- Date:

- 4 Dec 2023

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge country and we recognise those who have been harmed by family violence.

Acknowledgement of Country

The Department of Families, Fairness and Housing acknowledges Aboriginal people as the First Peoples and Traditional Owners and Custodians of the land and water on which we rely.

Acknowledgement of people with lived experience of family violence

The Department of Families, Fairness and Housing acknowledges adults, children and young people who have experienced family or sexual violence, including within our workforce.

Acknowledgement of partners

The Department of Families, Fairness and Housing acknowledges the expertise and knowledge of those organisations who have contributed to this document.

Acknowledgement of Country

The Department of Families, Fairness and Housing acknowledges Aboriginal people as the First Peoples and Traditional Owners and Custodians of the land and water on which we rely. We acknowledge and respect that Aboriginal communities are steeped in traditions and customs built on a disciplined social and cultural order that has sustained 60,000 years of existence. We acknowledge the significant disruptions to social and cultural order and the ongoing hurt caused by colonisation.

We acknowledge the ongoing leadership role of Aboriginal communities, particularly Aboriginal women, in addressing and preventing family violence and will continue to work in collaboration with First Peoples to eliminate family violence from all communities.

Acknowledgement of people with lived experience of family violence

The Department of Families, Fairness and Housing acknowledges adults, children and young people who have experienced family or sexual violence, including within our workforce. We recognise the vital importance of family violence system and service reforms being informed by their experiences, expertise and advocacy.

These guidelines are informed by insights from people with lived experience of family violence, including representatives of the Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council (VSAC). We are particularly grateful for their assistance ensuring the guidelines reflect the perspectives of practitioners with lived experience of family violence.

Acknowledgement of partners

The Department of Families, Fairness and Housing acknowledges the expertise and knowledge of those organisations who have contributed to this document including:

- Safe and Equal and its member organisations

- No to Violence and its member organisations

- Sexual Assault Services Victoria and its member organisations

- Centre for Excellence in Child and Family Welfare and its member organisations

- Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council members

- Family Violence Principal Strategic Advisors

- Family Safety Victoria and broader departmental staff.

We are grateful for the significant contribution of expertise and knowledge from Daphne Yarram, Chief Executive Officer of Yoowinna Wurnalung Aboriginal Healing Service, and her team to these guidelines. We acknowledge that the department is not the custodian of this knowledge. Where people are seeking to reproduce information in these guidelines related to First Nations peoples, they should engage with their local Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations to ensure it is culturally safe for their organisational context and location.

Introduction

These guidelines present best practice guidance and examples to help the family violence, sexual assault and child wellbeing sectors (the sectors) provide regular and effective supervision for their workforces.

They set out the level and quality of supervision future graduates and career changers can expect.

They also aim to support the wellbeing and sustainability of the current workforce. This will help to improve attraction, recruitment and retention in the sectors.

'Supervision is a priority, not a luxury.'

- Hewson and Carrol, 2016

Why we need the guidelines

Supervision is central to developing and sustaining the sector’s workforces.

About the guidelines

The standards were developed with the sector and while adhering to these standards is not mandatory, they are recommended as best practice.

Audience for the guidelines

The guidelines recognise that supervisors and supervisees come from various backgrounds and professional disciplines.

Why we need the guidelines

Supervision is central to developing and sustaining the sector’s workforces. It allows the exploration of:

- roles and responsibilities of sector practitioners, including risk assessment, therapeutic support, engagement, safety planning and collaborative multi-agency responses to family violence

- roles and responsibilities of supervisors

- adult, child and young person victim survivors’ experience and narrative

- how to work in a nuanced way with young people who can be both victim survivors of and display family and sexual violence

- respecting victim survivors as experts of their own lives and valuing their assessments of their own safety and needs

- how to practise safe, non-collusive communication with perpetrators

- anti-collusive practices which invite personal accountability for perpetrators’ use of family violence and sexual violence, and their related failure to protect children by using violence

- gendered drivers of family violence such as the beliefs, attitudes and social norms about gender that can lead to condoning of violence against women and rigid gender stereotyping

- both perceived and real risks to supervisee safety, including fears practitioners have working directly with perpetrators[1] or providing after-hours outreach services

- applying an intersectional lens and understanding supervisee/supervisor biases, including how people from First Nations, LGBTIQA+, culturally diverse communities or at-risk age groups may experience barriers, discrimination and inequality

- providing practitioners with lived experience of family violence and sexual assault with practice support and encouragement to practise self-care

- providing First Nations practitioners with support to carry the cultural load

- how to embed cultural safety, in line with the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural safety framework[2]

- how a supervisee's family of origin[3] or creation may affect their client assessments and interactions

- how to be more strengths-based and collaborative with clients, colleagues and other professionals

- individual practitioner and organisational power, and structural and systemic privilege and oppressions across the sector[4]

- the multi-faceted nature of supervision, including reflection, case discussions, support, professional development, clinical and managerial functions.

Supervision can support practitioners to enhance risk assessment, therapeutic support, engagement and safety planning. It also supports supervisors to enhance their leadership skills, understanding of workforce dynamics and needs and the provision of reflective supervision.

The sector has a highly skilled, dedicated, and resilient workforce, who, for decades, have embraced the importance of supervision and reflective practice (active process of witnessing an experience, examining it, and learning from it). The prevalence and severity of family violence have escalated. This, combined with the prescribed responsibilities under the Family Violence Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management (MARAM) Framework, including a greater focus on collaborative practice and intersectionality, means providing effective supervision has never been more crucial.

‘Paying attention to improving supervision quality can have far-reaching effects and be one of the most cost-effective ways of turning around an organisation.’

— Wonnacott, 2012[5]

The guidelines do not set out to change what is already working within the sector, but will:

- provide an opportunity for programs and organisations to review their supervision policies and practices and consider sector thinking and what other programs have found useful

- apply to family violence, sexual assault and child wellbeing sectors, acknowledging that these workforces have different skill sets and role requirements

- set the foundation for achieving more uniform, standard definitions, models, principles and practices of supervision across the state

- explore complex concepts and theories in terms of how they relate to supervision and provide further reading if the sector wants to delve deeper

- support the commitment government made in the Dhelk Dja Partnership Agreement of ensuring self-determined, strengths-based, trauma-informed, and culturally safe practices are built into policies and practice, and the broader family violence service system and its workforce

- signal to potential graduates and career changers entering the sector that their learning, support and wellbeing needs will be taken seriously

- support a culture of learning and professional growth

- invigorate conversations about best practice and some of the tensions and challenges inherent in providing regular and effective supervision.

References

[1] Family Safety Victoria, Family violence multi-agency risk assessment and management framework, Victorian Government, 2018, accessed 27 Feb 2023.

[2] Department of Families, Fairness and Housing, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural safety framework, DFFH website, 2019, accessed 13 June 2023.

[3] B Lackie, ‘The families of origin of social workers’, Clinical Social Work Journal, 1983, 11(4): 309–322, doi:10.1007/BF00755898.

[4] Family Safety Victoria, Family violence multi-agency risk assessment and management framework.

[5] J Wonnacott, Mastering social work supervision, Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London, 2012.

About the guidelines

The guidelines include:

- definitions of supervision, including clinical and managerial supervision

- the functions of supervision and how they fit with reflection

- information about reflective supervision and the values and theories underpinning supervision

- guidance on the role of supervisees, supervisors and organisations

- best practice standards regarding supervision frequency, duration, supervisor to supervisee ratio, supervisor training and supervision notes

- recommended reading for supervisors and supervisees who would like to know more about supervision

- examples of supervision agreement and care plans which can be used or adapted by the sector.

The standards were developed with the sector and while adhering to these standards is not mandatory, they are recommended as best practice.

