Download and print the PDF or read the accessible version:

Appendix 5 contains the Adult Brief Assessment Tool reflecting high-risk factors only.

Appendix 6 contains the Adult Intermediate Assessment Tool.

Appendix 7 contains the Child Victim Survivor Assessment Tool.

Appendix 8 contains the Adult Intermediate Assessment Tool within a table of practice guidance about each question to support response.

3. Intermediate risk assessment

3.1 Overview

Professionals should refer to the Foundation Knowledge Guide and Responsibilities 1 and 2 before commencing intermediate risk assessment.

This chapter should be used to guide intermediate risk assessment of the level or ‘seriousness’ of family violence risk — for either an adult or a child1. This assessment may be done directly after disclosure or identification and screening (see Responsibility 2), or to assess changes in family violence risk over time.

Key capabilities

This guide supports professionals to have knowledge of Responsibility 3, which includes:

- Asking questions about risk factors.

- Understanding the evidence-base of how questions link to the level of risk.

- Using the process of Structured Professional Judgement in practice.

- Using intersectional analysis and inclusive practice.

- Using the Brief or Intermediate Assessment Tools.

- Forming a professional judgement to determine seriousness of risk, including levels ‘at risk’ ‘elevated risk’ or ‘serious risk’.

An ‘intermediate’ level risk assessment may be undertaken using either:

- The Brief Assessment Tool reflecting high-risk factors only. The Brief Assessment Tool is for professionals providing time-critical interventions only. This assessment can be used to inform a full intermediate assessment at a later point when time or the situation allows

- The Intermediate Assessment Tool includes questions about a broader range of evidence-based risk factors experienced by adults and questions about risk to children

- The Child Assessment Tool contains a summary of adult risk factors, questions for an adult about a child’s risk and a separate set of questions for direct assessment of an older child or young person.

Guidance on undertaking an intermediate assessment to determine risk for children and young people is at Section 3.8 of this guide.

Practice considerations to assist your decision-making on how to assess risk for a child or young person include:

- creating opportunity for a child’s personal agency and voice to be heard

- individually assess their experience of risk

- wherever possible, collaborate with a parent/carer who is not a perpetrator

- reinforcing responsibility is with the perpetrator.

Remember

Guidance which refers to a perpetrator in this guide is relevant if an adolescent is using family violence for the purposes of risk assessment with a victim survivor about their experience and the impact of violence. Risk assessment and management for adolescents should always consider their age, developmental stage and individual circumstances, and include therapeutic responses, as required.

After an intermediate risk assessment, a professional may escalate the risk assessment (through secondary consultation or referral) to a comprehensive assessment to be undertaken by a specialist family violence worker.

3.1.1 Who should undertake intermediate risk assessment?

This guide should be used by professionals whose role is linked to, but not directly focused on, family violence. As part of, or connected to your core work, you will be engaging with people:

- at risk of experiencing family violence

- in crisis situations from family violence

- who are perpetrating family violence.

Do not engage directly with perpetrators about their violence if you are not trained to do so.

For further information please refer to your organisation’s family violence policies and procedures or the Responsibilities Decision Guide for Organisational Leaders (Figure 2) in the Foundation Knowledge Guide.

3.2 Structure professional judgement in intermediate assessment

Reflect on the model of Structured Professional Judgement outlined in Section 9.1 of the Foundation Knowledge Guide.

