Download and print the PDF or read the accessible version:

Note

Only professionals and services who are trained are required to provide a service response to people using or suspected to be using family violence related to their use of violence.

The advice in this practice guide is for professionals in non-specialist services who may suspect or know a service user is using family violence.

The learning objective for Responsibility 1 builds on the material in the Foundation Knowledge Guide.

1.1. Overview

This guide supports you to create respectful, sensitive and safe engagement with people you know or suspect are using family violence.

This includes:

- keeping victim survivors and their lived experience at the centre of all risk identification and assessment

- using trauma and violence-informed principles in your practice

- recognising common presentations of people who use violence

- being aware of risks the person presents to victim survivors, as outlined in the Foundation Knowledge Guide

- maintaining professional curiosity and a non-judgemental stance when engaging with people using violence.

This guide builds on concepts in the Foundation Knowledge Guide.

When you engage with a person using violence in a respectful, sensitive and safe way, you support disclosure, facilitate identification and keep them in view of the system.

Responsibility 2 includes more information on identification of family violence risk.

Your organisation will also have its own policies, practices and procedures relevant to safe engagement, including worker safety.

Leaders in your organisation should support you and your colleagues to understand and implement these policies, practices and procedures.

Key capabilities

All professionals should use Responsibility 1, which includes understanding:

- the gendered nature and dynamics of family violence (covered in the Foundation Knowledge Guide and the MARAM Framework)

- respectful, sensitive and safe engagement as part of Structured Professional Judgement

- how to facilitate an accessible, culturally responsive environment for safe disclosure of information

- how to prioritise the safety and needs of victim survivors when engaging with a person who uses violence

- how to tailor safe engagement with Aboriginal people and people from diverse communities

- the importance of using a person in their context approach

- recognising and addressing barriers that impact a person’s help-seeking for their use of violence and the safety of their family members

- safe engagement to build rapport and avoid collusion with people you suspect or know are using family violence.

