This section contains a selection of case studies and guidance to introduce you to new MEL approaches and explore how they are being implemented in practice with local communities. While a range of approaches are covered, this section is unlikely to provide enough detail to help you determine whether or not they are appropriate for your particular context. Where possible, additional resources are included to help you better determine what is applicable to your work.

Monitoring Example: Latrobe Valley Authority

Who is this case study about?

This case study is about the Latrobe Valley Authority (LVA); a place-based approach that intentionally partners with the local community to address complex challenges and support economic and social development across the Latrobe Valley. This spotlight focuses on LVA’s implementation of an impact log for staff to measure change and see the outcomes of their work.

What tools does it feature?

The case study features an impact log, which is a low-burden monitoring and evaluation tool used to capture reflections and gauge the influence of a program or initiative.

Why has this case study been featured?

The impact log continues to help LVA to record direct responses from the community about their work and map this over time in an efficient manner. It also helps them to capture impact for communication to executive leadership and ministers.

Where can I find more information to help me apply these tools?

Case study

Introduction

An impact log is a low-burden tool used to collect

day-to-day data to capture outcomes as they occur. An impact log works as a simple vessel for organised data. Those submitting data can respond to a few standard questions in a survey or enter data directly into a table (such as on Excel). LVA regularly use an impact log to support their MEL work. Given the complex, wide reaching and collaborative nature of their work, an impact log offers a way of capturing emergent outcomes in real-time, from across their numerous projects and programs.

LVA’s impact log is mapped alongside their behaviour and system change framework, which trains staff to think evaluatively and be alert to behaviour change occurring at a high level. LVA staff use this framework to guide their entries. The impact log is incorporated into the day-to-day work of LVA staff and stakeholders, allowing for real-time data and responses to be collected. Although designed to be an internal tool, where possible LVA staff make their entries reflective of community voice, by entering information drawn from conversations with community members and capturing reflections of those in the field.

LVA promotes the impact log by reminding staff about the tool in meetings, and regularly touching base with their funded bodies to share stories of growth and impact.

Application

The impact log has added value across the following areas for LVA:

- Learning and improvement: Able to use the information recorded to inform decisions about their work (enhance what is working well or improve certain practices).

- Identify and communicate early signs of change: Acts as a central log for stories of change and mindset shifts that can be leveraged for communications purposes as required – including for government stakeholders and the community.

- Lay foundations for rigorous evaluation studies down the track: Comprehensive studies can be conducted to substantiate and validate outcomes recorded in the impact log. This analysis can in turn contribute to learning, storytelling and overall accountability.

- Capturing community voice: Allows people to share their experiences firsthand, enabling the community to be the storytellers of their own experience.

- Coordinating diverse viewpoints: Creates the opportunity to have a central repository for many contributions, including the perspectives of their various partners working in place.

Reflection/impact

The impact log has proved to be a rich tool for LVA, allowing them to draw valuable insights about the impacts of their work. Despite this, some challenges have emerged, including:

- Driving uptake: Generating momentum for staff to contribute to an impact log can be challenging, as it is an ongoing process, and can require time investment and a level of interpretive effort. One way that LVA has sought to drive uptake is by using innovative ways to prompt staff to access the log, including by developing a QR code that links directly to the survey.

- Capability and needs-alignment: In order for impact log entries to be reflective of community voice, staff need to have insight into what is relevant and engaging to community. Building trust and investing in partnership work are two ways to do this, however they both take time. Further to this is the challenge of aligning the needs of those using the tool (LVA staff) with broader evaluation purposes. Questions need to be carefully framed so that they resonate with staff while also supporting evaluation goals and additional training may be required to ensure fidelity of use.

- Privacy and accessibility: An impact log can at times collect sensitive information, so good privacy controls are important. Accessibility is also vital, so that staff can easily contribute to and review the log. Finding a platform that is easy to use and accessible across a range of levels, while also meeting government security standards and allowing for detailed analysis to be conducted in the backend, is an ongoing challenge.

LVA impact log questions

Why?

We often struggle to capture and understand the less tangible impacts and changes associated with the influence of our work.

What?

A story-based tool that seeks to capture place-based examples of changes across system.

How?