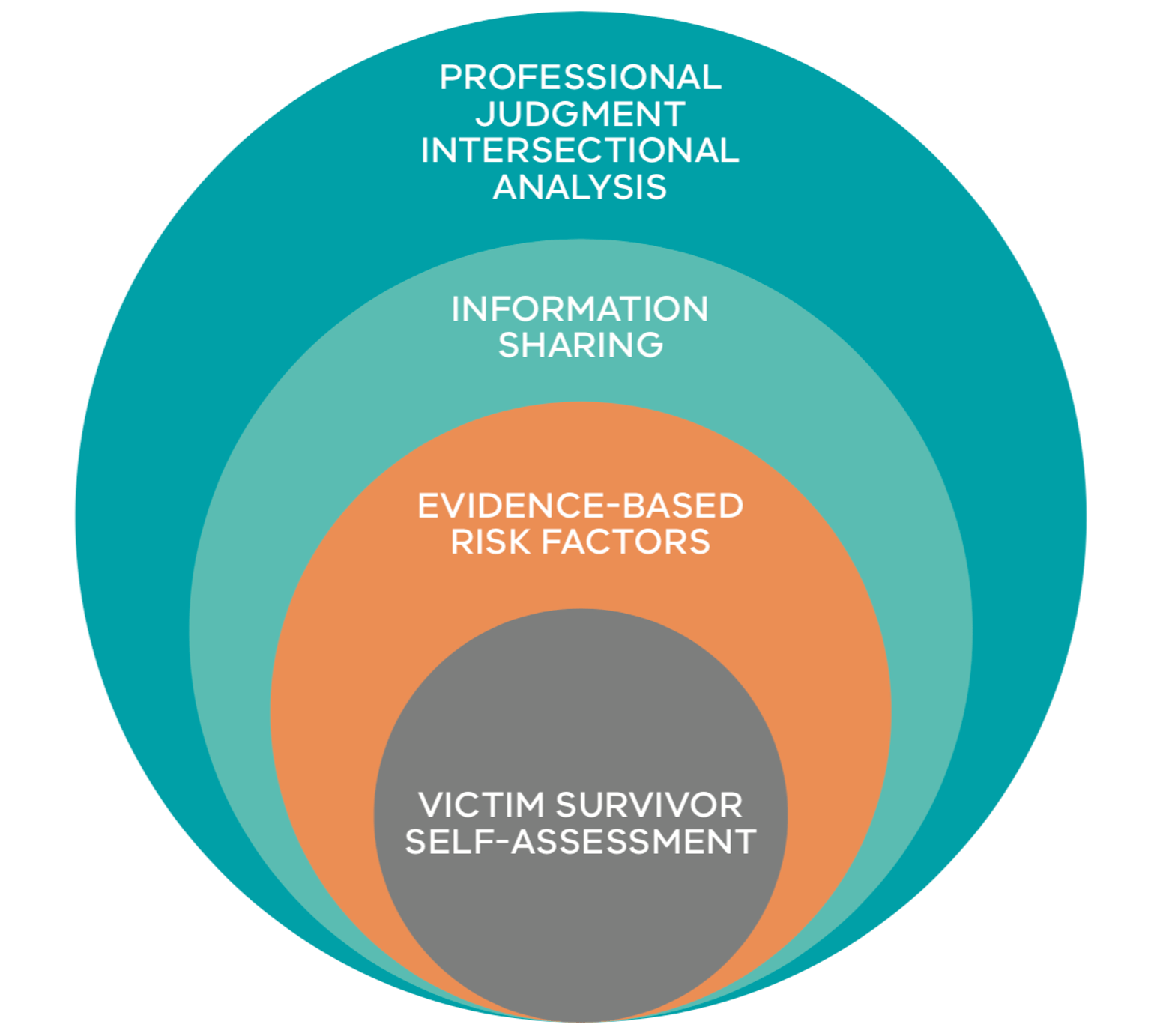

Structured Professional Judgement is the practice model that underpins risk assessment to support you to determine the level of risk and inform risk management responses. The Brief and Intermediate Tool questions are designed to support victim survivors to tell you about their experience of family violence, to inform you about the current level of risk and history of violence.

Risk assessment relies on you or another professional ascertaining:

- a victim survivor’s self-assessment of their level of risk, fear and safety

- the evidence-based risk factors identified as present.

You can gather information to inform this approach from a variety of sources, including:

- interviewing or ‘assessing’ the victim survivor directly

- requesting or sharing, as authorised under applicable legislative schemes, with other organisations and services about the risk factors present or other relevant information about a victim or perpetrator’s circumstances.