1.2. Engaging with people who use family violence

1.2.1. Engagement as part of Structured Professional Judgement

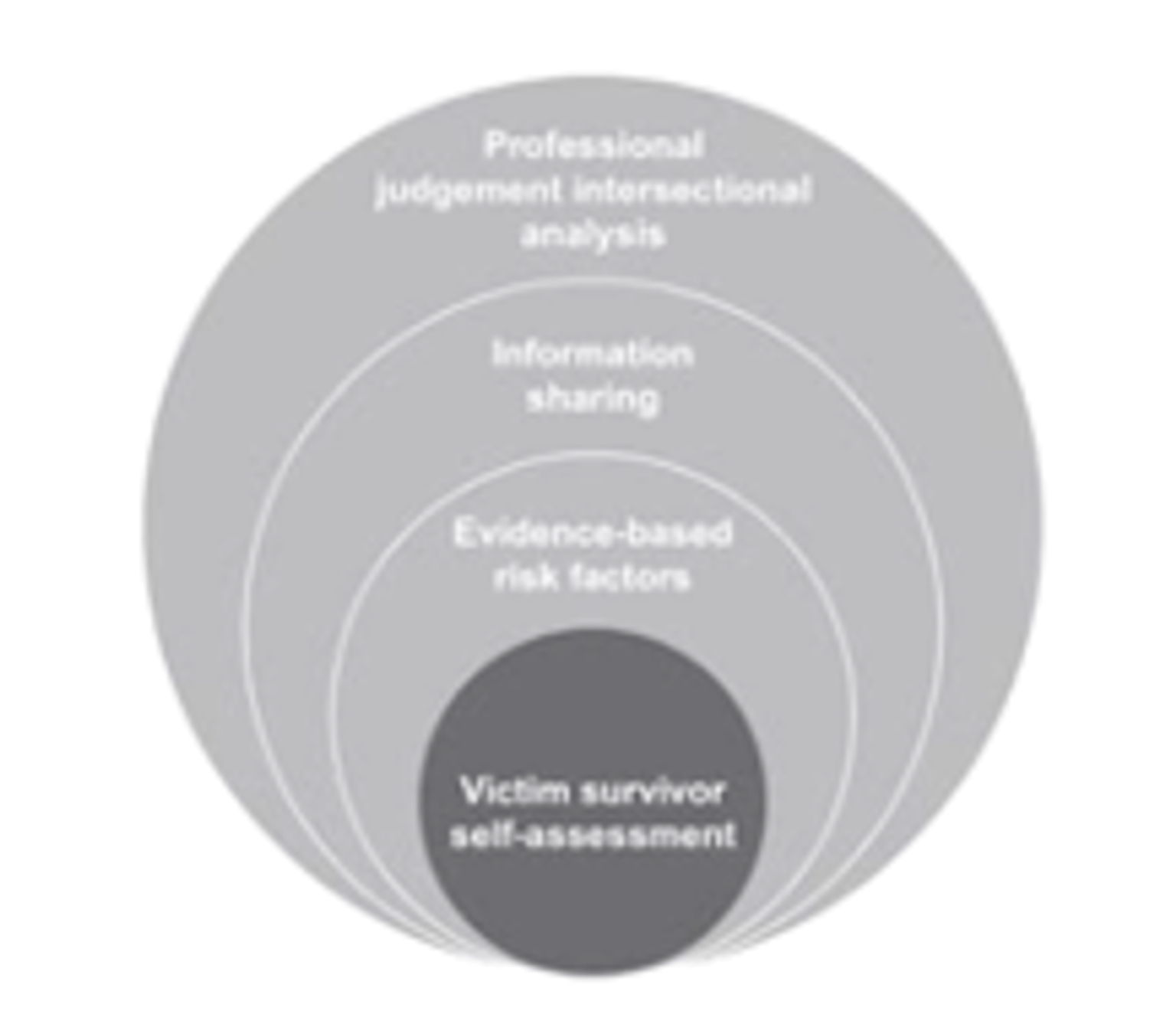

Reflect on the model of Structured Professional Judgement, outlined in section 10.1 of the Foundation Knowledge Guide and in Figure 1 below, when working with people you suspect or know are using family violence.

Using this model supports you to put the victim survivor self-assessment of risk and their experience at the centre of your engagement with the person using violence.

Engaging with people who use violence helps to keep victim survivors safe.

It keeps people who use violence in view of the system and enables professionals to support them to address their needs, circumstances and behaviours that relate to family violence risk, which reduces risk for victim survivors.

Respectful, sensitive and safe engagement allows you to build rapport with people you suspect or know are using family violence. This increases the likelihood they will disclose their use of family violence.

Through safe engagement, you can observe behaviours and narratives that indicate likely use of family violence. Engagement also increases the chances the person will directly disclose evidence-based risk factors (discussed in Responsibility 2).

Further information about Structured Professional Judgement will be provided in each of the relevant chapters of the Responsibilities for Practice Guide.

1.2.2. Creating a safe and respectful environment to engage

Remember

Professionals work with people who may be using family violence in many ways. If you do not have a specialist family violence role, your engagement with the person should aim to:

obtain and share information that builds a complete view of the person’s presenting needs and circumstances that may be linked to use of family violence

not increase the risk the service user presents to adult and child victim survivor/s, themselves or others.

To create an environment where the person feels safe and respected to talk about their needs, circumstances and family violence behaviour, consider:

- the immediate health and safety needs of each person, including each person experiencing violence (adult or child) and the person using family violence

- the physical environment, including accessibility

- communicating effectively

- safely and respectfully responding to the person’s culture and identity

- asking about identity and giving people the choice to engage with a service that specialises in working with Aboriginal communities or diverse communities

- undertaking cultural awareness training and connecting with local supports for advice and referral.

1.2.3. Why we use safe engagement with people using violence

Safe engagement with service users is a universal obligation of all professionals. This contributes directly to victim survivor safety by:

- keeping people using or suspected to be using family violence in view of the service system

- identifying and managing family violence risk

- improving capacity of a person using violence to change their behaviour.

Many of the skills and practices you already use will contribute to creating a safe and respectful environment for people who may be using family violence.

It is likely you already use trauma and violence-informed approaches, and you may have protocols for welcoming service users into your service in ways that reduce the likelihood of re-traumatisation.

These types of protocols create safety for all service users, including people you suspect or know are using family violence.

Safety in the context of working with Aboriginal people and people from diverse communities involves using culturally safe practices, including offering referrals to culturally appropriate supports and organisations.

You should also use secondary consultation with Aboriginal community or culturally specific services to ensure you are providing culturally safe responses.

1.2.4. Non-engagement and disengagement

Some service users may not engage with or disengage from the service system over time. These terms refer to:

- non-engagement – this is when you have been unable to engage or had minimal contact with a service user

- disengagement – this is when a service has commenced, but the service user does not continue, withdraws, misses appointments, rejects the service or engagement you are offering, or rejects what has been said to them. For example, people using family violence will often disengage when the crisis subsides and will minimise, deny or justify what has occurred.

Both outcomes provide information for your understanding and analysis of the service user’s context and family violence risk.

Be aware of your personal biases when you determine whether a service user is open to engaging, is experiencing a barrier to engagement, is not engaging or has disengaged.

1.2.5. Limited confidentiality statement

During initial engagement, you should make sure the person understands how their privacy is managed in your service, including how you will protect, use and share their information as authorised under law.

Where a person is engaging with your service and you know or suspect they are using family violence, your service should have a clear limited confidentiality statement covering the ways their information can be shared without their consent. This includes assessing or managing family violence risk under the Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme, or as otherwise required under law where there is a risk to themselves or others.

You do not need to re-confirm their understanding of this statement before or after making a request or sharing information under the Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme or the Child Information Sharing Scheme.[1]

Sensitive, clear and transparent engagement is important to keep the person who may be using violence engaged with your service and the broader service system.

