Download and print the PDF or find the accessible version below:

Appendix 3 - Adult Person Using Violence Intermediate Assessment Tool 3

Appendix 4: Intermediate assessment conversation model

Appendix 5: Screening questions for cognitive disability and acquired brain injury

Appendix 6: Recognising suicide risk in the context of adult people using violence

Note

This Practice Guide is for all professionals who have received training to provide a service response to a person they know is using family violence.

The learning objective for Responsibility 3 builds on the material in the Foundation Knowledge Guide and in preceding Responsibilities 1 and 2.

3.1 Overview

Professionals should refer to the Foundation Knowledge Guide and perpetrator-focused Responsibilities 1 and 2 before commencing intermediate risk assessment.

This chapter guides you in undertaking an intermediate risk assessment. This helps determine the level or ‘seriousness’ of risk presented by a person using family violence towards an adult or child victim survivor.

You can do this assessment directly after a service user discloses using family violence. You can also do it when you become aware of information confirming the person is using family violence, such as from another service, the victim survivor/s or a third party.

Intermediate risk assessment is also used to assess and monitor risk over time.

Key capabilities

This guide supports professionals to have knowledge of Responsibility 3, which includes:

- asking questions to obtain information related to risk factors

- using the model of Structured Professional Judgement in practice

- using intersectional analysis and inclusive practice

- using the Adult Person Using Violence Intermediate Assessment Tool

- understanding how observed narratives and behaviours and presenting needs or circumstances link to evidence-based risk factors

- forming a professional judgement to determine the level or seriousness of risk, including ‘at risk’, ‘elevated risk’ or ‘serious risk’/‘serious risk and requires immediate protection/intervention’.

When working with a person using violence, an intermediate risk assessment focuses on information gathering and an analysis of:

- responses to prompting questions asked directly to the person using violence (refer to the Intermediate assessment conversation model in Appendix 4)

- your observation of the person’s narratives and behaviours (refer to Responsibility 2)

- information shared by other services about risk factors

- the person’s disclosed motivations for seeking help or support for their presenting needs or family violence behaviours

- family violence behaviours to identify recency, frequency and patterns, including patterns of coercive control.

The Adult Person Using Violence Intermediate Assessment Tool (Intermediate Assessment Tool) in Appendix 3 provides a structure to support your analysis of information and application of Structured Professional Judgement to determine the level of risk.

Remember, Responsibility 3 of the victim survivor–focused MARAM Practice Guides provides practice considerations, guidance and tools for assessing risk for children, young people and adult victim survivors.

Responsibility 3 of the perpetrator-focused MARAM Practice Guides (this document) helps you identify and assess the person’s use of violence and its impact on children, their parenting role and co-parenting relationships.

It also considers the person’s motivations and capacity for change in relation to their parenting role, prioritising the safety, wellbeing and needs of children and young people.

Each guide prompts you to consider what is safe, appropriate and reasonable, considering the age and developmental stage of the child or young person as the first guiding consideration.

After an intermediate risk assessment, a professional may escalate the risk assessment (through secondary consultation or referral) for a comprehensive assessment to be undertaken by a specialist perpetrator intervention service practitioner.

Remember

Adolescents who use violence need a different response than adults who use violence.

You should consider their age, developmental stage, whether they are also a victim survivor of violence, and their therapeutic needs.

You should also consider the specific protective factors that will support their development and stabilisation and recovery (such as family reunification where it is safe to do so), as well as overall circumstances.

For adolescents who are nearing adulthood, particularly if they are using intimate partner violence, you may use this guide with caution.

You should consider their age and developmental stage when asking prompting questions to explore risk, behaviour and motivation.

Narratives and behaviours indicating family violence from adolescents and young people nearing adulthood can be recorded in the Intermediate Assessment Tool.

Refer to MARAM Practice Guides for working with adolescents using violence for more information.

3.1.1 Who should undertake intermediate risk assessment and in what situations?

This guide is for professionals whose role is linked to, but not directly focused on, family violence.

As part of, or connected to, your core work, you will engage with people who are:

- using family violence (identified by observation of their narratives or behaviours, through direct disclosure, or information shared from another service/third party)

- using family violence (not yet identified or disclosed) where the presenting need may contribute to their use of violence and controlling behaviours, for example:

- their presenting need is related to mental health or drug and/or alcohol use, and may relate to family violence risk factor/s

- their presenting need is masking or hiding their use of violence (for example, they are using the presenting need to justify, minimise or deny the use of violence)

- mandated to attend your service (their use of violence has been identified by the referring service/agency or disclosed)

- in a crisis situation as a result of their presenting needs or circumstances or use of family violence (and they are or are not aware/ready to admit/disclose this).

