The previous section of the guidance outlined a framework for matching public entity functions and legal forms. The next stage in designing a public entity involves specifying the governance arrangements to suit the entity’s needs.

The legal framework establishing an entity (such as the establishing legislation, Order-in-Council instrument, or constituting terms of reference) should set out key governance arrangements.

You should think about the advantages and disadvantages of the different governance options.

Guiding questions

- What level of interaction between the entity, the relevant minister and the department (as adviser to the minister) is desirable?

- What specific powers does the minister require?

- How will the board be appointed and what skills are required on the board?

- What are the processes, and under what circumstances could a board member be removed?

- What management structure suits the public entity’s functions?

- How will staff be employed?

- What funding sources and financial delegation arrangements are appropriate?

- What whole of government legislation will apply and how will this be achieved?

- Which government policies will apply to the entity?

- Which code of conduct will apply to the employees and officers (including board members) of the entity being established?

It may help you to review the governance arrangements of existing public entities to understand how the various options work.

In limited circumstances, a public entity may be headed by an individual rather than a board.

Relationship between the entity, minister and department

What level of interaction between the entity, the relevant minister and the department (as adviser to the minister) is desirable?

Public entities have a high degree of autonomy in their operations. However, they are subject to varying levels of ministerial direction regarding compliance with government policies and strategies. On a day-to-day basis, there is a separation between the public entity and ministerial direction.