Refusal or reluctance from a service user to agree to participate in your service with an understanding of limited confidentiality and authorised information sharing may indicate current or future family violence risk and must be recorded (See Responsibilities 2, 3 and 7).

Responsibility 6 has further guidance on information sharing and the ‘limited confidentiality’ conversation.

1.3. Prioritising immediate health and safety

Your first priority is to establish whether a service user presents an imminent risk to adult or child victim survivors, themselves, third parties or professionals.

If there is an immediate risk, contact:

- the police or ambulance by calling ‘triple zero’ (000), and/or

- other emergency or crisis service for assistance.

Assessing immediate safety includes:

- Identifying that a threat is present, such as from disclosure by a victim survivor or the person using violence, or information provided by another agency. This can apply to people known to be using family violence and people who do not have a known history of family violence

- Identifying whether the threat is an immediate threat, including situations where the service user has made a specific threat to a victim survivor, themselves, a third party or a professional and is able to access them to carry out the threat

- Determining the likelihood and consequence if immediate action is not taken to lessen or prevent that threat.

Actions to respond to an immediate threat may include:

- calling police or emergency services if required (as above)

- facilitating or encouraging access to medical treatment if you are aware the victim survivor or person using violence has sustained injuries or appears otherwise unwell. This may include if the service user does not present an immediate threat to others but requires immediate intervention for their own safety and wellbeing, such as being drug affected or experiencing an acute mental health crisis. Follow your organisation’s procedures for establishing safety

- using Section 3.10 and Appendix 6 in Responsibility 3 to identify common suicide, self-harm and family violence risk factors.

Responsibility 2 has further guidance on determining the immediate risk to safety a person using family violence may present to adult and child victim survivors, other family members, themselves or third parties.

Your service or organisation should have established policies and processes to manage an immediate threat. These may include calling security or other suitable personnel.

It may not be appropriate, safe or reasonable to engage further with the person causing the immediate threat until safety risks or health needs are addressed.

1.4. Physical environment

The physical environment sets the context for establishing and maintaining rapport. This underpins effective risk identification, assessment and management.

You can create a safe environment by:

- making the service user feel welcome, that their cultural safety is important and that their identity will be respected (refer to section 1.6 and the Foundation Knowledge Guide)

- asking what they need to feel comfortable, increasing the likelihood they continue to engage with your service.

You could also consider the physical safety of the environment, including:

- removing objects that could be used as weapons

- separating waiting areas from consultation areas (if applicable)

- making sure there are different access points and times for people who are known to use violence and victim survivors (if applicable)

- being aware of exits and ways of moving between spaces, including for staff and other service users.

Do not ask a person known or suspected to be using violence questions about their risk behaviours in front of any adult, or child victim survivors in their care.

Use a private environment when asking about sensitive and personal information. This is critical to supporting safety and maintaining rapport.

If a victim survivor is present, your organisation should have policies and procedures for safely separating them to provide a private space for conversation.

You can also create a culturally safe, respectful and accessible physical environment by:

- not using stigmatising signage or language (for example, do not include the word ‘perpetrator’ in any room signage)

- displaying artwork that is hopeful, empowering, recovery focused and culturally diverse

- displaying acknowledgment of the Aboriginal custodians of the land upon which your service is located

- displaying a rainbow flag and flags recognising other identities and communities

- having safe and accessible parking.

The benefits of providing a safe environment for people who may use family violence include:

- reducing their resistance to engaging with services and support, and promoting their capacity to seek help

- increasing their motivation and self-efficacy to make positive changes

- reducing their perception of ‘unjust’ persecution, such as by the ‘system’. This perception is sometimes called a ‘victim stance’.

1.5. Communication

Remember

You must not share any information about a victim survivor with the person suspected or known to be using violence. They must not be able to access any information your service may have about the victim survivor. This can escalate risk for victim survivors.

The person using violence may not be aware that the victim survivor or another family member has used your service, or another service.

This means you must not indicate – or allow the person using violence to infer – that you have information that originated from the victim survivor.

Communicating appropriately with people who use family violence is essential for establishing a safe and respectful environment.

To build trust, you should provide key information about what you and/or your service is there to provide, and set clear expectations.

Many of the skills that you already use in your role will help you establish a safe and respectful environment.

As a priority, make sure the service user can communicate with you, and address any barriers to communication, including using plain English resources. Make adjustments or identify supports for people with disabilities that affect their communication.

1.5.1. Addressing barriers to safe, respectful, and responsive communication

People’s lives and identities are complex. Service users may face multiple barriers to engaging with your service.

These may include the circumstances or reasons why a service user is engaged with your service – such as being mandated to or having voluntarily accessed your service.

You should also understand how discrimination, structural inequality and barriers affect Aboriginal people, people from diverse communities, and people from at-risk age cohorts (refer to section 12in the Foundation Knowledge Guide).

Considering these factors with an intersectional lens supports you to identify and respond to barriers to engagement.

