- Published by:

- Family Safety Victoria

- Date:

- 21 Mar 2021

Executive summary

Family violence is an endemic issue, which can have terrible consequences for individuals, families and communities.

Family violence is an endemic issue, which can have terrible consequences for individuals, families and communities. The Victorian Government launched Australia’s first Royal Commission into Family Violence in February 2015 to address the scale and impact of this crime in Victoria.

The Royal Commission into Family Violence (the Commission) held 25 days of public hearings; it commissioned research and held community conversations with more than 800 Victorians. It also received almost 1000 written submissions. The Commission provided a once-in-a-generation opportunity to examine our system from the ground up and put victim survivors at the centre of family violence reform.

The Commission delivered its report in March 2016, with 227 recommendations. The Commission outlined a vision for a Victoria that is free from family violence, where adults, young people and children are safe and where their wellbeing and needs are responded to, and where perpetrators are held to account for their actions and behaviours. Where family violence does occur, the Commission outlined how reform of the service system could provide consistent, collaborative approaches to risk identification, assessment and management.

The Commission noted the strong foundations of the service system and practice environment that had been built by the Family Violence Risk Assessment and Risk Management Framework, also known as the Common Risk Assessment Framework or CRAF. To address key gaps and issues, it recommended a review and redevelopment of the CRAF, and to embed it into the Family Violence Protection Act 2008 (Vic) (the FVPA).

The Victorian Family Violence Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management Framework (MARAM Framework) updates and replaces the CRAF and is informed by consultations with more than 1650 practitioners and subject matter experts, and evidence-base reviews. In addition to the Commission’s findings and recommendations, the redevelopment was also informed by the Coronial Inquest into the death of Luke Geoffrey Batty and the 2016 Review of the CRAF.

More than 855 organisations and 37,500 professionals are currently prescribed to align their policies, procedures, practice guidance and tools to the MARAM Framework.1 Further organisations will be prescribed from 2020.

Fundamental changes identified by the Commission are reflected in the aims for the MARAM Framework. These include:

- Increase the safety of people experiencing family violence

- Ensure the broad range of experiences and spectrum of risk are represented, including for Aboriginal and diverse communities, children, young people and older people, across identities, and family and relationship types

- Keep perpetrators in view and hold them accountable for their actions and behaviours

- Alignment of practice across a broad range of organisations who have responsibilities to identify, assess and manage family violence risk

- Ensure consistent use of the Framework across organisations and sectors.

The MARAM Framework outlines:

- An approach to practice which is underpinned by the Framework Principles

- Four conceptual ‘pillars’ for organisations to align their policies, procedures, practice guidelines and tools.

- Information to support a shared understanding of the experience of risk and its impact on individuals, families and communities.

- Expectations of practice that are underpinned by a shared understanding of the range of roles across the service system, and consistent and collaborative practice.

- An expansion of the range of organisations and sectors who will have a formal role in family violence risk assessment and risk management practice.

A summary of these elements is described in the Foundation Knowledge Guide (below) to provide background for individual professionals and services.

This document contains the MARAM Practice Guides which underpin the MARAM Framework. These resources are provided in three volumes and are designed for use by professionals and organisational leaders:

- The Foundation Knowledge Guide which focuses on the legislative context, roles and interactions with the service system, risk factors, key concepts for practice and presentations of risk across different age groups and Aboriginal and diverse communities. The Foundation Knowledge Guide is required reading for all professionals across leadership and governance, management and supervision to direct practice roles. Professionals should be familiar with this introductory and supporting information prior to engaging with the MARAM Responsibilities for Practice Guide

- The Responsibilities for Practice Guide reflects each of the ten responsibilities of practice set out in the MARAM Framework. This guide focuses on how to apply foundation knowledge and then build on this to provide practice guidance from safe engagement, identification of risk, through levels of risk assessment and management, secondary consultation and referral, information sharing, and multi-agency and coordinated practice. Professionals’ responsibilities will vary based on the nature of their role within a service or organisation and will be informed by the contact they may have with victim survivors and perpetrators. Professionals should work with their organisational leaders to understand their role and to identify which responsibilities they should be applying in practice. Professionals are required to be familiar with each of the responsibilities that are a part of their role

- The Organisational embedding guide supports organisational leaders to effectively support professionals and services to undertake their roles and responsibilities. This will link the work undertaken by professionals and services to the alignment of organisations’ policies, procedures, practice guidance and tools under the MARAM Framework. Professionals in leadership or management roles should be familiar with the Organisational embedding guide. In addition to responding to the requirements for alignment under the MARAM Framework, organisational leaders should assist professionals and services within their organisations to identify and use the practice guides appropriate to their roles.

All MARAM tools and practice guides were developed through extensive consultation with a range of stakeholders including experts, departmental policy and practice areas, and professionals in specialist and universal services, including those specialising in working with Aboriginal communities, diverse communities, children, young people and older people. The guides will continue to be updated and evaluated to reflect the evolving evidence- base relating to experiences of family violence across the community and shifting practice directions that will contribute to this evidence base.

Responsibility 1: Respectful, sensitive and safe engagement

Responsibility 1 of the Family Violence Multi Agency Risk Assessment and Management Framework: Practice Guides.

Download and print the PDF or read the accessible version:

1. Respectful, sensitive and safe engagement

1.1 Overview

This guide should be used to create a respectful, sensitive and safe environment for people who may be experiencing family violence. This includes an emphasis on listening to, partnering with and believing victim survivors as experts in their own experience.

This guide may be used where family violence is already suspected or not and is vital to support disclosure and facilitate identification and screening, which are discussed in Responsibility 2.

Your organisation will have its own policies, practices and procedures relevant to safe engagement. Leaders in your organisation should support you and others to understand and implement these policies, practices and procedures.

Key capabilities

All professionals should use Responsibility 1, which includes understanding:

- The gendered nature and dynamics of family violence (covered in the Foundation Knowledge Guide and the MARAM Framework).

- Respectful, sensitive and safe engagement as part of Structured Professional Judgement.

- How to facilitate an accessible, culturally responsive environment for safe disclosure of information.

- How to respond to disclosures sensitively and prioritise the safety of victim survivors.

- How to tailor engagement with adults, children and young people, including Aboriginal people and people from diverse communities.

- The importance of using a person-centred approach.

- Recognising and addressing barriers that impact a person’s support and safety options.

All information in this guide is relevant for assessing risk to any adult, child or young person who is a victim survivor.

There are additional practice considerations on safe engagement with children and young people in Section 1.10–1.12 of this guide.

Information which refers to a perpetrator in this guide is relevant if an adolescent is using family violence for the purposes of risk assessment with a victim survivor about their experience and the impact of violence. Risk assessment and management for adolescents should always consider their age, developmental stage and individual circumstances, and include therapeutic responses as required.

Remember

The practice guidance across all ten practice responsibilities builds on the Foundation Knowledge Guide which covers the gendered nature and dynamics of family violence, and its impacts. The Foundation Knowledge Guide includes information on practice approaches which complement the information in this guide, including trauma- informed, person-centred practice, applying an intersectional lens, reflective practice and identifying and addressing bias.

