In Victoria, public entities may be established using several legal forms.

The ‘legal form’ of a public entity refers to:

- the way it is created — whether this be through a legislative or a non-legislative process:

- a statutory authority established by or under legislation

- a non-statutory advisory body established by a minister or Governor in Council

- a corporation established under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Corporations Act)

- its status as an incorporated or unincorporated body.

There is no simple system for matching functions and legal forms. The variety of legal forms gives rise to a range of legal terms and descriptions, some of which overlap. For example, state owned enterprises (SOEs) are a form of statutory authority.

The focus of this information is on providing guidance on establishing the different forms. The guidance describes a generic version of each legal form but these can be modified and tailored to suit the circumstances of a given public entity (although this does carry some risks—see 'Statutory Authorities' below). This information may also be useful when undertaking a review of an existing public entity.

There is also flexibility to determine the specific governance arrangements that will apply to a particular public entity. See public entity governance arrangements for more detail.

Incorporated or unincorporated

When selecting a legal form, the first step is to select between an incorporated or unincorporated body.

Incorporation provides a separate legal identity for the public entity, which protects the liability of members of the public entity to a greater extent than an unincorporated body. Liability means that you are legally responsible for something. In an unincorporated body members may be liable for the actions of other members. to a greater extent than an incorporated body.

Incorporation is necessary if the public entity is to:

- employ staff

- provide services to non-government parties

- own or lease property or other assets

- receive funding from direct budget allocation and/or other sources

- enter into contracts

- perform functions which expose it to potential legal challenge

- take legal action against others.

Incorporated public entities are used for a wide range of functions and have several legal forms, including:

- statutory authorities

- SOEs

- Corporations Act companies

- incorporated associations

Unincorporated bodies can be used for activities such as mediation, facilitation, and dispute resolution. Unincorporated bodies also are often an appropriate form for non-statutory advisory bodies.

