- Published by:

- Department of Premier and Cabinet

- Date:

- 12 June 2025

About this guidance

The Victorian public sector performs a wide variety of functions, including:

- delivering services to the community

- providing policy advice

- managing public money

- regulation

- funding and contracting private and non-government organisations for service delivery.

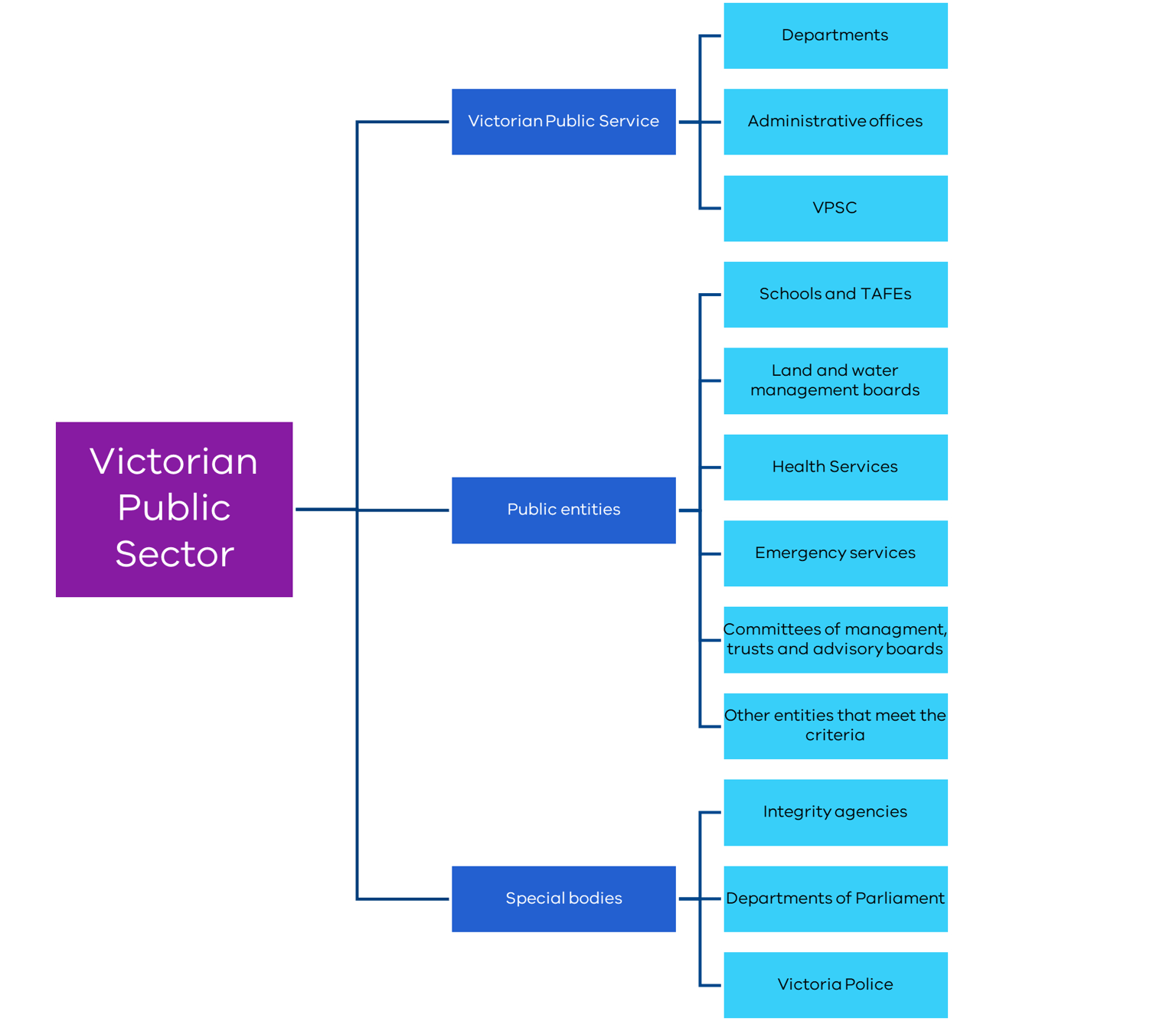

These services are delivered through the public service (departments, administrative offices and the Victorian Public Sector Commission) and through public entities and special bodies operating in the wider public sector.

Adopting suitable legal forms and governance arrangements for the functions and activities being undertaken by public entities is critical for high quality performance.

The ‘legal form’ of a public entity refers to:

- the way it is created — whether this be through a legislative or a non-legislative process – for example:

- a statutory authority which is a public entity that is established by or under Victorian legislation

- a non-statutory body established by a minister or Governor in Council

- a corporation established under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Corporations Act)

- its status as an incorporated or unincorporated body.

Having well considered and fit for purpose forms and arrangements:

- provides a foundation for effective and efficient governance and management

- helps ensure that bodies are accountable, responsible and support public trust in government institutions.

In contrast, bodies with poor alignments between function, form and governance arrangements can:

- impede high performance

- create inefficiencies and costs

- diminish levels of public accountability and transparency.

Who the guidance is for

This guidance is designed to help department policy officers explore possible legal form options when establishing or seeking to change the form of non-departmental entities.

This guide will set out important things to think about when you’re designing a new entity, including:

- legal forms

- mechanisms for establishment

- functional implications

- governance and employment arrangements

- the financial management implications for the entity and the state

- how to establish, manage, review and dissolve public sector bodies.

How to use the guidance

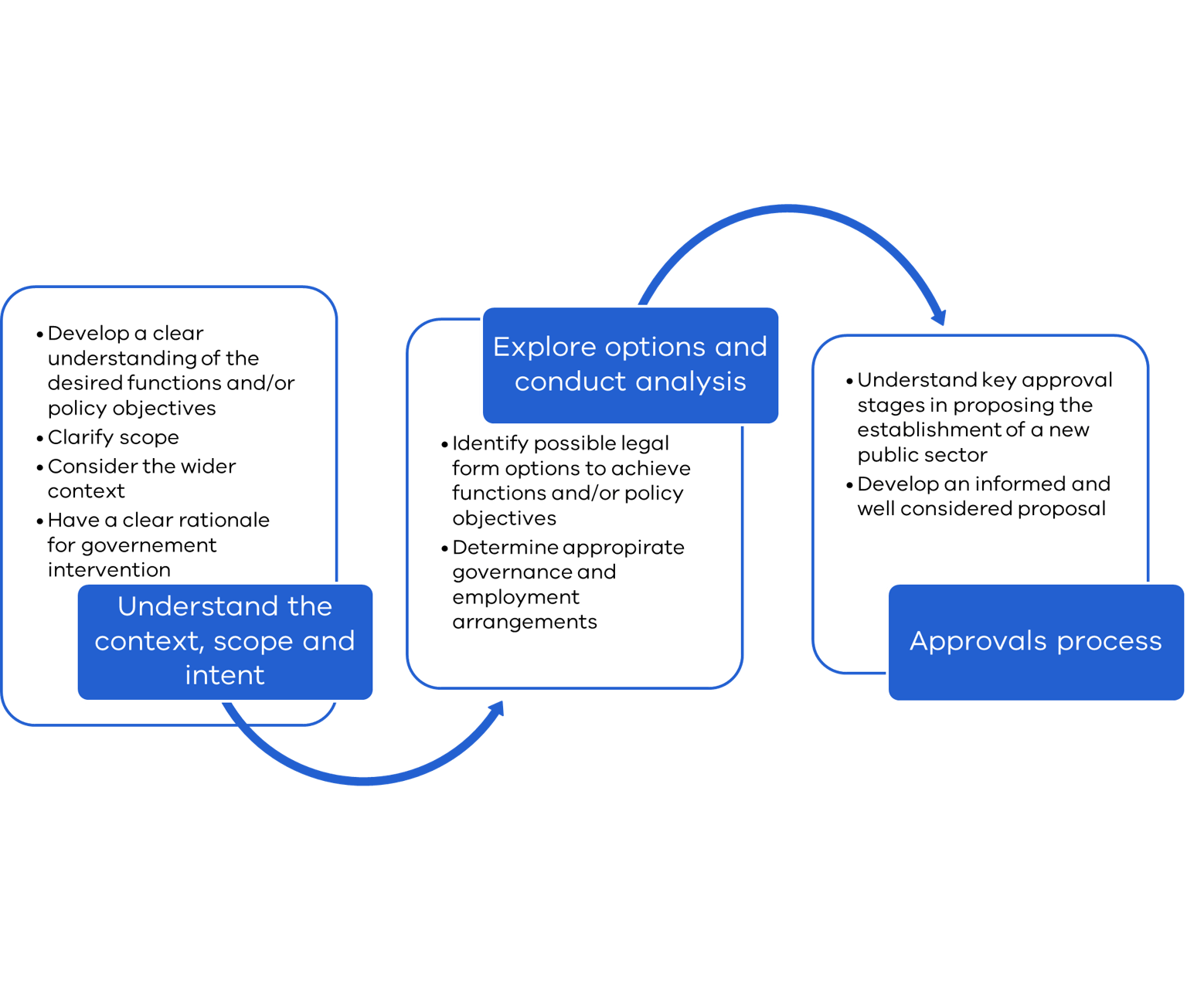

This guidance is organised around three key steps policy officers should follow when designing or reviewing a public sector body.