3.2 Structured Professional Judgement in Intermediate risk assessment

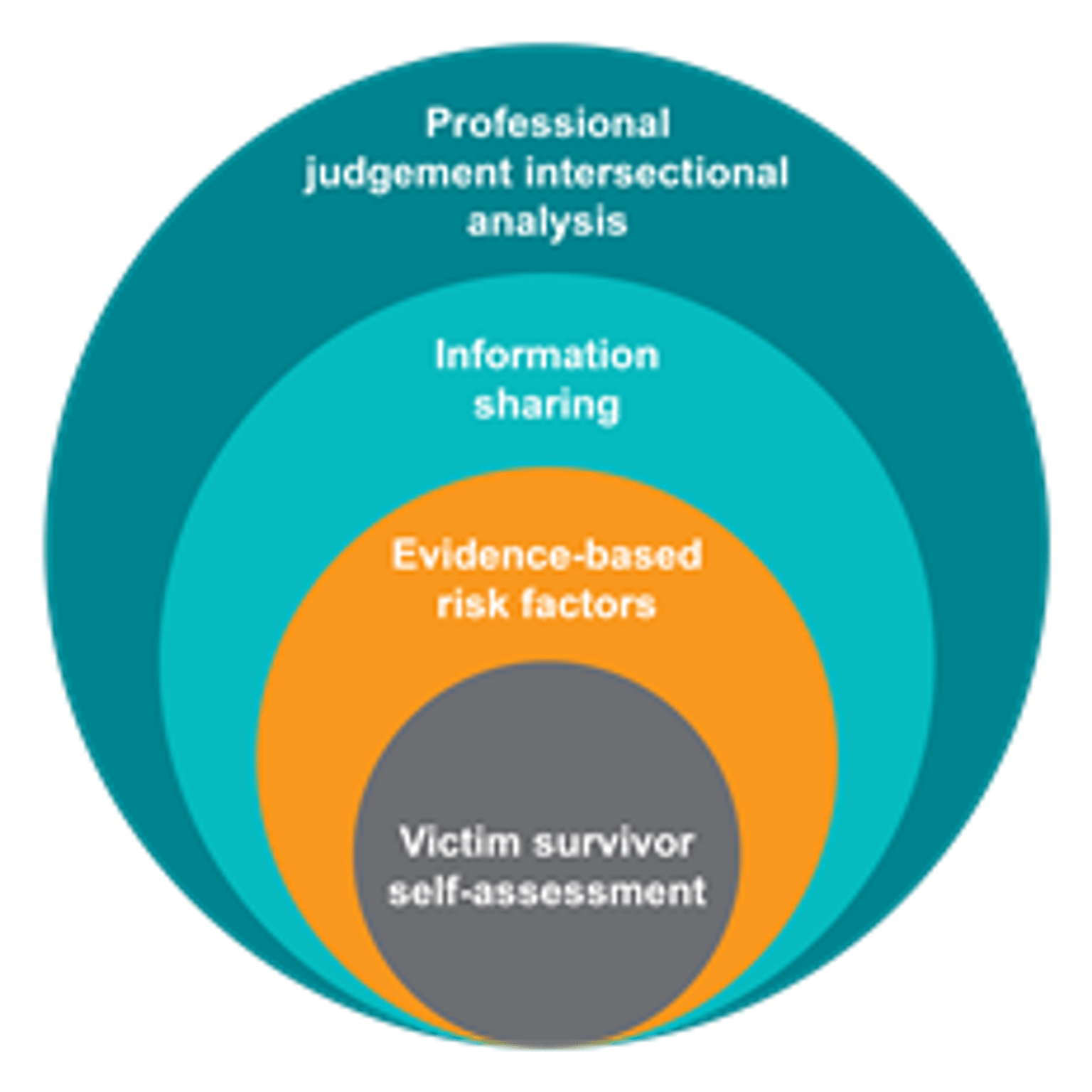

Reflect on the model of Structured Professional Judgement when working with a person using violence, as outlined in Section 10.1 of the Foundation Knowledge Guide.

The model of Structured Professional Judgement is an approach to risk assessment that supports you to determine the level or seriousness of risk presented by a person using family violence.

It provides a framework for analysing information to identify and understand patterns of family violence.

Risk assessment with a person using violence relies on you or another professional:

- centring the lived experience and risk to the victim survivor during your assessment

- identifying the evidence-based risk factors present.

Victim-centred practice ensures that the lived experience, dignity and safety of all victim survivors is at the centre of your assessment.[1]

You should apply your knowledge of the impact of family violence on adult and child victim survivors to understand or contextualise their experience of the person using violence.[2]

You can share information and seek the advice and views of victim survivor advocates and/or specialist family violence services or other professionals working with adult and child victim survivors to understand their self-assessed level of risk and identify protective factors.

You can identify and analyse evidence-based risk factors through:

- your observations of the person using violence’s presentation, violence-supporting narratives and behaviours, including attitudes and accepted norms that may underpin a person’s choice or intention to use violence

- direct disclosures about their use of family violence behaviours

- the person’s presenting needs and circumstances related to family violence risk factors

- your observations of patterns of coercive control, including where behaviours are targeted towards a victim survivor’s identity, lived experience, needs or circumstances

- your observations or direct disclosures of motivations for engaging with your service or a family violence service.

You can seek and share information to inform this approach from a variety of sources, including:

- observing or ‘assessing’ the person using violence directly

- proactively requesting or sharing information, as authorised, about the risk factors present, observations of narratives or behaviours of the person using violence, or other relevant information about a victim survivor’s or perpetrator’s needs or circumstances. This may be shared by other professionals or services, the victim survivor (if disclosed directly to your service), or a third party.

Intersectional analysis[3] must be applied as part of Structured Professional Judgement.

This means understanding that a person may experience structural inequalities, barriers and discrimination throughout their life.

These experiences will provide context for:

- their own identity and lived experience

- their understanding and capability to name, disclose or understand what constitutes violent behaviours

- how they manage their risk behaviours and safety towards victim survivors and themselves

- their engagement or access to services responding to their use of family violence, presenting needs and circumstances.

Applying a person-centred, trauma and violence-informed lens as part of Structured Professional Judgement also supports a better understanding of the person using violence (outlined in Section 10.1 in the Foundation Knowledge Guide).

Together, the elements underpinning Structured Professional Judgement provide a structure for gathering and analysing information to assist you to determine the level or ‘seriousness’ of risk. You will use this analysis to determine intermediate level risk management responses, as required (refer to Responsibility 4).

Refer to the Foundation Knowledge Guide and Responsibility 1 for information on trauma and violence-informed practice.

Some people who use family violence have experienced trauma in their lives. They may need support to address this, while also addressing their use of family violence.

If your role is not to address trauma, you should support the person using violence to access a referral to a specialist service.

You may also seek secondary consultation to ensure no further trauma or harm occurs in your engagement approach.

When working with Aboriginal people using violence, it is particularly important that you understand trauma, including intergenerational trauma, and the person’s healing journey as part of your engagement.

In some circumstances, experiences of trauma are a barrier to engagement in conversations about family violence risk or may be used to seek your collusion with a victim stance (refer to Section 3.6).

Trauma and violence-informed practice supports you to engage with the person using violence. You can acknowledge the trauma they may have experienced, minimise further trauma and reduce the likelihood of escalating the level of risk.

Engaging with a person using family violence is critical to them stopping the violence, reducing risk and supporting motivation for behaviour change.

Refer to Responsibilities 1 and 2 for guidance on engaging in a respectful, safe and non-collusive way to support a person using violence’s ongoing contact with the service system. This also increases opportunities to monitor and manage the risk they present, while actively working towards behaviour change.

Responsibility 3 requires a clear understanding of the drivers of family violence (outlined in the Foundation Knowledge Guide) and the circumstances and factors that contribute to the person’s choice to use family violence (refer to Responsibility 2).

3.2.1 Information sharing to inform your assessment

Information sharing is a crucial part of your intermediate risk assessment practice.

Responsibility 6 provides further guidance on ‘risk-relevant’ information when sharing information about a person using violence.

The Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme Guidelines and Child Information Sharing Scheme Guidelines outline how to make requests and share information if you are authorised under these schemes.

Limitations on privacy and confidentiality should be clearly explained at initial engagement unless it would increase risk to a victim survivor (refer to Responsibility 1 and Responsibility 6).

You should document in the Intermediate Assessment Tool whether a limited confidentiality conversation would increase risk to the victim survivor from the person using violence.

Intermediate risk assessment of a person using family violence is a collaborative activity. You undertake it with other professionals and services working with the person using violence, as well as adult and child victim survivor/s[4] and other family members (where relevant).

You may request information before engaging with the person using violence, particularly if:

- referral processes alert you to high-risk factors that may require an immediate risk management response to reduce or remove an identified threat

- you require further information about the risk the person presents to manage their attendance at your service, including where the identified victim survivor also attends your service.

If you identify information that risk is escalating or imminent, and you are not working with the victim survivor, you should:

- call police on Triple 000

- seek secondary consultation and share information with specialist family violence services to support risk management responses.

3.3 Intersectional analysis and inclusive practice in intermediate risk assessment

Reflect on guidance about applying intersectional analysis in the Foundation Knowledge Guide.

The experience of the person using violence is shaped by multiple identities, life experiences and circumstances.

Applying intersectional analysis means considering the person in their context. This involves recognising how experiences of structural inequality, barriers and discrimination can affect the person’s trust in services and understanding of their use of violence.

It builds a greater understanding of the person you are engaging with. This allows you to assess risk, establish risk management strategies and support behaviour change.

It also supports you to reflect on your own views, biases and beliefs about a person's use of family violence and to respond safely and appropriately in practice.[5]

Experiences such as service barriers and discrimination related to a person’s identity can influence how they might:

- talk about their use of violence, or recognise that their behaviour, beliefs and attitudes are linked to or reinforce their use of violence

- identify the service options available to them, based on actual or perceived barriers. This may be due to discrimination or inadequate service system responses experienced by themselves or people they know, including institutional or statutory services

- perceive or talk about the impact of their behaviours on their family and adult and child victim survivor/s. You may observe this through narratives that minimise, justify or blame others for their behaviour.

