Successful implementation of reforms requires mechanisms to learn lessons and apply necessary changes to approach. The 2019-20 report referred to an early evaluation of the implementation of the MARAM reforms and the Monash University review of FVISS.

Those recommendations continue to inform current and future implementation activities. Additionally, as lead for the reforms, FSV actively engaged in multiple governance groups and stakeholder forums to engage sector feedback more directly.

This chapter provides an update on implementation of recommendations by FSV and work to reinforce good practice and commit to continuous improvement.

Cube Group MARAM review 2020

The 2019-20 report contained a summary of the 35 recommendations made by the Cube Group on the early implementation of MARAM. This report contains an update on the progress of responding to those recommendations to improve implementation efforts overall, as well as references to related evaluations and other policies and processes to reinforce good practice and commit to continuous improvement.

FSV has acquitted the following recommendations in the 2020-21 period:

| Recommendation | Action undertaken |

|---|---|

|

2.2: The WoVG governance structures should impose greater scrutiny on status reporting and a clearer process for managing delays. This should include clearly identifying sequencing and dependency issues when delays are anticipated and then clearly specifying the dependencies and non-dependencies (especially work that can continue in parallel to the anticipated deliverables). 3.1: The WoVG governance structure should consider whether separate governance is more fit-for-purpose for the future rollout of CISS and MARAM. 3.2 WoVG delivery arrangements should be ‘reset’ to reaffirm the current division of roles and responsibilities. |

Governance arrangements have been refreshed and strengthened and now comprise a regular WoVG MARAM and Industry Plan Directors Working Group with a clear focus on more streamlined reporting, managing delays, risks and issues. MARAM and CISS governance were separated, but with strong links maintained. A refresh of the roles and responsibilities has been endorsed by the MARAM and Industry Plan Director’s Group. |

|

5.3 FSV should prioritise the completion of the Organisational Embedding Guide and provide clear, published guidance on what alignment with MARAM requires. Consideration should be given to providing stronger expectations of what responsibilities organisations have and how their policies, practice guidance and tools should deliver on those responsibilities (including the potential for minimum standards or requirements). |

FSV released the Organisational Embedding Guide in mid-2020. It is publicly available at: https://www.vic.gov.au/maram-practice-guides-and-resources(opens in a new window). The introduction of minimum standards was proposed by the Royal Commission, but the government determined it was not feasible to introduce such standards at the inception of the framework due to the wide variety of sectors and operating contexts. The MARAM Maturity Model currently in progress will strengthen the monitoring and accountability for each workforce in moving towards alignment. |

|

6.8 FSV should consider how it can support or complement ‘Leading Alignment’ training to improve organisational leaders’ understanding of their organisation’s awareness, the implications, challenges and complexities of alignment and familiarity with MARAM. |

Leading alignment training has been updated to include references to the Organisational Embedding Guide to support understanding for leaders. Resources continue to be identified and developed to support leaders in their understanding of MARAM and awareness of the implications, challenges and complexities of alignment. FSV will continue to work with departments on supporting their leadership, including attending forums and leadership events. |

FSV continues to review and respond to all outstanding Cube Group recommendations including identifying any requirements for a WoVG approach.

Monash FVISS Review 2020

The FVPA requires that an independent review of the operation of the scheme be undertaken two years after commencement of the FVISS and tabled in Parliament. An independent review was undertaken by a team of researchers from Monash University in 2020.

The recommendations of the Monash review aimed to improve the operation of the FVISS and the implementation to Phase 2 organisations. FSV has acquitted the following recommendations in the 2020-21 financial year:

| Recommendation | Action undertaken |

|---|---|

|

11: All training and training materials need to emphasise the circumstances in which it is appropriate to use either the FVISS or the CISS, and that both schemes have the same consent requirements. In particular, the Ministerial Guidelines on this issue should be highlighted and practical exercises and case studies developed that focus on this aspect. |

