They are:

- Structured Professional Judgement

- person-centred approaches

- intersectional approaches

- trauma and violence–informed approaches

- safe, non-collusive practice

- reflective practice and unconscious bias

- risk management approaches.

Each practice concept in this section can be applied to working with both victim survivors and perpetrators of family violence.

However, when working with perpetrators, you should maintain a focus on the experience of victim survivors and the impact of violence caused by the person using violence.

You can do this by remembering:

- to hold the victim survivor’s experience and safety at the centre of your assessment when engaging directly with the perpetrator

- perpetrators target aspects of a victim survivor’s identity, circumstances and experiences as part of their tactics and pattern of behaviour used to coerce and control them

- each perpetrator has their own identity, circumstances and experiences that affect their choice to use violence, the risk they present to family members, and their engagement with your service.

Information contained throughout the remainder of this Foundation Knowledge Guide will vary in language from the general ‘professionals’ to the specific ‘you’.

This information applies to all professionals, and you should consider the information as addressing you when either term is used.

10.1 Structured Professional Judgement

Using the practice model of Structured Professional Judgement allows you to assess information and determine the level or seriousness of risk to the victim survivor.

As a professional, you bring your experience, skills and knowledge to the risk assessment process to make an assessment.

10.1.1 Applying Structured Professional Judgement

When working with victim survivors, risk assessment relies on you or another professional ascertaining:

- a victim survivor’s self-assessment of their level of risk, fear and safety

- the evidence-based risk factors that are present.

You can gather information to inform this approach from a variety of sources, including:

- interviewing or ‘assessing’ the victim survivor directly or, where it is your role to do so, observing or assessing the perpetrator’s narratives, behaviours and their individual context and circumstances

- reviewing any information held by your organisation about the victim survivor or perpetrator

- requesting or sharing information, as authorised under applicable legislative Information Sharing Schemes, with other organisations about the risk factors present or other family violence risk-relevant information about a victim or perpetrator’s circumstances.

You should consider this information and apply your professional judgement to each of the elements. This is the act of you analysing and interpreting information to determine the level of risk.

Assessing risk

Risk assessment is a point-in-time assessment of the level of risk. Risk is dynamic and can change over time. This means you should regularly review risk, and any changes should inform future assessment and risk management.

Your assessment of the level of risk, as well as appropriate risk management actions and approaches, must be informed by an intersectional analysis.

You should also consider relevant information about a victim survivor or perpetrator’s circumstances.

Best-practice approaches to risk assessment with a victim survivor enables them to share their story with you by you believing them about:

- their experience of violence

- the relationship

- how this has affected any children in the family (that is, understanding the risk experienced by children as victim survivors in their own right, which may also be informed by direct assessment of children)

- patterns of beliefs, attitudes, beliefs and behaviours of the perpetrator.

Evidence shows that adult victim survivors are often good predictors of their own level of safety and risk, and that this is the most accurate assessment of their level of risk.

By taking a person or victim-centred approach to risk assessment and management – listening to, partnering with and believing the victim survivor – you can recognise the victim survivor as experts in their own safety, with intimate knowledge of their lived experience of violence.

Sections 10.2 provides further detail on a victim-centred approach and applying an intersectional lens to family violence risk assessment and risk management.

10.1.2 Using Structured Professional Judgement with perpetrators

When you use Structured Professional Judgement when working with perpetrators, you must continue to centre the experience of the adult or child victim survivor. This is the case even when you do not work directly with the victim survivor to hear their own assessment of their level of risk.

When working directly with perpetrators, the practice of Structured Professional Judgement requires the following:

- Always centre the lived experience and risk to the victim survivor during your assessment by:

- observing behaviours or narratives disclosing family violence towards the adult or child victim survivors, and about the recent/current situation

- identifying overt and subtle violence-supporting narratives that indicate the person’s beliefs and attitudes about rigid gender roles, entitlement, power and control in relationships, expectations about women and partners (generally), and children and service involvement

- using your understanding of the impact of family violence in relation to any risk-relevant information disclosed or identified family violence behaviours. Remember that perpetrators will selectively disclose, if at all. They may disclose by way of seeking you to collude with their minimising, justifying or denying responsibility for their actions or behaviours

- seeking information from other services[35] to ascertain the victim survivors’ self-assessment of risk to inform your assessment. Where this is not possible, you will need to rely on your understanding of the impacts of family violence to inform your assessment.

- Identify the evidence-based risk factors present – it is likely risk is higher than indicated by any disclosure by the perpetrator or observed signs and narratives.

- Request or share information, as authorised, about the risk factors present, observations and signs, or other relevant information about a perpetrator’s risk and presenting needs and circumstances, to enable effective risk assessment and management.

- Apply intersectional analysis and your professional judgement throughout your assessment by:

- identifying if a perpetrator’s use of violence is patterned and targeting coercive controlling behaviours towards a victim’s identity or lived experience

- assessing, reflecting and seeking to understand the perpetrator’s presentation and narrative in the context of their own identity and lived experience

- identifying if there are structural inequalities or barriers to the perpetrator’s engagement with you, and whether they can name, disclose or understand what constitutes violent behaviours.

Structured Professional Judgement: what’s new?