Use professional curiosity to remain open to the way the person using violence presents and engages with you. You can respond to their experience of systemic barriers without colluding with a narrative that justifies violent or abusive behaviour.

This includes:

- identifying and recording any concerns the person using violence has about engaging with your service. By considering their identity, circumstances or previous experiences with the service system, you can ensure your responses are safe and respectful

- engaging in a culturally safe and appropriate manner, including offering warm referral to a community specific service if the person using violence chooses. Engage with other agencies and/or the services of a bicultural/bilingual worker (ideally who is trained in family violence). This may be particularly important to assist with working with people from multicultural communities so that narratives of justification, denial and minimisation can be explored appropriately

- discussing supports available if Aboriginal people who use violence choose to engage with non-Aboriginal services due to privacy and confidentiality concerns. This may include exploring the possibilities of collaborative work between mainstream and Aboriginal community organisations or providing an Aboriginal support person

- seeking secondary consultation and possible co-case management with a service that specialises in responding to people from diverse communities in the context of family violence (refer to Responsibilities 5, 6 and 9)

- where safe and appropriate, discussing concerns you have about the risk they present to themselves and others because of the perceived or real barriers they face in seeking help.[6]

It is important that you explore and understand the person’s:

- individual needs and circumstances, and how these relate to their use or pattern of family violence, as well as other life choices they may have made

- underlying concerns or any reluctance they have about recommended services or engagement with the system (for example, resistance to support and change)

- relationships with any victim survivor/s (including each child and/or family members) residing in the household to ascertain other risks of family violence for each person.

Remember

Refer to Responsibility 2 for guidance on the conditions that support the development and use of family violence.

A person’s identity, early life experiences and circumstances are not excuses for their use of family violence, but they may contribute to their use of violence.

Remember to reflect on and challenge your own biases.

Violence and violence-supporting beliefs and attitudes are not an inherent part of any culture and should not be used to justify a person’s use of violence.

These biases and assumptions can increase the risk of collusion with a person using violence and minimise the experience and risk to victim survivors.

Use intersectional analysis, to identify and understand a person’s history of experience of violence and experiences of structural inequality or barriers to their willingness to engage or trust your service.

Secondary consultations with professionals and services can assist you to provide appropriate, accessible, inclusive and culturally responsive services to the person using violence.

3.3.1 Assessing risk when cognitive disability is present, including acquired brain injury

Section 12.1.17 in the Foundation Knowledge Guide provides information on the prevalence, presentations and responses required in relation to people who use violence who have cognitive disability, including acquired brain injury (ABI).

Appendix 5 provides guidance on screening for cognitive disability including ABI indicators with people using violence.

The Intermediate Assessment Tool for people using violence includes an intake field to record if the person using violence and/or victim survivor has cognitive disability.

You can also record the existing or required professional or therapeutic service supports in Section 2 of the Intermediate Assessment Tool, ‘Presenting needs and circumstances’. You can use Sections 1 and 2 to record comments on how cognitive disability is relevant to the person’s narratives and behaviours or supports required to respond to presenting needs.

Practice considerations for people with cognitive disability

You should have some understanding of cognitive disability, including:

- how this may affect presentation and capacity of the person using violence to communicate with you and the adjustments needed to ensure your communication approach enables engagement (Responsibility 1)

- observable indicators that they may have a cognitive disability

- how to screen for cognitive disability indicators, to inform your understanding of their narratives and behaviours and guide decision making on levels of risk

- when secondary consultation and referral is needed:

- for support on communicative and neuropsychological assessment of their cognitive disability (refer to Responsibilities 5 and 6). This can inform service adjustments required to enable appropriate, effective interventions and address engagement barriers

- to respond to significantly reduced cognitive capacity. This may be for the purpose of upskilling professionals, such as in making changes to the environment and minimising the risk of aggression. In some instances, management of these cases may also be occurring within Transport Accident Commission (TAC) or National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) frameworks

- for comprehensive risk assessment and management for the person with cognitive disability using violence. This includes support to tailor approaches and interventions to address the use of violence and safety for victim survivors (Responsibility 7 and Responsibility 8).

3.4 How to use the Intermediate Assessment Tool

A stand-alone template for the Adult Person Using Violence Intermediate Assessment Tool is in Appendix 3.

The purpose of the Intermediate Assessment Tool is to:

- identify the narratives and behaviours you observe that may indicate family violence risk

- identify family violence risk factors and behaviours by sharing information with other sources, as well as asking prompting questions when engaging with the person using violence

- identify presenting needs and circumstances that may be related to risk, increase the level of risk, impact on the person’s capacity to act safely or take responsibility, or serve as protective factors

- consider the information gained through the assessment process and apply Structured Professional Judgement to identify patterns of coercive controlling behaviour, the person’s intent or choice to use violence, and any motivations to engage and change behaviour. This analysis will support you to determine the level of risk at a point in time or changes in risk over time.

The Intermediate Assessment Tool asks you to note how you have formed the belief they are using violence.

This may be from:

- direct disclosure (from the service user)

- victim survivor disclosure

- observation of family violence risk factors (narratives or behaviours)

- information shared by another service or professional or third party (Victoria Police Family Violence Report (FVR, also known as an L17), Child Protection report, other risk assessments or information about use of violence shared by another service)

- referred or court mandated engagement.

Consider this information in your analysis of the person’s intent or choice to use violence and motivation to engage and change behaviour.

The Intermediate Assessment Tool includes intake information and sections that help you to collect and analyse risk-relevant information.

This includes:

- Section 1: Observed narratives and behaviours indicating or disclosing family violence risk factors. Refer to Responsibility 2 for guidance on identifying beliefs, attitudes and behaviours linked to the use of family violence and any narratives indicating minimisation or justification. These narratives may support you to identify underlying aspects of the person’s intent or choice to use violence.

- Section 2: Presenting needs and circumstances that may contribute to risk behaviours, or function as a protective factor. Use the person in their context approach to understand and record any presenting needs and circumstances outlined under the areas of identity/relationships, community/social connections, systems interventions and practical/environmental supports.

- Section 3: Presence of risk factors identified by information sharing, observation or disclosure (person using violence, victim survivor, third party). Record the presence and detail of evidence-based risk factors, noting the source of information, including from other professionals and services working with the person using violence, or adult or child victim survivor. Information may be shared through professional collaboration and coordination processes. Record details of any risk factors requiring immediate response and seek secondary consultation to escalate the situation to Victoria Police and/or specialist family violence services.

- Section 4: Patterns of family violence behaviour and motivations. Patterns may be identified from understanding the types of behaviours used over time, including recency and frequency, and any links to situational circumstances or events. Patterns of behaviour may be different for each adult or child victim survivor. Motivation for the person’s engagement about presenting needs may indicate likely motivations and readiness to engage for the purpose of addressing family violence behaviour.

- Section 5: Determining level of risk to an adult or child victim survivor, self (person using violence) or community/professionals. Record if the tool was used to support a determination of the predominant aggressor (where misidentification is suspected), identified patterns of coercive control and rationale for the level of risk.