The FVISS and CISS Ministerial Guidelines, resources and training provide that consent is not required from any person in relation to risk to a child under both schemes, but that a child should be consulted where safe, appropriate and reasonable to do so. Further, the FVISS Ministerial Guidelines provide case studies and advice on preserving the agency of children and adult victim survivors in this context. This approach has been further emphasised by joint online training modules for the schemes. The CISS Ministerial Guidelines include a chapter on the interaction of the schemes, which is cross-referenced in the FVISS Ministerial Guidelines. |

|

13: Consideration should be given to extending the operating hours of the telephone aspect of the Enquiry Line to business hours. Where there is the need for expert legal advice, an appropriate referral to obtain such advice should be provided to the enquiring organisation, where that organisation does not otherwise have ready access to such advice. The Enquiry Line should be fully resourced for at least two years after the prescription of Phase 2 organisations. |

Resourcing to support the continuation of the Information Sharing and MARAM Enquiry Line was provided as part of the Victorian State Budget 2021-22. For the commencement of Phase 2, up to 10 additional staff were trained and on standby to take calls. |

|

14: The online list of ISEs should be completed and made available to all ISEs prior to the prescription of Phase 2. |

A new database of ISEs and RAEs prescribed under the FVISS and CISS was completed in May 2020. The database is accessible online for all ISEs and contains a list of organisations prescribed. |

|

21: Prior to Phase 2, FSV should develop specific practice guidance on and templates for family violence data security standards. These should reinforce existing legislative privacy obligations and create clear expectations on data security standards for family violence information and information sharing. These standards and associated processes should form part of the induction of Phase 2 organisations into the FVISS. Measures should be put in place to ensure these standards are transparent for victim/survivors. |

The FVISS Ministerial Guidelines make clear that the reforms do not replace or override existing laws and standards in relation to data security and that organisations must continue to comply with any requirements that already apply to their organisation. While FSV has noted that it does not have the responsibility to establish new data security standards, Victorian government agencies have been encouraged to develop, where appropriate, tailored advice for prescribed organisations and services in the lead up to Phase 2. |

|

22: The Victorian Government should work with the Mental Health Tribunal to ensure that victim survivor safety is prioritised as part of its processes and to avoid the risk of any adverse consequences arising from the scheme. In particular it should communicate with the Mental Health Tribunal about the family violence risks associated with disclosing to perpetrators/applicants any part of their file that indicates that family violence risk information has been shared without their knowledge under the scheme. |

FSV consulted with the Mental Health Tribunal to ensure that victim survivor safety is adequately considered as part of its processes and to avoid the risk of any adverse consequences arising from interactions with the FVISS. |

FSV continues to review and respond to all outstanding Monash recommendations, including identifying any requirements for a WoVG approach.

2020 Report of the Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor

In May 2021, the 2020 Report of the Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor was released, reporting on the status of reform implementation as at November 2020.[26] The report includes significant discussion on the benefits of MARAM and highlights that it has been instrumental in supporting the transformation of practice within public sector agencies since the Royal Commission into Family Violence.

The report identifies areas for improvement:

- more robust central coordination of MARAM

- funding to support implementation of MARAM and information sharing in health, mental health and education settings

- continued investment in capacity-building activities to support application of MARAM and the information sharing schemes to children

- new training and support to universal and justice workforces to understand and operationalise the MARAM perpetrator practice guides

- continued delivery of new online training and ongoing effort to improve the reforms based on feedback and evaluation findings.

FSV is addressing these areas for improvement, with many of them to be supported through the State Budget 2021-22 investment in further MARAM and information sharing implementation.

MARAM Annual Survey of Organisations

The inaugural MARAM Annual Survey of Organisations survey went live in April 2021 with a target population of 800 organisations prescribed under the Phase 1 MARAM rollout. Overall, 198 responses were received from 144 small, medium and large organisations across Victoria prescribed under MARAM. There were responses from specialist family violence services (including perpetrator interventions), (AOD services, homelessness services, child and family services, designated mental health, some prescribed functions within Aboriginal organisations, public housing, RAMPs, The Orange Door and Maternal and Child Health services to name a few.