1.2 Engagement as part of structure professional judgement

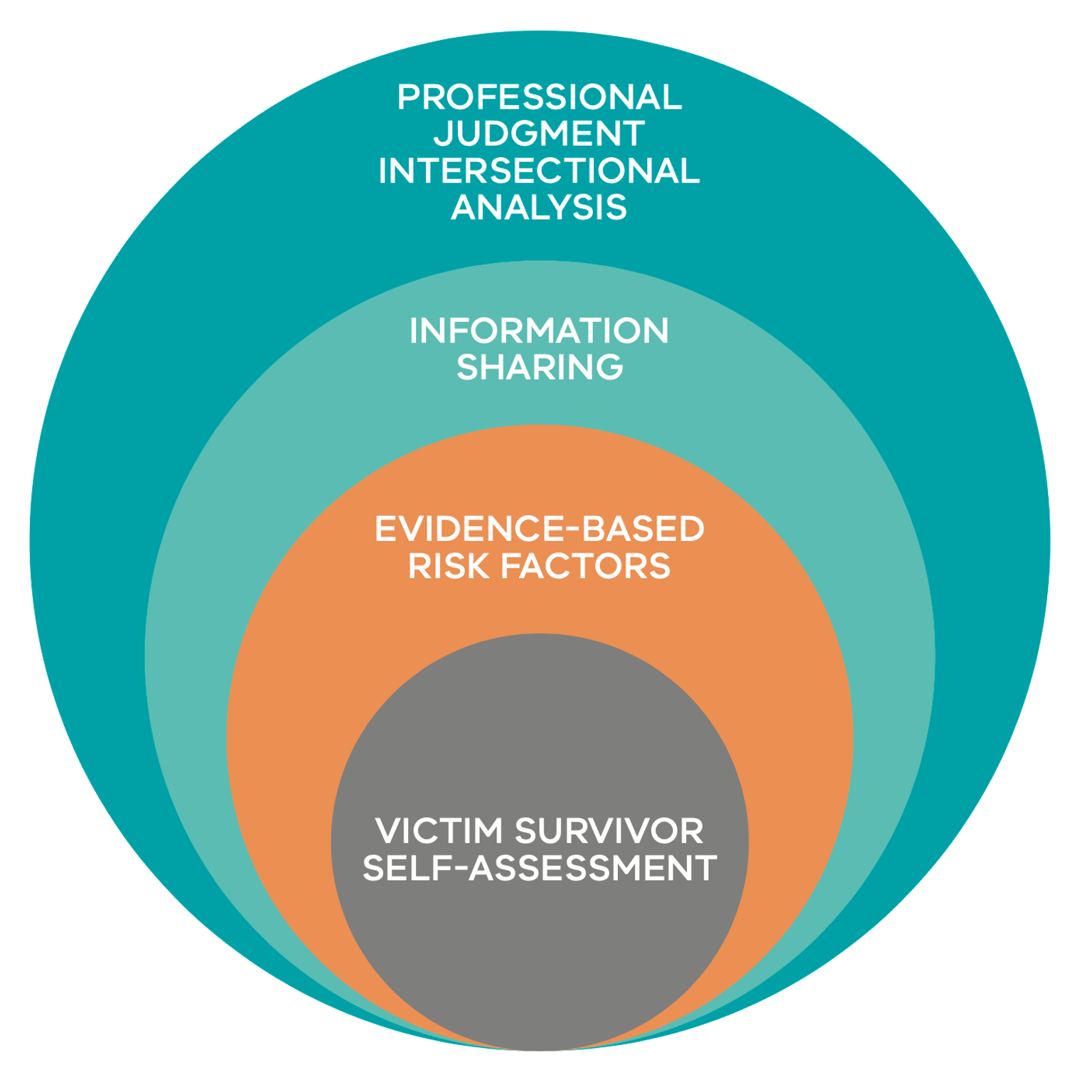

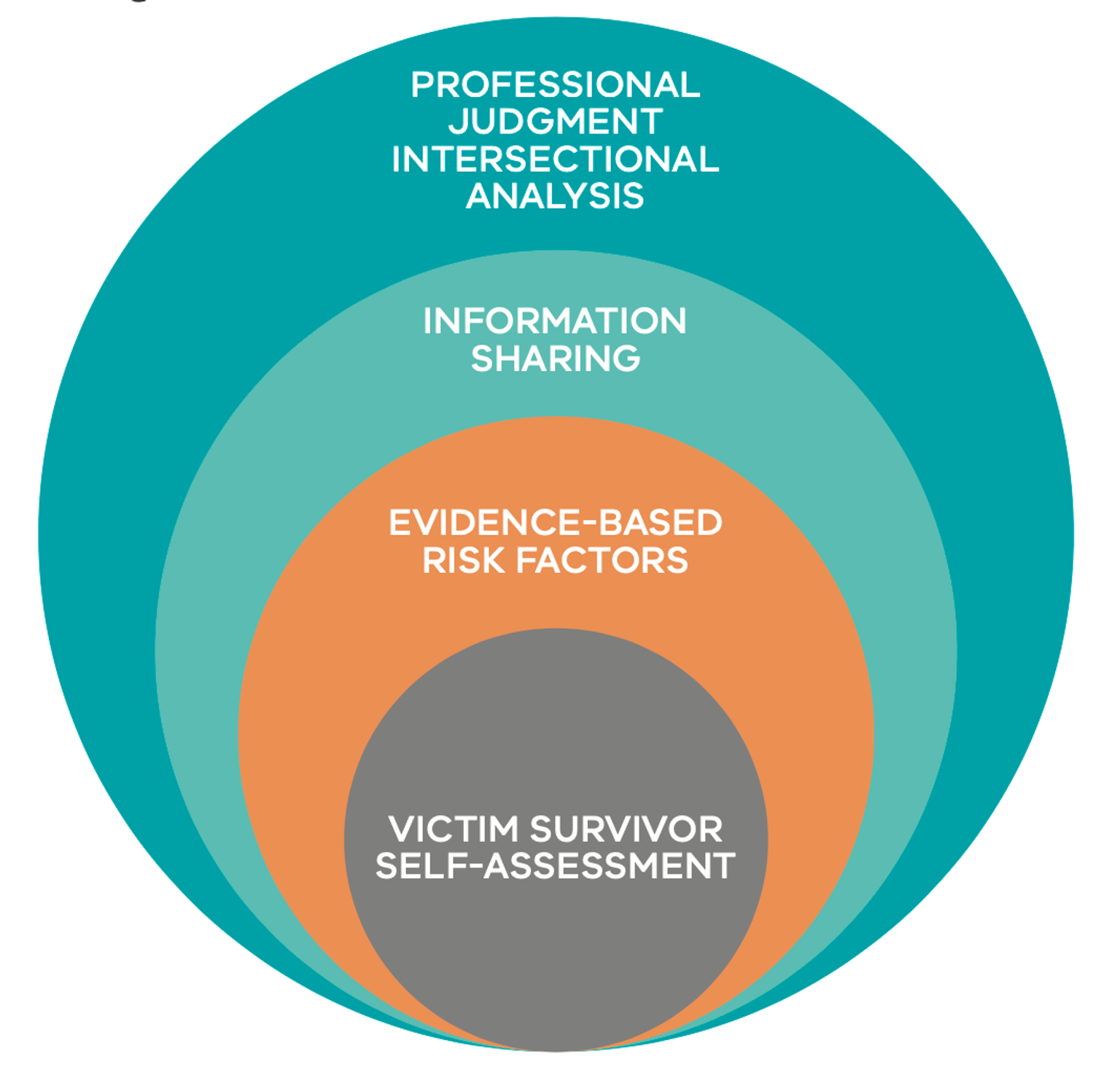

Reflect on the model of Structured Professional Judgement outlined in Section 9.1 of the Foundation Knowledge Guide.

Respectful, sensitive and safe engagement is an important foundation that supports Structured Professional Judgement. This practice creates the trust and rapport with a victim survivor to create an environment where they can feel safe and respected to talk about their experiences of family violence. This underpins the key element of Structured Professional Judgement — facilitating a victim survivor to disclose their self-assessment of their fear, risk and safety, by letting them know they will be believed and supported.

Creating a safe and supportive environment will allow victim survivors to feel believed when they are asked to disclose their self- assessment of fear, risk and safety and whether they hold concerns for other family members’ safety. An adult’s self-assessment of their own level of family violence risk is a strong indicator of the level of risk (see Responsibility 2).

Further information about Structured Professional Judgement will be provided in each of the relevant chapters of the Responsibilities for Practice Guide.

1.3 Creating a safe environment to ask about family violence

Key steps to creating an environment where the person feels safe and respected to talk about their experiences of family violence include considering:

- The immediate health and safety needs of each person (adult or child) who may be experiencing family violence.

- The physical environment, including accessibility

- Communicating effectively, and

- Safely and respectfully responding to the individual’s culture and identity.