An intermediate risk assessment may be completed over a number of service engagements as you build rapport and a professional relationship with the person using violence.

3.5 Understanding the intermediate risk assessment process and risk levels

Assessing risk occurs from the point of first contact and throughout your ongoing engagement with the person using violence.

Ongoing risk assessment helps build your understanding of the person in their context. This includes their risk behaviours, narratives, presenting needs and circumstances, and the impact of this on victim survivors over time.

Intermediate risk assessment can be built into your existing organisational intake and assessment processes.

You may already collect information relevant to the evidence-based risk factors or use direct questioning, as appropriate, to explore the person’s life situation and behaviours.

3.5.1 Using your existing intake and engagement processes to inform risk assessment

Refer to Responsibility 1 for guidance on safe engagement to establish trust and rapport supporting your existing organisational intake and assessment processes.

Your conversation with the person using violence should outline a process that incorporates:

- taking notes and filling out the service’s intake and other relevant assessment forms[7]

- talking about the wellbeing and safety of all family members, including the person using violence (this is not just family violence–specific but for addressing a range of presenting needs and circumstances)

- information sharing (including advising the person using violence of their limited confidentiality)

- discussing the need to ask some challenging or difficult questions, if required, to better understand the person’s needs and circumstances

- discussing what a safe environment looks like for the person using violence to discuss their needs

- discussing what a safe environment looks like for you as a worker.

Few people who use, or are suspected of using family violence, decline the process outlined above.

However, they may not disclose honestly or fully, and they are likely to provide a narrative that reflects their minimising, justifying or victim stance (discussed in Section 3.6).

If they refuse to participate, record this as a possible risk indicator. It highlights a level of resistance to address issues, including their use of family violence.

It may also indicate risk of disengagement.

You can seek support to navigate resistance or refusal through secondary consultation and supervision.

Your risk assessment process will be informed by:[8]

|

Outcome |

Action |

|

Building trust through safe, non-colluding practices |

Ask questions and listen to answers in a balanced, non-judgemental way. You can listen and respectfully not agree with the responses. Use active listening skills and practice professional curiosity to:

|

|

Identifying the motivation to engage[9] |

Understanding the capacity of the person using violence and/or driver of motivation to engage with your service is informed by whether they:

|

|

Gathering risk-relevant information |

Intake Consider risk-relevant information recorded in your organisation’s client intake form to build further understanding of the presenting needs or circumstances of the person using violence. For example, presenting needs such as housing and homelessness issues and gambling. Intake forms also often contain information about family violence evidence-based risk factors, including alcohol and drug use, employment, education, and financial stability. Presenting needs and circumstances Identify risk factors and risk-relevant information from the presenting needs, and other needs and circumstances gained throughout the session/over time. |

|

Analysing risk-relevant information |

Analyse information gathered with a risk lens, building an understanding of the ‘person in their context’ and family violence risk presented by the person using violence, as well as their capacity and motivations to take (a level of) responsibility for their use of violence. Assess the level of risk through evidence-based risk factors, observations of their narratives and behaviours, disclosures (if any), information sharing from other professionals or services, and/or the victim survivor/s. Analysing risk-relevant information also requires you to identify patterns of coercive controlling behaviour over time. |

|

Ongoing engagement and keeping the person using violence in view |

This engagement may be the first time the person using violence has a conversation about their presenting needs and circumstances, family relationships, motivations and/or use of family violence. It is important you meet the person using violence ‘where they are at’. Do not rush an assessment ‘to get it completed’, as this:

Using a strengths-based approach, including acknowledging help-seeking behaviour and feelings of shame or discomfort, may communicate to the person using violence you are there to support them. Strength-based approaches when engaging with a person using violence will direct conversations towards implementing strategies to address their presenting need and the level of family violence risk present, in a collaborative and empowering way for the person using violence. These approaches support the person to identify how they can address their needs, giving them responsibility and ownership for their decisions, actions and behaviours. This builds the foundation for accepting responsibility for their use of violence and the impacts on victim survivors. Offering ongoing engagement, where appropriate to your service, is a way to support the person using violence to remain ‘in view’ of the service system. Supporting the person to address their needs and stabilise their life circumstances is a useful risk management strategy. |

|

Responding to change in risk over time |

Ongoing risk assessment supports you to monitor for changes in behaviour, needs and circumstances over time. Changes to presentations and patterns of risk will require you to update your risk management actions and interventions. This includes responses to presenting needs, information sharing, secondary consultation or referral for specialist perpetrator interventions – or police interventions where there is serious risk requiring immediate intervention. |

3.5.2 Conversation prompts to support intermediate risk assessment

The Intermediate Assessment Tool should be used in conjunction with the Intermediate assessment conversation model (the Assessment conversation model) in Appendix 4.

This provides an example interview structure, including prompting questions to support your engagement with the person using violence.

The Assessment conversation model sets out how to use prompting questions to:

- engage in a dialogue with the person using violence, to uncover their understanding and narrative about themselves and their presenting needs

- build your understanding of how the person using violence views themselves in their context. For example, how they describe themselves as an individual, their relationships and family, and their environment (including social context and community)

- link presenting needs to the impact on relationships and identity, open a conversation about family violence behaviours[11] and encourage disclosure of family violence perpetration (if present)

- support a conversation to uncover information about their underlying beliefs, attitudes and accepted norms that contribute to their intention or choice to use family violence behaviours (refer to Responsibility 2). It may also support early conversations about readiness and motivation to address presenting needs and/or use of family violence, and connect to specialist perpetrator intervention services (further explored inResponsibility4).

You can use the Assessment conversation model with the person using violence in one session or across a series of sessions.

You should apply Structured Professional Judgement to analyse information the person shares with you.

Every engagement, non-engagement, conversation or observation you have with or in relation to the person using violence will inform your decision making in risk assessment and risk management.

The Assessment conversation model provides prompts to help you build rapport with, and elicit responses from, the person using violence. The goal of this is to explore their behaviours, needs and circumstances, including those that may be related to the use of family violence.

It may not be safe or appropriate in the circumstances or at this stage to use the words ‘family violence’ when talking to a person using violence. You may instead describe the behaviour and the impact of the behaviour.

This is not minimising the use of family violence. Rather, this practice reflects a balanced approach to avoid confrontation.

Introducing behaviours and their impact is a step towards enhancing self-awareness. This aims to increase the person’s readiness and motivation to name, identify and address their use of family violence and seek help or referral for specialist interventions and support.

The Assessment conversation model is only a guide. You should use your engagement skills and experience to determine the best approach to your conversation with the person using violence, and navigate the conversation based on their responses and any immediate needs.

When preparing for conversations that can identify risk-relevant information, it is important that you consider the questions in the context of:

- your professional role and goals for engagement

- the person’s presenting needs leading to engagement with your service, and other needs (identified or not)

- the person’s identity, relationships and circumstances

- the nature of the person’s relationship to the victim survivor/s

- the person’s capacity and capability to participate in the conversation.

Planning for a session will be guided by the initial information you have about the person from previous contact, referral forms and information sharing.

You can seek secondary consultation from senior co-workers, your supervisor or team leader.

The prompts in the Assessment conversation model align with the areas of information collected in the Intermediate Assessment Tool at Appendix 3, and are signposted throughout.

Note

People who use family violence will characteristically take little or no responsibility for their use of family violence.