Key terms

- Administrative office: a public service body established by the Governor in Council under section 11 of the Public Administration Act 2004 (PAA) in relation to a department.

- Non-departmental entity: administrative offices, public entities and special bodies. Does not include departments.

- Public sector body: a public service body, public entity, or special body.

- Public service body: a department, administrative office or the VPSC.

- Public entity: As defined under section 5(1) of the PAA, public entities undertake a public function or are owned by government. A public entity is established by an Act of Parliament, Governor in Council or a minister. In the case of a body corporate, at least one half of the directors are appointed by the Governor in Council or a minister.

- Special body: entities listed as special bodies under section 6 of the PAA, or declared to be special bodies by the Governor in Council.

- Statutory corporation: a body corporate established under legislation or a state body established under the State Owned Enterprises Act 1992.

For more definitions refer to Common terms and acronyms

Deciding to create a new non-departmental entity

Non-departmental entities should only be created when there is a compelling reason to do so. This page outlines factors you should consider before proposing the creation of a new entity, and other options that may be available.

Before you begin

Before you begin to design a new non-departmental entity, you should ensure you understand what the Victorian public sector does and the key features of departments, administrative offices and public entities.

Read more:

This guidance is general in nature. You should ensure that you understand the relevant pieces of legislation that govern the establishment of public sector bodies, starting with the Public Administration Act 2004. As you progress through the process of deciding on the best form for the public sector body there will be other legislation that you should read and understand.

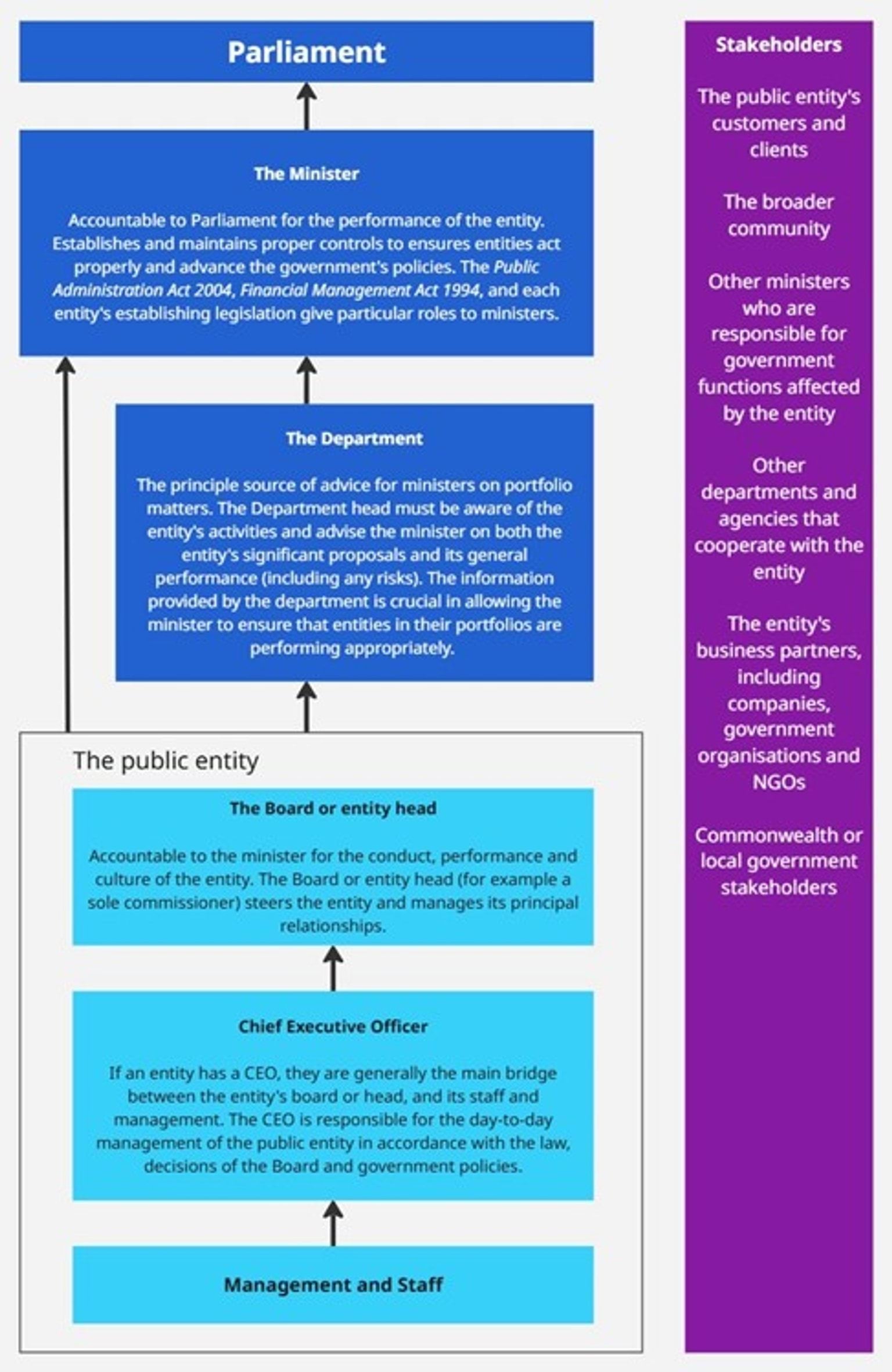

The figure below provides an overview of the Victorian public sector and how it is organised.

Initial considerations

Non-departmental entities exist in a variety of legal and other forms. Before deciding on the right form you should consider:

- why a new entity is needed

- how new entities are created

- how their functions relate to existing entities.

Premier's Circular

The Premier’s Circular No. 2013/2: Creation and Review of Non-Departmental Entities (the Circular) outlines the policy for the creation and review of entities.

The Circular outlines four criteria which much be addressed when proposing the establishment of a new non-departmental entity:

- Is there a role for government?

- What degree of autonomy from departments or ministers is required?

- What is the appropriate form of entity?

- Can the functions be performed by an existing entity?

This guidance provides a framework to explore the criteria. It also sets out a requirement that entities must be reviewed regularly to ensure that they are operating effectively and are still necessary.

The following questions should be worked through to assist in determining whether it is appropriate to create a new non-departmental entity.

The Premier’s Circular also outlines review requirements for entities. This Guidance may assist in evaluating whether the governance structures of the entity have been set up in way that is appropriate for the way the entity is required to operate in practice.

A copy of the Circular is available upon request from the Department of Premier and Cabinet’s (DPC’s) Governance Branch at publicsectorgovernance@dpc.vic.gov.au

Section 8B of the Financial Management Act 1994

While the policy rationale underpinning a proposal to establish or abolish an entity, including stakeholder engagement, are the responsibility of the relevant minister, Section 8B of the Financial Management Act 1994 requires the relevant portfolio department to notify the Department of Treasury and Finance of any proposed establishment or abolition. Section 8B mandates the following requirements:

8B Establishment or abolition of certain entities

- A Minister (other than the Minister administering this section) who intends to establish a body, office or trust body must consult the Minister administering this section before the body, office or trust body is established.

- A Minister (other than the Minister administering this section) who intends to abolish a body, office or trust body must consult the Minister administering this section before the body, office or trust body is abolished.

- Notice of the establishment or abolition of a body, office or trust body by a Minister must be published in the Government Gazette by that Minister

Section 8B requires that a minister who intends to establish a new body, office, or trust body, or abolish an existing one, must consult with the Minister for Finance (who is the minister administering Section 8B) before the entity is established or abolished.

Section 8B also requires notice of the establishment or abolition of an entity to be published in the Victorian Government Gazette.

The term 'body, office or trust body' means a public sector entity that for either operational or reporting purposes, or both, will be separate from any already existing entity.

Detailed guidance on the consultation process can be found in the Department of Treasury and Finance's transitional guidance document; Implementation of the Financial Management Legislation Amendment Act 2025.

A copy of the guidance can be provided upon request by the Department of Treasury and Finance's Frameworks team at financial.frameworks@dtf.vic.gov.au.

What are the functions and policy objectives?

The functions and policy objectives of an entity should inform its legal form.

Most non-departmental entities have more than one function. Often, the primary function of an entity will determine its form. However, all functions should be assessed when determining the appropriate form of the entity, including when merging existing entities. For example, an entity might have a secondary function that involves reporting on a department’s performance, which means that the entity should not be established in a form that is subject to the direction of the Department Head.

Consider the following:

- What are the desired functions and/or policy objectives?

- What is the primary function?

- Are there any functions that could not be fulfilled by a certain type of entity?

- What are the day-to-day activities required to achieve the functions and policy objectives?

Read through the table below which outlines functions of the public sector.

| Function | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Service delivery | Directly undertake delivery of essential public services |

|

| Stewardship | Manage public assets Custodial or stewardship of publicly owned assets |

|

| Integrity | Examine the actions or decisions of public officials with a focus on prevention, scrutiny and detection |

|

| Regulatory | Regulate one or more services or sectors |

|

| Quasi-judicial | Exercise quasi-judicial powers |

|

| Advisory | Provide advice directly to a minister or ongoing research |

|

What is the role for government?

