Designing place-based approaches

Place-based approaches are not for the faint-hearted - they require the right mix of capabilities, mindsets, policies and resources from both community and government.

All successful place-based approaches share a commitment to collaboration and shared outcomes. But in practice, initiatives use different models, methodologies and strategies depending on the local context.

Every place-based approach is, by definition, unique to the place it is targeting

Place-based approaches share common characteristics that guide their design and implementation - they:

- respond to complex, intersecting local drivers that require a cross-portfolio and sectoral response

- develop a shared understanding of local context drawing on a broad range of evidence, from data to research to lived experience and local knowledge

- are based around shared outcomes that reflect locally agreed priorities and unite local stakeholders

- embed deep engagement and collaborative governance structures that engage across sectors and with a diverse cross-section of the community

- are implemented through shared action, with an iterative approach and progress monitoring that supports continual learning

- apply formal approaches to evaluation to enable accountability and guide strategy

However, how partners want to (and are ready to) work will be different in each case.

This section will unpack some of the differences that arise when designing place-based approaches and will require consideration by government when considering or embarking on a place-based initiative.

This section will explore:

|

Different levels of readiness

Place-based approaches work best when communities and government share the right capabilities, policies, mindset and intent. Their success relies on shared outcomes and the strength of relationships.

To work together in a place-based approach, community and government need to be ready or willing to build readiness.Readiness can be gauged by looking at factors such as:

- Leadership

- Government and community leaders with connections, knowledge and influence who are willing to apply their resources to an issue and ‘model the message’ by collaborating.

- Connections

- Across community and government, existing relationships between people and organisations are a starting point for mobilising around shared outcomes.

- Mindsets and willingness to learn

- A willingness to work outside of traditional processes and across organisational boundaries; adapt to changing contexts; and continually innovate in pursuit of shared outcomes.

- Existing effort

- Existing programs, policies or actions around an issue or opportunity can demonstrate an ability to mobilise around outcomes and an attitude of awareness and empowerment.

- Knowledge of past efforts

- People who know what has gone before (and can identify what does and does not work in improving outcomes for the local community) are key to ensuring that initiatives build on lessons learnt.

- Resources and skills

- Staff, time, funding, facilities, skills, etc. in the community and within government that can be made available to work towards shared outcomes are a key enabler.

Satisfying all of these conditions is not common, and when working in a place-based way, you always need to start where government and the community are at.

Government can be uncomfortable with the time it takes and the process of sharing influence, control or accountability. Staff often do not have the right mix of capabilities and mindset or feel appropriately authorised to engage effectively.

Communities also might need to build the skills or leadership to stay the course.

When this is the case, partners can be supported to build readiness through capability-building, community-strengthening activities or, as a starting point, more partnered approaches.

Different supporting teams or organisations

All successful place-based approaches will be led by a collaborative governance group, with clear terms of reference that ensure representation from across the community.

All kinds of governance benefit from diversity—this is especially true when working in a place-based way. When establishing a governance group, conscious effort should be made to include a range of voices in a community, rather than replicating existing power structures or only engaging the ‘usual suspects’.

All governance groups should include Aboriginal leadership.

Place-based approaches also require a structure, team or organisation to support the governing group and coordinate the work (sometimes referred to as a ‘backbone’).

Different place-based initiatives will choose different homes for this coordinating function, depending on who is best-placed with the readiness, connections, drive and resources to take on the role.

Following are some examples of potential homes for supporting teams, and how government can support them.

| Government team |

| Involves - establishing a new or using an existing state government team or authority. |

|

Best suited to issues or opportunities where state government:

|

| Example Latrobe Valley Authority. |

This model is housed within the Victorian Government, and the types of resources it might require include:

|

|

Community organisation team |

Local government team | Coalition team |

|

|

|

|

Best suited to issues or opportunities where community:

|

Best suited to issues or opportunities where local government:

|

Best suited to issues or opportunities where:

|

|

Example The Centre for Multicultural Youth and the Wyndham Community and Education Centre are the auspice organisations for Community Support Groups. |

Example The local council coordinates and delivers the Flemington Works project. |

Example Tasmania’s Burnie Works initiative is supported by a distributive backbone support team with members from government, non-government and business sectors. |

These models are led by partners outside of the Victorian Government. Government can support them by providing:

|

Different methodologies, models and tools

The most effective place-based approaches involve a diverse group of stakeholders coming together to work towards shared outcomes.

Collaborative approaches support and guide people to achieve change, with an emphasis on agile and adaptive ways of working to support cycles of small-scale testing and learning.

When collaborating to achieve change, government partners contributing to place-based approaches can draw on a broad range of methodologies and tools—whether established or newly developed.

Identifying the most suitable methodology and tools depends on purpose, context and objectives. Place-based approaches may draw

primarily on one of them or use a mix to achieve agreed goals.