Where they do acknowledge their behaviours, they generally seek to minimise or justify it.

They may not be aware, or do not believe, behaviour such as verbal, emotional, financial and psychological abuse constitutes family violence.

They might frame their use of intimidation, isolation or other controlling behaviours as part of their role in the family, explaining and justifying their behaviour, rather than denying it.

3.5.3 Risk levels

The Intermediate Assessment Tool supports you to record and analyse information to assess the level or ‘seriousness’ of the risk presented by the person using violence to an adult or child victim survivor, to themselves and the community/professionals.

Before you undertake intermediate risk assessment, it is important to understand the levels of risk that the person using family violence may present to victim survivors, as outlined in the table below. The likely circumstances for risk level, below, are examples only. As each person’s situation is different, professionals must apply Structured Professional Judgement to determine the level of risk.

Table 1: Levels of family violence risk when working with the person using violence or victim survivor

|

Risk level |

Person using violence |

Adult or child victim survivor |

|

At risk |

High-risk factors are not identified as present. Some other recognised family violence risk factors are present. |

|

|

Likely circumstances for risk level Police involvement may have occurred.[12] The person using violence may be in a contemplative stage[13] – they are considering the need to address their use of family violence. A Safety Plan is developed for the person using violence, and strategies are supported by them. A Risk Management Plan may have been developed and this is consistent with the risk management strategies developed with the victim survivor/s. Referral to a specialist perpetrator intervention service has occurred or is being considered. The person using violence may:

|

Protective factors and risk management strategies, such as advocacy, information and victim survivor support and referral, are in place to lessen or remove (manage) the risk from the person using violence. Adult victim survivor’s self-assessed level of fear and risk is low, and safety is high. Victim survivor/s are engaged with a specialist family violence service or other appropriate services supporting their safety, needs and recovery. |

|

|

Elevated risk |

A number of risk factors are present, including some high-risk factors. Risk is likely to continue if risk management is not initiated/increased. |

|

|

Likely circumstances for risk level A Safety Plan may not yet be in place for the person using violence, or they are unable[15] to enact it. Risk management strategies may:

Police have been involved on more than one occasion.[17] The person using violence may:

|

The likelihood of serious injury or death is not high. However, the impact of risk from the person using violence is affecting the victim survivor/s’ day-to-day functioning. Adult victim survivor’s self-assessed level of fear and risk is elevated, and safety is medium. Victim survivor/s are engaged with a specialist family violence service or other appropriate services supporting their safety, needs and recovery. |

|

|

Serious risk |

A number of high-risk factors are present. Frequency or severity of risk factors may have changed or escalated. Serious outcomes may have occurred from current violence and it is indicated further serious outcomes from the use of violence are likely, and there may be imminent threat to the life of the victim survivor, themselves or the community. Immediate risk management is required to lessen the level of risk or prevent a serious outcome from the identified threat presented by the person using violence. Statutory and non-statutory service responses are required and coordinated and collaborative risk management and action planning may be required. |

|

|

Likely circumstances for risk level The person using violence:

|

Adult victim survivor’s self-assessed level of fear and risk is high to extremely high and safety is low. Victim survivor/s are seeking an immediate intervention or unable to seek intervention due to levels of fear and risk. |

|

|

Most serious risk cases can be managed by standard responses including by providing crisis or emergency responses by statutory and non-statutory (e.g. specialist family violence) services. There are some cases where serious risk cases cannot be managed by standard, coordinated and collaborative responses and require formally convened crisis responses (such as RAMP). Serious risk and requires immediate protection (for victim survivor) or intervention (for person using violence): In addition to serious risk, as outlined above: Previous strategies for risk management have been unsuccessful. Escalation of severity of violence has occurred/is likely to occur. The person using violence does not respond to internal or external motivators. Concerns and observations about escalating behaviours become evident and require direct intervention. There are threats to suicide or self-harm present. The threats are recent, repeated and/or specific. There may be other risk factors present, including stalking, sexual assault, change in behaviours. Non-fatal strangulation has occurred. Likelihood of homicide escalated and/or imminent. Formally structured coordination and collaboration of service and agency responses is required. Involvement from statutory and non-statutory crisis response services is required (including possible referral for a RAMP response). This includes risk assessment and management planning and intervention to reduce or remove serious risk that is likely to result in lethality or serious physical or sexual violence. Adult victim survivor self-assessed level of fear and risk is high to extremely high and safety is extremely low. |

||

Supporting your assessment

The above table helps you analyse the information you have gathered through your intermediate risk assessment process.

However, the Intermediate Assessment Tool is just one resource you can use to determine the level or seriousness of risk of the person using violence.

You should use your Structured Professional Judgement and your professional experience, skills and knowledge to support your decision-making processes on the level of risk and your risk management actions.

3.5.4 Determining seriousness or level of risk

The model of Structured Professional Judgement provides a framework for gathering and analysing information to assist you to determine the level or ‘seriousness’ of risk.

This includes information about victim survivor lived experience and self-assessed level of risk, the presence of evidence-based risk factors including patterns of behaviour and intention to use violence, and experiences of structural inequality that impact on the person’s risk and capacity for safety.

When working with a person using violence, determining the level of risk requires you to analyse all information related to:

- risk factors (static and dynamic)

- the perpetrator’s behaviours, presenting needs and the background to the circumstances that brought them to the service system

- the pattern, history and intention for using family violence.

These elements, combined with an understanding of the effect their behaviour has on adult and child victim survivors, will assist your decision-making processes throughout intermediate risk assessment and risk management.

Static and dynamic risk factors

Risk factors are recognised as static or dynamic. This reflects how much they are able to change (present/not present, frequency, escalation).

Some risk factors are ‘highly static’, such as history of violence and prior behaviours, as their presence does not change.

Some are ‘highly dynamic’, such as recent separation, impending court hearings and alcohol and drug use, as their presence can change risk rapidly.

Some dynamic risk factors are more stable in nature, in that they may take longer to change, such as beliefs and attitudes.

Both static and dynamic risk factors contribute to assessing and managing family violence risk.

They can also inform a discussion with the person using violence about safety planning, if appropriate (refer to Responsibility 4).

Remember

It is unlikely you will be able to accurately determine the severity, frequency, change or escalation of risk from intermediate risk assessment conversations with the person using violence alone.

Information sharing is a critical input to your understanding of risk.

This will support you to more accurately determine the level or seriousness of risk.

You should proactively seek risk-relevant information from other services and professionals working with the person using violence or victim survivor/s to inform your assessment.

Understanding the concepts of severity, frequency, change or escalation of risk will support you to determine the level of family violence risk.

This is particularly important when analysing information shared by the victim survivor or another service that has undertaken a risk assessment with the victim survivor.

For further information about victim survivor–focused risk assessment, refer to victim survivor–focused Responsibilities 3 and 7.

3.5.5 Reviewing risk assessment over time

The intermediate risk assessment process is ongoing and should occur throughout your ongoing contact or engagement with the person using violence.

When you decide on the level or seriousness of risk, this reflects risk at ‘a point in time’.

Your risk management strategy should be a direct response to the determined level of risk. It should address the risk factors, behaviours, needs and circumstances underpinning your rationale for risk level (developing a risk management strategy is outlined in Responsibility 4).

Risk is dynamic and can rapidly change or escalate over time.