For a new public sector body to be established, there must be a clear reason for the functions to be performed by government.

Assess whether government performing this role maximises net benefits for the community. This can include a mix of policy and governance considerations.

Consider issues such as:

- Is there a legal requirement for the function?

- Has a specific policy decision been taken for government to achieve a policy outcome that requires this function?

- What are the benefits and risks of government performing this role?

- Will government performing this function maximise the net benefits for the community?

- What would be the cost and impact of not delivering this service or function?

- Is there a market failure?

- Does the activity involve providing goods and services in a market?

- Can it be contracted?

- Do alternative non-government providers exist (or could exist)?

While this can be a complex question, consideration of this criterion should, at least, ensure that there is a clear reason to establish a new non-departmental entity.

Can some of all of the proposed functions be performed by an existing entity?

For a new public sector body to be established, consider whether the functions can be delivered by an existing entity. Where a similar or appropriate entity already exists, that entity should perform the additional proposed function to avoid additional cost and complexity.

Consider the following questions:

- Do any existing entities perform similar functions?

- Do any existing entities deal with similar industries, clients or stakeholders?

- Are the powers and governance arrangements of entities performing similar functions appropriate to achieve the proposed function?

- Can the remit of existing entities be expanded to accommodate the proposed functions?

The VPSC maintains a list of current Victorian government employer bodies, which can be searched for employing public sector bodies by industry and sub-sector group. The list can be accessed on the VPSC's list of public sector employers.

In addition, the VPSC maintains the Government Appointments and Public Entities Database (GAPED) which provides information of Victorian State Government boards and committees. It can be filtered by department and portfolio fields to identify any existing non-departmental entities performing similar functions. You can find it online at Public Board Appointments Victoria.

Read more about the Government Appointments and Public Entities Databse Administrative Guideline.

Is a new public sector body required?

In general, the default position is that functions should be performed by a department.

The creation of a new non-departmental entity may be appropriate if:

- No existing public entity or public service body performs similar functions, and the functions of an existing body cannot be expanded to undertake additional functions.

- Effective delivery of the function requires operational autonomy from a department, often including the employment of dedicated staff.

- A more structured, limited or specific level of ministerial oversight and powers are required to deliver the functions (in comparison to a department).

- Independence from the Crown is required, for example when the government may be bound by the decisions of the non-departmental entity or the entity is established to scrutinise the government’s decisions.

- A clearly defined range of specialist functions may improve efficiency and effectiveness, by allowing those governing and managing the entity to focus solely on the defined role.

- The function is discrete and expected to be time limited.

Alternative models

If the above considerations do not apply, there may be alternative models to deliver the proposed function.

Function performed by an existing body

If an existing public entity or public service body performs similar functions and can be expanded to deliver additional functions, it should be delivered by an existing body.

If the existing body is a public entity, you may need to change the functions, governance arrangements, or powers of the body. How this is done depends on the legal form.

Function performed department

Business units or branches can be established within a department with separate ‘brands’ or identities. Examples include Consumer Affairs Victoria, Agriculture Victoria, and the Victorian Schools Building Authority.

Informal groups

Advice can be sought using groups that do not require formal establishment from a wide range of stakeholders across industry and the community, and experts. For example, through roundtables or online consultation.

What type of body should be created?

This page provides guidance on the three main types of non-departmental entities: public entities, special bodies and administrative offices

Differences between non-departmental entity types

There are three broad forms of non-departmental entities that can be established:

- public entity

- special body

- administrative office.

This section will explore the differences between a public entity, special body and an administrative office. You can find more detail about creating public entities and administrative offices below, as almost all non-departmental entities should fall into one of these two categories.

When is establishing a public entity appropriate?

New public entities should only be established where it can be demonstrated that this is the most effective and appropriate means of carrying out the desired function.

This guide refers to public entity functions being performed at ‘arm’s length’ from routine ministerial control. This means that public entities perform their functions with a degree of autonomy from a minister’s decisions. While public service agencies are generally directly accountable to ministers, most public entities are generally accountable to a governing board or independent appointee, who are accountable to the responsible minister.

In general, the creation of a public entity should only be considered if:

- There are strong reasons for a function to be performed at arm’s length from routine ministerial control. For example, if greater independence promotes greater public confidence in decisions made.

- There is no existing public sector body that performs similar functions, and an existing body cannot be expanded to perform the identified function.

- Independence from the Crown is required due to the nature of the functions. For example, if the government may be bound by the public entity’s decisions, or the public entity is established to scrutinise government actions.

- The entity has a clearly defined range of specialist functions which require those governing and managing the entity to focus solely on their defined role.

- In the case of an advisory function, there is a need for ongoing independent, expert advice to ministers or the government on technical or other specialised issues.

Benefits and risks

Creating a public entity provides both benefits and risks to government.

A public entity’s increased autonomy relative to a department and arm’s length from ministerial direction may result in:

- A benefit of improved performance due to greater operational flexibility. This can promote efficient decision making and innovative solutions to problems.

- A risk of fragmentation by exposing the government to wider financial and employment risks. This can happen due to less standardised direction and control mechanisms. For example, it is more difficult to ensure public entities comply with whole of government policies.

When is establishing an administrative office (AO) appropriate?

AOs are used to perform a range of discrete advisory, support, project, service delivery and regulatory functions. In most cases, government functions should be carried out by departments or public entities.

Generally, an AO should not be assigned functions in legislation. AOs are intended to be flexible, as they can be created and abolished by an Order issued by the Governor in Council. Assigning legislative functions to an AO removes this flexibility

Statutory functions can sometimes be delegated to an AO or its Head, rather than to the minister or portfolio department. This is possible if the relevant legislation, other than the Public Administration Act 2004 (PAA), allows such a delegation. In rare circumstances, this may be a useful administrative form for public functions that require close oversight or that cross portfolio boundaries.

In summary, the establishment of a new AO may be appropriate if:

- the function is discrete and the proposed activities can be clearly specified (such as advisory, support, project, service delivery and regulatory functions)

- effective delivery of the function requires operational autonomy from a department, including the employment of dedicated staff, separate internal structures and non-financial processes which allow them to operate with significant managerial flexibility is appropriate

- the function can be performed within the financial processes and oversight of the department such that the Department Head can meet their responsibility for the financial management of the AO

- the function cannot be performed by an existing entity

- close ministerial oversight is expected

Benefits and risks

AOs have multiple and overlapping reporting lines that require careful management. The AO Head is responsible to the relevant Department Head (other than for any legislated functions) and also has the same obligations as a Department Head in relation to the AO. This means that the AO Head is responsible to both the Department Head and minister for the general conduct and the effective, efficient and economical management of the functions and activities of the AO, and must advise them both on any matters related to the AO.

In comparison, departments and public entities generally have clearer lines of accountability.

AOs do not have a separate legal identity from the Crown in right of the State of Victoria. They can be thought of as business units within a department with a defined degree of operational autonomy from the Department Head. This is beneficial if there is a discrete set of functions that need minimal day-to-day control from the department, but do not need to be performed by a legally independent entity.

Another advantage is that AOs can develop and maintain strong branding and a separate identity from their department in pursuing their narrower functions. This is not individually a compelling enough reason to establish an AO—business units in departments can also establish separate branding.

Because AOs have separate internal structures and non-financial processes, including a degree of managerial autonomy, AO Heads have independent employment powers. This means that the employees of an AO are employees of the AO Head.

AOs must be incorporated within the department’s annual financial report under the FMA, so they must operate within the oversight of the department head in relation to all financial matters. If the Department Head is not given clearly oversight over the AO’s financial matters, this compromises the Department Head and department CFO’s ability to sign off on the department’s financial statements for Parliament.

Summary of differences between a public entity and an AO

This table summarises the key differences outlined above between public entities and AOs:

| Characteristics | Public entity | Administrative Office |

|---|---|---|

| Functions and/or policy objectives | A wide range of functions at an arm’s length from ministers, including:

| Provide discrete groups of services and functions with activities can be clearly specified, including:

|

| Governance structure | Typically has a governing board appointed by the minister. The board of a public entity is accountable to a minister or ministers of the government. | The AO Head employs staff and is at least partially responsible to the Department Head. AO head has significant managerial autonomy over non-financial matters. The AO Head is responsible to the portfolio Department Head for the AO’s general conduct and the effective, efficient and economical management of its functions and activities under section 14 of the PAA, including financial management as the Departmental Head retains ultimate responsibility for financial matters. AOs may also have statutory functions that are performed independently of the responsible Department Head. |

| Relationship with the minister | Degree of ministerial control varies across different entities with different functions. Minister’s powers of direction identified in establishing instrument. | Minister may have high level of direction and control through the Department Head. AO Heads have the same responsibilities in relation to an AO as a Department Head has in relation to a Department, meaning that they must advise the minister on matters relating to the AO. |

| Relationship with the Department Head | The Department Head of the relevant department is responsible for advising the minister on matters related to the entity, including about how it is exercising its functions. | An AO Head is responsible to the Department Head for the exercise of the AO’s functions and must advise the department on all matters relating to the AO. This responsibility to the department does not displace the AO Head’s obligations to advise the minister on matters relating to the AO.

|

| Financial arrangements | Various sources of funding, including appropriation administered by the monitoring department, commercial revenue, fees, fines, levies etc. Usually subject to FMA and subordinate instruments (Standing Directions) | Usually funded through relevant department. The AO must be combined into the overall department’s Annual Financial Report, and the Department Head is responsible for ensuring the AO complies with all the financial management obligations that apply to the department. Not separately subject to the FMA and subordinate instruments (Standing Directions), as these are applied through the related Department. |

| Legal form and status | Many possible legal forms Generally, a separate legal status to the Crown. | No separate legal identity. Part of the Crown. |

| Benefits | Potential improved performance due to greater operational flexibility which promotes efficient decision making and innovative solutions to problems. Necessary if independence from departmental or ministerial control is required. | Greater operational freedom from the department, except in relation to financial management. This can be useful when completing a discrete function that does not require day-to-day direction from the department. Can be established quickly compared to a statutory public entity.

|

| Risks | Potential risk of fragmentation by exposing the government to wider financial and employment risks because of less standardised direction and control mechanisms. For example, adherence to whole of government policies more difficult to enforce. | Multiple and overlapping lines of accountability, requiring careful management, particularly to ensure that all key personnel can meet their legal obligations, e.g. the Department Head’s legal responsibility for the financial management of the AO. |

Exploring public entity legal form options

Public entities may be established using several legal forms. This guidance helps you explore the different options available.