Because there are many ways to implement place-based approaches, these can be used to guide effort depending on the phase of work the place-based approach is in. Methodologies that offer a structure to guide the implementation through the different phases of collaborative place-based work include:

- Collective Impact Framework

- utilised for population-level change outcomes

- Smart Specialisation Strategy—

- utilised for regional development outcomes

- Asset-based community

- development—utilised for local community-level strengthening

A number of models and tools are available that can support ways of working and provide mechanisms to enable the place-based approaches to achieve agreed priorities include:

- Systems change

- Adaptive cycle

- Co-design and human-centred design

Policy designers can draw on these options as they work with local stakeholders to identify those that are best suited to the local context and desired level of change.

This will involve engagement with different groups and communities, based on the demographics of the local area, to understand their experience of place, and ensure activities will support their needs. It is critical that methodologies, models, tools and engagement approaches are tailored to meet the unique needs of diverse community members, including Aboriginal Victorians, people from culturally and linguistically diverse communities, people with disabilities, children and young people, older people and LGBTQI people.

Victoria’s Public Engagement Framework, which is being developed, can be used as a tool to promote inclusive engagement.

Different ways of sharing decision-making influence, control and accountability

Government could share decision-making, influence, control and accountability—it is important to consider not just how but why.

Community having some authority within the initiative is a defining feature of place-based approaches. Central to their success are shared objectives, accountability and partnership.

An awareness of the structures and systems that produce or reinforce power (including governmental power) is key to doing this work well. Power-mapping can be a useful tool to help you.

When and how will vary according to government’s appetite for risk and local partners’ capacity or readiness. It is important to note these might change throughout the life of the initiative.

Throughout an initiative, government needs to continually interrogate if we are sharing the right level of decision-making, influence, control and accountability and if we are sharing them in the right way, for example by asking:

- Are the people with the most knowledge and expertise supported to decide how to engage with an issue or opportunity?

- Are Aboriginal Victorians and communities being empowered consistent with the principles of self-determination and the Victorian Government Aboriginal Affairs Framework and the Self-Determination Reform Framework?

- Is partnered decision-making supporting stakeholders to progress towards an outcome?

"Collaboration…comes with uncertainty, and it requires decision-makers to share power and be open to sharing data, lessons and failures". Centre for Public Impact (2019). The Shared Power Principle: How governments are changing to achieve better outcomes.

Self-determination and place-based approachesThe Victorian Government is committed to advancing Aboriginal self determination through systemic and structural transformation. This commitment is articulated through the Victorian Aboriginal Affairs Framework 2018–2023 and the Self-Determination Reform Framework. The Victorian treaty process marks a new era of governing and policy making in the Victorian Government. It will require public servants to work in new, collaborative and innovative ways to support Aboriginal self determination to create fundamental change for Aboriginal Victorians Place-based approaches can be a key tool for the Victorian Public Service to enable self-determination as they support the transfer of power and resources to Aboriginal communities and organisations to pursue their economic, social and cultural priorities. With commitment from government to reform its systems and structures to support self-determination, place-based approaches can support Aboriginal communities and organisations to define and work towards priorities and outcomes that reflect community aspirations. Place-based approaches do not inherently empower Aboriginal Victorians. We must consciously incorporate principles of self-determination to ensure these approaches include Aboriginal Victorians and recognise their unique and enduring connection to place as the Traditional Owners of Victoria’s lands and waters. Place-based approaches should commit to inclusive engagement and include self-determination as a guiding principle, regardless of the outcome or model identified. |

"Change happens at the speed of trust...Working, trusting relationships at every level is key to these initiatives...Trust is built through principled action that demonstrates people do what they say and through people seeing outcomes." The Australian Centre for Social Innovation (2019). Place-based collective impact: Framework for Practice.

Implementing place-based approaches

Place-based approaches take time and patience—they do not follow a traditional program or policy cycle.

In practice, place-based approaches are cyclical journeys that move at the ‘speed of trust’

Place-based approaches differ from traditional program or policy development processes: they focus more on building readiness and creating shared outcomes that will enable collaborative implementation.

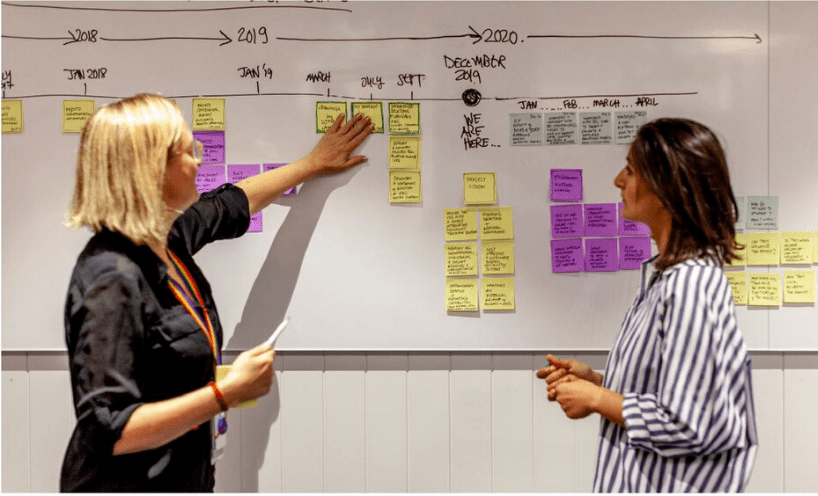

Table 1 outlines a typical process of how a place-based approach might play out. However, this process is often not linear. Initiatives may cycle back to earlier phases to build readiness and shape a shared vision as new barriers are discovered or new partners come on board.