Ongoing risk assessment requires you to assess and monitor the person using family violence’s presentation and engagement, and presenting needs or circumstances related to family violence risk.

Risk factors will change and may escalate or de-escalate depending on the circumstances of the person using family violence.

Where possible, ongoing engagement ensures you can identify change or escalation of risk and behaviours.

You should take every engagement (such as conversation or observation), non-engagement (where the person declines to engage), disengagement (where person discontinues engagement with your service), as well as historical and current information into consideration when assessing the risk presented by the person using violence.

You should regularly revisit and build upon the prompting questions outlined in the Assessment conversation model with the person using violence. This helps you to understand changes in presentation and risk, and to gain a deeper understanding of the person’s pattern and intent to use family violence.

You should also regularly and proactively seek and share information with others to inform and update your risk assessment.

If you identify changes in a person’s behaviours, needs or circumstances, or gain further information related to risk, apply Structured Professional Judgement to determine the ‘point in time’ level of risk.

You can record this information using the Intermediate Assessment Tool and compare with previous risk assessments to identify patterns and changes to risk over time.

The key to determining seriousness of risk is to understand how risk changes or escalates over time.

If you identify that no change has occurred, you can continue to observe and monitor narratives related to risk. This will allow you to identify patterns of coercive control and the person’s intent or choice to use violence.

Remember, no change or no reported change can also indicate risk.

Factors that impact the dynamic nature of risk presented by the person using violence can include:

- patterns of family violence behaviour

- family violence intervention orders and family violence safety notices, including when recently made, served, varied or expired

- events such as high-profile sports, religious or public holidays or school holidays (if applicable)

- court matters (generally) and Family Court matters pending, being resolved or remaining unresolved – particularly if related to divorce settlement, parenting orders/arrangements and change to arrangements

- emotional distress linked to relationship breakdown or parenting issues/changed arrangements (e.g. outside of court orders, above), particularly around holidays, birthdays or other significant events

- pregnancy/new birth for the adult victim survivor

- housing or homelessness, or change in accommodation or accommodation needs (such as related to family violence intervention order exclusion conditions)

- change in employment or financial situation/instability, disengagement with education

- alcohol or drug use, problematic gambling, and change in behaviour or access to these

- isolation or disconnection from family and/or friends, community

- isolation related or due to cultural or religious/faith-based beliefs.

Change in the relationship or power dynamics can be reflected in a change or escalation of the person’s use of family violence.

Change outside of their control, such as change in circumstances or system interventions, may relate to retaliation and co-occurring escalation of family violence risk and general violent behaviours.

Note

It is likely the actual risk level is higher than you identify from your conversation, disclosure or observed narratives in a session with a person using violence.

This is because people rarely disclose more serious risk behaviours and incidents, often due to shame, denial or guilt.

This is not uncommon across many forms of engagement and counselling practices when client/worker relationships are forming.

Minimising, denying and blaming are common narratives. It takes time and skill to shift the narrative to one of taking responsibility and accountability.

It is important that you manage any uncomfortable feelings you have about this. Your communication should remain balanced, as this will support your engagement with the person using violence and increase the likelihood of their ongoing engagement with the service system.

3.6 Recognising invitations to collude

Collusion occurs when professionals, organisations and the service system act in ways that reinforce, support, excuse or minimise a person’s use of family violence and its impacts.

It reduces your own and the service system’s capacity to keep the person using violence engaged, in view and accountable for their behaviour, and to keep victim survivors safe.

All professionals have a responsibility to understand the drivers, contributing factors and presentations of family violence across different relationships and communities (refer to section 12 in Foundation Knowledge Guide).

This knowledge will help you recognise and respond to invitations to collude throughout your practice.

In your engagement with people using violence, you may hear statements that invite you to collude.

These are often identified in narratives, outlined in detail in Responsibility 2, including narratives:

- specific to the type of relationship the person using violence has with the victim survivor, such as narratives about intimate partners may vary to narratives about children, family members or people in their care

- that deny, minimise, justify or blame-shift use of coercive control and violence

- that position the person using violence as a victim (victim stance) to further minimise or justify their use of violence

- that the person is entitled to use coercive control or violent behaviour

- that represent myths and stereotypes about family violence, identity, culture, faith and age.

Some people who use violence seek collusion through their narrative and description of their needs or circumstances. This helps them to avoid responsibility for their family violence behaviour, and to deny, minimise or justify their use of violence and control. Some narratives can sound convincing.

The person using violence may be very confident in expressing their justifications, denial and/or minimisation about their behaviour, their rigid beliefs, or use of inflammatory remarks about victim survivors. They may believe these will go unnoticed or unchecked, particularly if they have not been responded to in the past.

Some invitations to collude may be deliberate, considered and calculated. The person using violence may attempt to manipulate you to get you on side or instil doubt in you. This is usually preceded by a set of tactics, where the person using violence seeks to enlist your support for their perspective over time. For example, they may first seek your agreement that their life situation is ‘challenging’, that they are acting ‘reasonably’ given the circumstances they face, and that any ‘disagreement’ with the victim survivor is understandable.

You may be colluding with a person using violence when you accept this narrative as true and respond using terms such as ‘relationship issues’.[23] You may continue to collude when you base your professional decisions only on the perspective of the person using violence. This means you accept the person’s narrative on face value without considering the experience of the victim survivor.

You may adopt terms such as ‘mutual violence’ to describe the situation in case conference discussions. Your risk management actions and interventions may actually increase risk for the victim survivor. Refer to Section 3.9 for guidance on predominant aggressor and misidentification.

Be aware that:

- People who use violence are poor predictors of, or intentionally minimise, the level of risk they present to others.

- It is uncommon for a person using violence to be open and honest about their patterns of coercive controlling behaviours or violence in the initial stages of engagement.

- People who take little or no responsibility for their use of family violence may be heavily invested in inviting you to collude with them by agreeing or empathising with their story.

- People who use violence often make attempts to avoid acknowledging their use of violence. If they do, they often couch disclosures in narratives that seek to minimise the impact of their behaviour or blame something external for their actions (such as work stress, the behaviour of the victim survivor, or alcohol use).

There are two broad obstacles to a person using violence taking responsibility for their behaviour:

- feelings of shame about their actions

- using deliberate attempts to minimise, deny, shift blame or remove their own responsibility in order to maintain power and control over victim survivors.

Often, a combination of these two obstacles occur simultaneously for the person.

3.6.1 Recognising collusion based on a victim stance

People who use violence often present with a victim stance.

They may adopt a victim stance when they don’t recognise their behaviours as family violence. This is particularly the case if they believe physical violence is the only form of family violence and when their use of other behaviours has resulted in police or service intervention.

‘Victim stance’ is an emerging and complex concept, arising from descriptions of professionals in direct practice in specialist perpetrator interventions.

Responsibility 2 outlines narratives related to a victim stance.

The headings below provide more information on the contexts in which people using violence may adopt a victim stance.

The person has past or recent experiences of trauma

A person using violence may adopt a victim stance when presenting (legitimately) as a victim of violence, trauma, experiences or systems. They may do this without taking responsibility for, or even admitting to, the harm they have caused.

When questioned about their own use of violence or control, the person may respond with avoidance and redirection, shifting the focus of conversations to speak to their own experiences.

This may include their own experiences of family violence and abuse, particularly as a child.

It can be difficult for a person using violence to talk about their own behaviour or beliefs and attitudes that underpin their use of family violence.