These barriers may arise from a lack of specific responses to the service users diverse needs – including culture, language proficiency, identity, gender, physical and cognitive abilities and other needs.

Barriers may also arise from a lack of training for staff in identifying co-occurring issues, such as poor mental health, alcohol and other drug (AOD) use or homelessness.

The following examples show how to address common barriers to communication:

- Arrange access to an accredited interpreter if needed (level three if possible) or an Auslan interpreter for people who are Deaf or hard of hearing. For some communities with smaller populations, it is more likely an interpreter may know the victim, or the person using or suspected to be using family violence. You can avoid identifying names or use an interstate interpreter. Where possible, offer an interpreter of the same gender as the service user. Children, family members and non-professional interpreters should not be used. It is essential to ensure the service user understands the information available to them, using plain English and other forms of communication where necessary.

- Some service users may be more comfortable with a professional from their own community or cultural group or with a support person present. Ask the person about their choice of service and refer and/or engage by secondary consultation with services that work with the service user’s community. Continue to use reflective practice in your consideration of culture and the impact of dominant white culture on engagement barriers, and how you can adjust your practice to support safe engagement.

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people may feel more comfortable if your service or organisation has Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander staff. You should also consider being less rigid in your intake approach, physical setting and time constraints. Your agency’s reputation and history regarding child removal or negative engagement with Aboriginal people may affect the level of trust you can achieve. Understanding context and using similar language to the service user is essential.[2] Use engagement approaches that incorporate narrative counselling techniques. Consider past and current impacts of colonisation, displacement, historic and ongoing child removal, trauma and racism.[3]

- Make sure the person can access any communication adjustments or aids if they have a disability affecting their communication or other communication barriers and confirm that they understand the information provided to them. If the person has a disability or developmental delay that affects their communication or cognition, seek their advice or the advice of a relevant professional regarding what adjustments might assist. (This includes any augmented or alternative communication support, such as equipment or communication aids.) If the person has an existing augmentation or alternative communication support plan in place, you should engage directly with them, with help from a support worker, advocate or other communication expert, if required, to help you navigate its use.

- If the service user has a cognitive disability or requires communication adjustments, it is important to work on the assumption they have capacity to engage and adapt your service to overcome any communication barriers. Talk to the person directly – rather than through their nominated advocate, support person or carer. Take the time you need to work with the person at their pace. This will help to build trust and rapport and support disclosure of information. If required, you can consult with the Office of the Public Advocate for further advice.

- Gender-sensitive policies and procedures will improve your service’s accessibility. More service users will feel welcome if your organisation’s forms, resources and approach is inclusive of all gender identities.

A commitment to continuous improvement, professional development and reflective practice will strengthen your ability to engage safely with all service users and minimise barriers to communication.

Section 10.3.1 of the Foundation Knowledge Guide has detailed information on applying an intersectional analysis when working with people using family violence.

1.6. Cultural safety and respect (using intersectional analysis in practice)

Reflect on information provided in the Foundation Knowledge Guide and the MARAM Framework on using an intersectional lens.

The Foundation Knowledge Guide and Section 1.12 of this chapter include more information on recognising personal bias and understanding the experience, structural inequality and barriers experienced by Aboriginal people and people from diverse communities or at-risk age groups.

Cultural safety is about creating and maintaining an environment where all people are treated in a culturally safe and respectful manner.

All people have a right to receive a culturally safe and respectful service. This means:

- respecting Aboriginal people’s right to self-determination

- not challenging or denying a person’s identity and experience

- showing respect, listening, learning and carrying out practice in collaboration, with regard for another’s culture whilst being mindful of one’s own potential biases

- undertaking genuine and ongoing professional self-reflection about your own biases and assumptions including with more experienced professionals

- listening and understanding without judgement.

Providing a culturally safe response also involves understanding how family violence is defined in different communities, including for Aboriginal communities. Further information is outlined in the MARAM Framework and section 12 of the Foundation Knowledge Guide. Assessment processes must be respectful and inclusive of broad definitions of family and culture.

For example, it is particularly important not to assume who is ‘family’ or ‘community’, but rather to ask who should be considered in risk assessment and management.

1.7. Asking about identity

Always enquire about and record the language, culture and other aspects of identity of each family member.

Never assume you know these, or that they will be the same for each family member.

It is good practice to openly acknowledge the culture a person identifies with in a positive and welcoming way.

Information about a person’s identity must inform all subsequent assessment and management responses.

Until you have built trust and rapport, some people may choose not to disclose their identity groups. This might be for a range of reasons, including fear of discrimination based on past experience.

For Aboriginal people, structural inequality, discrimination, the effects of colonisation and dispossession, and past and present policies and practices, have resulted in a deep mistrust of people who offer services based on concepts of protection or best interest.

You should be mindful of how this might affect a service user’s actions, perceptions and engagement with the service.

Acknowledge the impact these experiences may have had on the person, their family or community. Assure the person that you will work with and be guided by them. Affirm your commitment to providing an inclusive service and minimising future discriminatory impacts in their engagement with you.