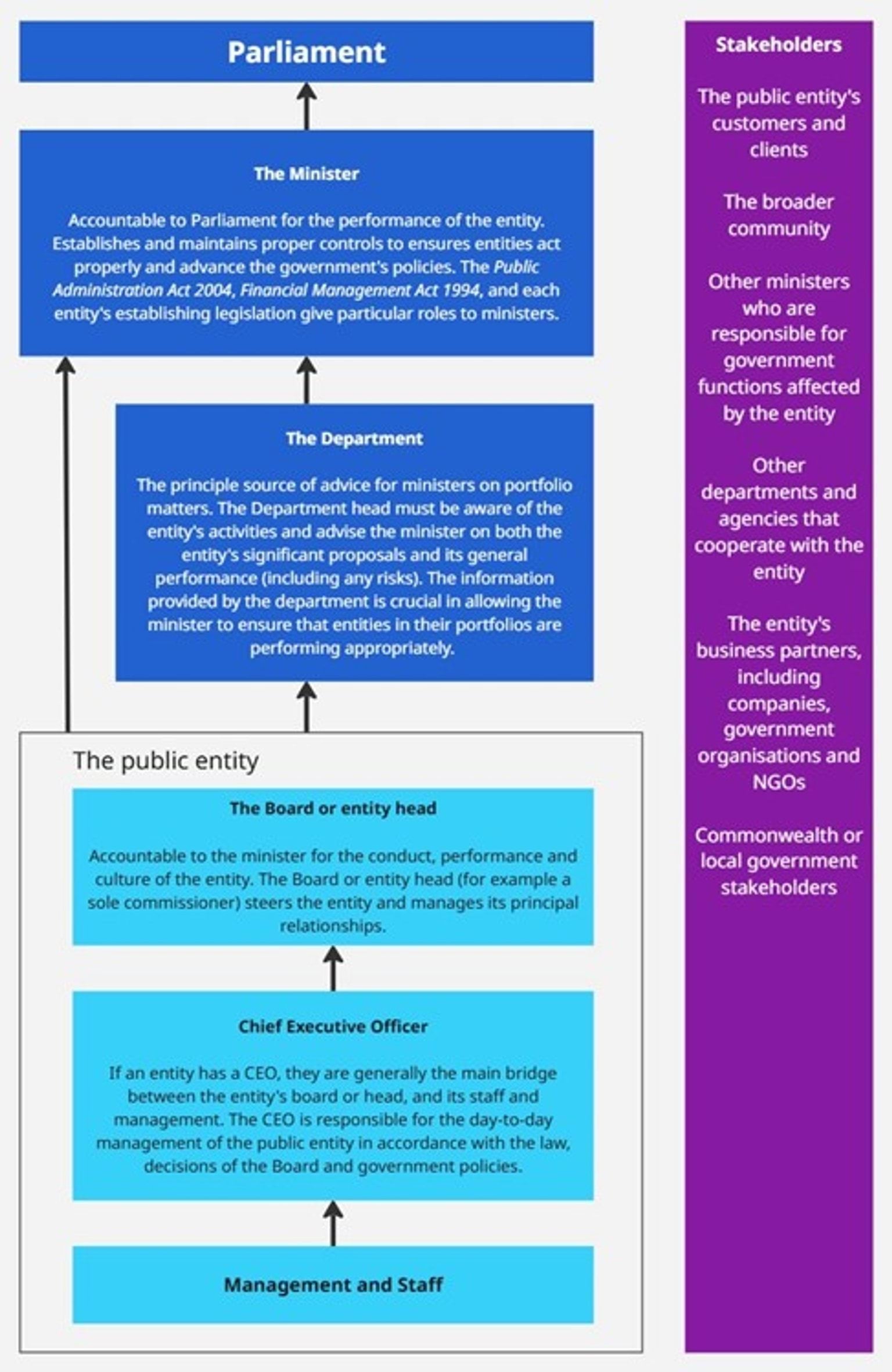

Under Victoria’s Westminster system of government, ministers are accountable to Parliament and the Victorian community for the performance of their portfolio public entities, consistent with the principle of responsible government.

The nature of the interaction between the entity and the minister is set out in the legislation or other instrument that establishes the entity (such as a Governor in Council establishing order). The powers of the minister to direct the entity should be clearly defined by these instruments.

Determining specific ministerial powers, the degree of independence of the entity and its relationship with the portfolio department is undertaken on a case-by-case basis and depends on the functions and objectives of the entity.

General guidance on the roles and responsibilities of each stakeholder is provided in the following sections.

Memorandum of Understanding

A memorandum of understanding (MOU) should be formed between a public entity and portfolio department to formalise governance arrangements and clarify expectations. MOUs are voluntary statements of intent that set out the commitments of each party. Factors commonly covered by MOUs include establishing communication and briefing processes and agreeing on the corporate costs that will be charged to the public entity.

Sometimes an MOU can also be formed between two or more public entities, particularly where functions may overlap or there is a need for information to be shared between entities.

Ministerial powers

What specific powers does the minister require?

The degree of influence a minister has over any particular entity, and its degree of independence should be informed by the desired functions and/or policy objectives of the proposed entity.

The below section discusses common functions in the Victorian public sector and possible levels of ministerial control to support the body to achieve its functions.

The table below summarises the information provided above about governance arrangements for public entities performing different functions and the impact of the level of control and direction provided by the minister.

| Public entity function | Functional implications | Legal form options | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

Service delivery Directly undertake | High degree of ministerial control over strategic directions and policy. Limited ministerial control over operations due to specialist/technical nature. | Statutory authority, governed by a board or individual appointment. | Melbourne Health (Royal Melbourne Hospital) Roads Corporation |

Stewardship Manage public assets | High degree of ministerial control over strategic directions and policy. Limited ministerial control over operations due to low risk nature. | Statutory authority governed by a board. | Shrine of Remembrance Trust Crown land committees of management. |

Integrity Scrutinise the actions and decisions of public officials | Little or no ministerial control over operational decision making, strategy and direction due to requirement for impartiality. | Statutory authority, generally governed by an individual appointment. | Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission. |

Regulatory Administer regulation | In some cases there can be some degree of ministerial control over strategic directions and policy. Little or no ministerial control over day to day and operational decision making. | Statutory authority, governed by a board or individual appointment. | Essential Services Commission. |

Quasi-Judicial Exercise quasi-judicial powers. | No ministerial control over strategy, operations, or decision making due to requirement for impartiality. | Statutory authority, governed by a board or individual appointment. | Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (VCAT). |

| Advisory Provide advice directly to a Minister or ongoing research | Ministers determine scope of activities but has no control over advice provided | Statutory authority, governed by a board or individual appointment.