Secondary consultation and information sharing are more fully described in Responsibilities 5 and 6, and in the Family Violence Information Sharing Guidelines.

An intersectional analysis lens must be applied as part of Structured Professional Judgement. This means bringing an understanding that a person may have experienced or be experiencing a range of structural inequalities, barriers and discrimination throughout their life. These experiences will impact on:

- their experience of family violence

- how they manage their risk and safety

- their access to risk management services and responses.

Professionals should consider any additional barriers for the person and make efforts to address these.

Your analysis of these elements and application of your professional experience, skills and knowledge are the process by which you determine the level of risk.

3.2.1 Information sharing to inform your assessment

Information sharing can inform your risk assessment.

See Responsibility 6 for further guidance on understanding what is ‘risk-relevant’ information when sharing and, if authorised, the Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme Guidelines and Child Information Sharing Scheme Guidelines on how to make requests and share information.

You can request information from other professionals or services concurrently with undertaking risk assessment with a victim survivor. There are some circumstances where you may request information before assessing risk with a victim survivor. Examples may include:

- Where you cannot engage with a victim survivor to undertake an assessment with them due to their fear of discovery by a perpetrator or third party

- Where high-risk factors are identified as present by a professional or service and it is not safe, appropriate or reasonable for a victim survivor to engage in an assessment at that time and risk management responses are required to intervene to reduce or remove (manage) an identified threat.

3.3 Intersectional analysis and inclusive practice in intermediate assessment

Experiences related to a person’s identity, including experiences of barriers and discrimination, can influence how a victim survivor might:

- Talk about and understand their experience of family violence or recognise that what they have experienced is a form of family violence.

- Understand their options or decisions on what services to access based on actual or perceived barriers. This may be due to past discrimination or inadequate service responses from the service system, including from institutional or statutory services.

- Perceive and talk about the impact of their experiences of family violence.

Be open to the ways that victim survivors might present and ask about and engage with them in ways that are responsive to their lived experiences. This may include:

- Asking about and recording concerns the victim survivor has and consider these in how you undertake risk assessment and the risk management responses you develop with them.

- Seeking secondary consultation and possible co-case management with a service that specialises in responding to diverse communities in the context of family violence (see Responsibility 5, 6 and 9).

- Engaging in a culturally appropriate manner, including offering to contact or engage with other agencies and/or the services of a bi-cultural worker

- Discussing any protective concerns you hold for children with the victim survivor.

- Where an adolescent is using violence discussing with an adult victim survivor the:

- Safety, risk and needs of the adolescent’s siblings and other family members.

- Any immediate risks to the safety, security and development needs of the adolescent using violence.

- The victim survivor’s capacity to take action to protect themselves, other children and family members.

It is critical for you to understand and explore:

- A victim survivor’s individual circumstances, including how the impact of family violence might be expressed.

- The underlying reasons for any reluctance the victim survivor has to use a service or engage with the service system.

- The relationship between the victim survivor/s (including each child and/ or family members) residing in the household to ascertain other risks of family violence for each person e.g. sibling abuse.

Remember

Secondary consultations with appropriate support professionals and services can assist you to provide appropriate, accessible, and culturally responsive services to the victim survivor.

Remember to challenge your biases. This can minimise the chance that any concerns you may hold arise from cultural or other misunderstandings.

See Responsibility 1 and the Foundation Knowledge Guide for more information on intersectional analysis, inclusive practice and providing a safe and accessible environment.

3.4 How to use the intermediate or child assessment tool

Standalone templates for the:

- Intermediate Assessment Tool is in Appendix 6

- Child Assessment Tool is in Appendix 7.

A table of practice guidance on each question in the Intermediate Assessment Tool is in Appendix 8.

