was declined in some instances: where the identity of the perpetrator could not be confirmed based on the initial information provided; further information was required for protection purposes; exclusion; no consent; or the entity requesting the information was not an Information Sharing Entity (ISE).

FSV: The Orange Door

Collaborative practice: Every The Orange Door has a Service System Navigator to support the development of referral pathways to improve client outcomes. Every The Orange Door has developed or is in the process of developing ‘in reach’ agreements with area-based legal services, financial counselling services, housing services, mental health services and AOD services to the responses for people impacted by family violence. There are service interface agreements with inTouch Multicultural Centre Against Family Violence, Men’s Referral Service, Victims Support Agency, Child Protection and Integrated Family Services, Djirra and the Magistrate’s Court of Victoria.

Consistent practice: There is a state-wide approach across The Orange Door to assessing family violence risk including the use of a statewide priority tool that includes the evidence-based family violence risk factors and application of structured professional judgement to assist in determining priority of response to all referrals to The Orange Door.

FSV: After-Hours Crisis Response

FSV has undertaken significant work to deliver a consistent and secure referral process for local after-hours crisis response services through the integration of referrals to SHIP. With Safe Steps, FSV trialled sending all confidential information (including the MARAM assessment, client consent and relevant case notes) to an after-hours crisis response service provider through the SHIP platform.

This project delivered significant improvements in relation to data capture, which enable visibility of real-time data at an area and state-wide level, overcame previous data integrity issues and provided significant efficiency gains for services. Previously referred to as a specialist family violence service model, the case management program requirements will guide services in the delivery of consistent, coordinated, timely and flexible case management support to victim survivors responding to their safety and support needs. The case management program requirements will include foundational elements of a new 24/7 Crisis Response Model, which includes a concept of shared responsibility for crisis responses across the whole specialist family violence service system.

Pitched at the agency level, the case management program requirements will articulate different initiatives and resources that are either legislated or embedded as key system enablers to provide safe, consistent and high-quality responses to victim survivors, including children. This includes MARAM, the Code of Practice: Principles and Standards for Specialist Family Violence Services for Victim Survivors and the FVISS and CISS.

The Courts

The number of FVISS requests received by the courts has continued to grow. The courts received 28,266 FVISS requests in 2020-21, an increase of more than 30 per cent since 2019-20.

This included 14,421 (51 per cent) requests from the DFFH Child Protection and 5,475 (19 per cent) requests from The Orange Door Network. The remaining 30 per cent of FVISS requests came from specialist family violence service providers including Safe Steps and community-based organisations.

Table 5: Information sharing requests for 20-21 financial year

| Type of activity | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Total financial year | Total since February 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Requests |

6,872 |

6,794 |

7,100 |

7,500 |

28,266 |

57,604 |

|

Voluntary |

6,788 |

6,709 |

7,007 |

FVISS: 7,293 CISS: 42 * FVISS/CISS: 6 |

27,845 |

*Note that the Courts were prescribed to the Child Information Sharing Scheme as part of Phase 2 from 19 April 2021

The Magistrates’ Court Central Information Sharing Team Case Study:

The court’s central information sharing team received an urgent FVISS request from The Orange Door for risk assessment.

The Orange Door were completing a risk assessment with a victim survivor and requested information about the currency of a Family Violence Intervention Order (FVIO) as the victim survivor reported that the FVIO had been revoked.

The information sharing team confirmed that a current final FVIO was in place but that the victim survivor had applied to revoke the FVIO, which was listed to be heard in two weeks’ time.

The information sharing team reviewed the original police application for the FVIO and identified multiple evidence-based risk factors including physical assault and threats to kill that had occurred in front of children.

This prompted further review of relevant risk information held by the Magistrates’ Court of Victoria (MCV) which identified that the respondent was currently remanded for committing criminal family violence related matters.

Under the FVISS, the information sharing team shared the following information with The Orange Door Network:

- that there was a current final FVIO in place

- that the respondent was currently remanded in custody

- details of the next criminal listing date.

The Orange Door completed the risk assessment and developed a risk management and safety plan with the victim survivor based on a more complete picture of all relevant information.

Victoria Police

Victoria Police has continued to engage closely with other Information Sharing Entities (ISEs) by improving the FVISS and CISS information request form and process. This ensures that the information request process is more intuitive for ISEs, the correct information is released and ISEs are aware of information security requirements for law enforcement information.