The guidelines complement:

- existing supervision policies and procedures within the sector

- existing supervision professional development and training

- recruitment and induction procedures and processes, noting the importance of including interview questions exploring the applicant’s commitment to providing and/ or receiving supervision

- peak body practice standards, including Safe and Equal’s Code of practice: principles and standards for specialist family violence services for victim-survivors, the CASA Forum Standards of practice 2014, and the Men’s behaviour change minimum standards 2018

- the MARAM practice guides: guidance for professionals working with adults using family violence

- the shift to mandatory minimum qualifications for specialist family violence practitioners

- the Australian Association of Social Workers (AASW) Supervision standards 2014 and AASW Practice standards 2023

- Australian Community Workers Association Ethics and standards

- graduate programs which include a focus on supervision

- the Family violence experts by experience framework, which noted that a significant number of family violence practitioners have experienced family violence and further discussions about how to value and harness the strengths and insights of the workforce’s lived experience was required

- a culture reinforcing the health, safety and wellbeing of workforces and the online Family violence, prevention and sexual assault health, safety and wellbeing guide and Safe and Equal’s Self-assessment tool

- the Family violence capability frameworks for prevention and response

- access to debriefing and Employee Assistance Programs (EAP)

- collective advocacy to help transform unfair systems and practices, which plays a role in supporting workforce sustainability and retention

- other key workforce projects, research into workforce development and broader community services workforce development initiatives.

Audience for the guidelines

The guidelines are for students on placement, volunteers, administration staff, practitioners, team leaders, coordinators, managers, supervisors in private practice and management of the Victorian family violence, sexual assault and child wellbeing sectors.

This includes:

- The Orange Door

- specialist family violence services

- specialist sexual assault services

- services that operate after hours

- child and family services.

The guidelines recognise that supervisors and supervisees come from various backgrounds and professional disciplines. They can be adapted to suit different contexts. Using the guidelines is just one strategy to strengthen supervision – and most programs and agencies already have effective supervision policies and practices in place.

Although the guidelines have not been written specifically for Aboriginal community-controlled organisations (ACCOs), ACCOs may still find them useful. Similarly, this information may be helpful for the broader community services sector.

The information applies to:

- one-to-one supervision

- group or peer supervision sessions

- policy development

- supervision training.

Definitions

Defining supervision within the sector is complex. It is difficult to capture the intricate balance required to develop and maintain trusting professional relationships.

Ideally, supervision offers supervisees authenticity by talking openly about emotional responses to processing stories of family violence and sexual harm.

Supervision is essential for all practitioners working with trauma and interpersonal violence and those who:

- invite engagement and directly (or indirectly) work with adults using family and sexual violence, while applying non-collusive practice

- work with children and young people exhibiting concerning or harmful sexual behaviours or family violence, while applying a trauma- and violence-informed lens

- often work with unpredictable and serious levels of risk related to adults, children and young people experiencing violence

- may feel responsible to stop violence or abuse and to get justice for clients, especially for practitioners with lived experience of family or sexual violence.

Supervisors have a complex role. They must balance supporting supervisees, client needs and ethical practice. Supervision creates opportunities to discuss these tensions, and to support and sustain practitioners in their challenging, complex work.

Supervision

Supervision is an interactive, collaborative, ongoing, caring and respectful professional relationship and reflective process. It focuses on the supervisee’s practice and wellbeing. The objectives are to improve, develop, support and provide safety for practitioners and their practice.[1] It is ideally strengths-based and supervisee-led, where the supervisor adapts to supervisees’ preferences.

The sector expects supervision to incorporate an intersectional feminist lens. This allows discussion about power differences within the supervisory relationship, practice with clients and the broader system. It helps promote justice-doing, advocacy and community activism on behalf of clients and workforces.

Supervision enables monitoring of supervisee wellbeing and providing tailored support. Using a trauma- and violence-informed approach allows supervisors to normalise practitioner reactions to working within an imperfect system and working with people experiencing trauma and significant life events. The emotional toll of the work and vicarious trauma can be acknowledged during supervision in an empathic, understanding way, rather than blaming or pathologising.

Supervision supports a collaborative approach with clients, especially when setting goals, developing care plans and reviewing therapeutic objectives. It also provides a forum to:

- consider the unique professional development needs and preferences of each supervisee

- adopt a variety of supervisory styles (teaching, mentoring, coaching)

- consider child-centred approaches alongside the application of an intersectional feminist lens

- reflect on interpersonal boundaries,[2] essential in family violence and sexual violence work.

‘Supervision is vital to recognising and valuing the skills and capacity of practitioners.’

— Jess Cadwallader, Principal Strategic Advisor, Central Highlands

The sector often refers to managerial or line management and clinical supervision. The above definition aligns to both, and they are defined in more detail below.

References

[1] W O’Donoghue, cited in CE Newman and DA Kaplan, Supervision essentials for cognitive-behavioural therapy, American Psychological Association, 2016, doi:org/10.1037/14950-002.

[2] National Association of Services Against Sexual Violence (NASASV), Standards of practice manual for services against sexual violence, NASASV website, 3rd edn, 2021, accessed 27 February 2023.

Managerial or line management supervision

This supports organisational requirements and processes for practitioners to do their jobs and achieve positive outcomes for victim survivors.

Usually supervisor-led, this type of supervision is more task-focused and less reflective. When it includes reflection, it is usually for technical and practical aspects rather than deeper critical or process levels.[1] Managerial supervision helps align practices with organisation policies and relevant legislation. It includes discussing future career pathways and learning opportunities, both formal and informal.

Reference

[1] G Ruch, ‘Relationship-based practice and reflective practice: holistic approaches to contemporary child-care social work’, Child and Family Social Work, 2005, 10(2): 111–123, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2206.2005.00359.x.

Clinical supervision

Clinical supervision aims to develop a supervisee’s clinical awareness and skills to recognise and manage:

- personal responses

- value clashes

- power imbalances

- ethical dilemmas.[1]

Usually supervisee-led, this type of supervision allows deeper insight to the work using process reflection.[2] This is where conscious and unconscious aspects of practice and supervisory relationships are explored.

A clinical supervisor can be from outside of the organisation or be an internal line management supervisor or a supervisor who does not have line management responsibilities.

Having distinct roles for clinical and managerial supervision can help ensure critical and process reflection occurs.

‘Supervision is their time, it’s not my time.’

— Ivy Yarram, Yoowinna Wurnalung Aboriginal Healing Service

References

[1] State of Victoria, 2019–20 census of workforces that intersect with family violence: survey findings report – specialist family violence response workforce, Victorian Government website, 2021, accessed 27 February 2023.

[2] Ruch, ‘Relationship-based practice and reflective practice: holistic approaches to contemporary child-care social work’.

Cultural empowerment

Cultural empowerment[1] is a reflective, holistic, validating, non-judgemental, two-way learning process provided by a supervisor who is skilled, experienced, caring, respectful and knowledgeable about their local First Nations community.[2] The relationship should empower supervisees by reducing barriers for First Nations supervisees to perform their duties in a culturally safe environment.

First Nations workforces in Victoria need culturally safe empowerment.[3] It provides cultural context when reflecting on practice. It incorporates a strengths-based and person-centred approach that acknowledges a supervisee’s sense of pride and purpose in being able to impart cultural knowledge to others. It is recommended for First Nations supervisees and non-Aboriginal supervisees who work with First Nations people and communities.

To be effective, supervisors and colleagues need to understand why culturally safe empowerment is important. This requires awareness and understanding of the history and subsequent issues and challenges for First Nations supervisees. Such challenges include working closely with their own community and carrying the ‘cultural load’.

Cultural load

Cultural load[4] refers to multiple elements of stress, pressure and obligation that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander practitioners can experience in their professional roles. These pressures are outside the normal boundaries and expectations of other professionals working in community services. Cultural load can include:

- the often-unrecognised expectation to provide Indigenous knowledge, education and support to non-Aboriginal practitioners

- cultural obligations to client family members within community that involve support outside normal hours

- experiencing racism or cultural ignorance or assumptions in the workplace that need to be addressed and which take an emotional toll

- dealing with intergenerational trauma and lateral violence within community.