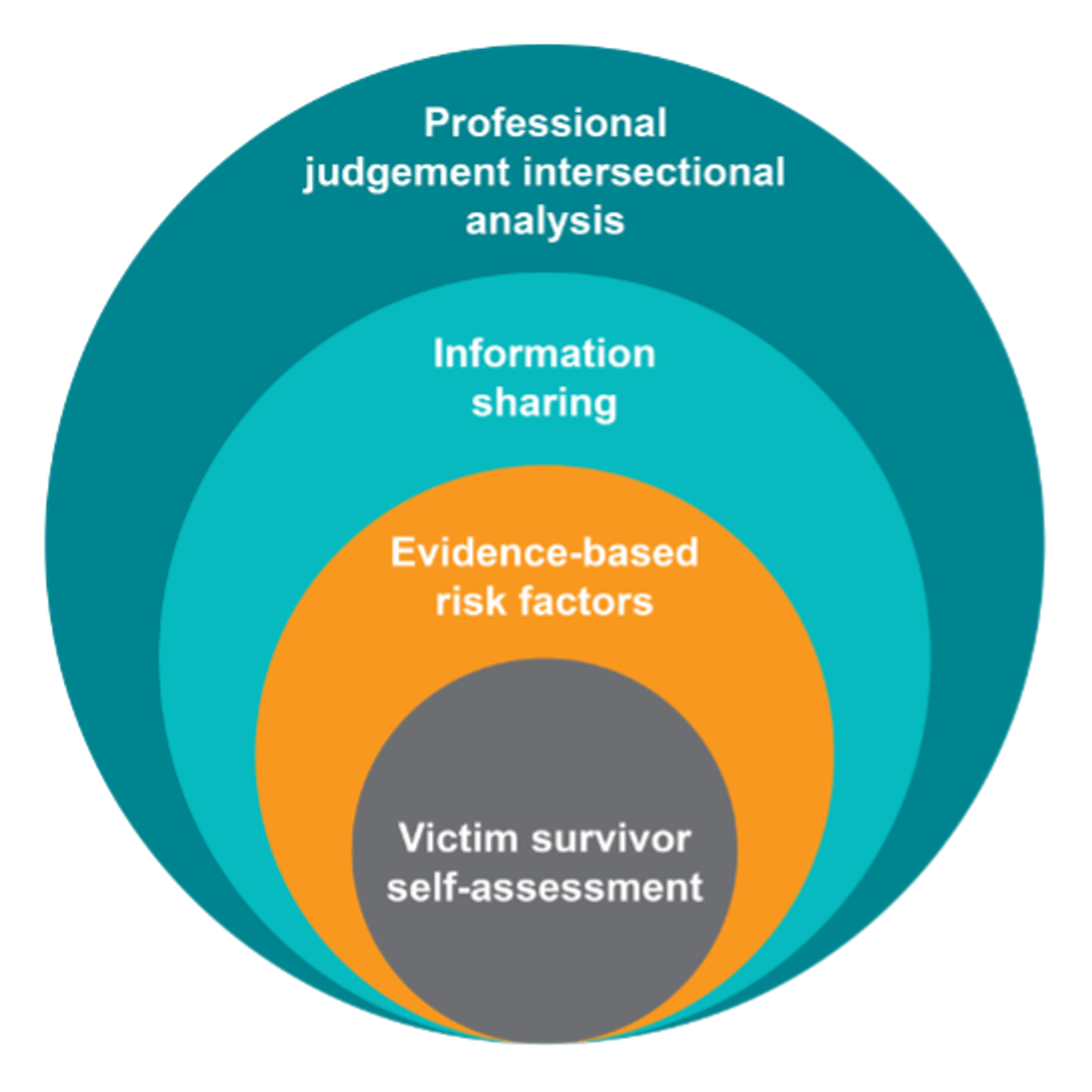

The practice model of Structured Professional Judgement in the CRAF included victim survivor self-assessment, evidence-based risk factors and professional judgement. The MARAM Framework builds on this model and incorporates the new elements of information sharing and intersectional analysis. The model is applied when working directly with both victim survivors and perpetrators of violence.

10.2 Person-centred approaches

Using a person-centred approach can help you understand the profound impact violence has on adult and child victim survivors.

This approach gives the person space to describe the violence they have experienced, allowing you to sensitively identify presenting and cumulative risk and trauma.

As well as understanding their experience of family violence, you should also identify other factors in the victim survivor’s life that may create barriers or increased risk.

A person-centred approach combines intersectional analysis and trauma-informed practice, allowing you to:

- validate experiences of violence and its ongoing impacts

- be aware of the person’s experience of barriers, structural inequality and discrimination that may be co-occurring, which may also cause or exacerbate existing trauma.

You will then be able to tailor your responses to empower victim survivors to make informed choices and access services and supports they need.

10.2.1 Person-centred approaches with victim survivors

Your approach to engaging with victim survivors (adults and children) should be informed by the:

- person’s experience of family violence

- impact of the perpetrator’s violence on victim survivors’ daily functioning and relationships

- presence of any serious threat/risk

- person’s description of their relationship with the perpetrator

- person’s relationship with other family members (who might also be victim survivors or using violence), as well as other significant family relationships.

Remember that victim survivors will have a variety of views regarding their experience of violence from the perpetrator, as well as their own risk, safety and support needs.

They may also feel ashamed or afraid to disclose their experiences of violence. Their views may change over the course of your engagement and assessment with them.

Your support and assessment should align with the victim survivor’s own assessment of their risk, safety and support needs, where possible.

However, there may be times when, as a professional, you need to take action that does not align with a victim survivor’s views and wishes regarding support and interventions.

In some cases, different family members may assess their risk to be at different levels.

An adult victim survivor may minimise risk if they are afraid the perpetrator may use further violence following an intervention, or that a child may be removed from the home. Similarly, a child or young person may also hold views and wishes that cannot be acted on for legal or safety reasons.

In all cases, it is important to be transparent, where safe, appropriate and reasonable, with both adult and child victim survivors about the decisions you make and actions you take in relation to family violence risk and safety.