The purpose of the Intermediate Assessment Tool is to:

- Identify the range of family violence behaviours being experienced by asking questions based on risk factors (this includes questions about risk to any children in the family/household)

- Consider the information gained through the assessment and apply Structured Professional Judgement to determine the level of risk — this will support you to understand a perpetrator’s individual behaviours and characteristics to assess whether the (adult or child) victim survivor is at an increased risk of being killed or almost killed

- Understand the level of risk at a point in time or changes in risk over time.

Questions in the Intermediate Assessment Tool are grouped according to:

- Risk-related behaviour being used by a perpetrator against an adult, child or young person

- Self-assessment of level of risk (adult victim survivor), and

- Questions about imminence (change and escalation).

There are two templates for an intermediate risk assessment:

- Assessing an adult by asking them questions about their risk (Intermediate Assessment Tool)

- Questions in the Intermediate Assessment Tool are grouped according to:

- Risk-related behaviour being used by a perpetrator against an adult, child or young person

- Self-assessment of level of risk (adult victim survivor), and

- Questions about imminence (change and escalation).

- Questions in the Intermediate Assessment Tool are grouped according to:

- Assessing a child or young person (Child Assessment Tool):

- Has a section about risk factors present from an adult victim survivor assessment. This also enables you to carry over information about a parent/ carers risk and identify factors that are relevant to the child’s assessment

- Provides additional questions that can be asked to a child/young person (if age and developmentally appropriate, safe and reasonable). These can be tailored in the language used to ensure they are age and developmentally appropriate.

An intermediate risk assessment may be guided by the victim survivor’s narrative and what they are ready to talk about. That is, the questions do not need to be asked in a strict order of the template.

Some assessments can be explored over a number of service engagements as you build rapport and enhance a professional relationship with the victim survivor. The questions are direct and explicit, because research indicates that victim survivors are more likely to accurately answer direct questions.

3.5 When to use the brief assessment tool

The Brief Assessment Tool as a standalone template is in Appendix 5.

The decision to use either the Brief or full Intermediate Risk Assessment Tool depends on whether a time-critical intervention is required, or there are other constraints to using the full Intermediate Assessment Tool. The Brief Assessment Tool is appropriate to use with adults and young people nearing adulthood only.

Brief assessment will be undertaken by frontline staff and critical responders, such as paramedics, in time-critical interventions. A brief assessment will be used when:

- There is limited time to engage with an individual.

- It is not safe to seek further detail about the family violence beyond high-risk factors.

- It immediately follows an incident.

- It is during a crisis intervention.

The Brief Assessment Tool covers all the high-risk factors and is a sub-set of the full Intermediate Assessment Tool. High-risk factors are linked to an increased likelihood of the victim survivor being killed or nearly killed.

A brief assessment can be used by yourself or another professional to later inform a full intermediate assessment, or comprehensive assessment by a specialist family violence practitioner.

All guidance following this section will refer to the Intermediate Assessment Tool and is applicable if the Brief Assessment Tool is being used.

3.6 Using prompting questions

“The question is not what is important. It is the answer. We need to be careful that our focus is on the answer rather than preparing for the next question.”

Family Violence Intake Worker

You can start an intermediate assessment conversation by providing context to why you are asking the questions, your role and the role of your organisation.

You can then use prompting and open- ended questions to support the victim survivor to tell their story in their own words, before moving on to ask specific questions in an assessment to draw out important information about risk factors.

Remember

Using prompting questions is also explored in Responsibility 2.

Prompting questions for children and young people are outlined in Section 3.8.

Your objective is to encourage the victim survivor to tell their story in their own way. This will assist in making the risk assessment feel less like a checklist of questions. Prompting questions can also be used during risk assessment to encourage conversation.

If you are working in a universal service that the person is accessing for another purpose, you may seek to use prompting questions to introduce the assessment and its purpose.