There are different elements of cultural load. In workplaces, these include the following:

- Employers may knowingly or unknowingly expect First Nations practitioners to provide Indigenous knowledge, education and support to other practitioners. This often occurs without any formal reduction or alteration of their other work.

- First Nations practitioners often live in the communities they work with. These community relationships can affect practitioner–client relationships and practice. In particular, it can often mean First Nations practitioners need to meet cultural obligations to client family members outside of work hours, which requires energy and time.

- First Nations practitioners who work on lands where they are not a Traditional Owner have different obligations to that community. These derive from a complex ‘adopted relationship’. This can involve being guided by Traditional Owners and Elders to fulfil cultural responsibilities that lie outside a professional work context.

- Being the only First Nations practitioner in an organisation can be particularly difficult and isolating in the context of carrying the cultural load alone. There is often a sense of responsibility to accurately represent the community. It can also sometimes involve having to experience and deal with either racist or unintentional cultural ignorance or cultural assumptions by team members.

- The overlay of transgenerational trauma, complex community relationships and lateral violence which adds to the ‘load’.

First Nations practitioners want and need to have their cultural load recognised and respected as an important aspect of their role. They also need culturally safe space during supervision to reflect on this role and its impact on them, including the conflicts and challenges.

Supporting cultural empowerment

Supervisors and colleagues should have appropriate cultural awareness training to be aware of their roles and responsibilities when working alongside First Nations supervisees. Non-Aboriginal services need to also recognise that some aspects of cultural empowerment and connection can only be gained and shared between First Nations people. Cultural meaning and practices will be different from non-Aboriginal norms and belief systems.[5]

The Yarn Up Time and the CASE model[6] offer guidance on how to provide culturally responsive supervision for First Nations practitioners and non-Aboriginal practitioners working with First Nations communities.

References

[1] Note that the word supervision can have negative connotations of control and regulation for the First Nations workforce.

[2] Victorian Dual Diagnosis Education and Training Unit, Our healing ways: a culturally appropriate supervision model for Aboriginal workers, Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet website, 2012, accessed 27 February 2023.

[3] Victorian Dual Diagnosis Education and Training Unit, Our healing ways: a culturally appropriate supervision model for Aboriginal workers.

[4] Although cultural load in this section refers to First Nations people, members of other culturally and racially marginalised communities may also experience an additional ‘load’ in the workplace.

[5] Western Sydney Aboriginal Women’s Leadership Program, Understanding the importance of cultural supervision and support for Aboriginal workers,2013, accessed 27 February 2023.

[6] T Harris and K O’Donoghue, ‘Developing culturally responsive supervision through Yarn Up Time and the CASE Supervision Model’, Australian Social Work, 2019, 73(5):1–13, doi: 10.1080/0312407X.2019.1658796.

Intersectional feminist supervision

This recognises how different aspects of a person’s identity might affect how they experience the world and the related barriers.[1] An intersectional feminist lens encourages supervisors and supervisees to question their own experiences and how they might create assumptions about another’s experience. It assists supervisees to:

- better understand how different forms of marginalisation impact others

- reflect on own lived experience of power, privilege and oppression and the impacts on work with clients and other professionals[2]

- consider the system more broadly

- be more targeted in their advocacy for improving gender and broader equality.

It also helps practitioners appreciate the need for personalised and tailored solutions.

The message that ‘personal is political’[3] is critical, as is the role of the supervisor to create this awareness for the supervisee. Supervisors can use supervision to examine the effect of hierarchies and the power differential between the supervisor and supervisee. It is crucial for supervisors to critically reflect on their own position of power and avoid taking a paternalistic approach to supervision. The aim is to create a more empowering and egalitarian relationship.[4] The notion that the ‘personal is professional’ and bringing your whole self to work can also be considered a feminist act.[5]

‘Checking your privilege isn’t about creating a sliding scale of who’s worse off – it’s about learning and understanding the views of other feminists and remembering that we’re all in this together. True equality leaves no-one behind.’

— International Women’s Development Agency[6]

Cultural responsiveness and inclusion

It is important to provide supervision that is culturally responsive and inclusive. This means:

- respecting cultural identity and beliefs

- recognising and supporting cultural strengths as part of supervision

- valuing diversity

- understanding the intersecting aspects of a person’s identity

- adopting an empowering rather than paternalistic approach

- providing a space that is trauma- and violence-informed, strengths-based and person-centred[7]

- considering individual needs, for example, ensuring that supervision is accessible for a person with a disability

- exploring responses to client identities, challenging assumptions and considering how these identities can offer strength, connection and resistance, in addition to exploring their experiences of discrimination.

References

[1] International Women’s Development Agency (IWDA), What does intersectional feminism actually mean? IWDA website, 2018, accessed 27 February 2023.

[2] Domestic Violence Victoria , Code of practice: principles and standards for specialist family violence services for victim-survivors, Safe and Equal website, 2nd edn, 2020, accessed 6 October 2023.

[3] C Hanisch, ‘The personal is political’, in S Firestone and A Koedt (eds), Notes from the second year: women’s liberation, Radical feminism, New York, 1970.

[4] CA Falender and EP Shafranske, ‘Psycho-therapy based supervision models in an emerging competency-based era: a commentary’, Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 2010, 47(1): 45–50, doi: 10.1037/a0018873.

[5] A Morrison, The personal is the professional, Hook & Eye website, 2010, accessed 27 February 2023.

[6] IWDA, 3 ways to be an intersectional feminist ally, IWDA website, 2017, accessed 27 February 2023.

[7] Family Safety Victoria, Everybody matters: inclusion and equity statement, Victorian Government website, 2018, accessed 21 August 2023.

Link with other supports

Although they overlap, supervision is different to formal debriefing, critical incident management and day-to-day management interactions. These need their own policies and procedures.

Performance management is also separate to supervision but, through early recognition and support, supervision can prevent performance concerns growing.

Supervisors need to use empathy and counselling skills during supervision. How much will depend on the situation and supervisee. The line between supervision and counselling is fluid. It reflects supervisees bringing their ‘whole selves’ to the work. Personal experiences can support the work. Deep reflection during supervision provides opportunities to:

- unpack personal experiences that affect practice and vice versa

- allow supervisees to feel supported and maybe seek ongoing external help if required, through EAP or therapy

- monitor the safety and wellbeing of supervisees, their levels of vicarious trauma and possible burnout.[1]

Develop a supervision agreement early in the relationship. This is an opportunity to discuss the fluid nature of supervision and normalise the potential need for EAP or a therapeutic response.

‘One of our practitioners wasn’t sure why a particular client triggered her. We were able to talk it through in the moment and when we unpacked it, it went right back to her early years. Providing space for in-the-moment supervision meant that she was able to make that link. I then referred her to the EAP, so she had the opportunity to explore it further through ongoing therapeutic work with someone else.’

— Kelly Gannon, Team Leader, Winda-Mara Aboriginal Corporation

References

[1] Hewson and Carroll, Reflective practice in supervision.

Supervision models

There are many supervision models, such as the PASE[1], 7-eyed[2] and 4x4x4[3] models.