For all victim survivors, approaches should respond to a person's abilities and capacity to communicate so that they can make informed choices and provide input into the risk assessment and management process.

This is especially important when your professional or service response goes against the views and wishes of the victim survivor.

Using a person-centred approach means providing adequate, transparent information to victim survivors.

For children and young people, this should be appropriate to their age and developmental stage.

Before undertaking a risk assessment, you should give all service users information about your information sharing authorisation, discussed in the victim survivor and perpetrator-focused Responsibility 6.

When working with perpetrators you are not required to provide them with information that could increase risk to adult or child victim survivors.

10.2.2 Using a ‘person in their context’ approach with perpetrators

The key concepts of practice (person-centred, trauma-informed and intersectional analysis) are also relevant to working with people using family violence. However, when applying these approaches to working with perpetrators, it is essential to maintain a victim-centred lens.

Many aspects of a person-centred approach are applicable to working perpetrators of family violence. Developing trust and rapport is critical to maintaining engagement with perpetrators, to respond to their presenting needs and circumstances and address their use of violence.

However, throughout your engagement, you must maintain a victim-centred lens and prioritise the views, needs and safety of victim survivors.

A ‘person in their context’ approach uses aspects of person-centred practice with perpetrators.

It identifies and takes into consideration the perpetrator’s presenting needs, history and experiences, risks, strengths and environmental contexts or circumstances. It helps to build an understanding of the person’s life experiences that inform their interactions and relationships with friends, family, community, services and society. This includes the values, norms and beliefs that shape their views and expectations. These are expressed in their narratives about their role and relationships, likelihood of continued violence and/or escalation over time, and barriers to personal accountability, safety and change.

In this way, considering the ‘person in their context’ can include the:

- person’s experience of family violence as a child, in other family or previous relationships

- person’s use of violence in previous relationships

- impact of their use of violence on victim survivors’ and their own daily functioning and relationships, including their parenting role

- presence of any serious threat/risk to the victim survivor, themselves or another person

- person’s description of their relationship with the victim survivor

- person’s relationship with other family members (who might also be victim survivors or using violence), as well as other significant family relationships

- person’s relationship with social, cultural and community networks

- presence of and relationship with professionals, services and systems

- any environmental factors that impact on their life.

Situating the ‘person in their context’ is an important starting point for your engagement with people you know or suspect are using family violence.

This includes developing an awareness and understanding of the:

- multiple ways that power is used and experienced within personal, family, community relationships and society broadly

- dynamics associated with the service user’s behaviour towards others

- issues affecting their circumstances, health, wellbeing and needs

- protective or stabilising factors that minimise likelihood of harm to self and risk to others.

Remember that people who use family violence are not a homogenous group.

They will have a range of identities and variety of lived experiences that have shaped their historical and current behaviours, impact on their level of risk, and influence their capacity and willingness to change.

This contextual information informs your professional judgement, assists you to identify the person’s needs, as well as those of adult and child victim survivors, and contributes to risk management activities.

10.3 Intersectional approaches

Both victim survivors and perpetrators of family violence may experience intersecting forms of power and privilege, or discrimination and disadvantage.

Intersectionality, or intersectional analysis, is a theoretical approach recognising the interconnected nature of social categorisations and identities with experiences of structural oppression, discrimination and disadvantage. [36]

The theory of intersectionality can help you to understand and examine power, privilege and oppression, and how these overlap or intersect in people’s lives to reinforce and produce power hierarchies.

Many people’s experience is shaped by multiple identities, circumstances or situations. Applying an intersectional lens means considering a person’s whole, multi-layered identity and life experience to understand the ways in which they have, and may continue to, experience inequality and oppression.[37]

This can shape a person’s experience of the impact of family violence, the nature of a perpetrator’s violent and controlling behaviours and access to services.

For example, if an Aboriginal person also identifies that they have a disability, you should respond in your risk assessment and management practice to address any combined associated barriers. This provides a respectful, safe and tailored approach (also refer to the victim survivor and perpetrator-focused Responsibility 1).

In this guide, intersectional analysis reflects an individual’s age, gender identity, sexual orientation, ethnicity, cultural background, language, religion, visa status, class, socioeconomic status, ability (including physical, neurological, cognitive, sensory, intellectual or psychosocial impairment and/or disability) or geographic location.

Gender and the drivers of family violence are critical to informing your understanding of intersectional analysis in the family violence practice context.

Structural inequality and discrimination create and amplify barriers and risk, which continue to exacerbate systemic marginalisation, power imbalance and social inequality.

Your organisation’s policies, practices and procedures can either address these inequalities, or contribute to them further by privileging the dominant group and reinforcing the exclusion of people outside of it.

People and communities experience structural inequality, barriers and discrimination as oppression and domination. These relate to the impacts of patriarchy, colonisation and dispossession, racism, ableism, ageism, biphobia, homophobia and transphobia.

When applying an intersectional lens, you must reflect on and understand your own bias, so you can respond safely and appropriately in practice. You can use supervision with managers and engagement with colleagues to reflect on and respond to bias.

The MARAM Practice Guides provide extensive information about applying an intersectional analysis lens to working with both victim survivors and perpetrators.

10.3.1 Applying an intersectional lens

Experiences of structural inequality, barriers or discrimination can alter the way family violence is:

- experienced by individual victim survivors who identify as belonging to a community or communities

- perpetrated by people using violence who identify as belonging to a community, or from perpetrators outside of the community who are using violence against an individual who identifies as belonging to a community.

Using an intersectional approach with victim survivors

In many instances, these factors contribute to increased risk and amplify barriers to disclosure, service access and engagement.

Applying an intersectional analysis lens allows you to explore the impacts of systemic and interpersonal discrimination and disadvantage on marginalised groups.