You could lead into the questions by describing the assessment structure, with a statement such as:

- “You have let me know that you are experiencing family violence from [name of person/relationship]. Risk assessment is the next step we take in this organisation”

- “It sounds like you are really worried about (adolescent’s/perpetrators) behaviour and the impact it is having on you and/or other children/family members. It’s important to understand the risks of this behaviour. I’d like to ask you some questions to understand this better”

- “I would like to ask you a series of questions that have ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘don’t know’ answers. The questions are quite direct as it is important for me to understand the risk you may be experiencing from the behaviour of [name of person using violence, if disclosed]”

- “This will help me to understand how serious the risk is, and what we will decide together to do next”

- “We will start with questions about the [name of person using violence, if disclosed] and then ask about your level of fear and questions about children (if there are any)”

- “Usually we undertake the assessment over a short period of time (in a single sitting or over a few sessions). This is important as risk level is understood as a ‘point-in-time’ assessment. If we continue to work together, letting me know about changes in risk over time can help me to understand if your level of risk has changed and if we need to change how we are responding to keep you safe”

- “If you need a break at any point during the assessment, just let me know”

Key prompting questions to ask prior to introducing the risk assessment tool, that will open the conversation, build rapport and trust, and elicit important information relevant to risk, include:

- “Could you tell me about the most recent incident?”

- “How long has this been going on?”

- “In your view, is the situation getting worse?”

- “What is the most serious thing that has happened?”

- “Do you think the situation will continue?” If not, why not? If yes, why?

After you have introduced and completed asking direct questions about family violence risk factors in the assessment tool, you should then explore more detail about the risk factors through open-ended questions, such as:

- “We have talked about the last incident. Can you tell me more about previous incidents? Have you noticed a pattern to their behaviour?”

- “What do they do that hurts / scares / controls you or your children?”

- “What do they do that gets in the way of your relationship with your children / the way you parent them?”

- “What do they do that makes you afraid for yourself, (if an adolescent) your other children, or themselves (in the case of self-directed violence, for example, including self-harm or threats to suicide)?”

- “Have they ever hurt or threatened to hurt your pets?”

- “Is there something I should be asking you that I have not asked?”

Remember

Women may be reluctant to disclose violence for a range of common reasons, such as: fear of the consequences (including of the perpetrator carrying out threats of violence or escalation, or involvement of statutory services or justice interventions); concerns they won’t be believed; shame; or thinking that they are to blame for the abuse. A further range of reasons are outlined in Responsibility 2.

Throughout the assessment process, you should explore if some of these reasons are present so you can respond appropriately and support the person to feel safe to disclose.

3.7 Understanding the assessment process and risk levels

In a full intermediate assessment you will seek answers to all questions, or as many as possible. This can be done through conversation or direct questioning, as appropriate.

Your analysis of the elements of Structured Professional Judgement and application of your professional experience, skills and knowledge are the process by which you determine the level of risk.

Remember, you can seek secondary consultation from a specialist family violence service if, for example, some high- risk factors are present that may require a specialist response, or there is a perceived difference between what a person has told you and what you have observed.

3.7.1 Responses to questions

The questions in the Intermediate Assessment Tool are seeking to elicit answers about the presence of family violence risk factors. It is key that you believe a person if they are disclosing that family violence is occurring2. The responses to questions are ‘yes’, ‘no’, and ‘not known’. If the answer is ‘yes’ there are some follow- up questions in Appendix 8 that can further inform your assessment.

If you cannot ascertain the answers to a question, then select ‘not known’. This may be if you don’t have the opportunity to ask the question or if you don’t get a clear response. You should make a comment if you haven’t been able to ask the question, especially if the question relates to a high- risk factor.

A risk factor may be indicated if the person discloses that the risk factor is present. It may also be indicated if you have noticed observable signs, or you have received the information from another professional or service, or a third party. The context and circumstances of risk factors that are identified should be noted in comments.

3.7.2 Risk levels or ‘seriousness’

Before undertaking risk assessment, it is important that you understand the levels of risk which denote ‘seriousness’, outlined below.