For some, changing the conversation to their victim history and using statements such as, ‘I'm a victim, too’, shifts focus away from themselves and relieves any emotional discomfort.

When professionals accept this invitation to move the conversation away from the person’s use of violence, the person learns that strategies of avoidance and redirection work. They do not need to feel the discomfort or shame attached to their behaviour or take personal responsibility for their actions.

The person adopts a victim stance as learned behaviour to reduce responsibility

For some people using violence, adopting a victim stance may be a learned behaviour.

The person may have learned over time that diverting attention away from their behaviour by any means necessary works, and they continue to do so to purposefully avoid responsibility.

Taking a victim stance may be a motivated, purposeful way to hide their responsibility and deflect the conversation.

This is particularly the case where deflection allows them to blame the real victim survivor. They may accuse the victim survivor of being a perpetrator and create the conditions for misidentification.

The person perceives themselves as a victim of the system

This may arise from previous encounters with the justice, police or social services systems. This may be their own experience or that of people they know. This experience may be of real or perceived barriers, structural inequality or systemic and individual discrimination.

Experienced practitioners report that people who use family violence disclose trauma histories to strengthen their victim stance.

This allows them to push back on or avoid a professional’s attempts to initiate a difficult conversation about their own violent behaviour.

A victim stance may also arise as a response to the system itself.

When people are arrested or issued with court orders, they may feel as if they have been wronged.

One of the things people using violence do to maintain abusive patterns is normalise these behaviours. Therefore, when the system intervenes, they often perceive this as an unjust intervention.

If your service engages with mandated clients, this is likely to be familiar to you.

Autonomy is a basic psychological need[24] – when autonomy is taken away, you should expect some sort of resistance. The victim stance is just one example of this.

3.6.2 Recognising collusion through systems abuse

People who use family violence may seek to manipulate services and systems and use them as a ‘weapon’ against victim survivors.

This is sometimes called ‘systems abuse’. Reflect on guidance in Section 11.1.2 and 12.1.18 of the Foundation Knowledge Guide. This is sometimes referred to as ‘systems abuse’

Systems abuse can include:

- vexatious applications to courts (which are particularly prevalent in family law proceedings)

- controlling victim survivor access to support services if the person using violence has caring responsibilities

- malicious reports to statutory bodies such as police, health services, family services and Child Protection.

Systems abuse occurs within the broader context of coercive control. It is a strategy to maintain control over a victim survivor or cause further harm.

Systems abuse can have extreme and long-term impacts on victim survivors. Section 12 in the Foundation Knowledge Guide includes a range of examples across relationships and communities.

Systems abuse can also lead to misidentification of people using family violence and victim survivors, particularly where the person using violence adopts a victim stance that goes unnoticed or unchallenged.

Women are more likely to be misidentified as the person using family violence than men,[25] and evidence suggests this is a particular risk if victim survivors require interpreters, have a disability or a mental illness, or are Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander.

Myths and stereotypes about the presentation of victim survivors and binary gender norms also contribute to misidentification within LGBTIQ relationships.

Systems abuse can occur when people who use violence target the victim survivor’s identity or experiences in their methods of coercive controlling behaviour. This may also increase the likelihood of misidentification of a perpetrator/predominant aggressor.

This has the effect of exacerbating or exploiting existing structural inequality, barriers and systemic and individual experiences of discrimination. In doing so, they further their own position, undermine the victim survivor and continue to perpetrate violence.

You should be aware that a person using violence may be intentionally manipulating you, your service or parts of the system to further harm or control a victim survivor.

This use of power and coercive control aims to invite you to collude with their position or intention for using violence against the victim survivor.

Remember

Accepting invitations to collude increases the risk to victim survivors and reduces your capacity to appropriately engage in risk assessment and risk management.

If you believe you are being invited to collude with a person using violence, you can seek both internal and external support by:

- talking with senior co-workers, your supervisor or team leader for support in your response

- seeking secondary consultation with a specialist perpetrator intervention service.

3.6.3 Key practices to minimise the risk of collusion

For professionals working with a person using family violence, it can be complex and challenging to balance a trusting, respectful working relationship with non-collusive and accountable practice.

When attempting to respond without colluding through agreement (compliant collusion), you must also be equally aware of the challenges of responding without colluding through argument and confrontation (oppositional confrontation).

In both response types, you risk acting in ways that reinforce the person’s position of not taking responsibility for their use of family violence.

You may be concerned that engaging proactively with people using family violence signals implicitly or explicitly that you endorse their behaviour.

However, staying engaged with a person using violence allows you to assess and manage risk.

If you feel your professional decision-making process is being compromised by collusion, you should seek secondary consultation with a specialist service working with people using violence.

You can also seek advice from other professionals, such as mental health or alcohol and drug services, who work with the person using violence to identify if they are also being invited to collude.

If the person using violence is Aboriginal or identifies as belonging to a diverse community, you can seek consultation with professionals working in targeted and specialist community services. This can help ensure you do not discount legitimate experiences of discrimination and trauma while taking a balanced approach to engagement.

Be curious and invitational – use professional curiosity

Ask questions and be open to hearing the narrative and understanding the behaviour of the person using violence.

It is important, as outlined in Responsibility 1, to build trust and rapport. This will enable a person using violence to continue to engage with your service.

Key practices to balance safe and respectful engagement while minimising the risk of collusion include:

- keeping the victim survivor’s experience and the effects of the violence as your central concern. You can do this by listening for information that could be relevant to risk and indicate the impacts on victim survivors

- being alert to the potential of implicitly or explicitly endorsing violence-supporting narratives or behaviours of the person using violence

- intentionally listening, taking an invitational but objectively analytical approach. This can help you to avoid the risk of inadvertently supporting minimising, justifying or blame-shifting narratives of a person using violence

- avoiding confrontation with the person using violence. This helps you to reinforce help-seeking behaviours and model non-confrontational problem solving.

You should be aware of the conditions that contribute to family violence perpetration as outlined in Responsibility 2 and hold these in mind throughout your engagement.

Applying intersectional analysis, outlined in Foundation Knowledge Guide and in Section 3.3 above, can enable you to understand the person’s multi-layered identity, circumstances and life experiences.

Using a balanced approach to engagement

The table below illustrates three styles of engagement professionals often use when working with people who use violence:

- compliant collusion

- a balanced approach

- oppositional confrontation

The style you adopt when engaging with people using violence can affect your capacity to build rapport and trust, keep them engaged with your service, and encourage responsibility-taking.

At times you may adopt a different style in response to invitations to collude.

- Compliant collusion occurs when you become invested in the person’s narrative as it is presented, which is likely to reinforce and validate the beliefs or attitudes of the person using violence.

- Using a balanced approach means you are aware of the purpose of their engagement with your service to address a need, you understand that they may disclose or share information with you that indicates they are using family violence, and you can hold these two narratives in mind when working with them in a way that is non-collusive.

- The oppositional confrontation approach is when you use your position, power and knowledge to argue with the person using violence or oppose their invitations to collude. This emulates the power and control of the person using violence, and it can both increase risk and reinforce the message that this type of behaviour is rewarded with more power. Oppositional confrontation occurs when your judgement, assumptions, beliefs or agenda override your risk and safety engagement practices, and you use an aggressive tone, presentation or behaviour that mirrors that used by the person using violence in their relationships. While your intent may be to ‘hold the person using violence to account’, it can increase risk to the victim survivor and push the person further away from personal accountability and change. Using an oppositional confrontation approach reinforces their behaviour as being appropriate and acceptable.