This can influence how victim survivors:

- talk about, recognise and understand their experience of family violence by the perpetrator

- understand their options or decisions about what services to access based on actual or perceived barriers. This may be due to past discrimination or inadequate service responses from the service system, including from institutional or statutory services

- describe and/or are differently impacted by their experience of family violence by the perpetrator, and violence generally.

You should reflect on your own practice and biases in considering how Aboriginal people or people from culturally diverse communities or at-risk age groups may experience barriers, discrimination and inequality.

You should also consider where you can improve and tailor your practice approach to:

- improve people’s access to resources or services, such as support to respond to family violence risk

- increase the social and economic power service users hold

- counteract the perceived negative self-worth and marginalisation of some groups, which may increase the probability of violence being used against them.

Using an intersectional approach with perpetrators

Intersectional analysis can also help you understand perpetrators’ uses of violence against child and adult victim survivors, including how they:

- engage with the service system and seek help – based on actual or perceived barriers due to discrimination, inadequate service responses, negative beliefs about help-seeking (often associated with masculine identity)

- disclose and talk about their use of family violence – including how they understand, minimise, justify, or rationalise their use of violence

- engage in personal accountability and change – for example, motivations to change and perceptions of how accountability may present in particular ways for people from Aboriginal and diverse communities. This may be due to their particular identity, experience and place in relation to the community

- become ready or motivated to change, given any complex needs as well as internal and external motivators or barriers.

10.3.2 Professional reflection

To address potential barriers, person-centred practice uses an intersectional lens and adopts culturally sensitive and safe practices when undertaking risk assessment and management.

Professionals can also collaborate with organisations that specialise in supporting communities, to provide responsive and appropriate services (also refer to Responsibilities 5 and 6).

All family violence involves a perpetrator using patterns of coercive and controlling behaviours against one or more victim survivors.

Patterns of family violence behaviours can be recognised as manifesting in particular targeted ways when used against Aboriginal people, those from diverse communities and children, young people and older people.

The identities and experiences of both the victim survivor/s and the perpetrator inform the perpetrator’s choices to use coercive, controlling and violent behaviour.

These behaviours often target the identity or perceived ‘vulnerability’ of the victim survivor. This includes exploiting the victim survivor’s experience of structural inequality, barriers or discrimination.

For example, victim survivors who are Aboriginal or belong to a diverse community or at-risk age group, such as children, young people and older people, may be reluctant to report or engage with professionals or services about their experience of violence.

Aboriginal people may be reluctant to engage because services are not, or have not been, accessible, safe or responsive to their needs.

In particular, Aboriginal women or women from diverse communities are affected by multiple barriers, structural inequalities and discrimination. Their experiences of violence have historically been dismissed, minimised or ignored.

This means they have real and perceived barriers to engagement. These experiences can also lead to trauma, affecting an individual’s presentation, needs and ability to engage with services in different ways.

People who use family violence can concurrently experience power and privilege, and disadvantage and marginalisation.

Intersectional analysis allows us to understand that some people enjoy greater privileges than others.

For example, white, heterosexual, able-bodied, cisgender men typically enjoy greater social, political and economic status than people who do not reflect these characteristics.

Many people who use family violence benefit from the effects of patriarchy, colonisation and dispossession, racism, ableism, ageism, biphobia, homophobia and transphobia.

They may choose to enact oppressive structures of power and control in their own families, while also experiencing oppression and powerlessness in other contexts.

Men who do not hold some of those attributes may still be privileged over women by virtue of their gender but may feel or experience being subordinate to the dominant masculine ‘ideal’ because of their race, religion, ethnicity, citizenship status or ability.

Research has documented the ways in which men from diverse communities have been stereotyped to create a hierarchy of masculinity.

For example, on a spectrum, some groups of men are consistently ‘feminised’, including gay-identifying men, men with disabilities, some men of Asian heritage and/or appearance, while working class and men of African descent have been represented as ‘too masculine’ or too overtly physical (while still being marginalised).[38]

This can play out in the forms of community and family violence they may experience (predominantly) from other men, and in their experience of structural inequality, barriers and discrimination in the community more broadly.

It is the responsibility of professionals and services to reduce and remove structural inequalities and barriers to engagement, not the responsibility of the service user.

You should also recognise the collective strengths and the social, cultural and historic contexts of Aboriginal people and people from diverse communities.

The concept of intersectionality informs much of this Foundation Knowledge Guide and both the victim survivor and perpetrator-focused MARAM Practice Guides.

In particular, Section 12, ‘Presentations of family violence in different relationships and communities’ considers each community using this intersectional lens.

10.4 Trauma and violence–informed practice

Trauma is defined as the experience and effects of overwhelming stress that result in a reduced ability to cope or integrate ideas or emotions that are the result of that experience.[39]

Trauma arises from activation of instinctive survival response to threats.[40]

It can occur through everyday events outside a person’s control (loss of housing or employment), exposure to vicarious trauma, collective trauma (such as large-scale emergencies, natural disasters, war, acts of terror), systemic violence (including institutions), interpersonal violence, neglect and abuse during childhood or adulthood (such as from an intimate partner, caregiver or known person/family member and stranger violence), and historical and intergenerational trauma.[41]

Complex trauma can result from repetitive, prolonged and cumulative violence. Complex trauma is often interpersonal, intentional, extreme, ongoing and can be particularly damaging when it occurs in childhood.[42]

Trauma for children may be identified as adverse childhood experiences, which typically include physical, sexual and emotional abuse, physical and emotional neglect or witnessing family violence as a child.[43]

Trauma and violence–informed practice considers ‘the intersecting impacts of systemic and interpersonal violence and structural inequities on a person’s life’.[44]

This includes using intersectional analysis to highlight current and historical experiences of violence so that symptoms are not understood as exclusively originating within the person. Instead, these aspects of their life experience are viewed as adaptations and predictable consequences of trauma and violence.[45]

10.4.1 Impacts of family violence trauma on victim survivors

Having a trauma-informed lens is essential when engaging in family violence risk assessment and management when working with victim survivors.