Eyes and ears: record conversations or evidence that suggests that the system may be changing.

Which area(s) has the impact changed?

- Innovation (production, processes or services)

- Knowledge (research or information)

- Relationships

- New practices

- Behaviours or mindsets

- Resources and assets flow

- Value/benefit for partners, community or region

- Organisational structures

- Policies

What is the impact?

(what changed)

How did this change happen?

(what contributed to this change)

Level of contribution?

- The change would not have occurred but for the contribution made

- It played an important role with other contributing factors

- The change would have occurred anyway

Who contributed to this change?

Who benefits from the change?

- Individuals

- Group/network

- Organisation/industry

- Community

- Region

- State

Do you have any supporting evidence?

Evaluation Example: Contribution Analysis study in Logan Together

Who is this case study about?

This case study profiles ‘contribution analysis’ which is the evidence-informed process of verifying that an intervention, way of working or activity has contributed to the outcomes being achieved. Approaches for evaluating contribution range from light to rigorous, and this example is the latter. Contribution analysis plays an important part of measuring social impact—tracking outcomes alone will not provide a strong impact story.

What tools does it feature?

This case study outlines the steps undertaken for a contribution study. The study utilised quantitative and qualitative data, theory of change, contribution assessment and strength of evidence rubrics. The study was undertaken by independent evaluation specialists.

Why has this case study been featured?

It is an example of a rigorous approach to assessing contribution where attribution cannot be ascertained quantitatively.

Where can I find more information to help me apply these tools?

Case study

Overview

During 2021, the Department of Social Services (DSS) commissioned a contribution analysis on the Community Maternal and Child Health Hubs in Logan (‘Hubs’). The study aimed to evaluate the contribution of the Collective Impact practice on the health outcomes achieved.

The Hubs aim to increase access and uptake of care during pregnancy and birth for Logan women and families experiencing vulnerability. They cater for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, Māori and Pacific Island women, young women under 18 years old, culturally diverse women, refugees, and women with significant social risk. The Hubs and the supporting Collective Impact initiative Logan Together are based on the traditional lands of the Yugambeh and Yuggera language speaking peoples in the Logan City area, near Brisbane.

The study was undertaken by Clear Horizon, in close partnership with Logan Together and DSS. The study is one of the first of its kind in the Australian context, and provides a well-evidenced and rigorous assessment of the role of Collective Impact practice.

How the study was done

The methodology was informed by Mayne’s Contribution Analysis and used an inductive case study approach. Determining the causal links between interventions and short, intermediate, and long-term outcomes was based on a process of establishing and evaluating a contribution hypothesis and building an evidence-informed contribution case.

The methodology required first evidencing the outcomes achieved and then investigating the causal links between the ways of working and activities with the results. The key steps included:

- Developing a contribution hypothesis using a theory of change approach

- Data collection and reviewing available quantitative and qualitative data

- Developing an evidence-informed contribution chain and assessing alternative contributing factors

- Developing and applying rubrics for rating contribution and strength of evidence

- Conducing verification and triangulation.

Benefits

The findings have been useful for DSS and Logan Together to demonstrate the effectiveness and impact of Collective Impact practice. It has helped governments demonstrate the contribution of the Collective Impact practice, which was verified to be an essential condition for the health outcomes being achieved.

The contribution analysis showed that the Hubs, and subsequent outcomes (including clinically significant outcomes for families involved), would not have happened without the Collective Impact practice.

Challenges

One of the challenges of a rigorous contribution analysis is that there are multiple impact pathways by which interventions can influence outcomes, and many variables and complexities in systems change initiatives.

Detailed contribution analysis take time, stakeholder input, and resourcing to ensure rigour and participatory processes. Communicating the contribution case can also be challenging if the causal chain is long and complicated, and when there are many partners involved.

Keep in mind there are other ‘lighter touch’ contribution analysis tools, such as the ‘What else tool’, that help make this important methodology feasible and accessible within routine evaluation without the need for specialist skills.

Testing and verifying contribution

Using the multiple lines of evidence, a ‘contribution chain’ was developed and tested across different levels of the theory of change. The contribution chain shows the key causal ‘links’ along the impact pathway for an intervention. The simplified steps to evaluating the contribution for the Community Maternity Hubs is shown below.