Non statutory advisory body | Infrastructure Victoria |

Ministerial Statement of Expectations

A Ministerial Statement of Expectations is a formal and public statement that establishes the expectations the responsible minister has for the public entity. You should consider whether the responsible minister should issue a public entity with a Statement of Expectations. These statements should be mindful of the appropriate relationship between the responsible minister and the entity, ensuring that they do not compromise the independence of entities established at an arms-length from government.

The minister’s Statement of Expectations may outline expectations for a public entity with consideration to:

- a government policy or policies

- the performance, behaviour or conduct of the entity.

Entities that perform regulatory functions may be subject to DTF’s Statement of Expectations Framework for Regulators. More information can be found by accessing Statement of Expectations for Regulators.

Board structure

Is a governing board the best option or should the entity be headed by a single person?

Governance of public entities can be configured as multi member or single member arrangements

A multi-member board of governance is generally the default position when establishing a new public entity and most Victorian public entities operate this way. The Board is charged with making decisions about the direction and operations of the entity and reports to the relevant minister. Board chairs sometimes will have additional powers or responsibilities.

In some cases, individual appointments, such as commissioners, can form a corporation sole, which is where a single person is a legal entity with the status of a corporation or office. This form is more appropriate when the appointee will need to be actively involved in exercising the entity’s functions, while boards are more suited to governance and strategy. If you are considering this option, you should discuss this with Governance Branch, DPC early in the policy process.

If the entity is being established under existing enabling legislation, it may mandate certain decision-making structures. For example, the State Owned Enterprises Act 1992 (SOE Act) requires that state business corporations operate with a board of between four and nine directors.

A multi-member board is should always be the preferred design where:

- the public entity’s functions are sufficiently complex to require a diversity of skills and experience that may not be available if a single commissioner were appointed

- there is a range of functions for the multiple board members to oversee.

A board should include members with a range of different skills, including sufficient finance skills to acquit the board’s responsibilities for the entity’s financial management. A single appointment would need to source any additional skills required from employees (who don’t participate in decision making) or from external sources.

If a board structure is selected, you should consider the number and nature of appointments to the board. To serve their purpose and be effective, boards need to be established appropriately and granted sufficient and clear powers to act as a board. As boards are governing bodies, they should have a skill set that reflects the need for governance expertise across a range of areas. They should not be representative bodies (i.e. composed of representatives from relevant industries).

The number of board members should be related to the anticipated size of the governance task involved. Larger and more complex public entities may require larger boards, while smaller public entities with limited functions and budgets may not require as many board members if the mix of necessary skills can be covered, including sufficient members to form an Audit and Risk Committee. In general, there is a trend towards smaller boards. Even in the case of more complex public entities, you should consider carefully whether more than eight members are genuinely required, noting that large boards can be difficult to manage.

How will the board of individual appointee be appointed?

You will also need to consider how board members or the individual appointee will be appointed.

Appointments may be made by the relevant minister or by the Governor in Council on the recommendation of the minister.

In some circumstances, existing general legislation mandates certain appointment processes.

Guidelines

The Appointment and Remuneration Guidelines outline Victoria’s standard processes for appointing people to government boards and offices. The Appointment and Remuneration Guidelines also provide for the classification of non-departmental entities to inform the remuneration of board members.

Board appointment, remuneration and diversity guidance ensure that appointments to Victorian government entities reflect the diversity of the Victorian community. The Diversity on Victorian Board Guidelines provide advice to support diversity on boards.

Which code of conduct should apply to the board members/ individual appointee?

The Victorian Public Sector Commission issues binding codes of conduct.

Directors of Victorian public entities and statutory office holders are bound by the Code of conduct for directors of Victorian public entities.

Resources to support Victorian public sector board directors and chairs are available on the Boards Victoria website.

Employment arrangements

Key principles

The following key principles should guide consideration of the employment arrangements for a public entity.

Does the entity require staff?

Advisory bodies and small entities usually do not require dedicated staff and can receive relevant secretariat support from the department.

Most other public entities will require staff. Allowing entities to directly employ their own staff is the most common arrangement, although in some cases legislation will specify that the department must make staff available to support an entity instead.