Key practice considerations include the following:

- Everyone experiences some level of trauma from family violence.

- Trauma affects each person differently.

Trauma and violence–informed services do not necessarily treat trauma, but instead work to ensure the service experience will not cause further trauma, harm or distress.

This includes providing safe environments for disclosure and understanding the effects of trauma. It also includes being able to recognise ‘symptoms’ and problems as coping mechanisms that may have initially been protective.[46]

Coping mechanisms may be resourceful and creative attempts to ‘survive adversity and overwhelming circumstances’.[47]

At all times, view behaviour as an adaptive response to challenging life experiences. All your interactions with service users should be respectful, empathic, non-judgemental and convey optimism.[48]

In the context of victim survivors’ experiences of family violence from a perpetrator, trauma can result from physical, emotional, psychological, spiritual and sexual abuse, neglect and witnessing of violence or its impacts.

It can result from a one-off event, a series of or enduring events, or from intergenerational trauma resulting from the impacts of violence or abuse in a family or community.

Trauma is inherent to victim survivors’ experience of family violence.

It is the result of events outside of a victim survivor's control. These events may be unexpected, and the person may be unable to stop them, as they have no control over the perpetrator’s choice to use violence.

It is not the event that determines if trauma will occur, but rather the person’s experience of it and the meaning they make of it.

This can also be shaped by a person’s developmental age and stage, their cultural or personal beliefs and/or the support available to them.[49]

The impact of these events is to display power differentials that position the person as powerless.[50]

Effects of trauma

The effects of trauma may be felt immediately or occur later in life.

The way trauma manifests for a victim survivor depends on a range of factors, such as the relationship with the perpetrator and whether they are believed and supported by family/friends or professionals.

Trauma can affect a person’s relationships with parents or carers, siblings or other family members, friends and social networks, as well as their housing security, and engagement in education, employment and community.

It can interrupt and change a child or young person’s development, including brain development, and is (more) likely to have long-term effects.

The impact of trauma in adulthood can manifest in different ways, and it is likely to be compounded if the person experienced childhood trauma (due to cumulative effects).

The impact of trauma on older people can be wide-ranging and will depend on their previous trauma experiences and current supports.

Trauma can have significant impacts on a victim survivor’s identity and can create feelings of shame and/or powerlessness, which may result in negative coping behaviours or avoidance.

While different people react to trauma in different ways, for some it can have lasting adverse effects on their functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional or spiritual wellbeing. Cumulative effects can manifest in many ways over a person’s lifetime.

While the effects of trauma can subside for some victim survivors once they are safe (for example, once they leave a violent relationship), this may also be when acute trauma responses commence.

A person can be ‘triggered’ by seemingly everyday events, where a person’s stress responses are activated in response to thoughts, sense activation, experience or interpersonal dynamics.

This can be experienced as a re-living of the original situation, and the person can respond from that space.

Trauma and violence survivors can be misunderstood as ‘overreacting’, when in their experience they are reacting to the trauma of the past. Their response can be both emotional and most likely also physiological (‘flight-fight-freeze’).

Children and young people who have experienced trauma have a greater likelihood of presenting with a physiological impact as a result, given their rate of neurobiological development. A child or young person’s neurobiology can become patterned to respond as if a threat is imminent even when it is not.

10.4.2 Trauma and violence–informed practice when working with Aboriginal people and communities

The disproportionate impact of family violence on Aboriginal people is deeply rooted in the intergenerational traumas endured as a result of invasion and the violent dispossession of land, culture and children.[51]

Remember

There is a gendered element to family violence for Aboriginal people, but family violence also sits within the violence of colonisation and its ongoing legacy, including the displacement of men from their traditional roles and the forced removal of children.

The ongoing legacy of these events continues to have profound impacts, including trauma and grief on Aboriginal people individually, and as families and communities. Aboriginal children continue to be removed from their families at disproportionately high rates because of the enduring impacts of intergenerational trauma, which can increase the likelihood of exposure to family violence.[52]

When working with Aboriginal people experiencing or using violence, as part of your engagement it is particularly important that you hold an understanding of trauma, including intergenerational trauma and the person’s healing journey.

You should offer the choice to engage with Aboriginal services to ensure trauma-informed approaches and cultural safety. The principles of Nargneit Birrang– Aboriginal Holistic Healing Framework for Family Violence can also guide your response.[53]

10.4.3 Locating non–family violence related trauma in your practice (intersectionality)

People from any identity or community can have experiences of collective trauma not related to family violence.

Pre-migration trauma is a contributor to perpetration of family violence against women and children in migrant and refugee communities.[54]

People from migrant and refugee backgrounds may have experiences of political violence and trauma in their home countries that have ongoing personal consequences.

They may have histories of family violence pre-dating immigration experiences and the effects of childhood experiences of violence.

Similarly, research has identified an association between men experiencing trauma in their country of origin and later perpetration of family violence. Trauma includes imprisonment, torture and involvement in conflict as a combatant and, for men, this was associated with negative mental health impacts and violent behaviours.[55]

10.4.4 Establishing a trauma and violence–informed approach with all service users

You should be aware of the signs and impacts of trauma when assessing and managing family violence risk. This is described in practice guidance for the victim survivor and perpetrator-focused MARAM Practice Guides for Responsibility 1.