In Victoria, public entities may be established using several legal forms.

The ‘legal form’ of a public entity refers to:

- the way it is created — whether this be through a legislative or a non-legislative process:

- a statutory authority established by or under legislation

- a non-statutory advisory body established by a minister or Governor in Council

- a corporation established under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Corporations Act)

- its status as an incorporated or unincorporated body.

There is no simple system for matching functions and legal forms. The variety of legal forms gives rise to a range of legal terms and descriptions, some of which overlap. For example, state owned enterprises (SOEs) are a form of statutory authority.

The focus of this information is on providing guidance on establishing the different forms. The guidance describes a generic version of each legal form but these can be modified and tailored to suit the circumstances of a given public entity (although this does carry some risks—see 'Statutory Authorities' below). This information may also be useful when undertaking a review of an existing public entity.

There is also flexibility to determine the specific governance arrangements that will apply to a particular public entity. See public entity governance arrangements for more detail.

Incorporated or unincorporated

When selecting a legal form, the first step is to select between an incorporated or unincorporated body.

Incorporation provides a separate legal identity for the public entity, which protects the liability of members of the public entity to a greater extent than an unincorporated body. Liability means that you are legally responsible for something. In an unincorporated body members may be liable for the actions of other members. to a greater extent than an incorporated body.

Incorporation is necessary if the public entity is to:

- employ staff

- provide services to non-government parties

- own or lease property or other assets

- receive funding from direct budget allocation and/or other sources

- enter into contracts

- perform functions which expose it to potential legal challenge

- take legal action against others.

Incorporated public entities are used for a wide range of functions and have several legal forms, including:

- statutory authorities

- SOEs

- Corporations Act companies

- incorporated associations

Unincorporated bodies can be used for activities such as mediation, facilitation, and dispute resolution. Unincorporated bodies also are often an appropriate form for non-statutory advisory bodies.

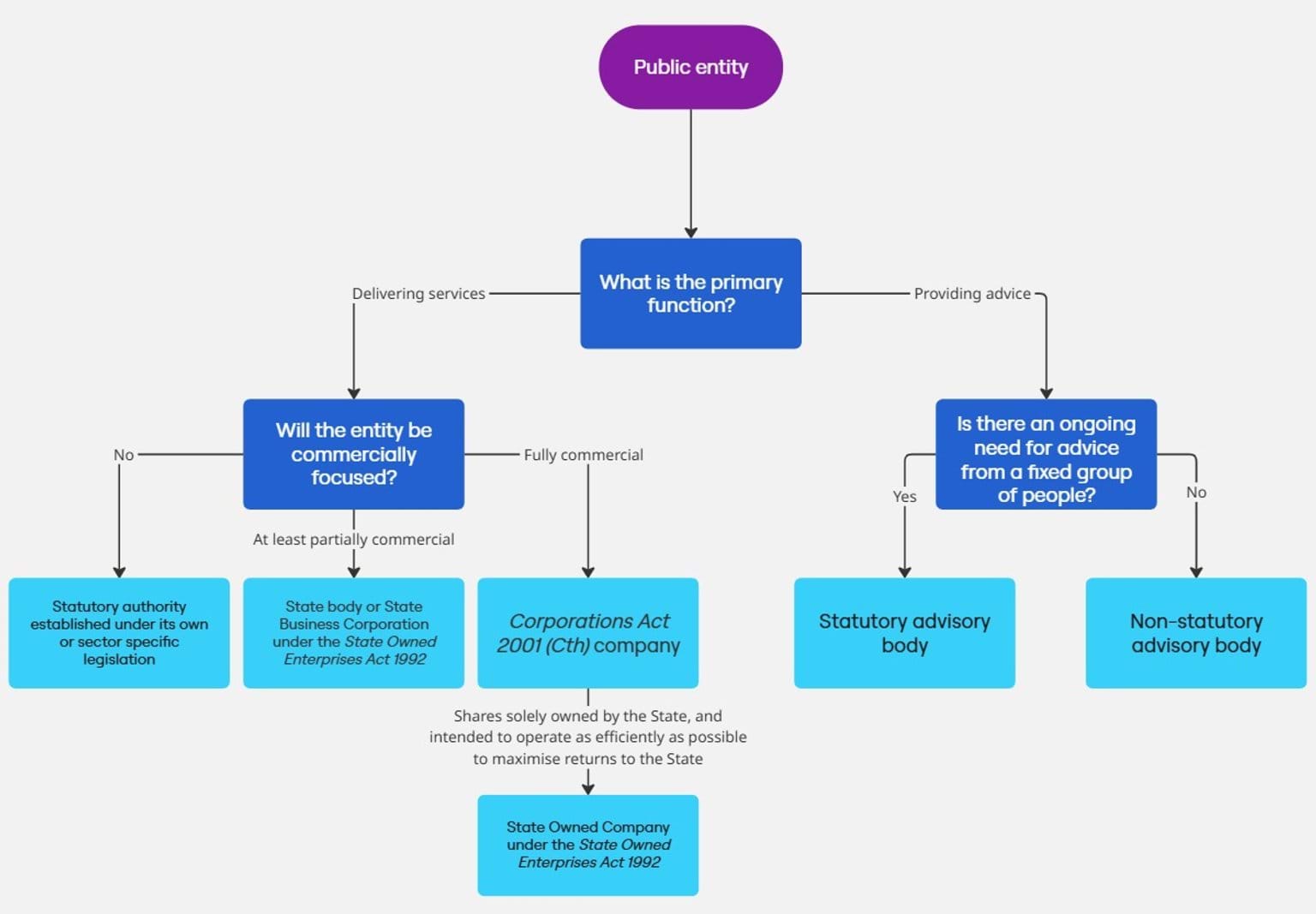

Consider the functions

When exploring the possible suitable legal forms of a public entity, you should consider what functions the entity will undertake. As previously discussed, public entities often perform multiple or hybrid functions.

Use the decision tree below to help find possible legal form matches.

Statutory authority

A statutory authority describes a public entity that is established by Victorian legislation.

A statutory authority may be appropriate when functions require:

- operational independence from ministerial influence,

- legal independence from the Crown.

In general, a statutory authority is the most appropriate legal form for entities that are perform specific functions that cannot be undertaken by a public service body and are broader than the provision of advice. Refer to the Advisory bodies resource <link> for more information for public entities undertaking advisory functions.

There are no predetermined legal rules for the establishment of a statutory authority, giving significant flexibility to tailor the governance arrangements to the specific entity. However, as far as possible, new statutory authorities should attempt to establish governance arrangements that are consistent with other similar entities, as novel governance arrangements can result in non-compliance.