Even where staff are employed directly by the entity, it is worth considering whether some things can be shared with the department of other entities to create efficiencies and reduce organisational costs, such as:

- Office accommodation

- administrative systems such as:

- IT systems

- finance and accounting

- legal services

- payroll and human resources functions.

You should consider these options as part of the entity design process to reduce future costs associated with migrating functions after the public entity is established.

How will staff be employed

For public entities to directly employ their own staff, the public entity needs to be provided with employment powers.

The available options depend on the legal form of the entity:

- Statutory authority – power is generally specified in the entity’s establishing mechanism, such as the establishing legislation or establishing Order in Council).

- State owned enterprises excluding State Owned Companies – power must be given in the establishing Order, or through a declaration as a ‘declared authority’ under section 104 of the Public Administration Act 2004 (PAA).

- Corporations Act company (including State Owned Companies) – employment powers are inherently granted through registration with ASIC.

Generally, you should include the employment power in the establishing mechanism so that it is clear how the public entity is able to employ staff.

In exceptional circumstances, public entities may be supported by public service staff employed through a delegated power of employment from the portfolio Department Head. Under this model, the Department Head must sign an instrument delegating their employment powers under Part 3 of the PAA to the Head of the relevant entity for the purposes of employing staff required to execute the entity’s functions. This may be appropriate for very small entities, or as a transitional provision for entities that need to be established urgently. It is a common arrangement for inquiries such as Royal Commissions or Boards of Inquiry. However, this approach creates additional administrative burdens and risks, including potential confusion about reporting lines. Therefore, it is usually not recommended, particularly on a medium or long-term basis.

Who will have the power to employ?

You need to consider who holds the employment power in a public entity.

Options include:

- the board as a collective

- the chair of the board

- the CEO.

Employment powers place significant responsibilities on the person/s who hold the power. This includes obligations to ensure compliance with the relevant:

- Commonwealth and Victorian employment legislation (e.g. legislation covering employment conditions)

- industrial agreements

- organisational policies

- government policies.

In some cases, employers can be personally held liable for outcomes, such as obligations for occupational health and safety.

Case study – industrial manslaughter

In 2024, LH Holding Management Pty Ltd became the first company to be convicted under Victoria’s industrial manslaughter laws. A worker was crushed by an overloaded forklift. The company plead guilty to the charges that it had failed to take reasonably practicable steps to ensure that the forklift was operated safely.

The company was issued a $1.3 million fine. Its sole director was also found to be personally liable due to his failure to discharge his duties to ensure a safe workplace. He was sentenced to community corrections order for two years. Both the director and the company were ordered to jointly pay $120,000 in restitution to the family of the deceased worker.

In addition to these responsibilities, public sector employers are likely to be held accountable for the actions of their employees by integrity bodies such as the Victorian Ombudsman, the Auditor-General and the Independent Broad-based Anti-Corruption Commission.

Preferred employment model

For entities governed by a board, the preferred model is that the board (as a collective) holds the power to employ the CEO and all other staff. In some instances (for example, when a public service body head needs to be declared), the employment power is held by the board chairperson instead of the board as a collective. The board chairperson should then formally delegate the power to employ all other staff to the CEO.

The power to delegate employment powers should be included in the legislation. The CEO should consider whether to delegate these powers to others, such as executive officers and others below CEO level. This will generally require board approval. These powers generally need to delegated by instrument. You should consult with your legal area about what these instruments need to involve.

Providing employment powers directly to the CEO is generally not recommended. This may dilute or confuse accountability of the CEO to the board for employment decisions.

When a board delegates employment powers to the CEO it ensures that the board has oversight of this key area of the entity’s operations and the CEO. This is appropriate as the board is responsible for governance and the CEO is responsible for day-to-day operational and management decisions. This model is also used in the private sector.

Boards should be clear that when they delegate employment powers they remain accountable for employment matters. The CEO is responsible for controlling employment decisions only. The board remains accountable for the actions of the delegate and needs to take appropriate steps to ensure that the delegate acts appropriately.