For professionals who do not have mental health expertise, identifying the presence of trauma can be difficult.

Symptoms such as hypervigilance, which is commonly linked to trauma, are also often present among service users who appear resistant.

Trauma and violence–informed practice in the context of family violence is not about treating trauma conditions or symptoms – this can be supported by referral for specialist supports where it is not a part of your role.

Instead, it is about being sensitive to the impacts of trauma and ongoing structural inequality.

Applying a trauma and violence–informed approach to your work means:

- understanding the person’s experience of trauma and structural inequalities

- responding to the impacts of both on individuals, families and communities, avoiding re-traumatisation, and maximise engagement with your service.

It is important to approach all engagement with victim survivors and perpetrators[56] of family violence with a trauma and violence–informed approach.

This means:

- providing space for individuals to feel physically and psychologically safe

- seeking to build trust with service users, and as much as possible provide transparent service delivery

- modelling respectful relationships

- engaging in strengths-based ways

- supporting service users to make pro-social, non-violent choices that increase safety

- working against stereotypes and biases by using the person in their context approach.

10.4.5 Using a trauma and violence-informed approach when working with perpetrators of family violence

For people who use family violence, the impacts of trauma can be complex. Engaging with them through a trauma and violence–informed lens does not mean validating or excusing their behaviour.

Many people who use family violence have histories of adverse childhood experiences, including violence within their family.

Some people who use violence may have also experienced traumatic or violent events. This includes past and current impacts of colonisation, refugee and/or migration experiences, institutional racism, discrimination and stigmatisation, lateral violence and natural disasters.

These experiences can have severe impacts, including on physical, relational and emotional functioning, issues of emotional regulation and cognitive functioning, and diagnosed or undiagnosed mental health issues.

In some circumstances, the person’s own continued use of violence can compound their trauma responses.

When working with perpetrators, identifying trauma is important in addressing their health and wellbeing needs.

This may lead to a reduction of risk behaviours or positively contribute to engagement with services. If you are not trained in responding to trauma, you may need to refer the person to mental health services.

It is tempting within professional and therapeutic frameworks to believe that addressing perpetrators’ past and ongoing trauma will lead to attitudinal and behavioural change.

However, to be trauma-informed when assessing perpetrator risk, you must hold in balance that:

- using violence against adult and child victim survivors is a choice

- trauma can be a contributing factor in the use, change or escalation of family violence by the perpetrator if they are not being supported to take responsibility for managing it

- if unaddressed, trauma can negatively impact a perpetrator’s capacity to engage in change work.[57]

10.5 Safe, non-collusive practice

The term ‘collusion’ refers to ways that an individual, agency or system might reinforce, excuse, minimise or deny a perpetrator’s violence towards family members and/or the extent or impact of that violence.

Invitations to collude occur when the perpetrator seeks out the professional to agree with, reinforce or affirm their narrative about their use of violence, the victim survivors or their situation.

When taken up by professionals, this practice colludes with the perpetrator’s attempts to avoid responsibility for their use of violence.

10.5.1 Recognising collusion

Collusion takes many forms. Professionals collude by demonstrating compliant collusion (agreement) or through oppositional confrontation (reprimand or arguing with them).

It can be expressed with gestures implying agreement, a sympathetic smile or a laugh at a sexist or demeaning joke.

It is there when all or partial blame is laid on a victim survivor and when a perpetrator’s excuses are accepted without question.

Collusion by professionals is often unintentional.

It arises from the long-standing subjugation of women and legitimisation of various forms of violence against women and children.

It can be conscious or unconscious, and it includes any action that has the effect of reinforcing the perpetrator’s violence-supportive narratives as well as their narratives about systems and services.

Perpetrators can intentionally invite professionals to collude in their narratives. This gives the narratives legitimacy, while allowing them to avoid thinking critically about their behaviour and its impact on others.

Professionals have a responsibility to recognise invitations to collude.

This includes recognising your own discomfort when hearing perpetrators’ narratives and knowing when and how to adjust your responses to maintain the person’s engagement while holding awareness of their use of violence.

10.5.2 Effects of collusion

The effects of collusion depend on the form it takes. It can:

- strengthen the violence-supportive narratives and justifications that a perpetrator uses to excuse their use of violence

- strengthen and/or reinforce the ways that a perpetrator minimises or denies responsibility for their behaviour, thereby making it less likely they will stop their use of violence

- allow a perpetrator to call on the authority of a professional (such as a counsellor) to shore up their own position. For example, saying to a victim, ‘My counsellor agrees with me that you need to …’

- reinforce a perpetrator’s position to take an oppositional or argumentative stance that gets in the way of them taking responsibility for their behaviour

- allow a perpetrator to use the service system against family members. For example, by conveying the message that the service system is taking the perpetrator’s side and therefore that the victim’s resistance is futile.

10.5.3 Avoiding collusion

You can actively avoid collusion with a perpetrator by doing the following:

- Be aware of the ways that perpetrators invite collusion and pre-plan for the engagement.

- Consider your role and level of responsibility to directly engage with perpetrators about their use of violence, being mindful of any potential to increase risk of harm to victim survivors.

- Do not interview or ask questions of a victim survivor in the presence of a potential perpetrator or adolescent who may be using family violence. Doing so may increase the risk to victim survivors, including children.

- Reflect on your own practice and adopt a balanced approach to engagement (further information is at Responsibility 3)

- Consider sharing information or seeking secondary consultation with a specialist family violence service that can:

- support the person you suspect is experiencing family violence

- offer expertise in assessing perpetrator risk

- safely communicate with a perpetrator and engage them with appropriate interventions and services.