It is also important to recognise the strength and resilience of Aboriginal people and culture in the face of these barriers and structural inequalities.

Kinship systems and connection to spiritual traditions, ancestry and country are all important strengths and protective factors.

The role of family is critical, and Aboriginal children are more likely than non-Aboriginal children to be supported by an extended, close family. Assessment of Aboriginal children must support cultural safety and take into account the risk of loss of culture.

You can find out more about cultural safety, Aboriginal identity and experience in section 12.1.4 of the Foundation Knowledge Guide.

People who have diverse individual and social identities, circumstances or attributes may not choose to disclose these to you unless they trust you and feel a rapport with you.

You can support disclosure by never assuming how the person and their family members identify.

For example:

- Don’t assume gender identity (which can result in misgendering) based on a person’s voice, appearance or how they dress, as this can lead to disengagement.

- You can ask what pronouns a person uses by saying ‘I use [she and her / he and him / they and them] pronouns, what do you use?’. This lets the person know you provide an inclusive and respectful service.

- You can ask if a person identifies as LGBTIQ, and if there is a way you can support them to engage with your service, or if there are external supports available to ensure they are comfortable engaging with you.

- You can ask if the person has any disabilities, developmental delays or mental health issues, and if there are any supports or adjustments you need to make.

Services should be aware that identity is complex, and that aspects of a person’s identity should be considered as part of their whole experience. To help inform your response, you might choose to engage in secondary consultation with specialist family violence services with an expert knowledge of a particular diverse community, and the responses required to address the unique needs and barriers faced by this group (see Responsibilities 5 and 6).

You should offer Aboriginal people, people from culturally, linguistically or faith-diverse communities, or LGBTIQ people specialised supports as needed.

This may comprise bilingual and/or bicultural supports. Support from a trusted family or community member, or a group such as an Aboriginal men’s behaviour change group, may provide a crucial support to engagement and sustainable change.

However, do not assume a person would prefer to access a specialist community service. Aboriginal people and people from diverse communities may want to engage with a mainstream service due to confidentiality.

A warm and safe referral to a community service that you have a direct connection and relationship with will assist the service user to engage with an appropriate service. Responsibility 5 and Responsibility 6(information sharing, secondary consultation and referral) provide more on this.

1.8. Building rapport and trust

Building rapport and trust with service users is the responsibility of all professionals. Building rapport and trust with a person you know or suspect is using family violence supports their continued engagement with your service, which provides opportunities to identify, assess and manage family violence risk.

Reflect on the key concepts for practice when working with people using family violence in section 10 of the Foundation Knowledge Guide.

Some people who use family violence may present to services as defensive, wary and self-justifying.

To minimise this while increasing their engagement, consider ways to bring together a trauma and violence-informed approach, culturally safe and responsive practices and authentic communication styles.

This can indicate to the person using violence that you will listen and be present with them and uphold their dignity throughout your engagement.

Do not mistake a trusting relationship for an objectively uncritical one. A core goal of building rapport and trust is to create an environment where family violence narratives and behaviour are easier to identify.[4]

To assist with balancing engagement and rapport building while avoiding collusion, you can also seek supervision and collaborate with managers and colleagues for guidance on particular situations and your approach.

Consider if it is appropriate to engage with a service that can provide culturally specific expertise to support your approach.

Key methods to building rapport and trust include:

- Ask open-ended questions to start the conversation. This might include questions about the person’s day, feelings about coming to your service, or what they might be hoping to get out of the engagement.

- Explain your role, including being clear that assessment of risk (as applicable) is part of your role.

- State your obligations under legislation – including information sharing authorisation. See limited confidentiality statement in Section 1.2.5.

- Invite collaboration, for example, ‘I was wondering if you could help me understand …’.

- Be conversational in your assessment – listen for risk-relevant information, and avoid a call-and-response dynamic, in which you go through a list of questions and the person provides yes/no or one-word answers. The more natural the conversation, the more genuine the person’s response is likely to be.

- Listen for points of tension or discomfort. What topics does a person avoid or gloss over?

- Do not ask ‘why?’ questions. This type of questioning is often experienced as judgement or rejection, especially if the person using violence is experiencing shame.

- Be curious and match your service user’s language, while avoiding colluding with invitations to minimise or excuse violence.

- Understand the person’s context. Be aware of how they express their identity and situation. Be aware of experiences of structural inequality, oppression and discrimination that create barriers to engagement.

- Be aware of how power is operating in the situation. Consider your own identities, culture, assumptions and biases, and your own place in the service system’s creation of structural privilege and power.

- Be mindful of barriers associated with language, cultural meanings and understanding of Australian legal systems for some people from culturally, linguistically and faith-diverse communities. Addressing these, and considering your own culture and dominant cultural assumptions (if applicable), can be an important starting point for rapport building.

- For Aboriginal people, narrative approaches, including sharing of connections, selective sharing of some of your story and deep listening, may be important in gaining trust.