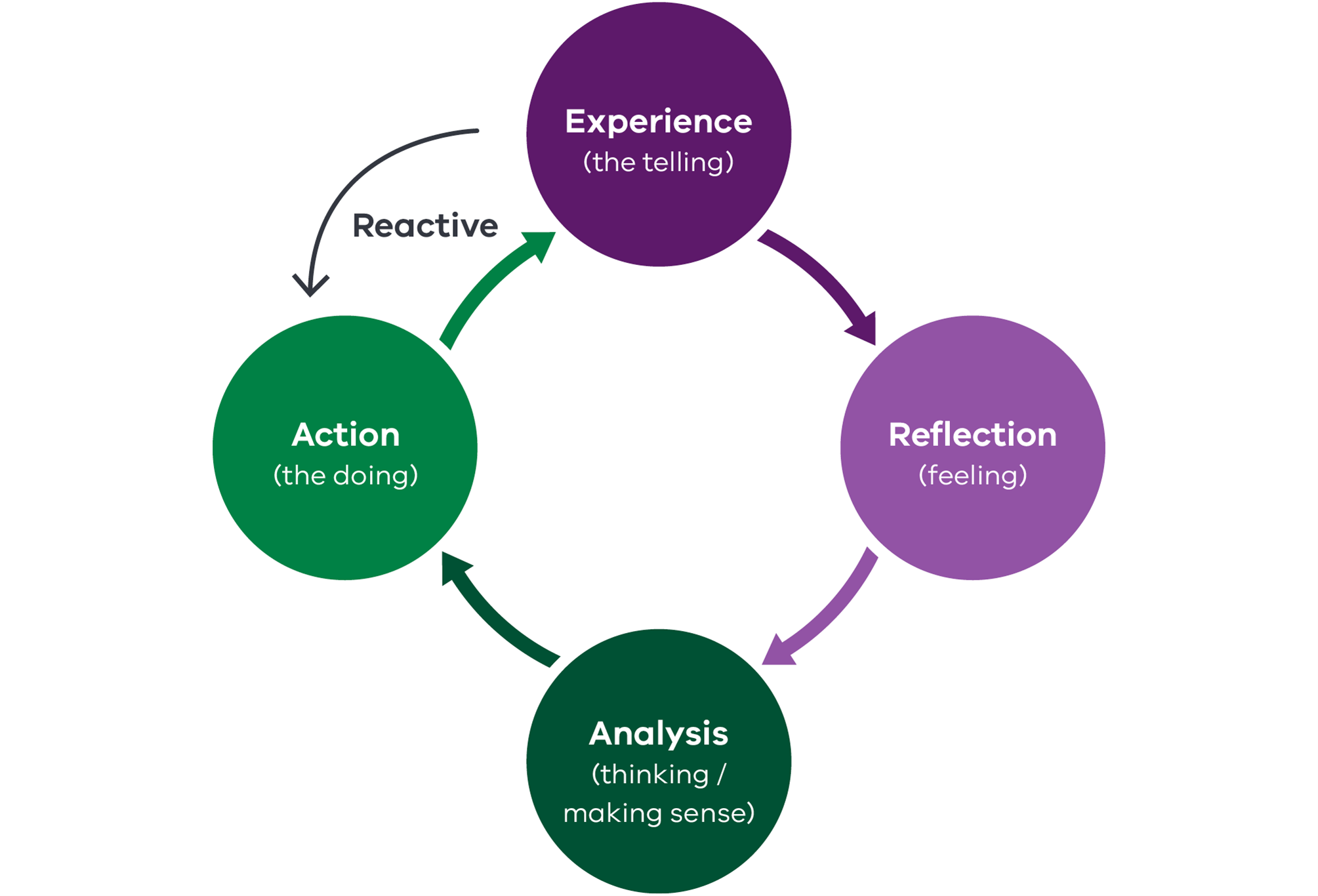

The 4x4x4 integrated model of supervision is used in many Victorian sectors, including child protection. It includes the three functions outlined in the AASW Supervision standards 2014.[4] The 4x4x4 model helps to promote reflective supervision and locate it within the context within which supervision occurs by including:

- the four functions of supervision (support, management, development and mediative)

- the Kolb learning cycle (experience, reflection, analysis, plan and act) that underpins reflective practice[5]

- the context in which supervision occurs or stakeholders.

The supervision functions provide the ‘what’ of supervision. The stakeholders are the ‘who’ or ‘why’ in supervision. The reflective learning cycle is the ‘how’, or the glue that holds the model together. It ensures supervision is a developmental process which improves supervisee practice and decisions, as well as their insight about themselves and their work.

References

[1] Amovita International, Amotiva [website], Amovita, n.d., accessed 13 February 2023.

[2] P Hawkins and R Shohet, Supervision in the helping professions, Open University Press, 2006.

[3] T Morrison, Staff supervision in social care, Pavilion, Brighton, 2005.

[4] Australian Association of Social Workers (AASW), Supervision standards, AASW website, 2014, accessed 13 June 2023.

[5] DA Kolb, Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1984.

Four functions of supervision

Supervision serves several functions. These overlap and occur to varying degrees depending on the context, supervisory relationship and organisation. A clear separation of the functions is never entirely possible, or desirable.

It can be difficult for supervisors to cover all four functions. Sector feedback and related literature show that there is often a lack of balance across the functions, with managerial supervision prioritised. Partly for this reason, some programs have separated clinical (supportive, developmental and systemic functions) from line management (managerial function) supervision. They have also provided peer supervision to ensure the more reflective functions occur.

The four functions of supervision are outlined in more detail below. Note that the sector prefers the term ‘systemic’ over ‘mediative’.

Supportive

- provides a forum to discuss confidentiality, develop trust and a supervisory alliance between supervisor and supervisee

- creates a safe context for supervisees to talk about the successes, rewards, challenges, conflicts, uncertainties, and emotional impacts (including vicarious trauma) of the work and to monitor supervisee safety and wellbeing

- provides an opportunity to explore vicarious resilience which can have significant and positive impacts on practitioner wellbeing and satisfaction since it identifies client strengths and signs of progress[1]

- explores supervisee’s own personal experiences (including current and previous trauma and lived experience), assumptions, beliefs, and values and how these can impact, and be used, in client practice and interactions with colleagues[2]

- explores the supervisee’s own experience of being parented, or of parenting their children, and how this might be influencing their judgements and practice when working with parents, caregivers, children, and young people

- works from the premise, and is sensitive to the reality, that many practitioners will have their own lived experience of family violence and sexual assault and the decision to disclose is a personal one[3]

- provides a space to recognise the impact of the work and identify when external supports may be needed such as EAP, clinical supervision or a therapeutic response

- helps maintain professional boundaries which are critical in sustaining the workforce

- engages the supervisee and supervisor in discussions about trauma- and violence-informed theory and practices, organisational culture and creating psychological safety

- recognises the potentially distressing and stressful nature of the work

- gives practitioners a restorative space to explore the impact of the work on their mental health, identity and work–life balance

- allows discussion about team wellbeing and how collective care can be enhanced.

Managerial

- promotes competent, professional and accountable practice

- checks supervisee understanding and compliance with policies, procedures and legislated requirements

- monitors workloads, hybrid working arrangements and work–life balance

- checks that the supervisee has the information and resources they need

- helps supervisees understand their role and responsibilities

- reflects on interpersonal boundaries and the work

- includes human resource tasks, such as leave requests.

Developmental

- establishes a collaborative and reflective approach for lifelong learning

- focuses on professional development

- supports those working to meet mandatory minimum qualification requirements

- helps embed the MARAM Framework and best interests case practice model for vulnerable children and young people into practice

- clarifies individual learning styles, preferences and factors affecting learning

- explores supervisee knowledge, ethics and values

- enables two-way constructive feedback and learning between supervisor and supervisee

- allows feedforward, which focuses on future behaviour and can be better received than feedback

- allows supervisors to coach more experienced practitioners via curious, reflective questions

- helps determine and support supervisee professional development or training needs.