Table 1: Levels of family violence risk

There are three recognised levels of risk, ‘at risk’, ‘elevated risk’ and ‘serious risk’.

‘Serious risk’ can also ‘require immediate protection’, or not. This can change and escalate over time.

| At risk | High-risk factors are not present. Some other recognised family violence risk factors are present. However, protective factors and risk management strategies, such as advocacy, information and victim survivor support and referral, are in place to lessen or remove (manage) the risk from the perpetrator. Victim survivor’s self-assessed level of fear and risk is low and safety is high. |

| Elevated risk | A number of risk factors are present, including some high-risk factors. Risk is likely to continue if risk management is not initiated/increased. The likelihood of a serious outcome is not high. However, the impact of risk from the perpetrator is affecting the victim survivor’s day-to-day functioning. Victim survivor’s self-assessed level of fear and risk is elevated, and safety is medium. |

| Serious risk | A number of high-risk factors are present. Frequency or severity of risk factors may have changed/ escalated. Serious outcomes may have occurred from current violence and it is indicated further serious outcomes from the use of violence by the perpetrator is likely and may be imminent. Immediate risk management is required to lessen the level of risk or prevent a serious outcome from the identified threat posed by the perpetrator. Statutory and non-statutory service responses are required and coordinated and collaborative risk management and action planning may be required. Victim survivor’s self-assessed level of fear and risk is high to extremely high and safety is low. Most serious risk cases can be managed by standard responses (including by providing crisis or emergency responses by statutory and non-statutory (e.g. specialist family violence) services. There are some cases where serious risk cases cannot be managed by standard responses and require formally convened crisis responses. Serious risk and requires immediate protection: In addition to serious risk, as outlined above: Previous strategies for risk management have been unsuccessful. Escalation of severity of violence has occurred/is likely to occur. Formally structured coordination and collaboration of service and agency responses is required. Involvement from statutory and non-statutory crisis response services is required (including possible referral for a RAMP response) for risk assessment and management planning and intervention to lessen or remove serious risk that is likely to result in lethality or serious physical or sexual violence. Victim survivor self-assessed level of fear and risk is high to extremely high and safety is extremely low. |

3.7.3 Determining seriousness or level of risk

The process of applying the Structured Professional Judgement model includes identifying and analysing the presence of risk factors to help you determine the level of risk. This includes high-risk factors and how, based on the perpetrator’s behaviour and circumstances, they have changed or escalated in frequency or severity.

Children and young people’s risk should be independently assessed, and your assessment of them will be informed by the risk level for an adult victim survivor, and vice versa. Further guidance on assessing risk to children and young people (both directly and indirectly) is in Section 3.8 of this chapter.

Every question contained in the Intermediate Assessment Tool is connected to the family violence risk factors outlined in the Foundation Knowledge Guide. Some risk factors are described as ‘high risk factors’ that strong evidence shows are crucial indicators that the victim survivor is at an increased risk of serious injury or death.

REMEMBER

In considering the level or seriousness of risk:

- A lower level of risk is determined if an assessment indicates:

- Risk factors are not present or are rarely present.

- The high-risk factors are not present.

- A higher level of risk is determined if an assessment indicates:

- Self-assessment of risk is high.

- Risk factors are present, particularly high-risk factors.

- Risk factors, particularly high-risk factors, have changed/escalated in severity, likelihood (has continued and past behaviour indicates it will occur in future) and timing (change in frequency or escalation), and the degree of change indicates a more serious level of risk.

3.7.4 Reviewing risk assessment over time

The level or seriousness of family violence risk is dynamic and may change or escalate over time due to:

- Changes or escalation in frequency or severity of the perpetrator’s behaviour to a victim survivor

- A change in each individuals’ circumstances (that can reflect the domains of protective factors, as well as specific risk factors relating to circumstances for adults and children)

- Changes in perpetrator behaviour toward a child or young person in response to their developmental stage.

Remember

You may determine the risk level based on a single assessment.