1.3.1 Prioritising immediate health and safety

As a first priority, determine if there is an immediate threat to a person’s health or safety. If yes, contact:

- the police or ambulance by calling 000, and/or

- other emergency or crisis services for assistance.

Assessing immediate safety includes both:

- Identifying that a threat is present. This might include situations where the perpetrator is able to access the victim survivor and has made a specific threat or where the specific location of the perpetrator is unknown.

- Determining the likelihood and consequence if immediate action is not taken to lessen or prevent that threat. It may also include facilitating or encouraging access to medical treatment (where physical and sexual violence has occurred).

Further guidance on determining immediate risk to safety from family violence is outlined in Responsibility 2.

Your service or organisation should have established policies and processes in place to manage an immediate threat. If an immediate threat is identified and the whereabouts of the perpetrator is unknown, your service’s safety arrangements could include:

- Conducting interviews in a secure physical environment (see Section 1.3.2), arranging care for children or young people for this to occur, if they are present

- Using the prompting questions and commencing use of the Screening and Identification Tool (Responsibility 2, Appendix 3) or a risk assessment tool to establish the presence of family violence if observable signs of trauma or risk are present (Responsibility 2, Appendix 1)

- Making security or other suitable personnel to be available to prevent the perpetrator entering the premises, and/ or relocating the victim survivor to a safer environment

- If there is an immediate threat, follow your workplace policies and procedures and take any actions necessary, including calling the police.

It may not be appropriate, safe or reasonable to undertake a further risk assessment until any immediate safety risks or health needs are addressed.

1.3.2 Physical environment

The physical environment sets the context for building rapport with the victim survivor

- Make the person feel safe and ask about the things they need to feel comfortable

- Create a safe space — for example, provide physical cues that the client is welcome, and that their culture and other identities will be respected (see Section 1.4 and the Foundation Knowledge Guide).

It is critical that you do not ask questions in the presence of a perpetrator, alleged perpetrator, or adolescent who may be using family violence. Doing so may increase the risk to the victim survivor and any child victim survivors in their care. Using a private environment when asking about sensitive and personal information is critical to establishing rapport with the victim survivor.

If the person suspected of using violence is present, your organisation should have policies and procedures for safely separating them from the victim survivor to provide a private space for conversation. For example, you might ask the person who may be using violence to go to another room by:

- Stating that it is your agency’s standard practice or policy to ask questions in private, or

- You might ask them to complete administration forms.

If the person suspected of using violence is a carer, you may need to arrange alternative communication or support assistance to enable the victim survivor to take part in a safe conversation.

If it is not possible to separate the victim survivor and perpetrator or alleged perpetrator you should consider deferring the conversation about family violence until a safe environment can be established. You may need to consider options on how to re- engage with the victim survivor at another time to support this conversation, such as by booking a follow-up appointment.

When adolescents use family violence against a parent, carer, sibling or other family member, a parent or carer may wish to be engaged in the service along with the adolescent. You should seek the victim survivor’s views and prioritise their safety when considering how to engage in these situations. Keep in mind that adolescents who use violence may also be currently experiencing or have experienced past family violence. Adolescents should always be provided with support that considers their age and developmental stage and circumstances, and be considered for therapeutic responses. Further information on working with adolescents who use family violence is in Responsibility 7 and in the Foundation Knowledge Guide at Section 11.2.

1.3.3 Communication

Creating a safe environment means actively listening with empathy and without judgement. Validate the information provided by showing you believe the victim survivor and are seeking to understand their experience, so you can work together to find ways to help.

As a basis for building a relationship of trust, you should provide key information for example, about what you/your service is there to provide, and clearly set expectations. Always consider the communication needs of any child or young person who is a victim survivor, seeking their views as appropriate, safe and reasonable and validating their unique experiences.

As a priority, ensure that the person can communicate with you. You should consider and make efforts to address any barriers to communication, including those relating to English language proficiency, or for people with disabilities requiring communication adjustments or supports. For example, ensure that you:

- Engage in a culturally sensitive and respectful manner — for example, you could ask if they would like support from a bi-cultural or bilingual worker or services from an Aboriginal organisation. You should adjust to the level of engagement that is comfortable to the person. For example, eye contact is desirable in many cultures and for many people but not all. Consider how the person is engaging with you and be aware that reluctance to make eye contact is not a sign of evasiveness. You should give the person the opportunity to voice their preference regarding the gender of the worker they are engaging with

- Arrange access to an accredited interpreter if needed (level three if possible) or an Auslan interpreter for people who are deaf or hard of hearing. For some communities with smaller populations, it is more likely an interpreter may know the victim or perpetrator. You can avoid identifying names or use an interstate interpreter. Offer an interpreter of the same gender as them. Children, family members and non-professional interpreters should not be used

- Ensure access to any necessary communication adjustments or aids if the person has a disability affecting their communication or other communication barriers, and confirm that they understand the information provided to them (see Practice Tip, below)

- Individually acknowledge the experiences of children and young people who may be victim survivors, particularly if they are present. If developmentally and age appropriate, provide the opportunity for them to raise any concerns of their own. Introduce yourself and explain that you need to speak with their parent/carer in private. Provide an appropriate and safe place to wait, and give them permission to come back into the room if they need anything

- You can assess risk directly with children if it is safe, appropriate and reasonable to do so. If you are doing so, consider if a parent/carer who is not using violence, or another safe person, should be present. If a parent/carer is present, be aware this may affect the responses the child or young person provides. Ensure that questions you ask are appropriate for that child or young person’s developmental age and stage (discussed further below)

- Let the person know that they can take a break at any time, and schedule breaks as required, especially if the person is distressed, ill or has a cognitive impairment or other relevant disability and remind them of this at appropriate intervals

- Ask the person if they would like to have an advocate or support person present (see Section 1.7). Do not assume this if another person attended with the victim survivor. Check that the advocate/ support person is not using violence or is close to the suspected perpetrator. Where possible, ask the question in private.

Practice tip

If the adult, child or young person has a disability or developmental delay that affects their communication or cognition, seek their advice or the advice of a relevant professional regarding what adjustments might assist (including any augmented or alternative communication support, such as equipment or communication aids).

If the victim survivor has an existing augmentation or alternative communication support plan in place, you should engage directly with them, with support from a support worker, advocate or other communication expert, if required, to help you navigate its use.

In cases where a child’s carer or primary caregiver is not a perpetrator or suspected/ alleged perpetrator, you can consult with them.

Where there is an existing relationship between the victim survivor and an advocate or support person, consider this relationship before agreeing to the inclusion of the other professional.

If the person suspected of using violence is a person who usually provides communication support, arrange alternative communication or support assistance to enable the victim survivor to take part in a safe conversation1.

Communicating about a perpetrator’s use of violence

Where family violence is identified or suspected, effective communication also includes placing responsibility for the violence and its impacts with the perpetrator. If an adolescent is using violence, placing responsibility should also occur with an understanding of their age, developmental stage, individual circumstances and family context. For example, any developmental delay or their own experience of family violence. This includes in situations where an adolescent is using family violence toward a parent/ carer, sibling, other family member or intimate partner.

Perpetrators often lead victim survivors to believe that the victim survivor caused or provoked the violence because they did not do something ‘right’. Perpetrators use this narrative to excuse their violence. It is important to keep the focus on the perpetrator’s responsibility for the violence, even if the victim survivor blames themselves.

1.3.4 Cultural safety and respect (using intersectional analysis in practice)

Reflect on information provided in the Foundation Knowledge Guide and the MARAM Framework on using an intersectional lens. The Foundation Knowledge Guide also includes more information on recognising personal bias and understanding the experience, structural inequality and barriers experienced by Aboriginal people and people from diverse communities or at-risk age groups.

Cultural safety is about creating and maintaining an environment where all people are treated in a culturally safe and respectful manner2. All people have a right to receive a culturally safe and respectful service, including:

-

Where there is no challenge or denial of a person’s identity and experience

-

Showingrespect,listening,learning,and carrying out practice in collaboration, with regard for another’s culture whilst being mindful of one’s own potential biases

-

Undertaking genuine and ongoing professional self-reflection about your own biases and assumptions including with more experienced professionals

-

Listening and understanding without judgement.