Table 7: Number of FVISS and CISS information sharing requests received by Victoria Police in 2020-21

| Type of activity | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Total financial year | Total implementation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Requests |

1531 |

1122 |

1241 |

1474 |

5,368 |

12,428 |

|

Not shared[24] |

2 |

3 |

10 |

15 |

30 |

35 since the recordkeeping solution was introduced. |

Victoria Police leads by example under FVISS and CISS by developing clear and intuitive information-sharing processes and sharing its guidance with other agencies to encourage consistency across the broader service system. Internally, Victoria Police continues to encourage information sharing under FVISS and CISS through continuing to review policies and practices to ensure they are embedded across the organisation and the release of information is consistent with the intent of the information schemes.

Section C: Sectors as lead – case studies

Ngarra Jarranounith Place case study:

Ngarra Jarranounith Place program, as part of Dardi Munwurro, helps address Aboriginal male offending. It is an intensive residential diversion program for perpetrators of family violence. The case study from Ngarra Jarranounith Place highlights how knowledge of MARAM and the FVISS are already being used to respond to perpetrators in practice:

A man in his late 30s was participating in a ReLink program, which prepares people to successfully reintegrate into their communities. Earlier reintegration assessments did not indicate that the man had any history of Family Violence Intervention Orders (FVIOs). However, while in conversation with the ReLink Reintegration Coordinator, the participant disclosed that he had been named on a FVIO as a respondent.

The man’s account was that the police had initiated the order, that the protected person did not want the order in place, the violence was of a minimal to moderate level and that the family violence order had expired.

The coordinator made a FVISS request from the courts. It became clear that the man had substantially denied and minimised the seriousness and severity of his perpetrating and he had an FVIO in place against him until further order (no expiry date). The advice provided included that the police have serious concerns for the safety of the women and children victim survivors when the man is released from custody.

With this information, as well as a range of other details relating to the participant’s most recent offending, the coordinator worked with the participant to develop a transition plan that addressed and managed the risk of any ongoing use of violence against the women and children.

Strengthening Hospital Responses to Family Violence SHRFV Antenatal Implementation

The Royal Commission into Family Violence recommended that routine screening for family violence should be in place in all public antenatal settings and the screening guidance should be aligned to MARAM (recommendation 96). The department partnered with the Strengthening Hospital Responses to Family Violence (SHRFV) initiative to establish a project to support antenatal services implement routine screening for family violence during pregnancy. New MARAM-aligned guidance, case studies and a specialist supplementary e-learn module for public antenatal settings was developed as part of the project, with a series of webinars in 2020. A dedicated information session for the Koori Maternity Services workforce was also facilitated in partnership with the Victorian Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (VACCHO) and the Maternity Services Education Program.

The department supported the update of the Birthing Outcomes System (BOS), the pregnancy and birth record system used by all by two of Victoria’s public maternity services. BOS was updated to include the MARAM Screening and Identification assessment tool questions. This update supports maternity service providers to screen and provide support to victim survivors in accordance with MARAM.

Public antenatal settings have included the e-learn training and the practice guidance into standard operating procedures and policies. This means that front-line staff complete family violence training, staff feel confident to identify and respond to family violence risk as a standard part of their role.

Summary of progress

The 2019-20 report noted there was a significant focus on the development of resources and updating of policies, procedures, practice guidance and tools.

This report for 2020-21 is demonstrating the shift to embedding responsibilities in practice. There is a marked increase in the use of online risk assessment tools, of information sharing and deepening of collaborative practice demonstrated through the case studies. While many of the examples refer to information sharing, this can be seen to be the enabler of MARAM practice with the case studies and descriptions provided detailing how the shared information is informing the understanding of risk and being used for safety planning.

As Phase 1 organisations become fully operational in their use of MARAM (including in perpetrator response) and as Phase 2 organisations continue the journey of preparation for change and embedding, it is anticipated that the system of consistent and collaborative practice will continue to grow in breadth and complexity.

[18] Kertesz M, Humphreys C and Connolly M 2018, Tilting our practice: a theoretical model for family violence in child protection practice.

[19] Scott K, Kelly T, Cooks C and Francis K 2018, Caring dads: helping fathers value their children (3rd edition).

[20] Wendt S et al. 2019, Engaging men who use violence: invitational narrative approaches (Research report) ANROWS.

[21] Prochaska JO and DiClemente CC 2005, ‘The transtheoretical approach’, in Norcross JC and Goldfried MR (eds.), Oxford series in clinical psychology: Handbook of psychotherapy integration, Oxford University Press, pp. 147-171.

[22] RMIT Centre for Innovative Justice 2018, Bringing pathways towards accountability together: perpetrator journeys and system roles and responsibilities.

[23] A RAMP is a formally convened meeting, held at a local level, of nine key agencies and organisations that contribute to the safety of women and children experiencing serious and imminent threat from family violence. Across Victoria, there are 18 RAMPs that each meet once a month to share information and take action to keep women and children at the highest risk from family violence safe.

[24] Legislative threshold not met.

Updated