Furthermore, because place-based approaches often start within community, government may later join the process. For example, government might become engaged when community has developed a shared vision for change and is starting to plan for the resources and skills they will need to make it happen.

This is especially true of enabling responses, and requires us as government to focus on supporting initiatives, rather than shaping them.

Table 1: Typical process for developing and implementing a place-based approach

| 1. Identify if a community would benefit from a place-based approach |

Use in-depth local knowledge to assess if a place-based approach would be an appropriate response to local opportunities or challenges. |

| 2. Assess readiness |

Assess if a community is ready to or is already self-mobilising around an opportunity or issue, and if government is able to meaningfully contribute. This considers if the required resources, leadership, connections and mindsets exist—or if they could be built. |

| 3. Develop a shared vision for change | All community members and organisations with an interest come together to identify the change they want to make in the community. This is articulated with clear outcomes, measures of progress and impact and a plan for making it happen. |

| 4. Implement together | Local partners work with government and other organisations, such as business and philanthropy, to resource and implement the plan. A local collaborative governance group oversees the implementation and has the ability to make changes. |

| 5. Embed a culture of learning and continual improvement | All partners embed a culture of learning to bring in new ideas and keep the initiative effective and relevant. Evaluation enables them to assess if work is progressing shared outcomes, learn from failures and consider how practice and policy changes can be embedded into their organisations over the long term. |

| 6. Celebrate and communicate success | Everyone should be supportive of each other and ensure achievements are recognised and celebrated. |

The cyclical nature of this process, and the fact that place-based approaches are often responding to complex or intersecting factors, means the timeframe in which you would expect to see impacts may also differ from a traditional program.

Figure 2: Place-based approaches often take some time to demonstrate impacts. Adapted from: Dart, J. 2018. Place-based Evaluation Framework: A national guide for evaluation of place-based approaches, report, Commissioned by the Queensland Government Department of Communities, Disability Services and Seniors (DCDSS) and the Australian Government Department of Social Services (DSS).

| Late years 5–9 | Local population impact Sustainable positive outcomes are being observed in the whole of the community or the targeted cohorts (rather than specific users), showing how people’s lives or places have changed and inspiring others to become involved in the approach |

| Middle years 3–5 | Systemic changes in the community

|

| Initial years 1–3 | Enablers for change Things are being put in place (e.g. community priorities to direct investment; capacity building; transparent governance; an integrated learning culture) to enable an approach to create systemic change. |

| Set-up phase | Foundations The readiness of people to begin the change journey is being built. Because every initiative will start from a different point and require different foundations, the length of this phase will be different for each place-based approach but will take at least one to two years. |

|

WHAT DOES THIS MEAN FOR MEASURING SUCCESS? Place-based approaches are often regarded as challenging to evaluate because they deal with complex issues over a longer-term period and with a broad range of stakeholders. Because place-based approaches encourage working across organisational boundaries and ensuring the locus of control is with the people best-placed to lead, they can also have a ‘popcorn’ effect: a great idea might ‘pop up’ because of the time and space a place-based approach has created (e.g. collaborative governance groups, facilitated exploration of shared outcomes), but it might end up being led by another group or initiative and, so, would not be directly attributable in a traditional evaluation context. However, it is crucial to thoroughly evaluate place-based approaches—to support a culture of continual learning and to ensure effort is translating into systemic change for people and communities. Evaluations should be designed to measure the appropriate type of impact over the lifetime of an initiative (as outlined in Figure 2). It is important to define the anticipated changes in community outcomes as well as the measures and datasets that will allow progress to be tracked. For example, in the initial years, measures of success might focus more on enabling conditions and processes—looking at whether strong governance is in place, partners are working collaboratively together, and flexible and innovative mindsets are being embedded. As the project develops, it is important to assess if these ways of working are translating into outcomes for individuals or specific cohorts. Over the longer-term, evaluation can show if an approach is embedding systemic change that improves outcomes for target cohorts or the whole community. Because place-based approaches actively engage the community, evaluations must also involve local partners in the design, collection of data and development of recommendations. To value and capture community voice, evaluations are also inclusive of different types of evidence, including cultural and local knowledge. |

Updated