You should respond using a balanced approach to avoid reinforcing behaviour that rewards the use of power over people, while also avoiding validating the person’s violence-supporting narratives.

Note

There is no one way to have a conversation with a person using violence about their needs, circumstances, relationships and risk to inform a family violence risk assessment. You should build your style and presentation into the process.

Reframe the prompts in the Assessment conversation model to align with your own approach, engagement skills, competency and personality. This is important, as a genuine, enquiring and curious approach will build your professional relationship and rapport with a person using violence.

One approach to feel confident in your engagement is to be guided by the responses from the person using violence and use follow-up questions.

It is important to trust your skills, knowledge and experience in the engagement process.

This will support your capacity to elicit answers that build your understanding of the person’s story in a safe and respectful way.

Table 2: How to respond to invitations to collude[26]

|

Compliant collusion |

A balanced approach |

Oppositional confrontation |

|

Engagement occurs and the conversation feels friendly, personal and easy. You hear their narrative and there is little challenge and conflict, which can lead to validating their experiences and narrative. |

You engage with the person using violence, acknowledging their needs and increasing their readiness to engage with the services you offer or provide. You know these services will actively contribute to reducing risk associated with family violence and provide feedback about how these may improve other aspects of their life, like relationships with family members. These sessions may be difficult because the person using violence experiences internal conflict, vulnerability or shame, but may not necessarily name these feelings at this point. |

You use information from others to tell the person you know about their use of family violence. You use information to ‘catch them out’. The person notices you are judging them for their use of violence, either through what you say or your body language. They respond to you with the same level of opposition, which you experience as ‘resistance’. |

|

You join in with the person’s views about the behaviours of others (such as perceived ‘provocation’ to use violence or blame-shifting to focus on another person’s behaviour), and the impact of that behaviour on them. |

You use professional curiosity to ask questions to understand the relationship and context of the behaviours the person using violence is listing. You invite them to consider what they are bringing into the situation they describe and make gentle suggestions to challenge themselves about how they would like to interact differently in this situation. You can acknowledge a person’s experience of violence without colluding with narratives that shift blame. |

You confront the person using violence with their wrongdoings, and/or tell them they are probably the cause of someone else’s behaviour towards them. |

|

You over-empathise when the person talks about themselves as a victim of others or their circumstances. |

You listen to the person using violence’s description and use professional curiosity to gather information about the situation and the potential risks they present. You ask questions about whether they feel fearful or unsafe from any other people in the family.[27] If they state they are not fearful for themselves, you can explore their capacity for empathy about their behaviour, circumstances or capacity for empathy towards the other person who may be affected in the situation. |

You don’t empathise at all or tell them they sound like they are actually a person using family violence. |

|

The person using violence feels you understand them better than their partner or family members. You feel liked by the person using violence and less anxious about your engagement. |

The person using violence may come to value and respect your help. |

The person using violence dislikes you and is unlikely to engage with you. They may disengage from the service and other services. The person using violence becomes visibly angry or upset. They may become verbally aggressive or completely withdraw from the conversation. |

Remember

The person using violence will disclose objective indicators of risk and risk factors during assessment of their presenting needs and circumstances, such as employment, use of alcohol or drugs and mental health.

They may also use narratives related to these presenting needs and circumstances that invite you to collude with their minimisation or justification of their use of family violence.

Applying non-collusive practice means you recognise these invitations, do not respond with agreement or argument, but instead use professional curiosity and a balanced approach to explore the person’s narrative and use the information to inform your risk assessment and risk management.

If a person using violence invites you to collude, this is risk-relevant information. You can record these invitations as an observed narrative or behaviour in the Intermediate Assessment Tool in Appendix 3.

3.7 Opportunities to engage and monitor risk over time

Family violence is rarely a single ‘incident’.

It is usually a pattern of coercive and controlling family violence behaviours over time.

However, any disclosure of family violence or an identified ‘incident’ is an opportunity to engage the person using violence in the service system.

There are key points in time[28] following an ‘incident’ where a person using violence may come into contact with services.

These points in time present opportunities to assess risk and support people who use family violence to stabilise their needs and circumstances and enhance their capacity to change their behaviour.

Time-based opportunities can include:

- following first disclosures in the course of their initial engagement (such as alcohol and other drug use or related to a court order)

- over the course of your ongoing professional relationship with the person to address presenting needs.

An ‘incident’ may be police-attended (or not), be followed by a new intervention order and/or disclosed as part of the person’s engagement with you.

The table below provides an overview of opportunities for non-family violence specialist professionals to engage based on timeframes following an ‘incident’ or disclosure.

This is generalised information and should be used as a guide only.

This will inform your risk assessment of the person using violence and support you to tailor your responses to each individual presentation (refer to Responsibility 4 for further information about time-based risk management responses).

Table 3: Key timeframes for assessing and monitoring risk after disclosure or you become aware of a family violence incident

|

Timeframe after you become aware of family violence |

Purpose of engagement, risk assessment and monitoring |

|

Immediately following, up to two days |

Contact at this time may have resulted from police, Child Protection, health or mental health service system response – this will affect how a person using violence moves through the service system, re-presents to services, or engages with you about their needs or family violence risk behaviour. In this timeframe, your risk assessment actions can include:

|

|

Within two weeks |

The person using violence may be excluded from the home (temporarily or for an extended period). This time may enable them to adjust, or conversely resist, new living arrangements and any changes in their relationship, such as separation. If they do not adjust to the new arrangements, they may return to the family home in breach of a family violence intervention order. They may believe things can return ‘to normal’ or express motivation to work towards this. They may have increased motivation to engage with services about family violence risk or related behaviours, parenting or other needs or circumstances. During this period, they may have support needs such as crisis mental health services. Proactive, timely and safe engagement can increase the likelihood of engagement about the incident and acceptance of supports offered. In this timeframe, your risk assessment actions can include:

|

|

Two to three weeks |

The person using violence may acknowledge some aspects of family violence or related behaviour, reflecting an increased sense of shame or guilt. You may identify attitudes towards compliance or non-compliance with any police/court interventions or family violence safety notice or intervention order conditions. In this timeframe, your risk assessment actions can include:

|

|

One to four months |

Your engagement can support the person’s capacity for change while monitoring risk over time by:

In this timeframe, your risk assessment actions can include those outlined in ‘Two to three weeks’, as well as:

|

|

Ongoing |

Where appropriate to your professional role, keep the person using violence engaged with your service to monitor for change or escalation of family violence risk. Identify the impact of your support to stabilise the person’s needs and circumstances on their level of risk. In this timeframe, your risk assessment actions can include those outlined in ‘One to four months’, as well as:

|

3.7.1 What to do if the person using family violence disengages

Disengagement enables the person using violence to be invisible to the service system (not in view) or not accountable, often leading to:

- change or escalation in frequency or severity of family violence. This may relate to changes in needs and circumstances related to risk, such as increased use of alcohol or drugs, housing instability, change in mental health

- increased risk for victim survivors and family members. The inability of services and systems to monitor for change or escalation in risk reduces the likelihood of timely and appropriate responses to new family violence ‘incidents’