Risk is also dynamic and can rapidly change, resulting in changes to the level of risk. Ongoing risk assessment and management is a part of all professionals’ responsibilities.

A key to understanding seriousness of risk is to understand how risk escalates or changes in severity or frequency over time.

It is therefore important to regularly revisit risk questions with an individual. Understanding a victim survivor’s risk over time involves undertaking risk assessment at a ‘point in time’ and comparing with previous risk assessments/information (that is, analysing the trend and change of behaviours used by the perpetrator). This process of conducting point-in- time assessment and review of previous assessments is referred to as ‘ongoing assessment’. Further detail on ongoing assessment is outlined in Responsibility 10.

A person may not disclose all information about their experience of family violence, and professionals can use their judgement when they have concerns that they have not gained a complete understanding of the risks that may be present.

3.7.5 Practice considerations in determining level of risk:

Victim survivor’s self-assessment of risk, fear and safety:

Evidence is clear that an adult victim survivor’s self-assessment of risk is a crucial input to your assessment. Where self- assessment indicates that the adult victim survivor considers themselves (or any child victim survivor) to be at serious risk, this is key information about the level of risk, even if other risk factors have not been identified as present.

An adult’s self-assessment of fear, risk and safety is also relevant to assessing the risk to a child. An adolescent/young person who is closer to adulthood may be asked to self- assess their risk.

There is no current evidence base that a younger child’s self-assessment of risk is reliable in determining their level of risk. However, asking the child or young person about their experience of fear may support validation of their experience by supporting them to feel heard, and for you to consider in your risk management responses.

Practice tip

Evidence shows that adult victim survivors are often good predictors of their own level of safety and risk and that this is the most accurate assessment of their level of risk. However, some victims may minimise their level of risk. Therefore, it is critical that you check if the victim survivor’s behaviour matches their reported level of fear and ask questions to explore this. A victim survivor- led approach to risk assessment and safety management recognises that clients are the experts in their own safety and have intimate knowledge of their lived experiences of violence3.

Self-assessment for adult victim survivors is explored through a set of questions in the Intermediate Assessment Tool in Appendix 8.

When introducing the self-assessment, you can ask the victim survivor to rate on a scale from 1 (not afraid) to 5 (extremely afraid), for example:

“How afraid of them are you now?”

Such as a 1-5 scale comprising:

- 1 not afraid

- 2 slightly afraid

- 3 moderately afraid

- 4 very afraid

- 5 extremely afraid

You can also ask how their current fear compares to the victim survivor’s experience at their most afraid:

“What is the greatest level of fear you have experienced in your relationship?”

This can assist you to explore what was happening for the victim survivor at that time to further understand the history of violence. A victim survivor’s level of fear should also guide you on whether any immediate management responses are required from current violence or threats of repeated violence that has occurred in the past.

Remember

Serious risk may be indicated from a single incident or experience of a high-risk factor only. However, it is also important to explore whether risk factors have occurred over a period of time, and changes to severity and frequency over time.

Severity:

Severity can be explored by asking about current risk factors and history of violence and their impact on the victim survivor. Often risk factors that indicate serious risk based on the severity of violence can be identified, such as sexual assault, physical harm, strangulation or choking, particularly when this violence has resulted in a loss of consciousness.

An example of exploring this question may be:

- “Have they ever physically assaulted you?”

(If yes)

- “Can you describe the assault/s?”

(Allow them to reply — then ask)

- “Were you ever hospitalised due to an injury sustained during an assault?”

- “Has the frequency or severity of the assaults changed in any way recently?”

Risk factors may change over time and some may increase in severity. A perpetrator may change their behaviours and their impact may become more severe to the victim survivor. If a risk factor has changed to increase in severity, recently or over time, this should be noted as indicating an escalation in violence and a serious risk.

Frequency

Frequency by itself is not always the indicator of the level of risk — you should explore further to understand if frequency has changed or escalated. This is particularly important for some high-risk factors.