Note that while creating a safe, respectful and non-judgemental environment is key to risk assessment and management processes, there will be times when you are required to take action without the service user’s knowledge or consent, based on information shared with you from the service user or another professional.

1.9. Practice approaches to safe, non-collusive engagement

Use the following approaches when engaging with people who use family violence:

- Prioritise victim survivor safety. All professionals must be aware of victim survivors’ safety and wellbeing in their communication with people using violence. This includes professionals who do not have a role in asking questions about family violence.

- Keep information provided by the victim survivor confidential from the person using violence. Never disclose that you are aware of information provided to you or another agency by a victim survivor. This applies whether a person is suspected or known to be using violence. If a person using violence thinks the victim survivor has accessed a service, or provided any information, they may escalate their violence in retaliation or use the information to further intimidate and coerce the victim survivor.

- Reflect that addressing the wellbeing, needs and family violence risk behaviours[5] with a person using violence can support them. People using violence have values and goals for their family, relationships and themselves. A collaborative, respectful approach is more likely to support ongoing engagement and keep the person using violence in view, compared with a judgemental or confrontational approach. In communicating with people using violence, you should give the dual messages of acceptance of them as people with potential to change, while rejecting coercive or violent attitudes and behaviours and invitations to collude with them.

- Recognise that people who use family violence may seek you to collude with them. Reflective practice can support you to identify whether a person using violence is engaging with your service to reinforce their position of control over the victim survivor. This includes by presenting as charismatic and caring. If a victim survivor feels your service may not believe them if they disclose violence, this may further isolate or demotivate them from seeking help. Responsibility2 has more guidance on responding to invitations to collude.

- Reflect an open attitude and demeanour. Maintain a curious and open approach when you are learning about a service user’s family life and other aspects of their lives. Each person comes to a service with their own history, experience, needs and circumstances. The more you learn about the person’s life, the more information you will have to support effective risk identification, assessment and management opportunities.

1.9.1. Professional curiosity

Professional curiosity is the capacity of professionals to hold a non-judgemental approach while exploring what is happening in the person’s life.

You can do this by seeking clarification or more information to help build an understanding of the person’s life, relationships and experiences. You can also observe their narratives, behaviours or changing presentation over time.

Patterns of family violence behaviour emerge more easily when you give the person using violence space to tell their story.

This does not mean you should believe the person is telling the absolute truth. You should reflect on the experiences of victim survivors as you contextualise the information shared with you.

Holding the victim survivor experience at the centre, you can use professional curiosity and careful questioning to guide the direction and parameters of the engagement. You can then identify risk and opportunities to manage it.

Professional curiosity helps you to:

- set up a professional and respectful relationship

- set expectations for behaviour and engagement

- demonstrate you are willing to hear and work with the person, regardless of their behaviour

- place boundaries around the behaviour as part of, and not intrinsic to, the person

- create a sense of trust and transparency in your work together.

Being open-minded and non-confrontational with the person will foster a sense of trust and minimise the likelihood of risk to victim survivors to escalate.

1.9.2. Respectful and non-judgemental approaches

Research shows that people who use family violence often feel shame or embarrassment at the idea of seeking help for violent and abusive behaviours.[6]

This can lead to avoiding help-seeking, which is often linked to attitudes about traditional gender roles and behaviours – in particular, expressions of masculinity that do not include showing emotion or concern for other men.[7]

People using violence are more likely to engage if they believe that you as a professional and your service are trustworthy and can offer support in a non-judgemental way.

People who use family violence are unlikely to disclose or discuss their behaviour if they feel judged, disrespected or dismissed.

This means they will be more likely to minimise or deny their use of violence, disengage from the service system, and not seek help now or in the future.

To keep the person in view of services and engaged with supports, your conversations should:

- be respectful and non-judgemental

- include professional curiosity

- be non-reactive to the person when you hear behaviours or narratives that are concerning

- use a strengths-based approach.

Strengths-based and healing approaches can be particularly important for Aboriginal people using violence who may be disconnected from country and culture. Cultural strengthening serves as a critical protective factor against violence.[8]

1.9.3. Strengths-based approach

Using a strengths-based approach when engaging with service users does not mean ignoring the risk you or another professional have identified.

Strengths-based practice takes different forms, depending on your role and responsibilities, including:

- recognising the capacity for change (which may inform your referral options)

- identifying protective factors and sites of support that can be drawn upon for safety planning. For Aboriginal people, this includes discussing healing approaches and connections with community, culture and whole of family[9]

- noticing when the person tells you their presenting needs or circumstances related to their risk behaviours are unmet

- identifying internal and external motivation (when considering referrals, risk management actions, and ways to develop their insight and capacity to engage with change work)

- recognising resilience and other individual and community resources that support risk management and change efforts. When working with Aboriginal people, this means you should also practice in a way that values the collective strengths of Aboriginal knowledge, systems and expertise.[10]

1.10. Common emotions and thought patterns of people using violence entering the service system

People who use family violence experience a range of emotions when entering the service system. These emotional processes may produce defensiveness or ‘resistance’ to engaging with you or your service.