The data sources included quantitative metrics available from Queensland Health, population-level datasets provided by Logan Together, and a small sample of key informant interviews and verification workshops. Two evaluative rubrics were used in the methodology, one to define and assess contribution ratings and the other to assess the strength of evidence used to make contribution claims.

Contribution chain example, “Community Maternity Hubs”.

- How the collective practice influenced the conditions and changes in the system—and how this contributed to developing the Hubs. This included assessment of the collaborating partners and the different roles they played. Levels of change include:

- Hub intervention and systems changes

- Collective impact conditions, including

- Systems approach

- Inclusive community engagement

- High leverage activities

- Backbone and local leadership and governance

- Shared aspiration and strategy

- Strategic learning, data and evidence

- How the Hubs model and delivery are contributing to outcomes for target cohorts using the Hubs was assessed. Levels of change include outcomes for Hub users and target cohorts.

- Analysis then focused on if the Hubs’ outcomes are contributing to population level changes for women and babies in Logan. Levels of change included population-level changes across Logan.

Challenges and opportunities for economic assessments in complex settings

This section outlines the commonly used methods for economic assessment and outlines limitations of these methods when applied to place-based contexts. It then introduces an innovative approach to assessing value for money that accounts for some of these limitations and presents a key set of considerations when approaching value assessments in place-based contexts.

Commonly used methods for economic assessments

Economic assessment is the process of identifying, calculating and comparing the costs and benefits of a proposal in order to evaluate its merit, either absolutely or in comparison with alternatives (as defined by DJPR). All economic methods seek to answer a key question: ‘to what extent were outcomes/results of an initiative worth the investment?’

- Cost Benefit Analysis (CBA) is a widely used method to estimate all costs involved in an initiative and possible benefits to be derived from that initiative. It could be used to provide as a basis for comparison with other similar initiatives.

- Cost-Effectiveness Analysis (CEA) is used as an alternative method to cost-benefit analysis. It is used to examine the relative costs to the outcomes of one or more interventions. CEA is used when there are constraints to assessing monetise benefits.

- Social Return on Investment (SROI) (PDF, 1,190 KB) uses a participatory approach to identify benefits, especially those that are intangible (or social factors) and difficult to monetise.

Key takeaways

- All methods have challenges and subjectivities. When aiming to consider/assess value for money, be open to using approaches and methods that can best suit your needs.

- When considering value for money of place-based approaches, assessments need to:

- accommodate changing contexts with emergent, unpredictable and complex outcomes

- enable genuine learning with stakeholders throughout implementation

- recognise that sometimes failure is necessary because there is a level of risk and failure in particular project—need to learn from this.

- maintain transparency and rigour around how economic judgements/assessments are made

- involve stakeholders and particularly those who will be affected by evaluation—in the spirit of participatory approaches in PBAs.

Examples of application

Several place-based initiatives have used a mix of qualitative, quantitative and economic methods to determine the extent to which the initiative achieved value for money.

- Maranguka Justice reinvestment in Bourke, NSW (PDF, 704 KB).

Conducted an impact assessment to calculate the impact and flow-on effects of key indicators on the justice (e.g. rates of re-offending, court contact) and non-justice systems (e.g. improved education outcomes, government payments). - The Māori and Pacific Education Initiative in New Zealand (PDF, 3.8 MB).

Conducted a value for investment which included tangible (e.g. educational achievement and economic return on investment) and intangible dimensions (e.g. value to families and communities, value in cultural terms) of value. - An economic empowerment program for women in Ligada, Mozambique (PDF, 2.7 MB).

Used a value for money framework which used a mix of quantitative evidence and qualitative narrative to assess performance. The approach factored intangible values (such as self-worth, quality of life) when measuring impacts. - ActionAid (PDF,1,678 KB).

Developed an approach driven by participatory methods to assess value for money which involved community members in the assessment if value for money.

Limitations of using purely economic methods

Economic assessments can present some challenges including difficulties in:

- monetising social benefits in a meaningful way and in an environment where benefits are evolving and occurring over a long timeframe

- defining value when there are different perceptions of value held by stakeholders involved in place-based initiatives

- addressing equity in terms of the segments of the population who may not have been impacted by the intervention

- ascribing monetary value to a particular pool of funding can be difficult when outcomes are a result of a collective effort

- supporting learnings on factors that influence the effectiveness of a place-based approach in responding to complex challenges.