Other practical steps you can take include:

-

Be familiar with and know the requirements of your organisation’s client access and equity policies and procedures

-

Ensure a welcoming environment with inclusive signage and posters — for example, an Aboriginal flag, rainbow flag or transgender and gender diverse flag

-

Prior to meeting the person, ensure you know their name, including those of any accompanying children. Identify and review notes if available

-

Identify and challenge your own biases (see Foundation Knowledge Guide Section 9.7).

Providing a culturally safe response, particularly for Aboriginal people, includes respecting an individual’s right to self- determination. Consistent with a person- centred approach (described in detail in Foundation Knowledge Guide at Section 9.3), cultural safety includes recognising a victim survivor as the expert in their own experience and including and supporting them to make decisions about their own risk management.

Providing a culturally safe response also involves understanding how family violence is defined in different communities, including for Aboriginal communities. Further information is outlined in the MARAM Framework and Foundation Knowledge Guide at Section 10.4. Assessment processes must be respectful and inclusive of broad definitions of family and culture. For example, it is particularly important not to assume who is ‘family’ or ‘community’ to a child or young person, but rather to ask who should be involved in risk assessment and management.

1.4 Asking about identity

Always enquire about and record the language, culture and other aspects of identity of each family member.

Never assume you know these, or that they will be the same for each family member. It is good practice to openly acknowledge the culture a person identifies with in a positive and welcoming way. This includes, for example, ensuring Aboriginal children or young people that may be in the family are identified, even when accompanied by a non-Aboriginal parent/carer. Information about a person’s identity must inform all subsequent assessment and management responses.

Until you have built trust and rapport, some people may choose not to disclose their identity groups. This might be for a range of reasons, including fear of discrimination based on past experience.

For Aboriginal people, structural inequality, discrimination, the effects of colonisation and dispossession, and past and present policies and practices, have resulted in a deep mistrust of people who offer services based on concepts of protection or best interest. Professionals should be mindful of how this might affect a person’s actions, perceptions and engagement with the service. Acknowledge the impact these experiences may have had on a person, their family or community. Assure the person that you will work with and be guided by them to provide an inclusive service and minimise future discriminatory impacts through their engagement with your service.

It is also important to recognise the strength and resilience of Aboriginal people and culture in the face of these barriers and structural inequalities. Kinship systems and connection to spiritual traditions, ancestry and country are all important strengths and protective factors. The role of family is critical and Aboriginal children are more likely than non-Aboriginal children to be supported by an extended, often close family. Assessment of Aboriginal children must support cultural safety and take into account the risk of loss of culture.

You can find more information about cultural safety, including for Aboriginal children, and Aboriginal identity and experience in the Foundation Knowledge Guide at Section 10.4.

Why do some victim survivors not report family violence?

Victim survivors, predominantly women and children, might not report their experience of family violence or it might be reported in a way that obscures its nature or extent. For example, by reporting an injury, but not attributing it to violence (sometimes called ‘hidden reporting’).

Many varied and complex factors lie beneath hidden reporting and under-reporting, including shame, fear and stigma. Victim survivors may not recognise certain behaviours — particularly emotional or economic abuse — as constituting family violence.

Many women might not disclose or might minimise the extent of violence in an effort to manage the perpetrator. For example, a woman might fear that if she discloses the violence, the risk to herself or her children will escalate.

In the case of adolescent family violence, parents/caregivers may feel stigma and shame arising from unfair assumptions about the victim’s ability (often the mother) to be a good parent and the shock that their child (or grandchild or sibling) has used violence against them. Shame is exacerbated by lack of community awareness about this form of violence. Parents/carers might also fear their child may get a criminal record if the violence is reported to police.

Women may find sexual violence particularly difficult to disclose. The Royal Commission into Family Violence reiterated that sexual abuse is often ‘left under the table’ because of the additional layers of shame.

Responsibility 2, Section 2.6 describes a range of reasons a person may be reluctant to disclose family violence, and how you can address barriers to disclosure.

People who have diverse individual and/or social identities, circumstances or attributes, may or may not choose to disclose that to a professional unless they trust the professional and feel a rapport. You can support disclosure by never assuming how the person and their partner or parents identify. For example:

-

Don’t assume gender identity (which can result in misgendering) based on a person’s voice, appearance or how they dress as this can lead to disengagement

-

You can ask what pronouns a person uses by saying “I use [she and her / he and him / they and them] pronouns, what do you use?” This can let the person know you can provide inclusive and respectful service

-

You can ask if a person identifies as LGBTIQ and if there is a way you can support them to engage with your service, or if there are external supports available to ensure they are comfortable engaging with you

-

You can ask if the person has any disabilities, developmental delays or mental health issues, and if there are any supports or adjustments you need to make.

Services should be aware that identity is complex and that aspects of a person’s identity should be considered as part of their whole experience. To help inform your response, you might choose to engage in secondary consultation with specialist family violence services with an expert knowledge of a particular diverse community, and the responses required to address the unique needs and barriers faced by this group (see Responsibilities 5 and 6).

1.5 Building rapport and trust

From the first moment of engagement, victim survivors will be making decisions about how much information to disclose.

Building rapport with victim survivors is crucial as people are more likely to disclose the full extent of the violence if they feel they will be believed, not judged and provided with support.

When strong rapport and engagement have been established, victim survivors are more likely to discuss their experience, including the circumstances, relationships, impacts of violence and their self-assessment of their own fear, risk and safety.

Professionals will often have built rapport before family violence has been identified or disclosed. For this reason, people will often choose to disclose to a person in a service that they have existing rapport with. It is critical that all professionals are able to provide an appropriate response that preserves rapport and facilitates continued engagement and referral.

Building rapport and trust to support engagement is the responsibility of all professionals. Key elements of rapport building include:

- Fully explaining your role and responsibility within an organisation and introducing the risk screening or assessment process (as applicable) in a sensitive way. This should include an outline of the assessment process

- State that screening and assessing risk, as applicable, is a regular part of your service/organisation’s engagement. State that risk is dynamic and can change over time, so this conversation is undertaken regularly to understand if risk has changed or escalated. It is important to specifically address safety on each occasion. For example, to remind the person to call 000 in an emergency and that 24-hour services are available to support them

- Provide adequate information so the person can make informed choices. This includes providing information about information sharing laws which allow for the sharing of relevant information without consent in specific circumstances, discussed further in Responsibility 6

- Provide advice on your legal obligations as a professional, as applicable

- Ask open-ended questions about wellbeing to start the conversation.This might include questions about the person’s circumstances, identity and their relationship (including positive aspects) before moving to more specific and detailed questions about any family violence they may be experiencing

- Acknowledge the courage it has taken for the person to talk about their experiences with you and that you recognise them as the expert in their own experiences, circumstances and the violence they may have endured

- Continue to affirm to the person that they and their children (if applicable) have a right to live free from violence and that there are services and options, including legal options, to support their safety

- Be aware of how the person has expressed their identity or situation (for example, do they identify as Aboriginal, identify with a particular communityor faith groups, or as a person with a disability). Understanding a person’s identity can help you understand how their experience of family violence relates to other experiences of structural inequality, barriers to service access or discrimination, and its particular impacts on them (see Foundation Knowledge Guide Section 9.4)

- Highlight that any possible interventions will be guided by the person’s views and wishes

- However,safetyforthemselvesandany children that may be experiencing violence will be prioritised. Remember that when any victim survivor’s safety (adultor child) is in competition with an adult’s choices, safety is the paramount concern

- Be transparent around how information they disclose may be shared with other professionals or services, including Child Protection

- Tailor your communication, be flexible and not overly prescriptive in how you ask questions. This can include allowing people to tell their story as a way of gathering relevant information. Hearing a person’s story, guided by your questions and a conversational style can help to draw out information without seeming like an interview.

1.6 Trauma-informed practice in a person-centred approach

Refer to the Foundation Knowledge Guide on information about intersectionality, trauma-informed and person-centred practice. By combining intersectionality and trauma- informed practice into a person-centred approach, it will make it possible for a victim survivor to be validated and aware of the ongoing impacts of their experiences, and how you can tailor your responses to empower them to make informed choices and access services and supports.