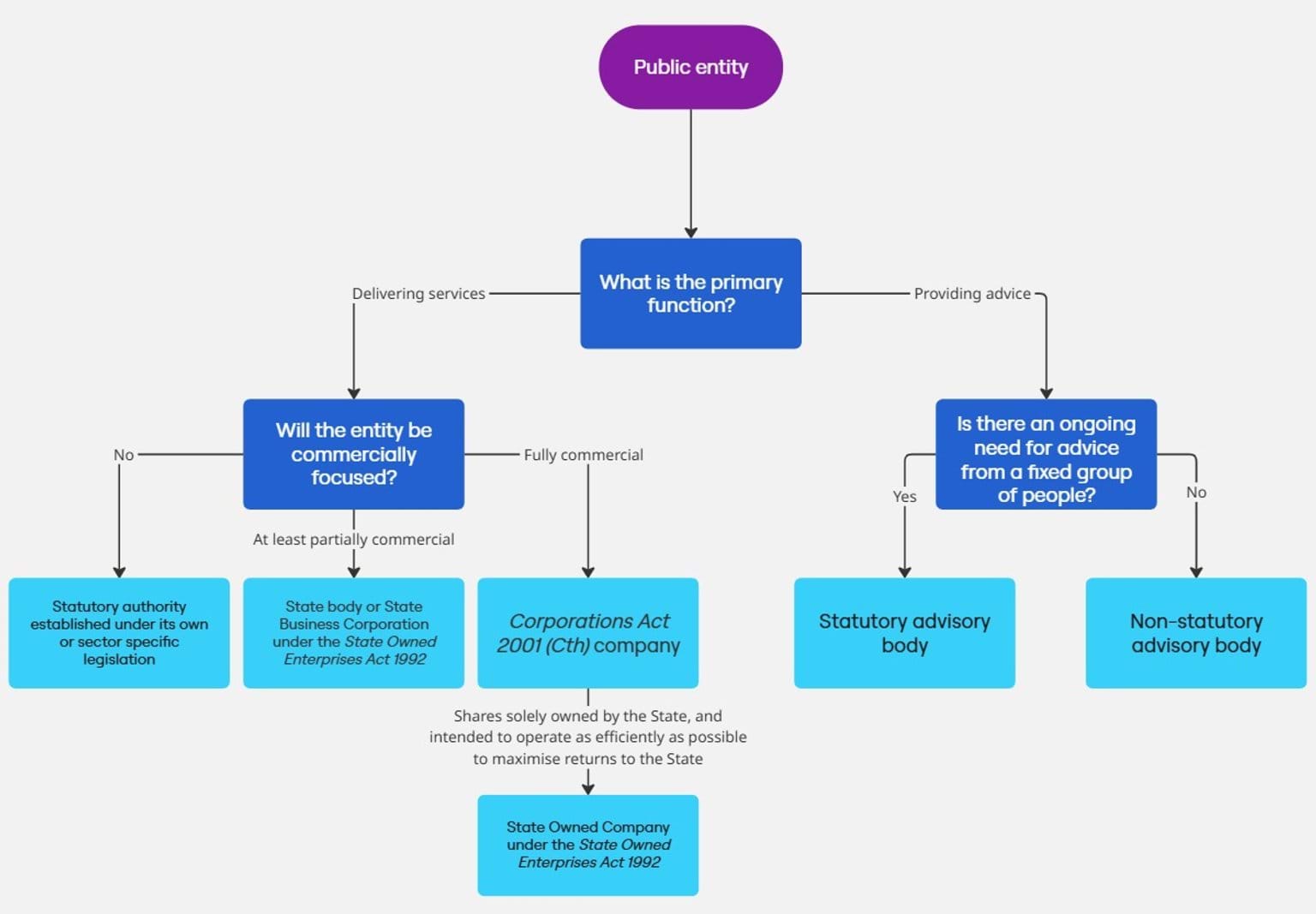

Consider the functions

When exploring the possible suitable legal forms of a public entity, you should consider what functions the entity will undertake. As previously discussed, public entities often perform multiple or hybrid functions.

Use the decision tree below to help find possible legal form matches.

Statutory authority

A statutory authority describes a public entity that is established by Victorian legislation.

A statutory authority may be appropriate when functions require:

- operational independence from ministerial influence,

- legal independence from the Crown.

In general, a statutory authority is the most appropriate legal form for entities that are perform specific functions that cannot be undertaken by a public service body and are broader than the provision of advice. Refer to the Advisory bodies resource <link> for more information for public entities undertaking advisory functions.

There are no predetermined legal rules for the establishment of a statutory authority, giving significant flexibility to tailor the governance arrangements to the specific entity. However, as far as possible, new statutory authorities should attempt to establish governance arrangements that are consistent with other similar entities, as novel governance arrangements can result in non-compliance.

Public entity governance arrangements provides greater detail on:

- appropriate level and forms of ministerial direction and control

- governance structures

- employment arrangements

- the application of whole of Government legislation

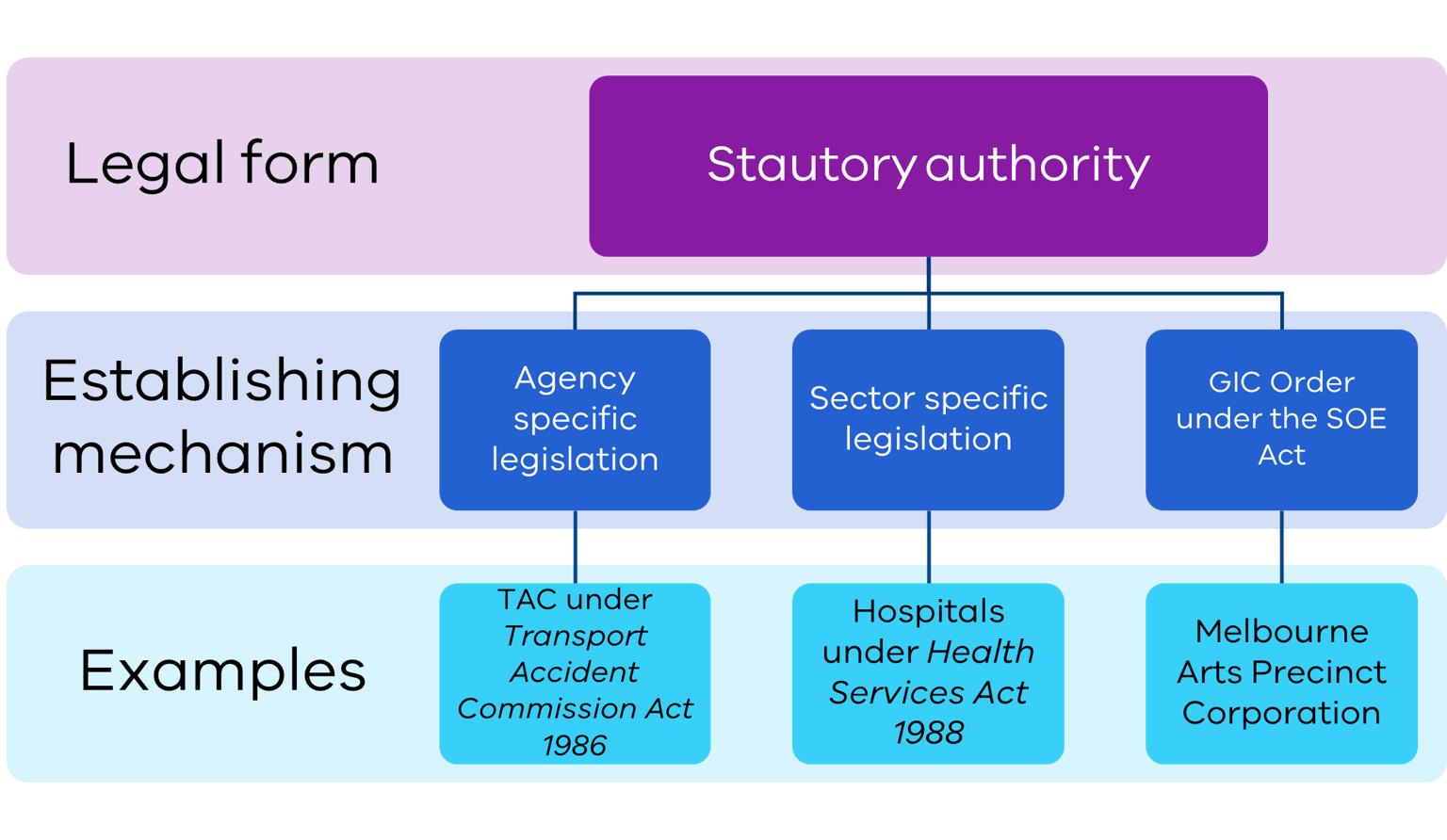

Establishing mechanisms

There are three ways a statutory authority can be established:

- agency establishing legislation (‘own legislation’)

- sector-specific enabling legislation (‘legislative framework’)

- the SOE Act.

The different legislative mechanisms to establish a statutory authority are compared in the table below.

| Agency-specific establishing legislation | Sector-specific enabling legislation | SOE Act | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Considerations | Allows for the provision of clear direction on the objectives, functions, purpose, and operation of the statutory authority, for example through the establishing legislation itself. This also provides a public record of the government’s purpose in establishing the entity. Significant lead times may be required to establish the entity and it can be a lengthy and highly visible process to amend or repeal the legislation. | Provides a legislative framework under which multiple statutory entities with similar functions and activities can be established. The initial development and establishment of legislation can have a long lead time (as is the case for agency-specific establishing legislation). Once legislation is in place, the establishment of new public entities can be achieved relatively quickly. These entities are also easier to abolish. | The SOE Act enables public entities to be established by the Governor in Council, without new legislation being passed by Parliament. |

| When to use | To establish ‘stand-alone’ bodies with unique functions, objectives and powers. | May be more appropriate where there are multiple entities with similar purpose and functions. | May be appropriate for those delivering services in a commercial manner. |

| Examples | Transport Accident Commission established by the Transport Accident Act 1986 The Victorian Managed Insurance Authority established by the Victorian Managed Insurance Authority Act 1996 | Community health centres and hospitals established under the Heath Services Act 1988. | Melbourne Arts Precinct Corporation established by the SOE Act. |

State owned enterprises

SOEs are a kind of statutory authority established under the SOE Act.

SOEs are most appropriate where the primary function of the entity is to deliver services in a commercial manner. Services may include direct services to the public or stewardship, integrity, regulatory or other services for government.

Any financial reporting obligations in the SOE Act do not supersede obligations under the FMA. Financial reporting obligations under both Acts continue to apply.

The SOE Act defines four types of SOEs, each with different objectives and functions. The key features of each type are set out below.

Establishing mechanisms

SOEs are created by an Order of the Governor in Council, following Cabinet approval. This means that SOEs can be established quickly. However, they will not benefit from the Parliamentary scrutiny that is required to establish statutory authorities under unique legislation. Orders establishing SOEs are published in the Victorian Government Gazette.