An innovative method for assessing value for money

There are new methods emerging in this space to counter the limitations of mainstream economic methods such as Julian King’s Value for Money (VfM) framework which brings more evaluative reasoning in to answer questions about value for money.

The VfM framework encourages the definition of value within the context that is relevant to the stakeholders and uses a process to judge what evidence suggests to reach evaluative conclusions about the economic value of an initiative.

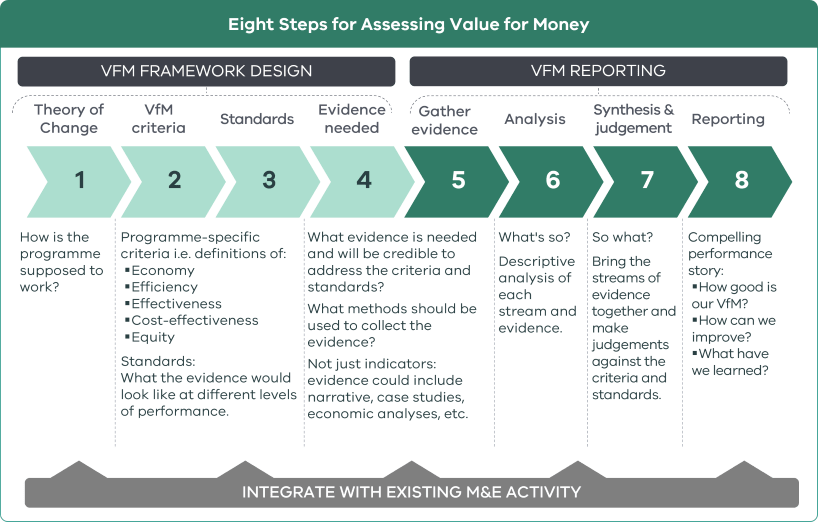

The approach sets out eight steps across the designing, undertaking and reporting of a VfM assessment (see diagram to the right). The approach combines qualitative and quantitative forms of evidence to support a transparent, richer and more nuanced understanding than can be gained from the use of indicators alone.

The VfM framework is embedded within the MEL design for efficiency and to ensure conceptual coherence between VfM assessment and wider MEL work.

Eight Steps for Assessing Value for Money

Source: OPM’s approach to assessing Value for Money (PDF, 2.5 MB) (2018) developed by Julian King and OPM’s VfM Working Group

VfM Framework Design

Step 1: Theory of Change

How is the programme supposed to work?

Step 2: VfM criteria

Programme-specific criteria i.e. definitions of:

- Economy

- Efficiency

- Effectiveness

- Cost-effectiveness

- Equity

Step 3: Standards

What the evidence would look like at different levels of performance.

Step 4: Evidence needed

What evidence is needed and will be credible to address the criteria and standards?

VfM Reporting

Step 5: Gather evidence

What methods should be used to collect the evidence?

Not just indicators: evidence could include narrative, case studies, economic analyses, etc.

Step 6: Analysis

What's so?

Descriptive analysis of each stream and evidence.

Step 7: Synthesis & judgement

So what?

Bring the streams of evidence together and make judgements against the criteria and standards.

Step 8: Reporting

Compelling performance story:

- How good is our VfM?

- How can we improve?

- What have we learned?

Learning Example: The Healthy Communities Pilot - A layered approach to collective learning and protection of community defined data and knowledge

First Nations learning and reflection cycles are embedded in Cultures and worldviews. Learning and reflection is conducted all the time, such as over a cuppa, when driving between places or when having a yarn after an event. Place-based work is dynamic and it is vital to reflect on its progress as a collective (in a more formal manner), and to make strategic decisions as to how to progress forward.

The use of truth telling and First Nations tools such as Impact Yarns continue to be centred in learning and reflection. The Impact Yarns tool provides an approach to gathering truth telling, sharing truth telling, layering collective Community voice and then centring First Nations sense-making and sovereignty for local decision-making. This tool covers all aspects of evaluative practice.