Public entity governance arrangements provides greater detail on:

- appropriate level and forms of ministerial direction and control

- governance structures

- employment arrangements

- the application of whole of Government legislation

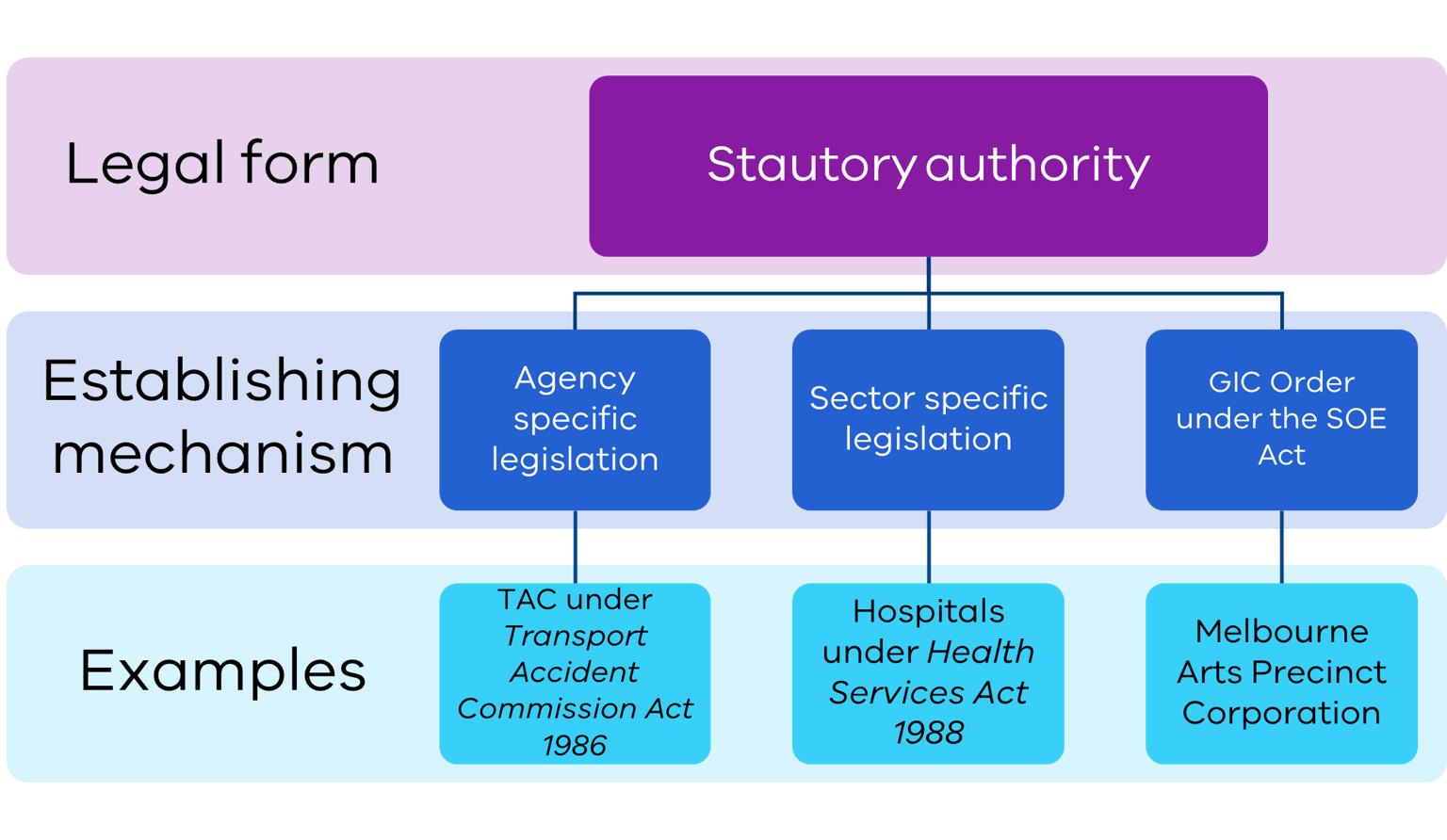

Establishing mechanisms

There are three ways a statutory authority can be established:

- agency establishing legislation (‘own legislation’)

- sector-specific enabling legislation (‘legislative framework’)

- the SOE Act.

The different legislative mechanisms to establish a statutory authority are compared in the table below.

| Agency-specific establishing legislation | Sector-specific enabling legislation | SOE Act | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Considerations | Allows for the provision of clear direction on the objectives, functions, purpose, and operation of the statutory authority, for example through the establishing legislation itself. This also provides a public record of the government’s purpose in establishing the entity. Significant lead times may be required to establish the entity and it can be a lengthy and highly visible process to amend or repeal the legislation. | Provides a legislative framework under which multiple statutory entities with similar functions and activities can be established. The initial development and establishment of legislation can have a long lead time (as is the case for agency-specific establishing legislation). Once legislation is in place, the establishment of new public entities can be achieved relatively quickly. These entities are also easier to abolish. | The SOE Act enables public entities to be established by the Governor in Council, without new legislation being passed by Parliament. |

| When to use | To establish ‘stand-alone’ bodies with unique functions, objectives and powers. | May be more appropriate where there are multiple entities with similar purpose and functions. | May be appropriate for those delivering services in a commercial manner. |

| Examples | Transport Accident Commission established by the Transport Accident Act 1986 The Victorian Managed Insurance Authority established by the Victorian Managed Insurance Authority Act 1996 | Community health centres and hospitals established under the Heath Services Act 1988. | Melbourne Arts Precinct Corporation established by the SOE Act. |

State owned enterprises

SOEs are a kind of statutory authority established under the SOE Act.

SOEs are most appropriate where the primary function of the entity is to deliver services in a commercial manner. Services may include direct services to the public or stewardship, integrity, regulatory or other services for government.

Any financial reporting obligations in the SOE Act do not supersede obligations under the FMA. Financial reporting obligations under both Acts continue to apply.

The SOE Act defines four types of SOEs, each with different objectives and functions. The key features of each type are set out below.

Establishing mechanisms

SOEs are created by an Order of the Governor in Council, following Cabinet approval. This means that SOEs can be established quickly. However, they will not benefit from the Parliamentary scrutiny that is required to establish statutory authorities under unique legislation. Orders establishing SOEs are published in the Victorian Government Gazette.

Comparison of SOEs

The below table summarises the information outlined above about the key differences between the different types of SOEs.

| State body | State Business Corporation | State Owned Company | |

|---|---|---|---|

| How is the entity established? | By Order of the GIC, published in the Government Gazette setting out the entity details listed at s 14(2) of the SOE Act. | By Order of the GIC, published in the Government Gazette, a state body or statutory corporation can be declared an SBC. | By Order of the GIC, published in the Government Gazette, a company may be declared an SOC, if the shares in the company are held only by the State* as set out in s 66(1) of the SOE Act. For the meaning of the “State” please refer to the SOE Act. |

| Rules and procedures for governance | Set out in the GIC Order. May be minimal, for example, a multi-member board is not required. | Set out at Part 3 of the SOE Act. Must have a board of between 4 and 9 directors. May be supplemented by specific legislation for an entity. | Set out in the Corporations Act, and a Memorandum of Association which must at least include the provisions set out at Schedule 1 of the SOE Act. |

| Appointments and duties of directors | GIC Order may include provision for the appointment of directors by the GIC. | An SBC must have between 4 and 9 directors, appointed by the GIC (ss 23, 25) on terms and conditions determined by the minister and Treasurer (s 26). Director’s duties are set out in the SOE Act. The GIC may remove a director (s 30). Minister determines terms and conditions of CEO or deputy CEO on recommendation of the SBC board (s 40). | Directors are subject to a range of legal duties including their professional judgment, conflicts of interest and reporting requirements. The core duties contained in the Corporations Act largely codify the common law on directors’ duties. |

| Public accountability / reporting | None under the SOE Act, but standard accountability and reporting obligations for public entities.

| None under the SOE Act, but standard accountability and reporting obligations for public entities. | The Treasurer must ensure an SOC’s Memorandum of Association, and Corporations Act directors’, auditor’s and financial reporting is tabled before each House of Parliament. |

| Government accountability / reporting | No reporting is required under the SOE Act, though reporting requirements may be drafted in the GIC Order. Additional requirements may be incorporated into the GIC Order. | The board is obliged to notify the minister and Treasurer of “significant affecting events” (s 54). An SBC must provide at least half-yearly reports on its operation to the minister and Treasurer (s 55). The minister can require any information to be provided in the report. The Treasurer may at any time request a report from the board (s 53). | The Treasurer may require an SOC to prepare and deliver financial reports, business plans, annual reports or other information. |

| Government control or direction | After consultation between the Treasurer and the relevant minister, either may, from time to time give directions to the board by written notice (s 16C of the SOE Act). | Limited to input into and influence of an SBC’s mandatory corporate plan and statement of corporate intent (ss 41-43). The minister, with the Treasurer’s approval, may direct the board to perform or cease to perform non-commercial functions (s 45). An SBC action or decision is not legally invalid merely because it does not comply with its corporate plan or the minister’s directions. | The State or Treasurer as shareholder may have the ability to influence the SOC, under the Corporations Act. An SOC is the most independent form of SOE from government. |

| Functions | Functions are drafted in the GIC Order. May be broad or specific, or more or less “commercial”. | Functions may be drafted in the GIC Order, or by legislation. The principal objective of each SBC is to perform its functions for the public benefit by— (a) operating its business or pursuing its undertaking as efficiently as possible consistent with prudent commercial practice; and (b) maximising its contribution to the economy and well being of the State. | Functions may be drafted in a constitution, or by legislation. The principal objective of each SOC is to perform its functions for the public benefit by— (a) operating its business or pursuing its undertaking as efficiently as possible consistent with prudent commercial practice; and (b) maximising its contribution to the economy and well being of the State. |

| Nature and source of powers | Powers must be set out in the GIC Order (s 14(2)(b)). May have such powers under the Borrowing and Investment Powers Act 1987 (Vic) as are conferred on it by GIC Order (s 14A). This also requires an update to the BIP Act’s regulations.

| Under the SOE Act, an SBC can do all things necessary or convenient to be done for, or in connection with, or incidental to, the performance of its functions (s 20). Powers and functions apply within and outside Victoria and Australia (s 21). | Powers established by virtue of the SOCs incorporation and legal status (under statute and at common law). No power to bind State or render State liable for any debts, liabilities or obligations of the SOC (s 70). |

| How is the entity dissolved? | By GIC Order on the recommendation of the Treasurer and relevant minister. | By GIC Order on the recommendation of the Treasurer and relevant minister. The underlying entity would need to be separately abolished once it ceases to be an SBC. | By GIC Order on the recommendation of the Treasurer and relevant minister, and the process outlined in Part 5.5. of the Corporations Act |

Advisory bodies

Departments generally are responsible for providing policy advice. However, in some cases, ministers may choose to establish external advisory bodies to provide specialised advice that cannot be provided by the department.