Systemic

- explores power structures and inequalities in the work context and the supervisory relationship

- supports discussions about intersectional feminist theory, how intersectionality is contextual and dynamic, and requires ongoing reflection and analysis of power dynamics

- explores the relational power imbalances and lack of agency experienced by children and young people

- ensures culturally safe and informed supervision is available to First Nations practitioners, which recognises the extra layer of vicarious trauma that First Nations practitioners are exposed to and the cultural load they carry

- recognises that there is systemic discrimination and racism that is part of the cultural load an Aboriginal practitioner must carry in their work

- helps supervisees make sense of, relate to and navigate the broader system, sector changes and system limitations

- helps improve multi-agency collaboration

- provides a forum to consult about policies and organisational change

- provides important upward feedback about the frontline experience and interface with the system

- offers a forum to plan advocacy work on a systemic level.

References

[1] D Engstrom, P Hernandez and D Gangsei, ‘Vicarious resilience: a qualitative investigation into its description’, Traumatology, 2008, 14(3):13–21, doi:10.1177/1534765608319323.

[2] Hewson and Carroll, Reflective practice in supervision.

[3] D Mandel and R Reymundo Mandel, ‘Coming 'out' as a survivor in a professional setting: a practitioner's journey’, Partnered with a survivor podcast series, Safer Together, 2023.

Types of supervision

Scheduled or formal supervision

This type of supervision is regular, planned, one-to-one, uninterrupted and held in a private setting between the supervisor and supervisee.

Unscheduled or informal supervision

Unscheduled or informal supervision includes consultations on decision making, delegation, load management, professional development, support needs, service and resource allocation, and policy.

Live supervision

Live supervision involves direct supervision of case practice provided by a more senior practitioner

Group supervision and peer supervision

Group supervision is normally provided within an established team of practitioners.

Collaborative supervision

Supervision has traditionally been viewed as a relationship and process between one supervisor and one supervisee

Case study: Building a culture of supervision

Case study about building a culture of supervision within a team

Scheduled or formal supervision

This type of supervision is regular, planned, one-to-one, uninterrupted and held in a private setting between the supervisor and supervisee.

It provides the consistency and predictability needed to promote a positive relationship between supervisor and supervisee. This type of supervision must be prioritised over other forms of supervision to enhance workforce sustainability and service quality. It is often regarded the ‘heart of the process’[1] and is the most effective type of supervision for retaining practitioners.[2]

References

[1] Wonnacott, Mastering social work supervision.

[2] N Cortis, K Seymour, K Natalier, and S Wendt, ‘Which models of supervision help retain staff? Finding from Australia’s domestic and family violence and sexual assault workforces’, Australian Social Work, 2021, 74(1):68–82, doi: 10.1080/0312407X.2020.1798480.

Unscheduled or informal supervision

Unscheduled or informal supervision includes consultations on case decision making, delegation, staff and case load management, professional development, meeting support needs, service and resource allocation and policy clarification.

The nature of family violence, sexual assault and child wellbeing practice means that many complex issues cannot wait until a scheduled supervision session. Unscheduled supervision capitalises on learning opportunities which risk being missed if the supervisee waits until scheduled supervision.

Risks in prioritising unscheduled supervision include:

- it does not provide the supervisee with privacy and a space to talk about the work’s impact on themselves

- due to its time-pressured nature, it rarely provides opportunities for proper reflection

- it can be challenging to ensure decisions and rationales are properly documented.

Live supervision

Live supervision involves direct supervision of case practice provided by a more senior practitioner observing the supervisee in practice or accompanying the supervisee while engaging with children, families or other professionals.

This may include the more senior practitioner role-modelling, mentoring, coaching and promoting self-reflection. Live supervision can provide a more complete picture of the supervisee’s strengths and skills. It has the advantage of providing real-time feedback or feedforward, thereby increasing self-awareness, and improving clinical skills.

Live supervision can take different forms such as:

- supervisor and supervisee co-working on cases

- observing the supervisee in practice and the supervisor intervening only when helpful

- practice recordings for later exploration and reflection, noting that permission would be required from clients and supervisees.

Live supervision can be a highly useful learning experience for the supervisee if done well, but also risks being a disempowering experience if done less well. Once again, the relationship quality and trust between the supervisor and supervisee will be crucial.

Live supervision can also be beneficial for clients, who benefit from having input from two practitioners.

Group supervision and peer supervision

Group supervision is normally provided within an established team of practitioners. It comprises structured sessions, often involving case presentations that include a genogram of the family to assist discussions. The practitioner may reflect on their experience in working with a client or family and seek the assistance from the group around a particular aspect of their work.

Group supervision needs to involve the supervisor responsible for work standards and document any decisions arising from the discussions.

Peer supervision often has broader membership than a practitioner’s immediate team. It does not involve supervisors and is therefore not a decision-making forum. It offers peer learning, reflection and a support opportunity for cases, responses and practice. Supervisees can then further reflect on these discussions during individual supervision. Peer supervision may be self-led by the group of peer practitioners or facilitated by someone designated as the facilitator of the reflective discussions.

Both group and peer supervision need to facilitate critical reflection and address one or more of the supervision functions. Both need to prioritise the wellbeing of those involved. They can include discussions about their team care plan (see the Appendix for an example). It can be an invaluable addition to individual supervision, providing team members and peers the opportunity to:

- learn from and support one another

- normalise their shared experiences.[1]

Reference

[1] Cortis et al., ‘Which models of supervision help retain staff? Finding from Australia’s domestic and family violence and sexual assault workforces’.

Collaborative supervision

Supervision has traditionally been viewed as a relationship and process between one supervisor and one supervisee. This can put the supervisor in an unrealistic ‘expert’ role and one leader is unlikely to have the required skills and knowledge to meet all the needs of each supervisee.

There has been a shift to embracing a more collaborative model of supervision. There can be benefits from using multiple supervisors, as well as peer supervision. For example, The Orange Door networks developed a matrix model of supervision that incorporates home agency supervisors and practice leaders. This offers more expertise and consultation. Supervision agreements can assist in clarifying confidentiality, roles and communication channels in collaborative supervision.

Other programs include a mix of internal and external supervision, with external supervision being more clinical and reflective. Some programs use an external supervisor to facilitate peer supervision.[1] Individual practitioners also need to consider the supervision they need for their respective professional body registrations.

Regardless of the supervision arrangement, the regularity, quality, focus on reflective practice and the balance between the four functions, are the guiding factors in determining the adequacy of the arrangement.

For collaborative supervision to succeed, the following is recommended:

- everyone uses the same supervision model which clearly outlines the functions of supervision

- agreement regarding delegations and lines of accountability

- the responsibilities and actions, such as child protection reports, required for children and young people at risk are clear

- the line manager has overall responsibility for the team function and development across time

- the line manager has responsibility for monitoring and supporting the supervisees’ wellbeing

- the line manager has overall responsibility for ensuring regular reflection and all four functions of supervision are provided to each supervisee.[2]

References

[1] State of Victoria, 2019–20 census of workforces that intersect with family violence: survey findings report – specialist family violence response workforce

[2] Department of Human Services, Leading practice: a resource guide for child protection leaders, 2nd edn, State of Victoria, 2014, accessed 27 February 2023.

Case study: Building a culture of supervision

‘When I started as a team leader a year ago, there was an opportunity to formalise supervision and make it a regular occurrence.

I took the opportunity to really think about how I could support each person. For example, if someone was having difficulty with a client and they didn’t understand why they were being triggered by that person, bringing in formal supervision provided a space to unpack that so they could perform better. It also provided the opportunity to offer support around things like structural issues and oppression, workload, how the organisation works, and navigating uncertainty.

One of the most helpful things we did was draw up supervision agreements, which both the supervisor and supervisee sign. The agreement covers things like how the staff member likes to receive feedback, how they learn and how I can best support their learning, and the designated time we set aside for supervision to ensure we make time for it without interruptions.

Now that we’ve been working together for a while, it’s got to the point where I can walk into the office and I can tell by the looks on people’s faces how they’re travelling. Then how I respond to that depends on the individual and what might be culturally appropriate for each person.