Appointment of the public sector body Head

In general, the CEO is appointed by the board, in consultation with the relevant minister. For a statutory authority, the terms of appointment are prescribed in the body’s establishing legislation.

For a state business corporation, section 40 of the SOE Act prescribes that the CEO and/or deputy CEO are appointed by the minister on the recommendation of the board. However, for other state owned enterprises there is no specified approval process to appoint CEOs outlined in the Act.

In some cases, CEOs (or other second level positions) are appointed by ministers or the Governor in Council, rather than the board. Generally, this model should not be used as it carries particular risks. The risks are demonstrated in the case study below.

Case study – Governor in Council

The board of a public entity has the power to employ staff. The CEO of the entity is appointed by Governor in Council. Recently, a new CEO was appointed by Governor in Council. Initially, the new CEO and the board developed a positive working relationship. However, in recent months, the relationship has deteriorated and the board is concerned that the CEO is not implementing its vision for the entity. In discussions between the chair of the board and the CEO, it is clear that the CEO does not see themself as accountable to the board. The CEO thinks they are accountable directly to government because they were appointed by government. The board is accountable for the actions of the CEO but the CEO is not following its directions.

How to classify Head position

To classify a public entity Head use the Public entity executive classification framework.

The VPSC maintains a handbook on public entity executive employment.

Questions about executive employment policy, should be sent to publicsectorworkforce@dpc.vic.gov.au.

Questions about seeking the Tribunal’s advice on proposals to pay above the remuneration band should be sent to enquiries@remunerationtribunal.vic.gov.au.

What type of staff will be employed?

Public entities can either be given powers to employ their own public service staff under Part 3 of the PAA or employ their own staff under separate enterprise agreements (which in this section will be referred to as ‘public sector staff’).

All public service and sector staff are bound by the majority of the PAA (Part 3 only applies to public service staff). This means that similar rights and obligations are conferred on all staff.

Most public entities employ public sector staff. This allows them to maintain a degree of independence from the government, and to tailor employment conditions to their operational needs, through the use of entity or sector-specific industrial agreements.

The proposed functions of the public entity will also determine what type of staff will be most often appropriate. The table below provides a summary of these most common arrangements. More detail about what these different arrangements involve is provided below.

| Function | Employment powers | Staff |

|---|---|---|

| Service delivery | Powers to be specified in establishing legislation. | Own staff, generally not public servants. |

| Stewardship | Powers to be specified in establishing legislation. | May require staff (depending on functions), generally not public servants. May be volunteers. |

| Regulatory | Powers to be specified in establishing legislation. | Department’s or own staff, who may be public servants employed directly by the public entity Head |

| Quasi judicial | Not usually required. | Departmental staff who are public servants. |

| Integrity | Powers to be specified in establishing legislation. | Department’s or own staff, who may be public servants employed directly by the public entity Head |

| Advisory | Not usually required. | Do not usually require staff. Staff provided by relevant departments. |

Employing public sector staff

Industrial Relations Victoria provides guidance for the public sector on industrial relations matters.

Further information is available on the Industrial Relations Victoria website.

Employing public servants

Public entities can employ staff as public servants. This arrangement is common when government needs to transfer existing public servants to the entity and wants to preserve their existing employment entitlements and conditions. Some agencies also choose this arrangement as their staff are clearly fulfilling functions that are similar to those of a public servant (for example integrity agencies). Some of these agencies are also declared to be special bodies to reinforce that their staff are not subject to ministerial direction.

However, there are some complexities to this arrangement, and the decision should be carefully considered in light of legal and industrial relations advice. You should also consult with DTF about any implications this decision will have under the Financial Management Act 1994 (FMA).

If required, there are several options for a public entity to employ public servants. These options are detailed in the below table.

Employment of public servants should generally be achieved through section 16(1) of the PAA, to ensure that all elements of the Act relevant to the employment of public servants, and any future amendments, are applied. Note that using this option means that the entity is automatically treated as a department under the FMA and therefore it is required to comply with the same standards of financial management as major departments. Using this option also ensures clarity about the status of the entity as part of the public service. DPC’s Governance Branch can be contacted if you wish to discuss this further.