An advisory body should only be formally established as a non-departmental entity if it is intended to provide advice to a minister, and there is a clear ongoing need for independent advice from a fixed group of members.

A minister can also consult with stakeholders without establishing an advisory body. These less formal options like roundtables should always be considered before deciding to establish a new entity.

If an advisory body is established as a non-departmental entity to provide advice to a minister, there are two legal forms which may be suitable. This section will outline the key differences and considerations between statutory and non-statutory advisory bodies.

Other options where a department or public entity wishes to receive advice

Non-departmental entities are generally established to provide advice to ministers, not departments or other non-departmental entities.

In some cases, departments may wish to receive expert external advice. This advice does not need to be delivered through an entity that is formally established by an instrument and, in practice, can be achieved by engaging relevant experts as contractors. You should refer to the Administrative Guidelines on Engaging Labour Hire in the Victorian Public Service before engaging any contractors.

If the governing body of a public entity requires advice, they also likely do not need to establish a new entity. Many public entities are given the power to engage contractors under legislation, which may be appropriate. Alternatively, public entities can establish sub-committees under section 83 of the Public Administration Act 2004 (PAA). The membership of these sub-committees is not limited to the members of the entity’s governing body, so this can be a way to form advisory committees. These sub-committees do not count as separate non-departmental entities, and they can be created and abolished at the board’s will.

Other legal forms

In addition to statutory authorities and non-statutory advisory bodies, there are other possible legal forms for public entities. These are only appropriate in limited circumstances. and include companies established under the Corporations Act and incorporated associations.

Corporations Act companies

A Corporations Act company should only be used where an entity is to perform functions with a highly commercial focus. This is uncommon in the public sector.

If you are considering establishing a Corporations Act company, you should seek advice from:

- the Department of Treasury and Finance

- the Department of Premier and Cabinet’s Governance Branch.

Companies can be established and incorporated under the Corporations Act. Corporations Act companies in the public sector can be set up as companies limited by shares or companies limited by guarantee. These have different approaches to ownership and liability:

Unlike a State Owned Company, Corporations Act companies are not required to operate as efficiently as possible to maximise their contribution to the economy.

As with SOEs, the reporting obligations under the Corporations Act do not displace requirements under the FMA. Corporations Act companies must comply with both sets of obligations.

Considerations for Corporations Act companies

There are limitations on how much the government can direct and control a Corporations Act company. This is because directors are required to act in the best interests of the company itself, which may not always be consistent with government policy directions.

Following a decision to establish a Corporations Act company, the government’s control over these entities is generally limited to decisions about the composition of the board. Employees and board members remain bound by the public sector provisions of the PAA (e.g., values, code of conduct).

Reporting and other obligations for Corporations Act companies can be substantial and potentially onerous. Given the complications associated with the use of the Corporations Act as a legal form, there are relatively few examples in the public sector.

Incorporated associations

Incorporated associations are entities incorporated under the Associations Incorporation Reform Act 2012, Incorporated associations are non-profit organisations, meaning that they can trade but profits can’t be distributed to members.

This legal form is designed to support small scale community/not-for-profit organisations with little or no capital base, such as a sporting club, or a recreational or special interest group. It offers an alternative to the company form in terms of granting the benefits of incorporation, including:

- being able to enter into contacts

- the entity legally continuing regardless of changes to membership

- protecting individual members of the association against personal liability.

The Associations Act applies differential financial reporting and auditing requirements to incorporated associations depending primarily on their annual revenue, with requirements for review and auditing of financial records escalating as annual revenue increases.

However, governance and accountability standards for the boards and directors of these entities are generally less rigorous than most other public entity forms. Therefore, establishing an incorporated association is generally not appropriate for a new public entity, where performing a public function and exercising public authority require high standards of governance and accountability.

Public entity governance arrangements

Selecting the right governance arrangements for your public entity is critical to ensuring it functions effectively

The previous section of the guidance outlined a framework for matching public entity functions and legal forms. The next stage in designing a public entity involves specifying the governance arrangements to suit the entity’s needs.

The legal framework establishing an entity (such as the establishing legislation, Order-in-Council instrument, or constituting terms of reference) should set out key governance arrangements.

You should think about the advantages and disadvantages of the different governance options.

Guiding questions

- What level of interaction between the entity, the relevant minister and the department (as adviser to the minister) is desirable?

- What specific powers does the minister require?

- How will the board be appointed and what skills are required on the board?

- What are the processes, and under what circumstances could a board member be removed?

- What management structure suits the public entity’s functions?

- How will staff be employed?

- What funding sources and financial delegation arrangements are appropriate?

- What whole of government legislation will apply and how will this be achieved?

- Which government policies will apply to the entity?

- Which code of conduct will apply to the employees and officers (including board members) of the entity being established?

It may help you to review the governance arrangements of existing public entities to understand how the various options work.

In limited circumstances, a public entity may be headed by an individual rather than a board.

Relationship between the entity, minister and department

What level of interaction between the entity, the relevant minister and the department (as adviser to the minister) is desirable?

Public entities have a high degree of autonomy in their operations. However, they are subject to varying levels of ministerial direction regarding compliance with government policies and strategies. On a day-to-day basis, there is a separation between the public entity and ministerial direction.

Under Victoria’s Westminster system of government, ministers are accountable to Parliament and the Victorian community for the performance of their portfolio public entities, consistent with the principle of responsible government.

The nature of the interaction between the entity and the minister is set out in the legislation or other instrument that establishes the entity (such as a Governor in Council establishing order). The powers of the minister to direct the entity should be clearly defined by these instruments.

Determining specific ministerial powers, the degree of independence of the entity and its relationship with the portfolio department is undertaken on a case-by-case basis and depends on the functions and objectives of the entity.

General guidance on the roles and responsibilities of each stakeholder is provided in the following sections.

Memorandum of Understanding

A memorandum of understanding (MOU) should be formed between a public entity and portfolio department to formalise governance arrangements and clarify expectations. MOUs are voluntary statements of intent that set out the commitments of each party. Factors commonly covered by MOUs include establishing communication and briefing processes and agreeing on the corporate costs that will be charged to the public entity.

Sometimes an MOU can also be formed between two or more public entities, particularly where functions may overlap or there is a need for information to be shared between entities.

Ministerial powers

What specific powers does the minister require?

The degree of influence a minister has over any particular entity, and its degree of independence should be informed by the desired functions and/or policy objectives of the proposed entity.

The below section discusses common functions in the Victorian public sector and possible levels of ministerial control to support the body to achieve its functions.

The table below summarises the information provided above about governance arrangements for public entities performing different functions and the impact of the level of control and direction provided by the minister.

| Public entity function | Functional implications | Legal form options | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

Service delivery Directly undertake | High degree of ministerial control over strategic directions and policy. Limited ministerial control over operations due to specialist/technical nature. | Statutory authority, governed by a board or individual appointment. | Melbourne Health (Royal Melbourne Hospital) Roads Corporation |

Stewardship Manage public assets | High degree of ministerial control over strategic directions and policy. Limited ministerial control over operations due to low risk nature. | Statutory authority governed by a board. | Shrine of Remembrance Trust Crown land committees of management. |

Integrity Scrutinise the actions and decisions of public officials | Little or no ministerial control over operational decision making, strategy and direction due to requirement for impartiality. | Statutory authority, generally governed by an individual appointment. | Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission. |

Regulatory Administer regulation | In some cases there can be some degree of ministerial control over strategic directions and policy. Little or no ministerial control over day to day and operational decision making. | Statutory authority, governed by a board or individual appointment. | Essential Services Commission. |

Quasi-Judicial Exercise quasi-judicial powers. | No ministerial control over strategy, operations, or decision making due to requirement for impartiality. | Statutory authority, governed by a board or individual appointment. | Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (VCAT). |

| Advisory Provide advice directly to a Minister or ongoing research | Ministers determine scope of activities but has no control over advice provided | Statutory authority, governed by a board or individual appointment.

Non statutory advisory body | Infrastructure Victoria |

Ministerial Statement of Expectations

A Ministerial Statement of Expectations is a formal and public statement that establishes the expectations the responsible minister has for the public entity. You should consider whether the responsible minister should issue a public entity with a Statement of Expectations. These statements should be mindful of the appropriate relationship between the responsible minister and the entity, ensuring that they do not compromise the independence of entities established at an arms-length from government.

The minister’s Statement of Expectations may outline expectations for a public entity with consideration to:

- a government policy or policies

- the performance, behaviour or conduct of the entity.

Entities that perform regulatory functions may be subject to DTF’s Statement of Expectations Framework for Regulators. More information can be found by accessing Statement of Expectations for Regulators.