Comparison of SOEs

The below table summarises the information outlined above about the key differences between the different types of SOEs.

| State body | State Business Corporation | State Owned Company | |

|---|---|---|---|

| How is the entity established? | By Order of the GIC, published in the Government Gazette setting out the entity details listed at s 14(2) of the SOE Act. | By Order of the GIC, published in the Government Gazette, a state body or statutory corporation can be declared an SBC. | By Order of the GIC, published in the Government Gazette, a company may be declared an SOC, if the shares in the company are held only by the State* as set out in s 66(1) of the SOE Act. For the meaning of the “State” please refer to the SOE Act. |

| Rules and procedures for governance | Set out in the GIC Order. May be minimal, for example, a multi-member board is not required. | Set out at Part 3 of the SOE Act. Must have a board of between 4 and 9 directors. May be supplemented by specific legislation for an entity. | Set out in the Corporations Act, and a Memorandum of Association which must at least include the provisions set out at Schedule 1 of the SOE Act. |

| Appointments and duties of directors | GIC Order may include provision for the appointment of directors by the GIC. | An SBC must have between 4 and 9 directors, appointed by the GIC (ss 23, 25) on terms and conditions determined by the minister and Treasurer (s 26). Director’s duties are set out in the SOE Act. The GIC may remove a director (s 30). Minister determines terms and conditions of CEO or deputy CEO on recommendation of the SBC board (s 40). | Directors are subject to a range of legal duties including their professional judgment, conflicts of interest and reporting requirements. The core duties contained in the Corporations Act largely codify the common law on directors’ duties. |

| Public accountability / reporting | None under the SOE Act, but standard accountability and reporting obligations for public entities.

| None under the SOE Act, but standard accountability and reporting obligations for public entities. | The Treasurer must ensure an SOC’s Memorandum of Association, and Corporations Act directors’, auditor’s and financial reporting is tabled before each House of Parliament. |

| Government accountability / reporting | No reporting is required under the SOE Act, though reporting requirements may be drafted in the GIC Order. Additional requirements may be incorporated into the GIC Order. | The board is obliged to notify the minister and Treasurer of “significant affecting events” (s 54). An SBC must provide at least half-yearly reports on its operation to the minister and Treasurer (s 55). The minister can require any information to be provided in the report. The Treasurer may at any time request a report from the board (s 53). | The Treasurer may require an SOC to prepare and deliver financial reports, business plans, annual reports or other information. |

| Government control or direction | After consultation between the Treasurer and the relevant minister, either may, from time to time give directions to the board by written notice (s 16C of the SOE Act). | Limited to input into and influence of an SBC’s mandatory corporate plan and statement of corporate intent (ss 41-43). The minister, with the Treasurer’s approval, may direct the board to perform or cease to perform non-commercial functions (s 45). An SBC action or decision is not legally invalid merely because it does not comply with its corporate plan or the minister’s directions. | The State or Treasurer as shareholder may have the ability to influence the SOC, under the Corporations Act. An SOC is the most independent form of SOE from government. |

| Functions | Functions are drafted in the GIC Order. May be broad or specific, or more or less “commercial”. | Functions may be drafted in the GIC Order, or by legislation. The principal objective of each SBC is to perform its functions for the public benefit by— (a) operating its business or pursuing its undertaking as efficiently as possible consistent with prudent commercial practice; and (b) maximising its contribution to the economy and well being of the State. | Functions may be drafted in a constitution, or by legislation. The principal objective of each SOC is to perform its functions for the public benefit by— (a) operating its business or pursuing its undertaking as efficiently as possible consistent with prudent commercial practice; and (b) maximising its contribution to the economy and well being of the State. |

| Nature and source of powers | Powers must be set out in the GIC Order (s 14(2)(b)). May have such powers under the Borrowing and Investment Powers Act 1987 (Vic) as are conferred on it by GIC Order (s 14A). This also requires an update to the BIP Act’s regulations.

| Under the SOE Act, an SBC can do all things necessary or convenient to be done for, or in connection with, or incidental to, the performance of its functions (s 20). Powers and functions apply within and outside Victoria and Australia (s 21). | Powers established by virtue of the SOCs incorporation and legal status (under statute and at common law). No power to bind State or render State liable for any debts, liabilities or obligations of the SOC (s 70). |

| How is the entity dissolved? | By GIC Order on the recommendation of the Treasurer and relevant minister. | By GIC Order on the recommendation of the Treasurer and relevant minister. The underlying entity would need to be separately abolished once it ceases to be an SBC. | By GIC Order on the recommendation of the Treasurer and relevant minister, and the process outlined in Part 5.5. of the Corporations Act |

Advisory bodies

Departments generally are responsible for providing policy advice. However, in some cases, ministers may choose to establish external advisory bodies to provide specialised advice that cannot be provided by the department.