You may be engaging with a victim survivor who you know has experienced trauma, from family violence and/or another cause. You can seek secondary consultation or seek shared support from a professional with trauma-informed practice expertise, such as specialist family violence service, to assist you. Their expertise may support you in engagement, and also assist you in a fuller consideration of family violence risk, experiences and management strategies.

Some of these professionals may also have expertise in, for example, art or music therapy, which may support your engagement and give you access to the information you need in a different way. This may be of use in engaging with someone with limited verbal capability.

1.7 Using an advocate or support person

You should ask the victim survivor if they need or would like a support person in the initial engagement process and revisit this during the assessment or management stages as required. The advocate/support person could be a trusted friend or family member who is not a perpetrator (such as a parent/ carer), or a relevant professional, as appropriate.

A support person should be appropriate and safe. There must be no coercion or control from the advocate/support person towards the victim survivor. A perpetrator may use their presence to intimidate or coerce a victim survivor, controlling the information they share as well as behaviour, such as by answering questions on their behalf or reducing the victim survivor’s access to interventions to support their safety.

You should have a private conversation with the victim survivor prior to an assessment, to explore their relationship to their identified advocate/support person. You should ask if the victim survivor feels comfortable with their advocate/support person knowing intimate and personal details about their life, or whether their presence will limit or change what a victim survivor will say.

If an advocate or support person is a new partner, be aware that a victim survivor may defer to a new partner or edit their story in their presence. A victim survivor may seek or need you to deny the support person access if they do not feel comfortable challenging their presence.

If a victim survivor has a cognitive impairment or requires communication adjustments, it is important to work on the assumption that the person has capacity and to overcome any communication barriers. Talking with the person directly rather than through their nominated advocate, support person or carer will assist to build trust and rapport and support disclosure. If required, you can consult with the Office of the Public Advocate for further advice.

1.8 Different factors that impact support and safety options

There are many different factors that might affect a victim survivor’s access to support and safety options.

These factors may also impact on the approach you take to create safe engagement. You should be familiar with how discrimination, structural inequality and barriers have affected Aboriginal people and people who identify as belonging to a diverse community or people from at-risk age cohorts (see Foundation Knowledge Guide Section 9.4).

People may have experienced racism, sexism, ableism, ageism, homophobia or transphobia, or judgement about their personal traits or circumstances. As a professional, it is important for you to acknowledge the influence of both your own culture and values, your biases, and those of the broader service system. Recognising these can enable you to challenge and address them and help you build awareness of your own place in the service system’s creation of structural privilege and power.

You should demonstrate an open and respectful approach to cultural and experiential differences. Consider how your engagement approach, as well as assessment and management practice can be tailored to reduce or remove barriers to engagement for people who face structural inequality and discrimination. Inclusive practice can be informed by asking the person, “What can I do to support you in our service?”.

You can find detailed information about how these different factors intersect, recognising structural inequality and discrimination, and engaging in person- centre reflective practice in the Foundation Knowledge Guide.

1.9 Responding when you suspect a service user is using family violence

As a professional, from time to time you will come into contact with people, including adolescents, who you suspect may be using family violence.

Use of family violence may be indicated from the person’s words or actions, or through another source of information.

A perpetrator or adolescent using family violence may use tactics to try and align you to their position to justify, minimise or excuse their use of violence or coercive behaviour, or to present themselves as a victim survivor. This is known as collusion and these behaviours are outlined in the Foundation Knowledge Guide at Section 11.

Identifying who is perpetrating family violence can be complex. Guidance on understanding misidentification of victim survivors and perpetrators, and identifying predominant aggressors is outlined in the Foundation Knowledge Guide at Section 11.3 as well as in Responsibilities 3 and 7.

You should not engage with a person directly about family violence if you suspect they are perpetrating family violence, unless you are trained or required to do so to deliver your service. This is because confrontation and intervention may increase risk for the victim survivor.

Instead, you should consider proactively sharing information, as authorised, with a specialist family violence service that can support the person you suspect is experiencing family violence (see Responsibility 5 and 6). You can also contact a specialist family violence service with expertise in assessing perpetrator risk and who can safely communicate with a person who may be using violence to engage them with appropriate interventions and services, such as behaviour change programs.

The age and developmental stage of adolescents who may be using violence, their circumstances, experience of trauma, emotional state, mental health and other contexts will inform the assessment or management response. Therapeutic responses, including those that involve other family members, particularly the non-violent parent/carers should be considered (see Responsibility 3). Some responses to adolescents (for example, those who have experienced trauma or have a developmental disability) will include behaviour modification and a skills-based approach.

A trauma-informed and developmentally appropriate approach to engaging with an adolescent who uses family violence may be used if their behaviour stems from trauma and learned violent behaviours from their parent/carer, or they are using intimate partner violence (noting that sometimes a young person may be using violence in both family and intimate partner contexts).

Further information about responding to adolescent family violence is in Responsibility 7 and in the Foundation Knowledge Guide at Section 11.2.

Respectful, sensitive and safe engagement - children and young people

Note: The prevalence of family violence against women and children, and against women as mothers and carers, is well established and recognised across the service system. Recognising this, the following section on risk to children uses gendered language to describe experiences for mothers, including damage to the mother/child bond caused by perpetrator behaviours. However, it should be noted that this guidance also applies to all forms of families and parenting.

Language in this section of ‘mother/carer’ refers to a parent/carer who is not using violence (a perpetrator).

1.10 Experience and engagement

How information in each of the preceding sections (Sections 1.1–1.9) applies to children and young people should also be considered.

A child is defined as a person under the age of 18 and a young person is aged 12–25 years. The guidance below is relevant for children and young people up to the age of 18. You should determine, using your professional judgement, if a young person who is approaching adulthood should be engaged using adult-centred guidance, as detailed above.

It is important to view and acknowledge children and young people as victim survivors in their own right:

- The risks to children and young people can be different to those of an adult victim survivor and may be different for each child or young person.

- Children and young people may be victim survivors of family violence whether they are targeted or not, or directly exposed or not, even if they do not hear or see it. Children who are exposed to family violence or its impacts are more at risk of direct family violence, including physical or sexual abuse.

- Children who experience family violence from an adolescent, such as an adolescent sibling, may be impacted in the same ways as children who are impacted by family violence from an adult. This includes being at risk of physical or sexual abuse.

- Professionals should recognise the experience of violence on a child or young person, including trauma and cumulative harm which can disrupt children’s achievement of development.

- Family violence can create significant risks to a child or young person’s social, emotional, psychological and physical health and wellbeing. Impacts on children who live with family violence may be acute and chronic, immediate and cumulative, direct and indirect, seen and unseen.

- Professionals should provide opportunities for children and young people to raise any views, wishes and concerns they have, and contribute to risk assessment, management and safety planning.

Recognising the signs of family violence or its impacts can be difficult. It is important to remain aware of and balance your own biases and ensure you are being non-judgemental when considering the experiences, wellbeing and safety of children and young people. For example:

- Parents/carers are expected to set boundaries that are appropriate to age and developmental stage for children and young people and these vary across and within all cultural and faith groups, as do approaches to teaching and discipline.

- Male and female children/young people, and children who are non-biological children of one or both parents, may be treated differently within families and according to family, cultural and other gendered norms.

In addition to barriers to service access arising from discrimination and structural inequality related to identity (as outlined in the Foundation Knowledge Guide) children and young people may experience additional barriers due to their age and developmental stage. This includes, generally, requiring consent to engage with services from a parent/carer. You should note that consent is not required to assess or manage family violence risk or promote wellbeing or safety of children and young people.

Each child or young person experiences family violence differently, and in particular forms of violence, to other family members depending on their age, stage of development, identity, their relationship to the perpetrator, and their level of dependence on adult carers. For example, as outlined in the MARAM Framework:

- Aboriginal children experience higher rates of family violence, including from non-Aboriginal family members.

- Girls with disabilities are twice as likely to experience family violence.