If you believe a person may be using violence and/or seeking your collusion with their use of violence, apply the principles of reflective practice and consult with your colleagues or consult with a specialist family violence service.

Seek ongoing professional development and refinement of skills with support of supervisors, practice leaders and specialist family violence services.

Some professionals are uniquely positioned through their engagement with perpetrators in non-specialist family violence service settings to hold information and take responsibility to support risk assessment and management of perpetrators of violence. These professionals and services can support perpetrator accountability in a range of ways.

Section 12 has more information about common perpetrator narratives in different contexts and communities. The perpetrator-focused Responsibility 1 provides more information on safe, non-collusive communication and Responsibility 3 provides more information on how to recognise invitations to collude and professional stances in practice and adopt a balanced approach to engagement.

10.6 Reflective practice and unconscious bias

Remember

Responsibility for the use of violence rests solely with the perpetrator.

Victim survivors are not to be blamed, held responsible or placed at fault (directly or as part of structural responses) for a perpetrator’s choice to use violence.

This includes shifting responsibility and accountability for violence and its impacts on children towards perpetrators, and away from adult victims’/non-violent parents’ perceived ‘failures’, such as within the concept of ‘protective parenting’.

The safety and wellbeing of children must be prioritised.

The practice of ‘tilting to the perpetrator’ should be used to hold perpetrators accountable for their ‘failure to protect’ children through their use of violence.

Professionals should work with adult victims/non-violent parents, to enhance their safety, stabilisation and capacity to also enhance the safety of children.

All decisions and judgements we make are influenced by our existing knowledge, perceptions and biases. These develop through socialisation, education and learned associations between various personal attributes, identities and social categories.

Biases are learned ideas, opinions or stereotypes formed throughout an individual’s personal and professional life through our understanding of culture, family, attitudes, values and beliefs (including religious beliefs).

Bias can occur when this experience and understanding leads to assumptions about individual people or communities based on their circumstances, personal attributes, behaviour and background. This includes characteristics such as a person’s age, gender identity, sexual orientation, ability or disability, faith, language and cultural background.

All people have these biases. As a professional, you should recognise your own biases in your approach to Structured Professional Judgement. You may be conscious or unconscious of the biases you hold.

Part of using an intersectional lens means being self-aware and thinking about how your own characteristics have shaped and informed your identity, as well as the biases you hold.

You should also reflect on your place in the service system’s creation of structural privilege and power, and how conscious or unconscious bias might affect your responses to service users. You can use supervision with managers and engagement with colleagues to reflect on and respond to bias.

Bias might relate to understandings and misconceptions about the prevalence and forms of family violence.

For example, research has shown that there continues to be a decline in the number of Australians who understand that men are more likely than women to perpetrate domestic violence. [58]

It is critical that all professionals are aware of the personal values that underpin their practice.

This includes recognising biases, judgements and assumptions that may affect service users’ engagement with services and thus inadvertently increase risk.

Practising this will support you to become aware and unpack your unconscious biases.

10.6.1 Bias in risk assessment and risk management

In the context of family violence risk assessment and risk management practice, bias can cause you to make judgements and assumptions about a person’s particular experiences or use of family violence and their level of risk.

It can also create, or fail to address, existing barriers in your engagement with service users or their engagement with other services.

Examples include:

- making assumptions about the effects of a person’s disability, such as assuming that a person with a disability that affects their communication has a cognitive or intellectual disability or presuming a person with disability does not have ‘capacity’

- minimising the experience of violence or its impacts on people with disabilities or older people if they require care and support, such as colluding with narratives of ‘carer stress’ or failing to recognise impacts due to the victim survivor's lower communication capacity

- stereotyping people from LGBTIQ communities, including by mischaracterising their experiences based on heteronormative assumptions, minimising or colluding with ‘mutualising’ language[59] or not recognising forms of family violence in LGBTIQ communities and relationships due to the dominant recognition of heterosexual intimate partner violence

- making assumptions about the experience and acceptability of family violence for people from culturally, linguistically and faith-diverse communities

- making assumptions about an older person’s universal capacity due to their age or presenting state of dependence, and/or presence of medical conditions which impact cognition such as dementia.

You should engage in reflective practice by considering how your own cultural norms and practices might manifest as conscious and unconscious biases affecting your decisions, engagement with service users and approaches to Structured Professional Judgement.

Due to the nature of unconscious bias, you may be unaware of its effects. This reflective practice should be supplemented through discussion of these issues in supervision, with colleagues with greater expertise in these areas, and/or through collaboration with services with experience and expertise in working with the community or group in question.

10.6.2 Cultural responsiveness

Cultural responsiveness means being alert to your own or other professionals’ potential biases, privileges and cultural stereotyping.

It also means you have a responsibility to educate yourself about the culture of the people you work with.

Cultures are continually evolving, and each person lives culture in their own way.

In addition to self-education, always invite people to help you understand what is culturally significant to them, individually and in their relationships with other family members. This includes parenting practices if children or young people are present.

Secondary consultation or partnership with a bi-cultural worker can help you build this understanding.

Strive to be curious and open to how culture might interact with other factors that impact on adults, children and young people.

10.6.3 Professional responsibilities, unconscious and conscious bias when working with perpetrators

It is important to remember that the role of many professionals is to engage with perpetrators so that they are in view of the service system, which supports keeping victim survivors safe.

Part of a professional’s responsibility to perpetrator accountability is ensuring that any negative views you may have about the perpetrator does not influence your direct engagement.

Enacting negative views in practice may create oppositional or confrontational engagement, which can escalate both the risk to the victim survivor and increase the likelihood that the perpetrator will disengage from your service and/or the system whose responsibility it is to keep them in view.