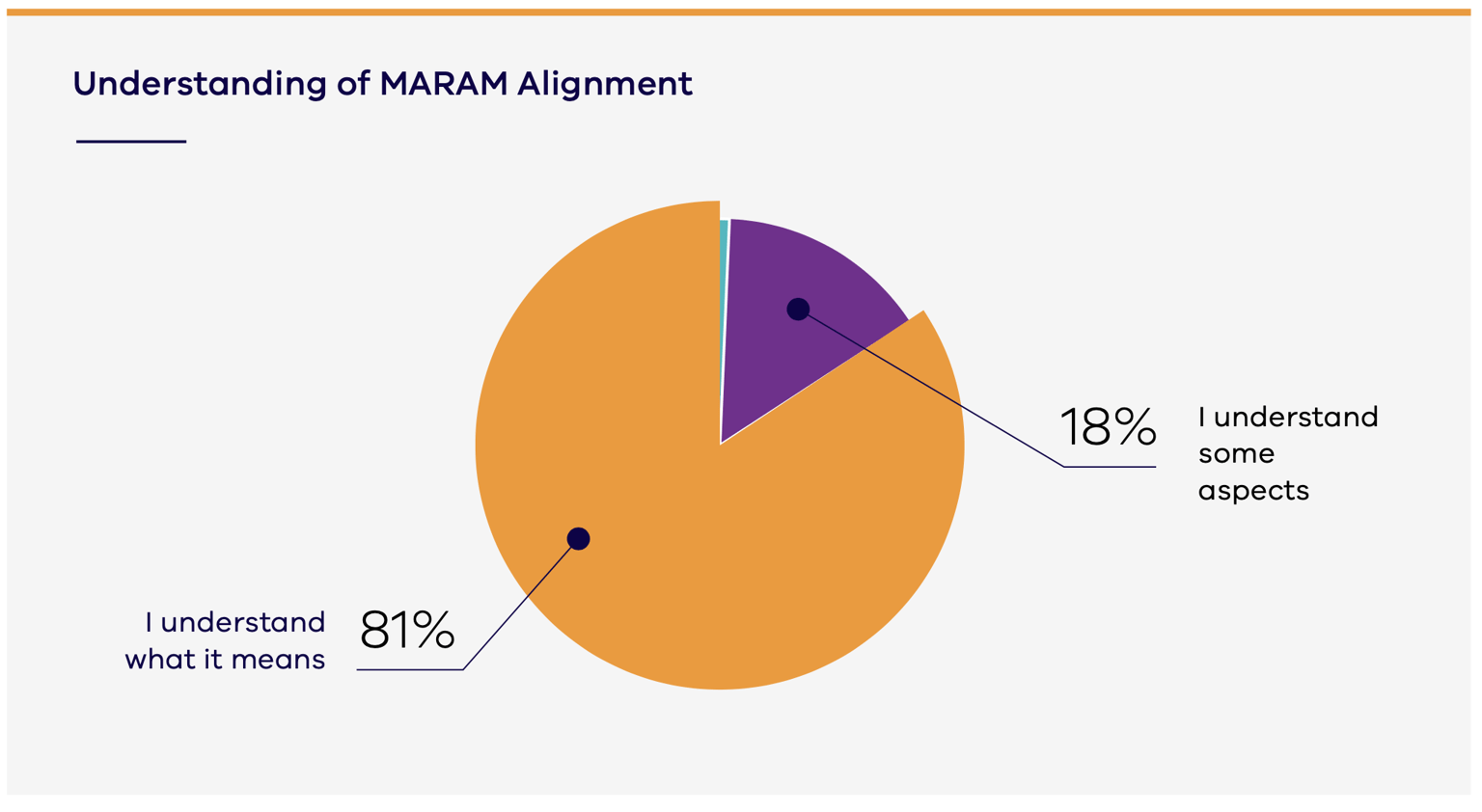

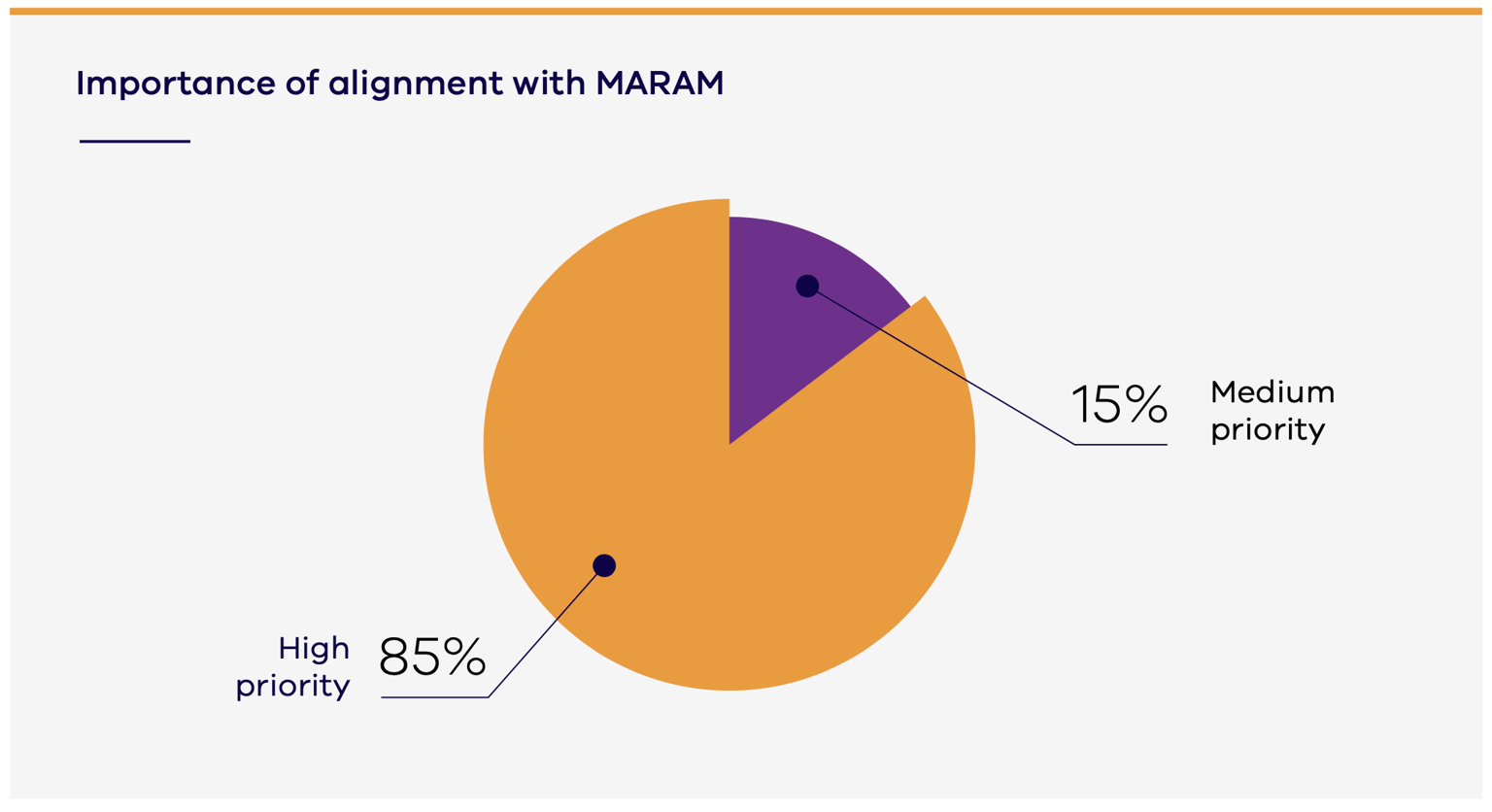

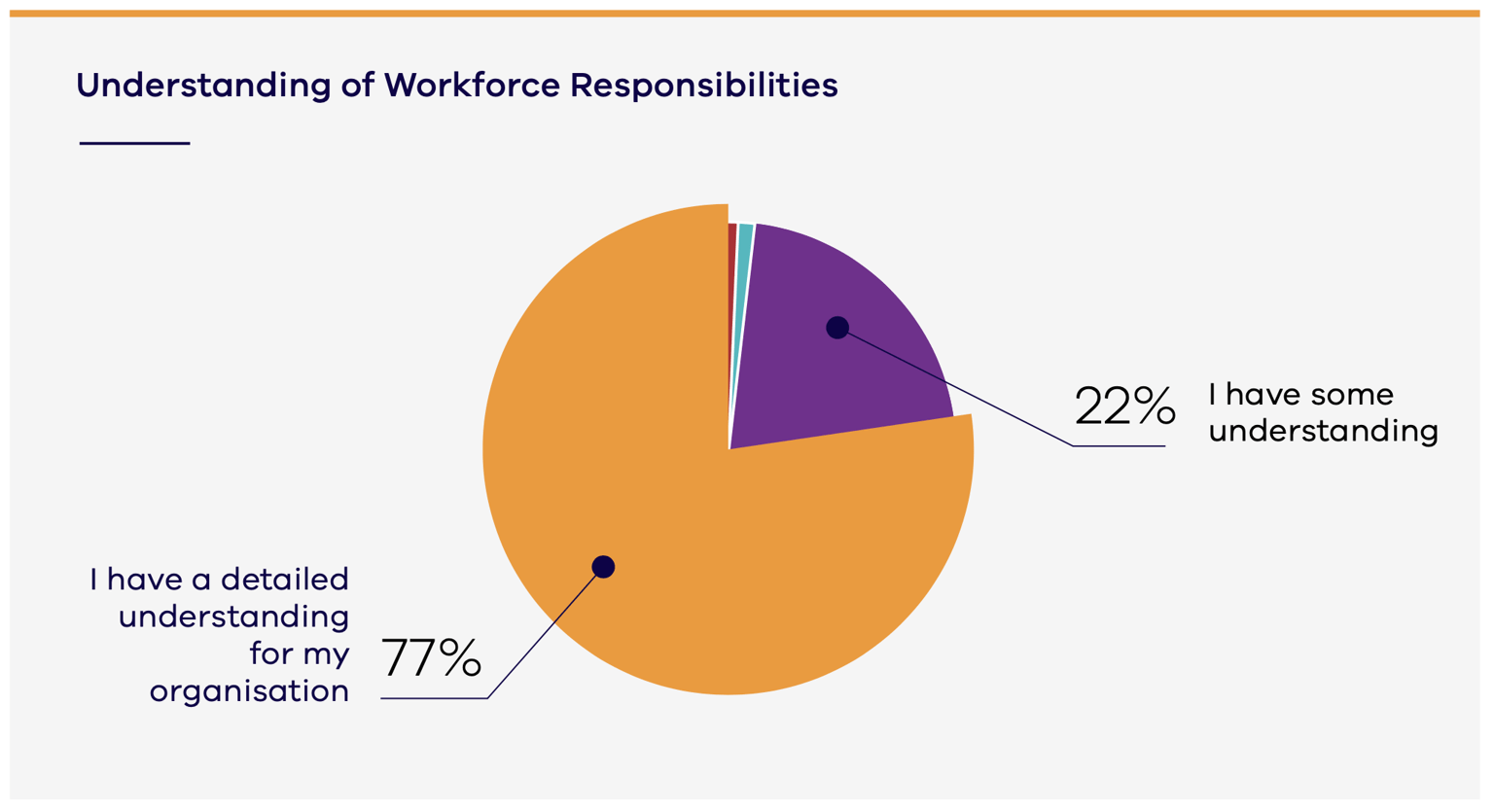

The survey results suggest that the large majority (81%) of organisation leaders understand what organisational alignment to MARAM means. Other results include:

- 85% said it was a high priority for their organisation to align to MARAM

- 77% said they have a detailed understanding of the MARAM responsibilities that impact their organisation

- 70% said “Lack of staff time” and/or “Prohibitive current workload of staff” was one of their top three challenges for MARAM implementation

- 47% said “Lack of organisational funding for MARAM implementation” and/or “Lack of time to update policies, procedures and practices” was one of their top three challenges.

These results were largely consistent across all workforces.