- Young people from LGBTIQ communities may experience forms of violence relating to ‘coming out’, their gender identity, and rejection from their families, and are over-represented in homelessness populations.

Children and young people engaged in universal services, such as early years services or education, are likely to have their initial risk identified without a parent/carer present:

- This should only occur if it is safe, appropriate and reasonable to do so.

- In some cases, professionals should seek the input of a parent/carer who is not using violence for further risk assessment.

- Where risk is present for children and young people, the parent/carer should also have their risk assessed.

Young people can be affected by family violence in their own intimate relationships, such as their ‘dating relationships’. Although young women experience family violence at higher rates than their older counterparts, they can also be reluctant or unable to identify the behaviour as coercive or abusive.

Young women experiencing family violence are more likely to disclose or seek help from a peer, and peers are also more likely to know about violence or coercion within a relationship. Therefore, disclosures may not be made directly from the young person experiencing the violence to a professional or service. In such cases, support also needs to be provided to peers who have received a disclosure from a friend.

Many adolescents experiencing family violence are likely to enter the service system through youth support, youth justice or homelessness services.

Adolescents who may be using family violence, may be currently experiencing or may have experienced family violence, sexual assault or abuse in the past. Some adolescents may use violence due to difficulty with emotional regulation or heightened emotional states. This can be further exacerbated by substance use, particularly substances like methamphetamine. Any responses to adolescents should be underpinned by an understanding of the context in which the use of violence occurs, and therapeutic responses and/or behaviour modification strategies should also be explored (see Responsibilities 3 and 7).

1.10.1 How can you support assessment of a child or young person’s risk?

Children and young people, like adult victim survivors, hold information about their own experience of risk. Child victim survivors should be supported through direct engagement where appropriate, safe and reasonable to do so. Engaging directly with children and young people can help them to feel safe.

Most older children and young people can understand and articulate their experiences of violence and coercive control, and this experience differs from those of adults.

While acknowledging children’s unique and individual needs, many children may prefer to be spoken to with the support of their parent/carer who is not using violence, or other significant person/carer. If age and stage appropriate they should have the opportunity to speak privately if they wish to do so.

There are a range of options for assessing a child or young person’s risk. This may occur by:

- Asking questions directly if appropriate, safe and reasonable to do so (reflecting their age, developmental stage and individual circumstances).

- Asking questions of the parent/carer who is not a perpetrator (usually a mother, who may also be a victim survivor).

- Asking questions of another appropriate adult or professional engaged with the child.

You should consider each option as to whether it is safe, appropriate or reasonable. Further guidance on determining the appropriate approach to assessing risk for children and young people is in Responsibility 3.

Each option requires you to ensure you have built rapport with any supporting, non-violent parent/carers and the child or young person.

1.11 Building rapport with parent/carer to support assessment of a child or young person

Remember

Victim survivors who are parents/carers (usually mothers) may prioritise immediate action that minimises harm to themselves and their children. It should be acknowledged that victim survivors who seek assistance and intervention are acting in the best interests of the child or young person.

Mothers who may also be victim survivors are often a key source of information and expert in assessing risk to self and their children. However, in some situations, their ability may be restricted in providing for their child’s needs due to the actions of the perpetrator. Due to their own experience of violence from a perpetrator, their assessment of risk and impact of the violence on their children should be balanced with an independent assessment of the child or young person’s risk. Parents/carers may require information and support to understand the assessment of risk for their children.

A perpetrator’s actions and behaviours may be specifically directed to undermine a child’s relationship with their parent/carer (usually the mother). Children who witness or experience family violence directly, or are exposed to its impacts, may not recognise protective behaviours from a parent/ carer who is not a perpetrator, or might be accustomed to hiding or tolerating the violence.

Mothers might need assistance to help their children make sense of their negative experiences within the family home. It is important to recognise that parents/ carers often go to significant lengths to try to minimise or prevent the perpetrator’s violence from impacting his children. Sometimes these actions have their own impact on the child’s safety, and on their relationship with their mother.

Perpetrators often use family violence to attack or undermine the child’s bond with an adult victim survivor/other parent/ carer (described in detail in the Foundation Knowledge Guide at Section 10.2) It is important to create a safe environment to explore risk that is being experienced by children, including through talking and building rapport with a parent/carer (who is not a perpetrator) and may be a victim survivor. Approaches to do this include:

- Asking the parent/carer rapport-building questions about the children in the family. For example, “tell me about your children”. It is important to establish early on the level of risk that a child is experiencing, and this should be considered independently to any risk being experienced by their parent/carer

- Assessing the risk of adult victim survivors without children present. Arrangements should be made for appropriate professionals, or another safe person, to care for the children during this time.

- Asking specific questions about what risk the perpetrator poses to the children (such as through screening or assessment, see Responsibilities 3 and 7), and how the violence is impacting the children. This should be done whether or not the violence is being experienced by direct actions towards a child or indirectly through exposure to violence or its impacts. Affirm the experience and impact of indirect violence on a child.

If you can’t assess children directly, you can build rapport and trust with the parent/ carer through their assessment to help you do so in the future. This will help to reduce the fear, shame and self-blame that a parent/carer may feel if their child has experienced family violence. A good rapport can also support direct discussion if the parent/carer has fears about possible engagement with Child Protection, and is unsure how they can be supported in this process. This is particularly important when working with adults, children or young people who identify as Aboriginal, belonging to a diverse community group and older people who may have experienced discrimination, impacts of child removal or other structural inequality and barriers which have created mistrust in services (see also the Foundation Knowledge Guide).

1.12 Building rapport to engage directly with children and young people

If you are trained and resourced, or your role is to engage with children and young people, you can do so for the purposes of assessing risk. If not, consider engaging or seeking secondary consultation with services that specialise in working with children and providing therapeutic interventions. Consider:

-

If a child is old enough to speak with you, talk to them about your role as appropriate to their age and developmental stage. For example, you might say to a very young child “I am here to help you and mummy.” You should tailor your use of language and style to meet the needs of the child or young person.

-

If a child or young person has experienced trauma, ensure your practice does not further traumatise them. As described above, consider seeking secondary consultation or support from appropriate professionals or services (see Responsibility 5 and 6).

-

The older and more developmentally advanced a young person is, the more information you can/should be able to provide. If a young person is nearer in age to adulthood (18 years), you can consider if it is age and developmentally appropriate to use the adult risk assessment tools, discussed further in Responsibility 3.

-

Your assessment will be more accurate and complete if children and young people have direct input. For example, you might note the presence of a range of potentially supportive adults in a child’s life. However, the child/young person themselves is best placed to tell you about whether they see these people as supportive and trusted, and the degree to which they feel trust in them.

-

If assessing a child/young person directly, building rapport will need to be centred on them, as much as the parent/carer who may be experiencing violence, if they are also present. The focus of the assessment will change from one centred on the adult to one centred around the child/young person, and the impact of violence on the carer/ parent-child relationship, as applicable. Remember a child victim survivor may have an enduring relationship with the perpetrator. For example, if this person is a parent. Obtaining the child’s views and wishes regarding both of the parents is necessary to meet the child’s wellbeing and developmental needs.

-

Where assessing risk directly with a child/young person, without a parent/ carer present, another appropriate professional should be engaged as an independent third person to support the child/young person.

1.12.1 Safe engagement with infants

Play-based support: If a victim survivor is very young, or has limited verbal communication, you may wish to seek support in understanding their play-related behaviour. Their behaviour can reveal a significant amount about what a child or young person is navigating. A professional with training in engaging with infants, such as a maternal child health nurse, behaviour specialist, early childhood teacher (who may be employed in early learning centres), or early primary teacher may be able to assist you in this engagement and consideration of their behaviours. Where they have an existing relationship with the victim survivor, they may be able to assist with contextualising behaviours, and/or providing further information about their play beyond your engagement.

Infants usually communicate a great deal about themselves through their play. When you communicate with an infant:

-

Observe closely to see their reactions and modulate your approach accordingly.

-

Look for any signs of physical violence, such as bruising or abrasions.