Be aware of these common presentations among people who have used family violence and consider your response in order to support safe engagement.

Table 1 lists common emotions and corresponding thought patterns.

Table 1: Common emotions and thought patterns of people using or suspected to be using violence upon entering services

|

Fear |

What is going to happen to me? What is this all about? |

|

Anger |

I shouldn’t have to be here. These people don’t understand me. |

|

Shame |

I am a bad person and I am unworthy of help. |

|

Resentment |

Just wait until I get back at my family member who reported me. I need to stop them spreading these lies. |

|

Suspicion |

These people are out to get me. Who has [victim survivor] been talking to? |

|

Confusion |

Why is this person so interested in me? What have I done? What do they want from me? |

|

Hopelessness |

Nothing will ever get better, it would be a waste of time to try. [Victim survivor/court/child protection] won’t let me see my children, and there is nothing I can do about it. |

1.10.1. Victim stance

People who use family violence may have feelings that they are the ‘true victim’, which is sometimes referred to as taking a ‘victim stance’.

Many people using violence may not recognise they need to address a problem, and if they do, the problem they recognise is unlikely to be the family violence risk they themselves present.

For example, this narrative is common where a system intervention or relationship breakdown related to their family violence has resulted in them being prevented from returning to the family home or seeing their children.

This victim-stance positioning may be in the form of inviting collusion from professionals as a tactic of systems abuse, such as through making false reports against a victim survivor to police, courts or Child Protection.

This may also occur if the person is in a caring role and is using violence towards the person they are providing care for, such as an older parent or person with a disability requiring care and support (who may or may not also be an intimate partner).

The person in this situation may consider themselves a ‘victim of circumstance’ and feel resentment about their caring role.

They may have no or limited insight into their behaviour, or they may have a limited understanding of a need for change.

1.10.2. Limited self-awareness

People using family violence may acknowledge or have some awareness of the impact of their violent or abusive behaviours. However, they are unlikely to recognise their use of violence as a choice or take responsibility for behaviours used to coerce or control victim survivors.

Instead, they are more likely to view their violent and abusive behaviour as a ‘relationship problem’ or a problem caused by other factors, such as use of alcohol and other drugs.

Similarly, the use of violence may have become normalised over a period of time. They may frame the violence as ‘this is how we interact’. This affects their ability to identify their behaviour as violence, and it may be a barrier for the victim survivor to report the violence.

This is why voluntary, overt disclosures of family violence perpetration are rare, and where they do occur, these disclosures do not reveal the full extent of family violence risk.

Your engagement with a person using or suspected to be using violence is an essential component of developing an understanding of family violence risk in a given situation.

1.11. Key methods for trauma and violence-informed practice

Reflect on information in the Foundation Knowledge Guide about trauma and violence-informed practice.

Use the following approaches when engaging with people using violence:

- Remain curious and interested in the person, listen to what they say and be aware of their non-verbal trauma response cues. Invite them to take their time or breaks when needed.[11] Be alert to signs they are agitated or ‘zoned out’. This may indicate they are experiencing the effects of trauma or may indicate heightened risk to the victim survivor. For their own safety, as well as that of victim survivors, make sure they are emotionally safe when they leave.

- Build trust by listening to them respectfully and learning about their life experiences. This will help you to tailor your response to them. It provides context for their use of violence, not a justification for it.

- Provide opportunities for choice during your engagement. For people using violence, who may not have chosen to engage with you or your service, you can build small choices into your process, such as how often and where to meet, how they would like to be communicated with, and being asked what they think would support them to engage with you.

- Collaboration means doing things with a service user instead of for them. Support them to express what they want for their life and set expectations about what your service can do to support them to be safe and respectful in their relationships and stop their use of family violence (or address their presenting needs linked to family violence). Explore the person’s life goals and the sort of person/partner/parent they want to be. This may create or renew a positive narrative and hope and increase their motivation to change.

- Empowerment is critical in correcting the power imbalances created by interpersonal trauma. People using violence use power and control over family members, but they too may have a sense of disempowerment from past trauma experiences. Building on a person’s self-efficacy to change, rather than focusing only on ‘problems’, is essential.[12] Empowerment should focus on pro-social/antiviolence strengths. This can be particularly important for Aboriginal or other cultural groups who have experienced historic or recent disempowerment by society (for example, colonisation, experience of systemic discrimination, child removal).

1.12. Reflective practice and recognising bias when working with people using family violence

When engaging with people using family violence, you should maintain a critical awareness of:

- your role and responsibilities within the system

- the depth of engagement and intervention within your role or service

- how your reflective practice and awareness of biases in your engagement may contribute to stronger risk management, or conversely, where it is absent, may inadvertently contribute to risk

- how your own biases might be used by people using violence in their invitations to collude.