Some public entities have employed a mix of public sector, public service and (in a small number of cases) non-government staff. This option is not recommended on a medium or long-term basis as it creates challenges for entities in ensuring consistent employment conditions and career opportunities for staff and creating a unified culture. It is only potentially appropriate where employers have two clearly distinct cohorts of staff (for example, if an entity employs a large policy team, but also needs clinical staff).

The below table outlines the options to employ public servants in public entities

| Options | Implications | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Preferred options | ||

Amend s. 16 of PAA Amend s. 16(1) of the PAA to declare a particular officeholder a ‘person with the functions of a public service body Head’ for the purposes of the PAA |

|

Refer to s. 16 of the PAA |

Order in Council declaration Obtain Order in Council under s. 16(3) of the PAA to declare a particular office holder a ‘person with the functions of a public service body Head’ for the purposes of the PAA |

|

Refer to Orders made under s. 16 of the PAA |

| Other available options | ||

Establishing Act Include provisions within the entity’s establishing act to provide a particular office holder with the powers to employ public service staff |

|

|

Declared authority Obtain an Order in Council to declare an entity to be a ‘declared authority’ for the purposes of the PAA Further information: Declared authorities <link> |

|

|

Secretary delegation Secretary of portfolio department provides public service staff by delegation NB: This option is not recommended and should only be used in exceptional circumstances, or for a limited time |

|

|

Employing executives

As with non-executive staff, public sector bodies may employ their executive officers with reference to public service or public sector / entity arrangements. Different employment and remuneration frameworks apply for these two cohorts.

In relation to public service executives, Part 3, Division 5 of the PAA outlines the core requirements governing their employment, including:

- the employment contract must be in writing, and no longer than 5 years

- the remuneration must be within the Victorian Independent Remuneration Tribunal’s bands, unless advice has been sought

- for eligible executives, a right of return to a non-executive role at the end of their executive employment.

For public entities, the Public Entity Executive Remuneration (PEER) Policy applies. The PEER Policy, which is an order made by the Governor in Council under section 92 of the PAA, requires:

- the classification of executive roles

- executive remuneration to be within the Victorian Independent Remuneration Tribunal’s bands, unless advice is sought

- standard contractual terms, including maximum contract length, termination provisions and restrictions around bonuses.

For public entities which utilise public service employment arrangements, the PEER Policy stipulates these obligations with reference to the VPS framework.

Funding arrangements

What funding sources and financial delegation arrangements are appropriate?

Different funding and financial management arrangements apply to public service bodies and to public entities.

Departments receive an annual budget appropriation allocated by Parliament through the annual Appropriation Act and may collect revenue from the sale of goods and services or from fees and other charges.

Public entities typically have a variety of funding sources. They may receive a direct funding allocation from Parliament or receive funding from a department as a grant from the department’s appropriation from Parliament. rely on a portion of the funding granted to a department. Some public entities also receive funding from the Commonwealth. Public entities may also derive some or all of their income from the sale of goods and services or from fees and other charges.

If the entity collects its own revenue, you should consider whether it can keep all this revenue. An entity should only be able to retain all its revenue where there is a compelling policy justification, as this reduces flexibility in the government’s broader financial management of the State.

In all cases, the relevant minister is responsible for the expenditure of the public entity’s funds.

The funding required by public entities may differ, depending on the functions performed by the entity. In general, if a public entity has the power to employ staff, rather than having staff made available by the portfolio department, it should have financial autonomy from the department (this is not true for AOs, as they are public service bodies, not public entities). In some cases, smaller entities may still have their finance functions as a shared service with their portfolio department, even though they are making autonomous financial decisions. The establishing legislation should make the relevant financial powers available to the entity and specify desired financial delegations.

Financial autonomy will carry a range of financial accountability requirements with it. Specific advice should be sought from the Department of Treasury and Finance.

The Department of Treasury and Finance provides resources to assist public entities to meet their accounting and financial reporting obligations, and support with planning and budgeting processes.

Further information can be found on the financial management of government website.

Updated