-

Remember that sudden moves and loud voices may be re-traumatising for infants, even if they are intended to be fun and engaging.

-

Where possible, sit at the child’s level (often this means on the floor) and play alongside them.

-

Remember that infants understand more than they can express verbally — talk about what you are doing as you are doing it.

-

Acknowledge what the child seems to be feeling, consciously modelling ways to validate both the emotions that the child has, and their expression of them.

Remember, eye contact is desirable in many cultures but not all. In the latter case, even young infants will have absorbed their parents’ cultural practices in this regard. In addition, infants generally look away if they feel overwhelmed.

1.12.2 Safe engagement for children and young people

Engagement with children and young people should be based on their age and developmental stage. You should consider whether the information needs to come from direct communication with the child/ young person, or if it could be obtained from other sources, including any appropriate adult who is not suspected of using family violence.

For many professionals, the conversation with a child or young person about whether they are experiencing family violence will take place in an organisational environment such as an office or clinical setting. Children and young people are more likely to engage with you at your office if the space is welcoming and inclusive.

However, if your workspace is not a safe environment or is not optimal for the child/young person’s needs, you should consider appropriate alternatives. This may include the child/young person’s home, or a playground, park or cafe. Settings that have movement, require limited eye contact, and there is something neutral to look at can make it easier for children and young people to communicate. For example, children and young people may prefer to talk with you whilst being driven somewhere or while playing, driving or walking.

Young people might have different views, needs and wants to their parent/carer, and you might feel a tension in supporting both parties. If your agency does not have a youth worker, consider asking a youth service to support and advocate for a young person.

1.12.3 Activities

Children and young people also tend to engage through age-appropriate play. Children and young people might struggle to find words to describe their experiences and label their feelings. Consider using age-appropriate communication aids such as drawing, dolls, puppets, or feelings/ strengths cards. It is preferable to seek advice or training on how to incorporate these into your practice.

Children and young people with communication barriers or are non-verbal, may also benefit from this form of engagement.

1.13 What's next?

Guidance on identifying and screening for family violence risk is outlined in Responsibility 2. All professionals who suspect that a person is experiencing family violence should use the guidance in the next chapter on how to identify the presence of family violence, including the use of the Screening and Identification Tool.

1. Organisations such as Scope and Communication Rights Australia may be able to assist.

2. Adapted from State of Victoria, 2018, Dhelk Dja: Safe Our Way, Cultural safety, page 31.

Responsibility 2: Identification of family violence risk

Responsibility 2 chapter of the Family Violence Multi Agency Risk Assessment and Management Framework: Practice Guides.

Download and print the PDF or read the accessible version:

Appendix 1 contains the observable signs of trauma that may indicate family violence. The document includes separate lists for adults, children and young people (Tables 1-5).

Appendix 2 contains the Screening and Identification Tool within a table of practice guidance.

Appendix 3 contains the Screening and Identification Tool as a standalone template.

Appendix 4 contains a flow diagram of response options and a basic safety plan.

2. Identification of family violence risk

2.1 Overview

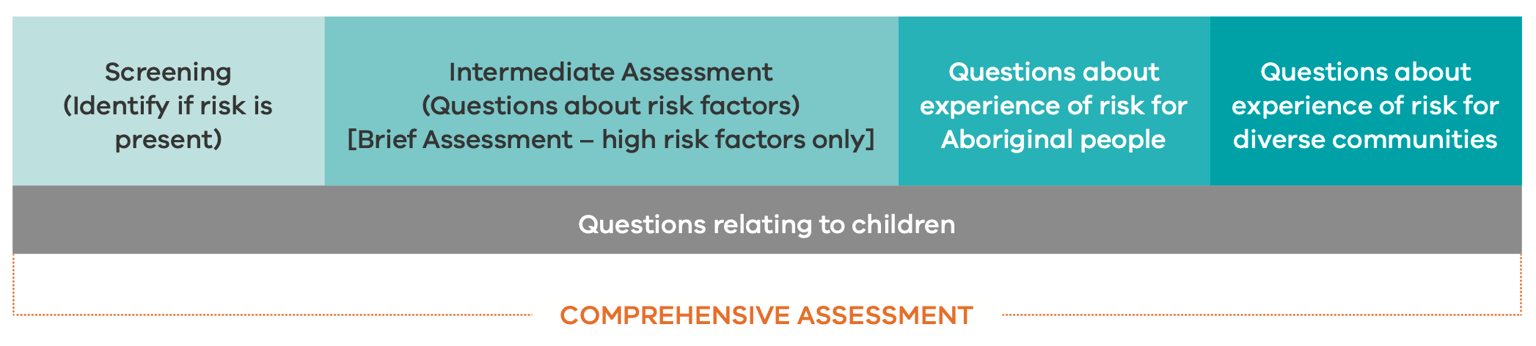

This chapter should be used when family violence is suspected but not yet confirmed.

This guidance will enable you to identify if family violence is present and undertake screening for an adult, child or young person to assist you to decide if further action and/or assessment is required. Specific guidance on identifying violence and use of screening tools with children and young people is outlined in Section 2.7 of this guide.

Only professionals who have received training to engage with perpetrators about their use of violence should do so. It can increase risk to a victim survivor to engage with a perpetrator when not done safely.

Key capabilities

All professionals should have knowledge of Responsibility 2, which includes:

- Awareness of the evidence-based family violence risk factors and explanations, outlined in the Foundation Knowledge Guide

- Being familiar with the questions to identify family violence, observable signs and indicators, using the Screening and Identification Tool and how-to-ask identification questions

- Using information gathered through engagement with service users and other providers via information sharing to identify signs and indicators of family violence (for adults, children and young people) and potentially identifying victim survivors. Information sharing laws and practice is further described in Responsibility 6.

Remember

Guidance which refers to a perpetrator in this guide is relevant if an adolescent is using family violence for the purposes of risk assessment with a victim survivor about their experience and the impact of violence. Risk assessment and management for adolescents should always consider their age, developmental stage and individual circumstances, and include therapeutic responses, as required.

2.1.1 Who should use the Screening and Identification Tool?

Appendix 2 contains the Screening and Identification Tool within a table of practice guidance. The Screening and Identification Tool as a standalone template is in Appendix 3.

All professionals should use the Screening and Identification Tool, either applied routinely when this is a part of your professional role or service, or only when indicators of family violence are identified.

Screening is not an activity that occurs only once by a single professional or within a service. In service settings where a person has multiple contacts, it is necessary to screen over time and at each contact to ensure any changes in the relationship or use of violence is identified.

Some organisations and workforces will undertake routine screening, asking every person accessing their service questions to screen for family violence (such as in perinatal settings or Youth Justice). Other workforces will only use the Screening and Identification Tool when they have identified indicators or signs of family violence risk through their regular service and are seeking to confirm the presence of family violence.

Identification (including through use of the Screening and Identification Tool) will support professionals to form their professional judgement about how to respond.

2.2 Structure professional judgement in identification and screening

Reflect on the model of Structured Professional Judgement outlined in Section 9.1 of the Foundation Knowledge Guide.

Identification and screening is the first opportunity to ask a victim survivor about their self-assessment of their risk, fear and safety, as well as some initial questions about family violence risk factors. These can be further informed by risk assessment and information sharing, described in later responsibility guides.

Identification and screening is the first step in understanding if family violence risk factors are present, and is informed by a person’s assessment of their own level of family violence risk (self-assessment). Observing signs and indicators of risk and asking screening questions about family violence support these two elements of Structured Professional Judgement.

2.3 Identification of screening for family violence

Identifying and screening for family violence means identifying that family violence risk factors are present. This can be done through observation of signs of trauma that may ‘indicate’ family violence is occurring, and/or confirming this by undertaking screening.

Screening involves asking questions defined in a ‘tool’ (provided in Appendix 3) to enable a person to disclose whether they are experiencing family violence. The questions are designed to identify information about evidence-based family violence risk factors. The Screening and Identification Tool includes some of the high-risk factors associated with an increased likelihood of a person being killed or almost killed. All of the questions in the Screening and Identification Tool should be asked, when possible.