In addition to formal supervision, I also have an open-door policy, so that my team can come and talk to me in moments when they are stuck rather than shutting it down until supervision. It is a helpful way to ensure the team can maintain work–life balance and put boundaries in place, so they don’t take the burden home with them.’

— Kelly Gannon, Team Leader, Winda-Mara Aboriginal Corporation, Health, Safety and Wellbeing seminar 1, February 2023

Role of the organisation, supervisor, and supervisee

Supervision is a shared responsibility. This means that the organisation, supervisor and supervisee all have a role in making supervision and the supervisory relationship work.

Some organisations think it is enough to have a supervision policy and structures in place to provide supervision. This ‘set and leave’ approach does not ensure quality supervision occurs and the needs of supervisees and supervisors are being met.

‘Too often we settle for having supervision rather than good supervision.’

—Wonnacott and Morrison, 2010[1]

Strong organisational leadership is key to improving and prioritising supervision practices. This includes systems that ensure regular supervision occurs. Strong leadership also involves displaying behaviours that support supervision, such as:

- putting ethics into practice

- embracing strengths-based approaches

- promoting advocacy and transparency

- applying principles of self-determination, cultural safety and trauma-informed practice.

The context in which supervision occurs matters and influences the supervisory relationship. Research shows that establishing a trusting and positive supervision relationship is a key driver to successful supervision.[2]

The following table can be applied to the different types of supervision to varying degrees.

Table 1: Supervision roles, responsibilities and outcomes

Organisation

| Role | Responsibility | Outcome |

| Provides direction and leadership about the importance of participating in supervision for all staff regardless of experience or level. | Ensures everyone has an understanding and appreciation of why supervision is important. Ensures all staff have an understanding how supervision, professional development and performance reviews are interconnected. Ensures participation in supervision is included in position descriptions and performance reviews. | Supervision is prioritised at every level. Expectations regarding supervision are documented and well understood.

|

Prioritises training about supervision and supports the development of supervisors.

| Prioritises induction/training about supervision, reflective practice and trauma- and violence-informed principles for new practitioners. Develops succession planning strategies and provides clear pathways to become a supervisor. Prioritises supervision training for new and experienced supervisors. | Staff have a clear understanding about supervision and their responsibilities. Supervision training is viewed as a necessity for all staff. Supervisors are supported in their role. |

Creates a culture supporting diversity, cultural safety in the workplace, and lived experience.

| Ensures workforce strategies include the provision of culturally responsive supervision to develop and advance Aboriginal staff. Creates a safe environment, which allows staff from diverse backgrounds to talk about their own experiences of marginalisation and encourages others to hear this with humility and curiosity about their unknowing. Creates a culture which embraces practitioners with lived experience of family violence and sexual assault. There are clear channels to input supervision learnings about lived experience in the workforce into relevant policies and forums. | Aboriginal staff, either in ACCOs or mainstream agencies, can access culturally safe clinical supervision as per the Dhelk Dja Agreement.[3] Staff understand how to embed cultural safety principles, policies and theory in supervision. Staff feel safe enough to disclose their own lived experience if they want to. |

Embraces trauma- and violence-informed principles - Prioritises psychological, physical and emotional safety.

| Understands possible causes of performance concerns such as systemic barriers, context, stress and workload. Facilitates discussions with the workforce about the culture and systems that can support and sustain effective supervision. Works towards having greater congruence between the policies and strategic goals with the actual organisational culture. | The organisation has a positive and safe workplace culture which incorporates trauma- and violence-informed practices and embraces compassionate leadership. |

Creates a ‘just’ culture, promoting lifelong learning and development.

| Allows vulnerability and an acceptance that mistakes can and do occur. Ensures continuous improvement processes are in place to support supervision. Develops mechanisms for practitioners to raise issues regarding quality of supervision and develop strategies to address this. | Staff feel valued and part of the solution-finding process and are provided professional development opportunities to develop own best practice.

|

| Ensures there are adequate resources to support supervision. | Ensures the ratio of supervisees to supervisor is manageable so that supervisors have the time and energy to provide quality supervision. Ensures there are suitable and private spaces for supervision to occur. | The organisation and supervisors have the resources they need to provide effective supervision. |

| Ensures supervision is high-quality and aligns with best practice approaches. | Embeds supervision within a trauma- and violence-informed culture. Understands, models and supports reflection and reflective supervision and practices across the organisation. | Staff understand core trauma- and violence-informed principles and theory and how this can positively impact on workforce sustainability and clinical practices. |

| Ensures that supervision aligns with relevant laws, agreements, and policies. | Complies with, and provides evidence, of meeting the Social Services Standards. Develops systems to monitor and ensure supervision regularly occurs. Ensures there are up-to-date policies and procedures regarding supervision. These need to consider issues regarding confidentiality. | The organisation meets regulatory and best practice requirements in providing quality supervision for all staff. |

| Coordinates and leads advocacy. | Supports centring the voices and experiences of victim survivors in advocacy and supervisory practice. Uses information from supervision to identify structural and system barriers affecting practice (systemic function).

| Supervision feeds into identifying structural and system barriers affecting practice and planning advocacy on a systemic level. |

Supervisor

| Role | Responsibility | Outcome |

| Ensures the supervisee understands what supervision is and sets the scene regarding mutual expectations and how they will work together. | Completes a supervision agreement with each supervisee and reviews every six months. Supports the supervisee in receiving supervision training. Continues discussions during supervision about the benefits and functions of supervision. | Supervisees have up-to-date supervision agreements. Supervisee and supervisor are aligned regarding their understanding of their roles in the supervision process.

|

Works to make supervision as effective as they can.

| Considers their energy levels, peak times of the day and ability to be present during supervision. Engages in supervision when centred and grounded, as much as possible given the fast-paced nature of the work. Adapts and tailors supervision to the needs of each supervisee. Engages with the organisation about the culture and system that can sustain supervisors in developing effective supervision. | Supervisor feels able and sustained to provide quality supervision. Supervisee feels supported, nurtured, heard and valued. All four supervisory functions are covered in supervision. |

| Supports the wellbeing of supervisees. | Monitors caseloads and provides an appropriate buffer to system demands. Checks in on how the supervisee is feeling during supervision sessions. Regularly asks what further support supervisees needs to perform the role. | Supervisees feel valued, seen, supported and respected. |

Creates learning partnerships with supervisees.

| Adopts an open and curious approach. Acknowledges that they do not know everything, and the supervisee can contribute to their own learning. Adapts, accommodates, and attunes to the supervisee’s learning preferences. Adopts a strengths-based approach. | Supervisees take responsibility and lead their own supervision sessions.

|

| Supports the professional development of the supervisee. | Explores additional training the supervisee needs and facilitates attendance. Focuses on family violence and sexual assault risk and follows up on risk management activities. Applies a child-centred and family-focused approach to practice during supervision. Uses the Family violence capability frameworks to identify further support needs with the supervisee. | Supervisees improve their levels of confidence, knowledge, skills and practice. Staff are aware of the accountabilities of their role. |

Co-creates and maintains a trusting relationship with the supervisee.

| Facilitates a trusting relationship where mistakes and anxieties can be explored and helps supervisees contain and process their emotions. Uses a ‘critical but mindful friend’[4] approach with the supervisee. Values supervisee input. | A trusting relationship develops between supervisor and supervisee such that challenging conversations can occur. Relationship ruptures and repairs are normalised. |

| Supports reflective practice. | Explores practitioner’s fears, and the factors influencing practitioner assessment of their own safety.[5] Uses a coaching approach whereby reflective questions are used to enhance supervisee insight and learning. Assists practitioners to reflect on how their own personal and professional history might impact their professional attitudes and behaviour.[6] | Supervisee experiences a reflexive stretch in most sessions.

|

Supports learning about diversity and focuses on cultural safety during supervision.