An advisory body should only be formally established as a non-departmental entity if it is intended to provide advice to a minister, and there is a clear ongoing need for independent advice from a fixed group of members.

A minister can also consult with stakeholders without establishing an advisory body. These less formal options like roundtables should always be considered before deciding to establish a new entity.

If an advisory body is established as a non-departmental entity to provide advice to a minister, there are two legal forms which may be suitable. This section will outline the key differences and considerations between statutory and non-statutory advisory bodies.

Other options where a department or public entity wishes to receive advice

Non-departmental entities are generally established to provide advice to ministers, not departments or other non-departmental entities.

In some cases, departments may wish to receive expert external advice. This advice does not need to be delivered through an entity that is formally established by an instrument and, in practice, can be achieved by engaging relevant experts as contractors. You should refer to the Administrative Guidelines on Engaging Labour Hire in the Victorian Public Service before engaging any contractors.

If the governing body of a public entity requires advice, they also likely do not need to establish a new entity. Many public entities are given the power to engage contractors under legislation, which may be appropriate. Alternatively, public entities can establish sub-committees under section 83 of the Public Administration Act 2004 (PAA). The membership of these sub-committees is not limited to the members of the entity’s governing body, so this can be a way to form advisory committees. These sub-committees do not count as separate non-departmental entities, and they can be created and abolished at the board’s will.

Other legal forms

In addition to statutory authorities and non-statutory advisory bodies, there are other possible legal forms for public entities. These are only appropriate in limited circumstances. and include companies established under the Corporations Act and incorporated associations.

Corporations Act companies

A Corporations Act company should only be used where an entity is to perform functions with a highly commercial focus. This is uncommon in the public sector.

If you are considering establishing a Corporations Act company, you should seek advice from:

- the Department of Treasury and Finance

- the Department of Premier and Cabinet’s Governance Branch.

Companies can be established and incorporated under the Corporations Act. Corporations Act companies in the public sector can be set up as companies limited by shares or companies limited by guarantee. These have different approaches to ownership and liability:

Unlike a State Owned Company, Corporations Act companies are not required to operate as efficiently as possible to maximise their contribution to the economy.

As with SOEs, the reporting obligations under the Corporations Act do not displace requirements under the FMA. Corporations Act companies must comply with both sets of obligations.

Considerations for Corporations Act companies

There are limitations on how much the government can direct and control a Corporations Act company. This is because directors are required to act in the best interests of the company itself, which may not always be consistent with government policy directions.

Following a decision to establish a Corporations Act company, the government’s control over these entities is generally limited to decisions about the composition of the board. Employees and board members remain bound by the public sector provisions of the PAA (e.g., values, code of conduct).

Reporting and other obligations for Corporations Act companies can be substantial and potentially onerous. Given the complications associated with the use of the Corporations Act as a legal form, there are relatively few examples in the public sector.

Incorporated associations

Incorporated associations are entities incorporated under the Associations Incorporation Reform Act 2012, Incorporated associations are non-profit organisations, meaning that they can trade but profits can’t be distributed to members.

This legal form is designed to support small scale community/not-for-profit organisations with little or no capital base, such as a sporting club, or a recreational or special interest group. It offers an alternative to the company form in terms of granting the benefits of incorporation, including:

- being able to enter into contacts

- the entity legally continuing regardless of changes to membership

- protecting individual members of the association against personal liability.

The Associations Act applies differential financial reporting and auditing requirements to incorporated associations depending primarily on their annual revenue, with requirements for review and auditing of financial records escalating as annual revenue increases.

However, governance and accountability standards for the boards and directors of these entities are generally less rigorous than most other public entity forms. Therefore, establishing an incorporated association is generally not appropriate for a new public entity, where performing a public function and exercising public authority require high standards of governance and accountability.

Updated