The Healthy Communities a pilot focuses on building community and strengthening culture and kinship with the aim of improved health outcomes and behaviours for First Nations communities. The pilot is led by four Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations (ACCOs); Goolum FM Aboriginal Cooperative, Budja Budju Aboriginal Cooperative, Moogji Aboriginal Corporation and Rumbalara Aboriginal Corporation.

The Impact Yarns tool provides an approach to gathering truth telling, sharing truth telling, layering collective Community voice and then centring First Nations sense-making and sovereignty for local decision making. This tool covers all aspects of evaluative practice.

The evaluation of the pilot embeds First Nations sovereignty and truth telling in the evaluation process by using Impact Yarns. Impact Yarns enables staff, project participants and Community to identify the outcomes/changes that they felt were impactful during the pilot. Local Cultural and data governance mechanisms were set up to guide the collective sense-making process and to engage in First Nations thought leadership to identify which Yarns were most impactful and why.

First Nations Data governance also supports and protects the knowledge that was gathered and shared during the evaluation process. This layered approach to data interpretation, governance and decision-making sought to protect Cultural knowledge and wisdom, and ensure that the narrative of Community and First Nations peoples was well authorised and contextualised.

Learning Example: Go Goldfields

Who is this case study about?

This case study is about the Go Goldfields Every Child Every Chance initiative which is aimed at ensuring every child in Central Goldfields has every opportunity to be safe, healthy, and confident. The case study focuses on the launch of the ‘Great Start to School for All Kids’ (GSTS) project and the learning and reflection cycles throughout its implementation.

What tools does it feature?

Action-oriented learning workshops.

Why has this case study been featured?

The case study shows learning workshops can be central to place-based approaches. In this example, workshops provide a forum for partners to work collaboratively to understand the key problems that needed to be addressed in the Central Goldfields area. They also provide partners the opportunity to develop a plan that ensures the project responds to community needs and adapts to meet the evolving needs of the community, addressing emerging issues as they are identified during project implementation.

Where can I find more information to help me apply this tool?

- Platform C website includes various resources to support learning approaches.

Case study

Introduction

Go Goldfields is a place-based partnership between state and local government, service providers, and the Central Goldfields community. The Go Goldfields partnership is committed to achieving better outcomes for children and families in the Central Goldfields Shire.

In late 2019, the Go Goldfields partnership reflected on the current environment, the most pressing issues facing the Central Goldfields community, and where collaborative, place-based action would make the biggest impact. As a result, the Go Goldfields Every Child Every Chance (ECEC) initiative was formed.

The ECEC initiative is aimed at ensuring every child in Central Goldfields has every opportunity to be safe, healthy, and confident. The initiative brings partners together around five priority areas to help achieve this outcome. The priority areas include:

- Healthy and Supported Pregnancies

- Confident and Connected Parents

- Safe and Secure Children

- Valued Early Years Education and Care

- A Great Start to School for All Kids.

Each year around 120 children in Central Goldfields Shire transition into their first year of primary school. In 2021, there were six centres across the Shire offering 3- and 4-year-old kindergarten with an additional centre coming online in 2022.

Application

In September 2021, Go Goldfields facilitated a ‘Great Start to School’ (GSTS) workshop to launch the work in this priority area. The workshop included a collective reflection on current data and research to inform problem and vision statements for the GSTS Transition Project.

The workshop was attended by 20 stakeholders across allied health, early years education and primary schools. The group identified the following problem statements:

- The system of transition is complicated and vulnerable children and families are not getting the support they need to navigate to progress their children through education

- The service system is not working effectively together to meet the needs of children and their families to support a great start to school.

These problem statements were based on the following challenges:

- high levels of socio-economic disadvantage and vulnerability in families across the Shire

- consistently high number of children starting school with vulnerabilities in their social, emotional, communication, language and physical readiness to start school

- evidence that many children and families need additional support to prepare them for beginning school

- absence of a Shire-wide approach to transition from kinder to school

- uncoordinated and sometimes mismatched communication between schools and kindergartens regarding transition.

Workshop participants overwhelmingly understood the importance of early years education as the foundation for a child’s future learning and agreed to the need for a collaborative and coordinated approach to best support families and set children up for success in relation to their learning and development. This was encapsulated in the vision statement:

Schools, early years centres, social support agencies and allied health work collaboratively and effectively together to support families to enable every child and their family to feel prepared and ‘ready’ for their education journey.