Board structure

Is a governing board the best option or should the entity be headed by a single person?

Governance of public entities can be configured as multi member or single member arrangements

A multi-member board of governance is generally the default position when establishing a new public entity and most Victorian public entities operate this way. The Board is charged with making decisions about the direction and operations of the entity and reports to the relevant minister. Board chairs sometimes will have additional powers or responsibilities.

In some cases, individual appointments, such as commissioners, can form a corporation sole, which is where a single person is a legal entity with the status of a corporation or office. This form is more appropriate when the appointee will need to be actively involved in exercising the entity’s functions, while boards are more suited to governance and strategy. If you are considering this option, you should discuss this with Governance Branch, DPC early in the policy process.

If the entity is being established under existing enabling legislation, it may mandate certain decision-making structures. For example, the State Owned Enterprises Act 1992 (SOE Act) requires that state business corporations operate with a board of between four and nine directors.

A multi-member board is should always be the preferred design where:

- the public entity’s functions are sufficiently complex to require a diversity of skills and experience that may not be available if a single commissioner were appointed

- there is a range of functions for the multiple board members to oversee.

A board should include members with a range of different skills, including sufficient finance skills to acquit the board’s responsibilities for the entity’s financial management. A single appointment would need to source any additional skills required from employees (who don’t participate in decision making) or from external sources.

If a board structure is selected, you should consider the number and nature of appointments to the board. To serve their purpose and be effective, boards need to be established appropriately and granted sufficient and clear powers to act as a board. As boards are governing bodies, they should have a skill set that reflects the need for governance expertise across a range of areas. They should not be representative bodies (i.e. composed of representatives from relevant industries).

The number of board members should be related to the anticipated size of the governance task involved. Larger and more complex public entities may require larger boards, while smaller public entities with limited functions and budgets may not require as many board members if the mix of necessary skills can be covered, including sufficient members to form an Audit and Risk Committee. In general, there is a trend towards smaller boards. Even in the case of more complex public entities, you should consider carefully whether more than eight members are genuinely required, noting that large boards can be difficult to manage.

How will the board of individual appointee be appointed?

You will also need to consider how board members or the individual appointee will be appointed.

Appointments may be made by the relevant minister or by the Governor in Council on the recommendation of the minister.

In some circumstances, existing general legislation mandates certain appointment processes.

Guidelines

The Appointment and Remuneration Guidelines outline Victoria’s standard processes for appointing people to government boards and offices. The Appointment and Remuneration Guidelines also provide for the classification of non-departmental entities to inform the remuneration of board members.

Board appointment, remuneration and diversity guidance ensure that appointments to Victorian government entities reflect the diversity of the Victorian community. The Diversity on Victorian Board Guidelines provide advice to support diversity on boards.

Which code of conduct should apply to the board members/ individual appointee?

The Victorian Public Sector Commission issues binding codes of conduct.

Directors of Victorian public entities and statutory office holders are bound by the Code of conduct for directors of Victorian public entities.

Resources to support Victorian public sector board directors and chairs are available on the Boards Victoria website.

Employment arrangements

Key principles

The following key principles should guide consideration of the employment arrangements for a public entity.

Does the entity require staff?

Advisory bodies and small entities usually do not require dedicated staff and can receive relevant secretariat support from the department.

Most other public entities will require staff. Allowing entities to directly employ their own staff is the most common arrangement, although in some cases legislation will specify that the department must make staff available to support an entity instead.

Even where staff are employed directly by the entity, it is worth considering whether some things can be shared with the department of other entities to create efficiencies and reduce organisational costs, such as:

- Office accommodation

- administrative systems such as:

- IT systems

- finance and accounting

- legal services

- payroll and human resources functions.

You should consider these options as part of the entity design process to reduce future costs associated with migrating functions after the public entity is established.

How will staff be employed

For public entities to directly employ their own staff, the public entity needs to be provided with employment powers.

The available options depend on the legal form of the entity:

- Statutory authority – power is generally specified in the entity’s establishing mechanism, such as the establishing legislation or establishing Order in Council).

- State owned enterprises excluding State Owned Companies – power must be given in the establishing Order, or through a declaration as a ‘declared authority’ under section 104 of the Public Administration Act 2004 (PAA).

- Corporations Act company (including State Owned Companies) – employment powers are inherently granted through registration with ASIC.

Generally, you should include the employment power in the establishing mechanism so that it is clear how the public entity is able to employ staff.

In exceptional circumstances, public entities may be supported by public service staff employed through a delegated power of employment from the portfolio Department Head. Under this model, the Department Head must sign an instrument delegating their employment powers under Part 3 of the PAA to the Head of the relevant entity for the purposes of employing staff required to execute the entity’s functions. This may be appropriate for very small entities, or as a transitional provision for entities that need to be established urgently. It is a common arrangement for inquiries such as Royal Commissions or Boards of Inquiry. However, this approach creates additional administrative burdens and risks, including potential confusion about reporting lines. Therefore, it is usually not recommended, particularly on a medium or long-term basis.

Who will have the power to employ?

You need to consider who holds the employment power in a public entity.

Options include:

- the board as a collective

- the chair of the board

- the CEO.

Employment powers place significant responsibilities on the person/s who hold the power. This includes obligations to ensure compliance with the relevant:

- Commonwealth and Victorian employment legislation (e.g. legislation covering employment conditions)

- industrial agreements

- organisational policies

- government policies.

In some cases, employers can be personally held liable for outcomes, such as obligations for occupational health and safety.

Case study – industrial manslaughter

In 2024, LH Holding Management Pty Ltd became the first company to be convicted under Victoria’s industrial manslaughter laws. A worker was crushed by an overloaded forklift. The company plead guilty to the charges that it had failed to take reasonably practicable steps to ensure that the forklift was operated safely.

The company was issued a $1.3 million fine. Its sole director was also found to be personally liable due to his failure to discharge his duties to ensure a safe workplace. He was sentenced to community corrections order for two years. Both the director and the company were ordered to jointly pay $120,000 in restitution to the family of the deceased worker.

In addition to these responsibilities, public sector employers are likely to be held accountable for the actions of their employees by integrity bodies such as the Victorian Ombudsman, the Auditor-General and the Independent Broad-based Anti-Corruption Commission.

Preferred employment model

For entities governed by a board, the preferred model is that the board (as a collective) holds the power to employ the CEO and all other staff. In some instances (for example, when a public service body head needs to be declared), the employment power is held by the board chairperson instead of the board as a collective. The board chairperson should then formally delegate the power to employ all other staff to the CEO.

The power to delegate employment powers should be included in the legislation. The CEO should consider whether to delegate these powers to others, such as executive officers and others below CEO level. This will generally require board approval. These powers generally need to delegated by instrument. You should consult with your legal area about what these instruments need to involve.

Providing employment powers directly to the CEO is generally not recommended. This may dilute or confuse accountability of the CEO to the board for employment decisions.

When a board delegates employment powers to the CEO it ensures that the board has oversight of this key area of the entity’s operations and the CEO. This is appropriate as the board is responsible for governance and the CEO is responsible for day-to-day operational and management decisions. This model is also used in the private sector.

Boards should be clear that when they delegate employment powers they remain accountable for employment matters. The CEO is responsible for controlling employment decisions only. The board remains accountable for the actions of the delegate and needs to take appropriate steps to ensure that the delegate acts appropriately.

Appointment of the public sector body Head

In general, the CEO is appointed by the board, in consultation with the relevant minister. For a statutory authority, the terms of appointment are prescribed in the body’s establishing legislation.

For a state business corporation, section 40 of the SOE Act prescribes that the CEO and/or deputy CEO are appointed by the minister on the recommendation of the board. However, for other state owned enterprises there is no specified approval process to appoint CEOs outlined in the Act.

In some cases, CEOs (or other second level positions) are appointed by ministers or the Governor in Council, rather than the board. Generally, this model should not be used as it carries particular risks. The risks are demonstrated in the case study below.

Case study – Governor in Council

The board of a public entity has the power to employ staff. The CEO of the entity is appointed by Governor in Council. Recently, a new CEO was appointed by Governor in Council. Initially, the new CEO and the board developed a positive working relationship. However, in recent months, the relationship has deteriorated and the board is concerned that the CEO is not implementing its vision for the entity. In discussions between the chair of the board and the CEO, it is clear that the CEO does not see themself as accountable to the board. The CEO thinks they are accountable directly to government because they were appointed by government. The board is accountable for the actions of the CEO but the CEO is not following its directions.

How to classify Head position

To classify a public entity Head use the Public entity executive classification framework.

The VPSC maintains a handbook on public entity executive employment.

Questions about executive employment policy, should be sent to publicsectorworkforce@dpc.vic.gov.au.

Questions about seeking the Tribunal’s advice on proposals to pay above the remuneration band should be sent to enquiries@remunerationtribunal.vic.gov.au.

What type of staff will be employed?

Public entities can either be given powers to employ their own public service staff under Part 3 of the PAA or employ their own staff under separate enterprise agreements (which in this section will be referred to as ‘public sector staff’).

All public service and sector staff are bound by the majority of the PAA (Part 3 only applies to public service staff). This means that similar rights and obligations are conferred on all staff.