| Applies an intersectional feminist lens during supervision and other forums which allows staff from diverse backgrounds to talk about their individual experiences, with others hearing this with humility and curiosity about their unknowing. Considers cultural empowerment and explores the impacts of cultural load for First Nations staff. | Supervisees and supervisors are aware of their unconscious biases and adopt culturally safe practices. First Nations staff feel more supported in their role. |

Prioritises their own supervision.

| Reflects on their own supervisory and leadership style and considers the impact of this. Discusses their learning needs during their own supervision. Uses their own supervision and human resources support to explore use of formal authority, for example if there are performance issues. | Supervisor feels confident and supported in providing reflective supervision. Supervisor receives regular, quality supervision and grows as a supervisor.

|

| Explores differences in power relations at individual, team, organisation and systemic levels. | Reflects on the supervisor – supervisee power differential during supervision. Reflects on use of power in relationships and how to work collaboratively and in partnership with others. | Supervisees and supervisors are aware of power dynamics. Staff work in partnership with clients and other professionals. |

| Complies with supervision policies and laws | Ensures supervision notes/ records are kept, providing evidence of strength-based approaches, and supporting Aboriginal people to exercise their cultural rights.[7] | There is a record providing a brief outline of every supervision session. These are kept in a safe place to ensure confidentiality. |

Supervisee

| Role | Responsibility | Outcome |

| Commits to fully participate in and be open to supervision. | Co-creates, monitors and maintains a trusting relationship with the supervisor. Understands that being open about mistakes is a critical component of continuous improvement. Engages fully in supervision and accepts that it requires effort and ‘work’ on both parts. | Supervision sessions are purposeful and beneficial. Supervisee feels valued and supported by their supervisor, team and organisation. Supervisor feels engaged, valued, respected. |

Shares responsibility for their own learning and wellbeing needs.

| Engages in induction/ supervision training. Comes to supervision prepared, both physically and mentally. Understands the importance of collaborative supervision and seeks out alternate sources of supervision for their learning needs. Explores and discusses training options during supervision. | Supervisee learns about themselves, use of self in the work and about their role, responsibilities and professional boundaries.

|

Helps lead the supervision sessions.

| Takes ownership of their own supervision by regularly attending, setting the agenda, asking key questions and focusing on their learning and wellbeing needs. | Supervisee feels more confident and sustained in their work.

|

Articulates and brings theory into practice.

| Understands the processes of reflective practice and that the ability to critically reflect on own practice is desirable.

| Clients receive client-centred professional services that are accessible, responsive, accountable, and demonstrate contemporary best practice. |

References

[1] T Morrison and J Wonnacott, Supervision: now or never – reclaiming reflective supervision in social work, 2010.

[2] R Egan, J Maidment and M Connolly, ‘Trust, power and safety in the social work supervisory relationship: results from Australian research’, Journal of Social Work Practice, 2016, 31(3): 307–321, doi: 10.1080/02650533.2016.1261279.

[3] NL Beckerman and DF Wozniak, ‘Domestic violence counselors and secondary traumatic stress (STS): a brief qualitative report and strategies for support’, Social Work in Mental Health, 2018, 16(4):470–490, doi: 10.1080/15332985.2018.1425795.

[4] Hewson and Carroll, Reflective practice in supervision.

[5] D Mandel, Worker safety and domestic violence in child welfare systems, Safe and Together Institute. n.d.

[6] Mandel, Worker safety and domestic violence in child welfare systems.

[7] Department of Health and Human Services, Human service standards evidence guide, State of Victoria, 2015, accessed 4 October 2023.

Principles underpinning best practice supervision

These guidelines are supported by an agreed set of trauma-informed principles based on the Blue Knot Foundation model. Other trauma-informed models are equally useful, such as the Sanctuary Model.[1]

In the family violence context, it can be useful to adopt a trauma- and violence-informed approach, which expands the concept to ‘account for the intersecting impacts of systemic and interpersonal violence and structural inequities on a person’s life’.[2]

Trauma and violence-informed principles can be useful in underpinning reflective supervision.[3] Especially since many supervisees and supervisors have their own lived experience of trauma, or family or sexual violence and the impacts of inequality, discrimination and marginalisation. Talking with practitioners who have not experienced trauma and who benefit from privilege about the principles and impacts of trauma and violence is equally crucial.

A trauma- and violence-informed approach also assists supervisors and supervisees to have explicit conversations about the power dynamics that may impact their relationship.

This approach aligns with the Framework for trauma-informed practice,[4] which promotes reflective supervision as a key strategy in creating trauma-informed workplaces.

Table 2: Trauma-informed principles in practice adapted from the Blue Knot Practice Guidelines[5]

| Principle | What this looks like | Reflective questions |

|---|---|---|

| Safety | Foster physical, psychological, identity and cultural safety in all interactions. | How does your organisation create safety for supervisees and supervisors? How can we create greater safety in our supervisory relationship? How can you create safer relationships with clients, colleagues and other professionals? |

| Trust | Invest in inclusive relationships that focus on mutual respect, dignity, and transparent, unbiased communication. | Does your organisation demonstrate trauma sensitivity and responsiveness at all levels of contact? How do you and your organisation convey reliability to the workforce and clients? |

| Choice | Provide freedom for supervisees and supervisors to align their approaches with their values and ethics. | How do you embed discussions about values and ethics during supervision? How does supervision provide choice for supervisees (and in turn clients) where it is available and appropriate? In what ways? |

| Collaboration | Share power and work in solidarity to support sustainability at a team, organisation, funding body and sector level. | How does your supervision style develop a sense of ‘doing with’ rather than ‘doing to’? How can you collaborate better with clients and other professionals? |

| Empowerment | Develop individual and collective strengths by acknowledging each other’s contributions and feedback or feedforward for continuous learning and reflection. | Is empowering supervisees and clients an ongoing goal of supervision and your organisation? How is this goal enabled by supervision, service systems, programs and processes? How does supervision and your organisation enable cultural empowerment? |

| Respect for inclusion and diversity | Develop an awareness that attitudes, systems and structures can interact to create inequality and exclusion. Respect diversity that includes intersecting social characteristics such as but not limited to cultural background, Aboriginality, sexual orientation, gender, gender identity, age, mental health, socioeconomic status, religion and disability. | How does supervision and your organisation convey and enact respect for workforce and client diversity in all its forms? In what ways? How does supervision and your organisation promote cultural safety? How do you know that you are practising with cultural safety and inclusion in mind? |

References

[1] Sanctuary Institute, Sanctuary model, Sanctuary Institute website, 2023, accessed 17 August 2023.

[2] CM Varcoe, CN Wathen, M Ford-Gilboe, V Smye and A Browne, VEGA briefing note on trauma- and violence-informed care, VEGA Project and PreVail Research Network, Ottawa, 2016, p 1, in Family Safety Victoria, MARAM practice guides: Foundation knowledge guide, Victoria Government website, 2021.

[3] Blue Knot Foundation, Trauma-informed services, Blue Knot website, 2019, accessed 1 March 2023.

[4] Department of Families, Fairness and Housing, Framework for trauma-informed practice, DFFH website, 2022, accessed 27 February 2023.

[5] C Kezelman and P Stavropoulos, Practice Guidelines for treatment of complex trauma and trauma informed care and service delivery, Blue Knot Foundation, 2012.

Frameworks that inform supervision

Family violence, sexual assault and child wellbeing workforces come from different theoretical backgrounds and frameworks of practice. It is important for agencies and teams to select which framework suits them best for their work and their role.

The frameworks provided are not exhaustive. They are included to describe how they might inform supervision. Further reading is provided at the end of the guidelines for more in-depth exploration of each framework.

Trauma-informed framework

Trauma-informed framework recognises that when staff feel consciously or unconsciously unsafe, the brain–body response interferes with decision-making and self-regulation.