The GSTS Transition Project comprises several components including coaching for early years educators, transition workshops, a governance group and transition plan. These components facilitate engagement and reflection, and build collaborative capability across the Central Goldfields.

The transition workshops facilitate the local service system’s reflections on practice and gather learnings gained throughout the implementation of the GSTS Transition Project. Output from the workshops inform the development of the GSTS Transition Plan. The GSTS Transition Plan is endorsed and enabled by the GSTS Governance Group. The GSTS Governance Group acts as a forum for collaborative leadership and decision making to guide the GSTS project delivery, authorise and enable practice developed in the Transition workshops.

Reflection/impact

The GSTS initiative is an example of a place-based approach that has embedded learning and reflection cycles into the design and implementation of the projects that form part of the initiative. The learning and reflection cycles embedded within the project components, have ensured that the actions taken as part of the response are informed by the evolving needs of the community and emerging knowledge and issues, identified during the implementation of the GSTS Transition Project.

Learning Example: Community Revitalisation

What is this case study about?

This case study is about the Community Revitalisation initiative funded by DJPR and supported by the delivery team within the Place-based Reform & Delivery branch.

Community Revitalisation is a place-based approach that operates in five Victorian communities, bringing together communities, their local leaders and government to design approaches to improve economic inclusion that are responsive to local needs and aspirations.

In particular, the case study focuses on the journey that the team has been on to adopt a learnings approach in their work with Community Revitalisation sites.

What tools does it feature?

It features a learnings-oriented approach which includes a range of reflective practices.

Why has this case study been featured?

The case study provides an example of how a learnings-oriented approach helped to build trust between government and sites by breaking down traditional power dynamics and demonstrating that government is willing to listen. It is therefore highly relevant for a government audience.

Case study

Introduction

Government stakeholders tasked with supporting place-based approaches must take an adaptive approach in order to support the local priorities of place-based approaches.

In the case of Community Revitalisation (CR), the Delivery arm of the Place-Based Reform and Delivery (PBRD) branch in DJPR plays a key role in the initiative, showing up as a key partner of CR and as an intermediary role between state government and the community, with work ranging from internal advocacy, capability support to project management.

The PBRD team have adopted a learnings-oriented approach in their CR work in order to continue to improve the CR initiative and the role of government within it.

Application

As part of their commitment as learning partners, the PBRD team employ a number of learning processes. These processes support effective implementation of CR and are outlined below.

- Quarterly Learning Forums with all CR sites to support collaborative design and decision-making and drive effective CR delivery – PBRD members co-develop the agenda and are active participants in the forums.

- High frequency team reflections (weekly/fortnightly) within the delivery arm of PBRD to identify and respond to enablers, challenges and risks.

- Less frequent (monthly/quarterly) reflection points with the policy and reform arms of PBRD and other branches in DJPR to enable on-the-ground learnings to inform policy reform approach.

- Evidence-informed expansion of CR and refinement of guiding model – PBRD conducted semi-structured interviews and thematic analysis within their team and with key partners to explore initial learnings. The subsequent establishment of new Community Revitalisation sites was informed by these learnings, while allowing for an iterative review of the theoretical model underpinning CR’s systemic focus.

- Participation in peer-to-peer learning forums on a national scale - PBRD participated in online workshops and shared experiences about CR with the Federal Government’s Department of Social Services Place-Based branch, ensuring that valuable insights are shared across contexts on a national scale.

Reflection/impact

Based on the articulation of challenges and enablers for this work, the team identified the following capabilities, mindsets and resources that support a learnings-based approach:

- dedicated resources that bring learning practises front and centre on a regular basis

- mindset to show up in a different way and relinquish traditional government power

- strong supportive culture that ensures people are emotionally and/or psychologically safe

- being able to work cross-disciplines and translate knowledge and language from the theoretical to practical application

- having the authorisation and level of authority to effectively respond to the needs of communities

- long(er) funding cycles to support relationship development and trust required to effectively learn with sites

- placing a greater importance on the value of lived experience and content knowledge at sites.

Updated