Recognising conscious and unconscious bias is described in perpetrator-focused Responsibility 1. Reflecting on your own practice to identify balanced, oppositional confrontation and compliant collusive approaches is described in perpetrator-focused Responsibility 3.

10.7 Risk management

Risk management should focus on the safety of victim survivors and actions that keep perpetrators in view and hold them accountable for their behaviours.

This includes actions to assist with:

- risk management and safety planning with adult and child victim survivors, including being responsive to immediate risk when violence is occurring, and supporting them to stabilise, move forward and recover from the violence they have experienced

- risk management interventions directly designed to reduce or remove perpetrators’ risk, support them to stabilise their needs and circumstances that relate to risk behaviours, take responsibility for their use of violence and support their capacity to make choices to stop using violence

- coordinating and collaborating across services to share information and plan risk management actions to keep victim survivors safe and perpetrators in view and accountable.

All prescribed organisations have some role in risk management matched to their responsibilities under the MARAM Framework.

10.7.1 Risk management responses and actions

Risk management is the intervention required to prevent or reduce the likelihood of future risk and respond to impacts of family violence that has occurred.

Risk management responses should be person or victim-centred and trauma-informed in their development, to ensure they are holistic and respond to a victim survivor’s needs and can promote stabilisation and recovery.

All risk management is based on risk assessment. It responds to the level of risk caused by the perpetrator’s use of violence and coercive control, including patterns and forms of violence that may target a victim survivor’s identity or experience of structural inequality, barriers or discrimination.

Actions that comprise risk management often include information sharing, secondary consultation and/or referral, coordinated and collaborative practice, risk management planning of perpetrator responses and interventions, safety planning directly with victim survivors and perpetrators and ongoing case management.

Risk management strategies that target a perpetrator’s behaviour include responding to their presenting needs and circumstances, without collusion, and identifying, understanding and managing their pattern of family violence over time.

This can include direct intervention to lessen or prevent further violence from occurring, responding to:

- current risk behaviours with interventions to increase accountability, and

- presenting needs and circumstances related to escalation of risk by coordinating with a range of police, justice, specialist family violence (perpetrator and victim) services, and other interventions.

10.7.2 Safety planning

Safety planning is one part of risk management. It typically involves a plan developed by a professional in partnership with the victim survivor or perpetrator.

When working with victim survivors, safety planning aims to:

- help manage their own safety in the short to medium term

- build on what the victim survivor is already doing to resist control, manage the impacts of the perpetrator’s behaviour and other actions aimed at keeping themselves safe.

When working with perpetrators, safety planning aims to:

- encourage them to take responsibility for their needs and circumstances that relate to escalating family violence risk behaviours

- stop their use of coercive, controlling and violent behaviours against family members, including through de-escalation strategies

- promote self-initiating engagement with professional services when their circumstances change or use of risk behaviours escalates (risk to self (suicide or self-harm) or risk to victim survivors).

Safety planning strengthens key ‘protective factors’ that promote safety, stabilisation and recovery. These include factors such as intervention orders, housing stability and safety, health responses, support networks, financial resources and responding to wellbeing and needs.

Where possible, safety planning with a perpetrator must take into account any safety plans in place for victim survivors.

Safety planning often requires a collaborative approach and information sharing with services working with:

- adult victim survivors

- children and young people who are victim survivors. This includes:

- within an adult victim survivor’s safety plan, with responses to each child’s risk and needs, and

- older children who may have their own safety plan with their input, where safe, appropriate and reasonable. This helps them identify with whom and where they feel safe, whom they can talk to and what actions they can take (such as calling police)

- adult perpetrators – with professionals separately considering any safety plans for adult and child victim survivors in context

- other family members or carers (who are not using violence).

10.7.3 Information sharing as risk management

The victim-survivor and perpetrator-focused MARAM Practice Guides for Responsibilities 2, 4, 6 and8 provide guidance on risk management at different levels of practice (identification, intermediate and comprehensive).

This includes safety planning, information sharing, secondary consultation and referral, coordinated and collaborative practice.

This guidance also covers how to manage risk for both adult and child victim survivors, and adult perpetrators.

The risk management actions that a professional or service should take to reduce or prevent the family violence risk behaviours of a perpetrator will vary according to roles and responsibilities.

In addition to the above, this may include:

- providing consistent community-level information and messages that violence will not be tolerated or accepted

- recognising invitations to collude with a perpetrator’s minimising or victim-blaming narratives

- assisting victim survivors to report family violence that is a criminal offence to police

- contributing to the monitoring of a perpetrator’s use of violence and sharing information with relevant organisations

- being responsive to the perpetrator’s presenting needs and circumstances, without collusion, and supporting service responses that address issues linked to family violence risk behaviours

- contributing to collaborative multiagency actions that are designed to increase safety for the victim survivor, for example, planning appointment times that reduce the likelihood of the perpetrator being aware of actions the victim survivor is taking to leave the home or attend an appointment

- safety planning directly with the perpetrator.

10.7.4 Worker safety

Interventions with perpetrators may increase risk to victim survivors and others within the community, including professionals.

All professionals must be mindful of policies and procedures for working with vulnerable service users, both within agency buildings and when conducting home visits or outreach activities.

At all times, you should have opportunities in the workplace to engage in reflective practice and supervision to explore both perceived and real risks to your own safety.

In planning with your supervisor, determine opportunities for support for yourself, ways to manage risks to you and your service users, and alternative arrangements to support the engagement and monitoring of the person using violence.

Further information on worker safety is in Workplace Support Plan in the Organisation Embedding Guidance and Resources.

Updated