Before beginning, you should discuss the purpose of the Screening and Identification Tool (or risk assessment) with the person. You should acknowledge that some of the questions may be confronting and difficult to answer but that they are important for assessing risk and identifying appropriate responses.

2.3.1 What are family violence risk factors?

The family violence risk factors are outlined with a short description in the Foundation Knowledge Guide in Section 8. Family violence risk factors are evidence-based factors that are used to:

-

identify if a person is experiencing family violence

-

identify the level of risk, and

-

identify the likelihood of violence re-occurring.

Responsibility 3 describes how to assess for risk factors, including determining the level or seriousness of risk.

2.3.2 Observable signs of trauma that may indicate that family violence is occurring

Family violence risk factors may be identified through observing signs or ‘indicators’ related to a person’s physical or emotional presentation, behaviour or circumstances. These signs are presentations of possible trauma, which may indicate family violence is occurring and can be expressed differently across a person’s lifespan, from infancy, childhood and adolescence1, through to adulthood and old age.

Appendix 1, Tables 1–5, contain a non- exhaustive list of signs of trauma which may indicate that family violence is occurring for adults and children.

These signs of trauma do not by themselves determine that family violence is occurring, they are ‘indicators’ only at this stage. These signs may also indicate that another form of trauma has occurred. If you suspect someone is experiencing family violence, it is important to ask the person screening questions about family violence.

Adults and children experiencing family violence may also not exhibit any of these signs and indicators. If you don’t observe any signs or indicators but think that something is ‘not quite right’, you should use prompting questions or the Screening and Identification Tool to explore whether family violence might be occurring.

2.3.2.1 Signs and indicators relating to age for children and young people2

Signs of trauma in a child or young person may indicate family violence or another form of trauma. Signs may be observed through the presentation, behaviour or circumstances of a child or young person. Some signs may relate to trauma from specific forms of family violence, including sexual abuse (indicated by) or emotional abuse (indicated by *).

Some signs may indicate a child’s experience of trauma or other circumstances outside of the family or home environment. Consider the wellbeing and safety of a child within and outside of the family context when observing these indicators.

Children’s behaviours may be driven by a range of underlying factors, including disability, developmental issues, and non-family violence related trauma and you will need to consider how these factors may be affecting or reinforcing each other. Significant changes in behaviour can indicate the presence of family violence and/or increased risk.

Observable ‘general’ signs of trauma for a child or young person of any age are listed in Appendix 1, Table 2. Signs can also vary considerably according to the age and stage of a child or young person’s development, and are listed in Appendix 1, Tables 3 and 4.

Sometimes the presence of family violence may be observed from a child’s circumstances and may relate to neglect due to the experience of family violence. Some signs or indicators of neglect are listed in Appendix 1, Table 5.

Guidance on whether to assess children and young people directly, or through asking questions of a parent/carer who is not using violence, is outlined at Section 2.7.

2.4 Using prompting questions with an adult support screening

You can use broad, prompting questions that lead into screening questions to begin the conversation. You can use your judgement on how to use these example questions or other prompting questions appropriate to the individual or their circumstances.

You can begin by asking open-ended, rapport-building questions about their wellbeing, for example:

-

“I’m pleased to see you today — how are things going?” [if Aboriginal — “Can I ask who are your mob?”]

-

“What has brought you here today?”

-

“Can you tell me what has been happening for you lately?”

-

“Tell me a bit about your family/home life/relationship with X?"

You can also frame prompting questions as part of routine or formal process used in your service to identify and screen for family violence risk. You can have a scripted question, such as:

- “In our organisation it is common that we ask questions about family violence so we can connect people with appropriate support. Is it ok if I ask you a few questions about how things are going at home/in your relationship?”

- “When we are concerned about someone, we always ask a set of questions to find out if they are experiencing violence or being mistreated in any of their relationships”

- “You have just let me know X (i.e. that you have recently separated). When any of our clients tell us this we ask a question about your experience at home and safety”

- “Is there anyone else in the family who is experiencing, seeing, overhearing, or being exposed to or aware of these things?”

You can also start by linking some of the observable indicators (Appendix 1) into the conversation.

- “I noticed that you appear to be experiencing X, is there something worrying you/you would like to talk about?”

You could use simple statements such as:

-

“Many people experience problems in their relationships.”

-

“I have seen people with problems like yours who have been experiencing trouble at home.”3

If an adult, child or young person responds to your prompting questions, you can ask the direct screening questions in the Screening and Identification Tool. These are purposely direct, because research indicates that victim survivors are more likely to accurately answer direct questions.

2.5 When to use Screening and Identification Tool

The Screening and Identification Tool as a standalone template is at Appendix 3.

Guidance on each question in the tool is at Appendix 2.

It is important to note that the Screening and Identification Tool has been developed to be used with adult victim survivors to identify family violence for both adult and child victim survivors.

The purpose of the Screening and Identification Tool is to identify:

-

If family violence is occurring

-

The victim survivor’s level of fear for themselves or another person

-

The person using violence/perpetrator.

The outcome of the Screening and Identification Tool will guide you on what to do next, that is, whether immediate action, further assessment and/or risk management is required.

If someone isn’t ready to respond to your questions about family violence, you need to respect this and let them know that if they are ready in future to talk about any experience, you are open to doing this.

The Screening and Identification Tool should be used:

-

When you suspect that someone may be experiencing family violence and have observed signs/indicators of family violence

-

To start the conversation if someone discloses they are experiencing family violence

-

If your workplace requires you to screen all individuals you work with for family violence (that is, ‘routine screening’ such as in antenatal/maternal child health settings).

At times, a victim survivor may want to give detailed answers about their experiences. The priority in this identification and screening stage is to identify the presence of risk and any immediate risk. This may mean you need to refocus or guide them back to a question. You can say you want to give them space and time to share their experience. However, if risk is identified as present and it is the role of another professional within your service or another service to continue to undertake intermediate or comprehensive assessment, you can sensitively contain the conversation around screening to ensure they do not have to tell their story multiple times (which can increase trauma).

Screening and identification should not be undertaken if the person suspected of using violence is present.

Your objective is to encourage the person to tell their story in their own words. You could lead into the questions by describing how the questions are structured, with a statement such as:

-

“I would like to ask you a series of questions that have ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘don’t know’ answers. They will help us work out what to do next together”

-

“We will start with questions about the person making you feel unsafe or afraid and then ask some questions about your level of fear and questions about children (if relevant).”

It is important to ask direct questions about family violence. Questions 1–4 support you to understand if family violence risk is occurring, the victim survivor’s level of fear for themselves or another person and the identity of the person using violence (the perpetrator).

Risk factors may change over time and some may increase in severity. A perpetrator may change their behaviours and their impact on the victim survivor may become more severe. If a risk factor has increased in severity, recently or over time, this should be noted as indicating an escalation in violence and a serious risk.

Frequency by itself is not always the indicator of the level of risk you should be asking further questions to understand if frequency has changed or escalated. This is particularly important for some high-risk factors and provides important information when considering if someone is at immediate risk.

Some key considerations when asking screening questions 1–4 is to look out for information about changes in frequency or severity which may indicate escalation and imminence of risk, particularly if change or escalation has occurred recently (further explored in questions 5–7).

How to move through the risk assessment questions:

- If the answer to a question indicates that family violence is not occurring no action is required relating to that risk factor/ question. Advise the individual that if this occurs in future to seek assistance

- If the answer to a question indicates family violence is occurring, proceed to the next question(s) as outlined below.

Remember

Screening questions are designed to be asked to an adult victim survivor about their risk or risk to any children and/or young people. The risk for children and/or young people correlates to the level of risk for the adult.

Risk to children and young people should be identified independently and informed by risk identified as present for the adult victim survivor (for example, who may be a parent/ carer).

2.6 Why someone might not disclose family violence, even if asked

There are many reasons why people do not feel comfortable or ready to disclose family violence. For example, a person might:

- Not be ready.

- Not identify their experience as family violence.

- Have had negative experiences when disclosing it in the past.

- Be scared that the perpetrator will find out that they have talked to you and the potential repercussions for their safety.