Reflecting on professional biases and agency-level responses can help professionals and services address issues of discrimination and marginalisation and increase opportunities for service engagement.

In particular, you can identify barriers to access for a person using or suspected to be using violence by considering:

- how you can allow people who use violence to access resources and professional support

- how service exclusion, such as withdrawing services, can increase risk to victim survivors by reducing the visibility of the person using or suspected to be using violence within the system

- how communication styles, such as confrontation and direct challenging of a person using or suspected to be using violence, can reinforce already held strong feelings about system injustices and increase service disengagement.

Biases can lead to increased risk for victim survivors as well as people using family violence. Unconscious and conscious biases about a person’s use of violence, identity or circumstances may limit capacity of professionals to observe narratives or behaviours that can indicate use of violence.

You should engage in reflective practice by considering how these might affect your decisions, capacity and willingness to engage with people using family violence, and approaches to applying Structured Professional Judgement.

When seeking to identify conscious and unconscious bias, you can consider:

Table 2: Examples of conscious and unconscious bias

|

Examples of unconscious bias |

Examples of conscious bias |

|

|

1.13. Responding when you suspect a person is using family violence

Throughout your service provision, it is likely you will come into contact with service users you know or suspect are using family violence.

This may be indicated by the person’s narrative or behaviours, such as overt or subtle disclosures, or information shared by another service or organisation.

A person using violence may use collusive tactics to try to align you with their position, in order to justify, minimise or excuse their use of violence or coercive behaviour, or to present themselves as a victim survivor.

This is known as collusion. These behaviours are outlined in section 10.5 of the Foundation Knowledge Guide and in perpetrator-focused Responsibility 3.

Identifying who is perpetrating family violence can be complex.

In order to respond safely when you suspect a person is using family violence, you should understand:

- narratives that indicate family violence

- when it is safe to ask questions or when to simply observe

- why a person using or suspected to be using violence may not be aware their behaviour is abusive or violent.

Guidance on understanding misidentification of victim survivors and people using or suspected to be using violence, and identifying predominant aggressors is outlined in section 12.2.1 of the Foundation Knowledge Guide as well as in Responsibilities 2, 3 and 7.

If you suspect a person is using family violence, you should not engage with them directly about family violence, unless you are trained or required to do so to deliver your service.

This is because confrontation and intervention may increase risk for the victim survivor.

Instead, you should consider proactively sharing information, as authorised, with a specialist family violence service that can support the person you suspect is experiencing family violence (see Responsibilities 5 and 6).

You can also talk with other professionals in your service who have a role in working with people who use violence, or contact a specialist family violence service with expertise in assessing risk, and who can safely communicate with a person who may be using violence to engage them with appropriate interventions and services, such as behaviour change programs, explored further in Responsibilities 3 and 4 and/or7 and 8.

1.14. Next steps

Responsibility 2 provides guidance on identifying narratives and behaviours linked to evidence-based family violence risk factors.

All professionals who suspect that a person is using family violence should use the guidance in Responsibility 2.

Responsibilities 3 and 4 provides guidance on asking questions about presenting needs and circumstances related to family violence risk factors (risk-relevant information) and exploring motivation to manage risk is in.

Footnotes

[1] Services that are not prescribed under FVISS or CIS should consider how to seek consent from service users to share information under privacy laws.

[2] Using the language of the client is an essential part of meeting them where they are at. This practice must be used alongside a balanced approach to engagement, that supports professionals to recognise and address invitations to collude.

[3] Day A et al. 2018, ‘Assessing violence risk with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander offenders: considerations for forensic practice.’ Psychiatry, Psychology, and Law 25(3), 452–464.

[4] Kozar C 2010, ‘Treatment readiness and the therapeutic alliance’, Transitions to better lives: offender readiness and rehabilitation, pp. 195–213.

[5] Specialist family violence services work with known perpetrators about their use of violence. Other services play an important role in keeping a perpetrator in view, which supports ongoing risk assessment and management. Specific services address specific risk factors, such as drug and alcohol services.

[6] Hashimoto N, Radcliffe P, Gilchrist G 2018, ‘Help-seeking behaviors for intimate partner violence perpetration by men receiving substance use treatment: a mixed-methods secondary analysis’, Journal of Interpersonal Violence. doi: 088626051877064.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Department of Health and Human Services 2018, Dhelk Dja: Safe Our Way – Strong Culture, Strong Peoples, Strong Families, State Government of Victoria, Melbourne.

[9] Where safe to do so, ensure the victim survivor also has case management and wrap around support.

[10] Department of Health and Human Services 2018, Dhelk Dja: Safe Our Way – Strong Culture, Strong Peoples, Strong Families, State Government of Victoria, Melbourne.

[11] Kezelman and Stavropoulos 2018, Talking about trauma: guide to conversations and screening for health and other service providers, Blue Knot Foundation, p. 60.

[12] Wendt et al. 2019, Engaging with men who use violence: invitational narrative approaches, ANROWS Research Report, Issue 5, p. 27.

Updated