Future MARAM evaluation: the five-year review in 2023

MARAM is established in law under Part 11 of the FVPA. Under s. 195 of the FVPA, the Minister must cause a review of the operation of Part 11 to be conducted within five years after the commencement of the Part. The review must:

- assess the extent to which this Part is achieving the objective of providing a framework for achieving consistency in family violence risk assessment and family violence risk management

- recommend any required changes to improve the effectiveness of this Part in achieving that objective.

FSV intends to conduct this review in combination with the five-year reviews of FVISS (including CIP), also required under Part 5A of the FVPA. FSV will develop and finalise the scope and detailed approach for the combined five-year review mid to late 2021, with a view to commencing the review by mid-2022.

There is also a range of research and evaluation activity underway or planned to build the evidence about experiences of family violence, family violence risk and risk factors for Victoria’s diverse communities, including:

- the Everybody Matters Monitoring Plan, which will be completed in 2021-22, with monitoring efforts to ongoing across the life of the 10-year Everybody Matters: Inclusion and Equity Statement

- evaluation of the Multicultural COVID-19 Family Violence Program.

A Harmony Study will be conducted by La Trobe University, due for completion in June 2022, with government and sector oversight. The study aims to test the feasibility and effectiveness of a systems intervention to increase identification and early intervention of family violence and will be relevant to MARAM alignment activities for this sector.

MARAM Maturity Model

The MARAM Maturity Model was proposed early in the development of the MARAM Framework in recognition of the need to provide guidance to prescribed organisations as to their expected alignment pathway, noting that this would vary considerably across different sectors. The model is intended to be one of the key supporting resources for the MARAM Framework. Sitting alongside the MARAM Practice Guides and Organisational Embedding Guide, which support organisations to understand what steps they should take to align with MARAM and provide guidance on risk assessment and management responsibilities, the Maturity Model will provide a means for organisations to assess their level of progress in taking these alignment steps. It will do this by providing benchmarks against which organisations can compare their alignment progress.

The Cube Group report recommended the development of the Maturity Model to provide a common language for organisational improvement and to set out clear expectations for prescribed organisations’ alignment with MARAM.

Work commenced in early 2021, with an initial focus on settling a high-level design to test and develop further with stakeholders. The high-level design of the Maturity Model, which will be further tested and developed with government and nongovernment stakeholders in the next phase of work, is expected to have the following key components:

- alignment products –this describes products that help organisations apply the Maturity Model in practice. At a minimum, this will include a maturity matrix that will identify a number of alignment dimensions and outline a series of stepped benchmarks against these towards full alignment maturity

- defined improvement cycle –an approach drawn from existing maturity models in use in other policy areas, which will align with the Organisational Embedding Guide. The improvement cycle will consist of three defined steps:

- Assess and Audit – enabling organisations to self-assess their current level of alignment and utilise the improvement cycle’s self-evaluative approach to identify areas for improvement

- Plan and Implement – utilising the findings of the self-assessment process to set and act on improvement goals

- Review – reviewing the outcomes from the planning and implementation stage and informing a new cycle

- roles and responsibilities in government –consistent with the overall approach to MARAM oversight, responsibility for overseeing the Maturity Model will be distributed across government. As part of the Maturity Model design, work will be needed to determine how responsibilities can best be allocated across departments to match the distributed approach to MARAM oversight.

Summary of progress

Just over one year on from the early evaluations and progress continues in meeting the recommendations. The legislation requires a review of the operation of MARAM within five years of commencement, by 2023, which must:

- whether the MARAM reforms are achieving the objective of providing a framework for achieving consistency in family violence risk assessment and management; and

- recommend changes required (if any) to improve the effectiveness of the reforms in achieving that objective[27].

It is expected the outcome of the five-year review will inform future implementation activities.

The commencement of the MARAM annual survey will, over time, provide additional data on implementation progress, noting that its impact may be limited given it is voluntary. However, the development of the Maturity Model will seek to include a mechanism to enable continuous improvement.

[26] Victorian Government 2020, Report of the Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor 1 November 2020, https://www.fvrim.vic.gov.au/report-family-violence-reform-implementati…

[27] Family Violence Protection Act 2008, Section 195 http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/vic/consol_act/fvpa2008283/s195.html

Updated