Most public entities employ public sector staff. This allows them to maintain a degree of independence from the government, and to tailor employment conditions to their operational needs, through the use of entity or sector-specific industrial agreements.

The proposed functions of the public entity will also determine what type of staff will be most often appropriate. The table below provides a summary of these most common arrangements. More detail about what these different arrangements involve is provided below.

| Function | Employment powers | Staff |

|---|---|---|

| Service delivery | Powers to be specified in establishing legislation. | Own staff, generally not public servants. |

| Stewardship | Powers to be specified in establishing legislation. | May require staff (depending on functions), generally not public servants. May be volunteers. |

| Regulatory | Powers to be specified in establishing legislation. | Department’s or own staff, who may be public servants employed directly by the public entity Head |

| Quasi judicial | Not usually required. | Departmental staff who are public servants. |

| Integrity | Powers to be specified in establishing legislation. | Department’s or own staff, who may be public servants employed directly by the public entity Head |

| Advisory | Not usually required. | Do not usually require staff. Staff provided by relevant departments. |

Employing public sector staff

Industrial Relations Victoria provides guidance for the public sector on industrial relations matters.

Further information is available on the Industrial Relations Victoria website.

Employing public servants

Public entities can employ staff as public servants. This arrangement is common when government needs to transfer existing public servants to the entity and wants to preserve their existing employment entitlements and conditions. Some agencies also choose this arrangement as their staff are clearly fulfilling functions that are similar to those of a public servant (for example integrity agencies). Some of these agencies are also declared to be special bodies to reinforce that their staff are not subject to ministerial direction.

However, there are some complexities to this arrangement, and the decision should be carefully considered in light of legal and industrial relations advice. You should also consult with DTF about any implications this decision will have under the Financial Management Act 1994 (FMA).

If required, there are several options for a public entity to employ public servants. These options are detailed in the below table.

Employment of public servants should generally be achieved through section 16(1) of the PAA, to ensure that all elements of the Act relevant to the employment of public servants, and any future amendments, are applied. Note that using this option means that the entity is automatically treated as a department under the FMA and therefore it is required to comply with the same standards of financial management as major departments. Using this option also ensures clarity about the status of the entity as part of the public service. DPC’s Governance Branch can be contacted if you wish to discuss this further.

Some public entities have employed a mix of public sector, public service and (in a small number of cases) non-government staff. This option is not recommended on a medium or long-term basis as it creates challenges for entities in ensuring consistent employment conditions and career opportunities for staff and creating a unified culture. It is only potentially appropriate where employers have two clearly distinct cohorts of staff (for example, if an entity employs a large policy team, but also needs clinical staff).

The below table outlines the options to employ public servants in public entities

| Options | Implications | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Preferred options | ||

Amend s. 16 of PAA Amend s. 16(1) of the PAA to declare a particular officeholder a ‘person with the functions of a public service body Head’ for the purposes of the PAA |

|

Refer to s. 16 of the PAA |

Order in Council declaration Obtain Order in Council under s. 16(3) of the PAA to declare a particular office holder a ‘person with the functions of a public service body Head’ for the purposes of the PAA |

|

Refer to Orders made under s. 16 of the PAA |

| Other available options | ||

Establishing Act Include provisions within the entity’s establishing act to provide a particular office holder with the powers to employ public service staff |

|

|

Declared authority Obtain an Order in Council to declare an entity to be a ‘declared authority’ for the purposes of the PAA Further information: Declared authorities <link> |

|

|

Secretary delegation Secretary of portfolio department provides public service staff by delegation NB: This option is not recommended and should only be used in exceptional circumstances, or for a limited time |

|

|

Employing executives

As with non-executive staff, public sector bodies may employ their executive officers with reference to public service or public sector / entity arrangements. Different employment and remuneration frameworks apply for these two cohorts.

In relation to public service executives, Part 3, Division 5 of the PAA outlines the core requirements governing their employment, including:

- the employment contract must be in writing, and no longer than 5 years

- the remuneration must be within the Victorian Independent Remuneration Tribunal’s bands, unless advice has been sought

- for eligible executives, a right of return to a non-executive role at the end of their executive employment.

For public entities, the Public Entity Executive Remuneration (PEER) Policy applies. The PEER Policy, which is an order made by the Governor in Council under section 92 of the PAA, requires:

- the classification of executive roles

- executive remuneration to be within the Victorian Independent Remuneration Tribunal’s bands, unless advice is sought

- standard contractual terms, including maximum contract length, termination provisions and restrictions around bonuses.

For public entities which utilise public service employment arrangements, the PEER Policy stipulates these obligations with reference to the VPS framework.

Funding arrangements

What funding sources and financial delegation arrangements are appropriate?

Different funding and financial management arrangements apply to public service bodies and to public entities.

Departments receive an annual budget appropriation allocated by Parliament through the annual Appropriation Act and may collect revenue from the sale of goods and services or from fees and other charges.

Public entities typically have a variety of funding sources. They may receive a direct funding allocation from Parliament or receive funding from a department as a grant from the department’s appropriation from Parliament. rely on a portion of the funding granted to a department. Some public entities also receive funding from the Commonwealth. Public entities may also derive some or all of their income from the sale of goods and services or from fees and other charges.

If the entity collects its own revenue, you should consider whether it can keep all this revenue. An entity should only be able to retain all its revenue where there is a compelling policy justification, as this reduces flexibility in the government’s broader financial management of the State.

In all cases, the relevant minister is responsible for the expenditure of the public entity’s funds.

The funding required by public entities may differ, depending on the functions performed by the entity. In general, if a public entity has the power to employ staff, rather than having staff made available by the portfolio department, it should have financial autonomy from the department (this is not true for AOs, as they are public service bodies, not public entities). In some cases, smaller entities may still have their finance functions as a shared service with their portfolio department, even though they are making autonomous financial decisions. The establishing legislation should make the relevant financial powers available to the entity and specify desired financial delegations.

Financial autonomy will carry a range of financial accountability requirements with it. Specific advice should be sought from the Department of Treasury and Finance.

The Department of Treasury and Finance provides resources to assist public entities to meet their accounting and financial reporting obligations, and support with planning and budgeting processes.

Further information can be found on the financial management of government website.

Administrative Office (AO) governance arrangements

Unlike public entities, AOs have relatively fixed governance arrangements. These arrangements are outlined below.

Relationship between the minister, Department Head and AO Head

AO Heads are responsible to both the minister and Department Head. The section below outlines their different roles.

Memorandum of Understanding

The portfolio department and the AO should enter into a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) that sets out how they will work together, what assistance and resources the department will provide and how the AO will report to the department.

A template MOU is available from Governance Branch, DPC.

An MOU provides a formal documented agreement between two parties. It sets out a common understanding between the parties as a voluntary statement of intent and contains the serious commitment of both parties.

In general, the purpose of an MOU is to:

- clarify the nature of the relationship between the parties

- seek to foster a productive working relationship between the parties

- clarify the accountability, functions and responsibilities of each party.

MOU between AO and department

An MOU between the AO and portfolio department formalises governance arrangements. This will clarify expectations for the AO and department. In addition to the purpose set out above, a MOU may:

- establish communication processes, or briefing protocols

- agree to the corporate costs charged to the public entity.

It should be:

- circulated to relevant department and AO employees

- regularly reviewed to ensure it meets both parties’ needs.

Ministerial Statement of Expectations

It is recommended that an AO’s portfolio Minister also writes to the AO Head to issue them with a Statement of Expectations within three months of establishment, and then periodically updates the Statement of Expectations at least once every three years.

At a minimum, an Statement of Expectations should cover the:

- purpose and objectives of the AO

- strategic priorities of the AO

- performance targets and government priorities the AO is expected to work towards

- reporting, resourcing, use of departmental corporate services and any other relevant matters

- roles and responsibilities of the secretary and the AO Head, based on relevant legislation.

Considering that AOs inherently have overlapping reporting lines with the minister and department, the Statement of Expectations and the MOU between the department and AO should be consistent about what level of direct engagement the AO Head will have with the minister, and what should be filtered through the department.

Employment arrangements

All AO Heads are employed by the Premier under section 12(2) of the Public Administration Act 2004. An AO Head falls within the definition of a public service body Head, meaning the Head has powers to employ their own staff on behalf of the Crown.

How to classify the AO Head

To classify an AO Head, use the Victorian Public Service Executive Classification Framework. As the employer of the AO Head, the Premier will make the final determination of the classification of the position.

The Victorian Independent Remuneration Tribunal (VIRT):

- determines the remuneration bands for executives employed in public service bodies <link>

- issues guidelines on the placement of executives within remuneration bands.

If it proposed to pay the AO Head above the maximum of the relevant remuneration band, advice must be sought from VIRT.

Application of whole of Victorian government legislation and policies

It is important for non-departmental entities to understand their obligations under a range of whole of Victorian government legislation and policies.

Application of the Public Administration Act 2004 (PAA)

Regardless of whether an entity employs staff as public sector or public service employees, the PAA confers a range of obligations and rights on both employees and employers.

Employees

All public sector employees are expected to abide by the public sector values outlined in section 7 of the PAA.

In addition, employees are expected to abide by the Code of Conduct for Public Sector Employees which sets the standards of behaviour for public sector employees. The Code of Conduct reinforces the public sector values.