Trauma- and violence-informed framework

A trauma- and violence-informed framework expands on the concept of trauma-informed supervision.

Attachment-based framework

Attachment-based framework incorporates an understanding of adult attachment theory and its potential impact on supervisory relationships and practice.

Strengths-based framework

A strengths-based approach is a theory that represents a ‘paradigmatic shift away from problem-focused approaches’, to focus on resilience, growth and empowerment.

Trauma-informed framework

This framework incorporates an understanding about the impacts of trauma, including vicarious and cumulative trauma on supervisees and the need for trust with their supervisor and the broader organisation. It recognises that when staff feel consciously or unconsciously unsafe, the brain–body response interferes with decision-making and self-regulation.

The aim of supervision is to reduce stress and the impacts of vicarious and cumulative trauma on supervisees. Supervision can contribute to building supervisee resilience. Trauma-informed practices, underpinned by the principles outlined above, help with these aims.

By normalising practitioner reactions to the challenges of working with traumatised people, shame is reduced. Supervisors can make a difference by acknowledging supervisee strengths and the emotional toll of the work. They can do this in a way that is compassionate, empathic and understanding, rather than blaming or pathologising.

This framework is sometimes criticised for being too individualistic, even though it includes the concept of trauma-organised cultures. This is where chronic stress and adversity leads to subtle adaptations that eventually rob an organisation of basic interpersonal safety, trust and health.[1] This includes the risk of parallel processing, whereupon the practitioners, agency and system mirror the characteristics of the traumatised ‘client’ population, such as chaos and fragmentation. This can negatively affect interpersonal dynamics when working with clients, colleagues and team culture.

Trauma-informed frameworks are often a part of a broader model (for example, the Sanctuary Model) for creating an organisational culture that can more effectively provide a ‘cohesive context’ within which healing from traumatic experiences can occur.[2] Like any cultural change process, becoming a more trauma aware, sensitive, responsive and, ultimately, informed organisation requires attention and time.[3]

References

[1] S Bloom, ‘Trauma-organised systems and parallel process’, in N Tehrani (ed), Managing trauma in the workplace: supporting practitioners and organisations, Routledge, London, 2010.

[2] A Quadara, Implementing trauma-informed systems in health settings: the WITH Study – state of knowledge paper, ANROWS website, 2015.

[3] Blue Knot Foundation, Trauma-informed services.

Trauma- and violence-informed framework

A trauma- and violence-informed framework expands on the concept of trauma-informed supervision. It considers the intersecting impacts of systemic and interpersonal violence and structural inequities of a person’s life.[1] This means that the adverse impacts of family and sexual violence trauma are understood within the broader context of patriarchal social conditions, intersectional oppression, and systemic violence and discrimination.[2]

This includes taking an intersectional view to highlight current and historical experiences of violence, so issues are not seen as originating within the person. Instead, these aspects of their life experience are seen as adaptations and consequences of trauma and violence.

To apply a trauma- and violence-informed lens to supervision, an organisation must reflect on multiple aspects of the system:

- the physical environment – where people work and meet for supervision

- supervisory relationships and team support – sense of belonging and morale

- openness to two-way communication

- the potential for parallel processes occurring – where systems inadvertently repeat the patterns clients have already experienced

- willingness to highlight instances of parallel processing ‘playing out’ in relationships

- systemic injustice and discrimination, such as racism

- responses to vicarious trauma and compassion fatigue.[3]

Supervision that incorporates a trauma- and violence-informed approach helps guard against trauma-organised systems developing. Such supervision is underpinned by the above principles and an organisation focused on:

- intending to do no harm and avoiding inadvertent re-traumatising clients and staff

- using a person-centred approach during supervision which harnesses a person’s inherent strengths, autonomy and dignity, maximising their choices and control over their lives[4]

- understanding the effects of negative stress on the brain (which can impair listening, decision making and self-regulation) and body

- understanding that behaviours during times of stress, can stem from childhood coping strategies which are no longer effective

- understanding that vicarious trauma is inevitable, but this does not mean it will necessarily cause harm

- exploring ways supervisees can use supervision, harness self and collective care, and other supports such as EAP, to reduce vicarious trauma risks

- listening to understand how supervisees make meaning of their responses to trauma, including vicarious and cumulative trauma, within the context of their own lived experience[5]

- partnering with supervisees and people who have experienced violence and sexual assault

- improving interventions with perpetrators

- surfacing vicarious resilience and compassion satisfaction

- appreciating the importance of, and incorporating, client voices, including those of children and young people

- understanding ongoing structural inequalities for our clients, including children and young people, and our workforces.

There has been criticism about the trauma discourse because it rarely names and addresses systemic injustice and racism[6] and risks pathologising trauma as an individual’s problem.[7] Trauma- and violence-informed supervision, however, includes the exploration of systemic injustice and racism. It also offers a space to explore the impact of various stressors and look for signs of vicarious resilience in the work with clients.[8]

References

[1] Varcoe et al., VEGA briefing note on trauma- and violence-informed care.

[2] Domestic Violence Victoria, Code of practice: principles and standards for specialist family violence services for victim-survivors, Safe and Equal website, 2nd edn, 2020, accessed 6 October 2023.

[3] Blue Knot Foundation, Trauma-informed services.

[4] Domestic Violence Victoria, Code of practice: principles and standards for specialist family violence services for victim-survivors.

[5] Domestic Violence Victoria Code of practice: principles and standards for specialist family violence services for victim-survivors.

[6] C Watego, Another Day in the Colony, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, 2021.

[7] V Reynolds and M McQuaid, ‘Do you have a culture of collective accountability?’, Making Positive Psychology Work podcast, 2021.

[8] Blue Knot Foundation, Supervision and practice, Blue Knot website, n.d., accessed 4 October 2023.

Attachment-based framework

This framework incorporates an understanding of adult attachment theory and its potential impact on supervisory relationships and practice. Supervisees and supervisors often show similar attachment dynamics in their close relationships as they do in the supervisory relationship.[1] The framework has been included in the Guidelines because supervision:

- is always relational

- involves some degree of vulnerability

- may be influenced by attachment dynamics[2]

- can activate the attachment patterns of both the supervisee and supervisor[3]

- fits with trauma- and violence-informed theory and practice, which incorporates attachment theory.

Alongside other factors, the experience of attachment can impact on supervisors and supervisees:

- being able to form trusting relationships

- seeking help

- being able to self-regulate

- developing resilience

- feeling burned out[4]

- becoming ‘stuck’ in unhelpful and repetitive patterns of behaviour[5]

- being effective leaders.[6]

Although the quality of supervisory relationships cannot be solely explained by attachment patterns,[7] more secure patterns have been linked to greater satisfaction with supervision.[8]

This framework can add insight into why we interact with one another and respond to stress like we do. It is not expected for supervisors and supervisees to try and determine one another’s attachment pattern. The key is to understand the strengths and challenges associated with the resulting dynamic.[9]

Understanding attachment can assist supervisors to reframe supervisee’s responses when they become anxious and overwhelmed by the work.[10] This in turn, can prevent labelling the supervisee as the ‘problem’ and a spiral into a negative feedback loop developing between the supervisor and supervisee, otherwise known as the ‘set-up-to fail’ syndrome (see section ‘When supervision becomes tricky’ on supervisor–supervisee conflict).

Like attachment, the goal of supervision is to provide a secure base for the supervisee to experiment, gain confidence, test their knowledge and skills and grow. An understanding of attachment concepts like ‘secure base’ and ‘safe haven’ helps practitioners and supervisors contain fears and anxieties and assist in keeping the supervisee regulated. Some family violence supervisors have described the importance of adopting the attachment-based ‘bigger, stronger, wiser and kinder’ approach to their role.[11] When this approach is grounded in a culture where reactions are openly discussed, and self-reflection and insight is actively encouraged, supervision can become safe, nurturing and supportive.