If a victim survivor has disclosed a risk factor is present, you can explore changes in frequency and escalation by providing examples of time periods and asking, “How frequently?” to establish a baseline — before asking “has this changed in frequency or escalated recently? Over time?”.

Change or escalation in frequency or severity:

After you have explored frequency, you can also ask related questions about change in behaviours/risk factors that might indicate escalation in either severity or frequency.

If the types of behaviour the perpetrator is using have changed in terms of frequency or severity, this would indicate escalation of risk. It is a strong indicator of serious risk if the perpetrator is using more specific threats or has increased their use and severity of violence.

You should also consider the scale of the escalation and the impact on the victim survivor.

Practice tip

Exploring risk factors used by the perpetrator enables you to concentrate on assessing the perpetrator’s behaviour, beliefs and attitudes, personality and situational factors that increase the risk posed by them.

It is important to explore with the victim any (changes in) circumstances that may lead to an escalation in violence from the perpetrator. For example, a recent:

- Separation may challenge the perpetrator’s self-belief about their role or position within the family, such as a partner or parent.

- Court order excluding the perpetrator from the family home.

- Family Court order removing or restricting access to children.

3.8 Intermediate risk assessment for children and young people

Note: The prevalence of family violence against women and children, and against women as mothers and carers, is well established and recognised across the service system. Acknowledging this, the following section on risk to children uses gendered language to describe experiences for mothers, including damage to the mother/child bond caused by perpetrator behaviours. However, it should be noted that this guidance also applies to all forms of families and parenting.

Language in this section of ‘mother/carer’ refers to a parent/carer who is not using violence (not a perpetrator).

Children and young people affected by family violence are victim survivors in their own right, with unique experiences of family violence and its impacts. Children and young people should have their risk independently assessed. This should then be considered alongside the risk being experienced by mother/carer to collectively inform your determination of the level of risk for each family member.

When assessing risk for children and young people, you should:

- Reflect on previous guidance that outlined risk factors specific to a child or young person (Foundation Knowledge Guide).

- Build on your observation of signs of trauma that may indicate family violence in children and young people (Responsibility 2).

- Build on any response to screening questions (Responsibility 2).

The Child Assessment Tool can be completed from information received from a range of sources, including from:

- The mother/carer about a child or young person’s experience of risk. Noting also that a mother/carers own experience of risk is relevant to the experience of risk for a child.

- The child or young person directly about their experience.

- Other professionals and services. You should proactively seek and share information relevant to a child’s experience of family violence and, their wellbeing and safety, as authorised by the Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme and Child Information Sharing Scheme, or other legal authorisation, to inform your assessment.

The Child Assessment Tool is divided into 2 sections:

- Questions to ask a mother/carer about a child/young person. You can complete the list of risk factors present for a mother/carer from a previous assessment undertaken with them, if applicable.

- Questions designed to ask a child or young person directly.

The approach you choose to how you assess risk for a child should consider what is appropriate, safe and reasonable in the circumstances and may include asking questions:

- To a child/young person directly (appropriate to their age/developmental stage), with or without their mother/carer present.

- Of a mother/carer to indirectly assess the risk for a child/young person.

- To another appropriate adult family members or professionals who work with the child/young person to indirectly assess the risk for a child/young person.

Some direct questions may be asked of children from around the age of 3+ years, noting that this will need to be appropriate to the age and developmental stage of the child, and where possible with a mother/ carer present. Prompting questions for children and young people may be most appropriate to ask directly to this age group (see Responsibility 2).

In deciding whether to assess a child or young person directly or indirectly, you should take into account their age, development stage and circumstances. You should also consider whether it is appropriate, safe and reasonable to do so.

In some cases, an adolescent using family violence may be experiencing risk themselves. For example, adolescents may be:

- Experiencing family violence from another family member.

- At risk of self-harm or suicide.

- Using violence, which may or may not also relate to developmental delay or psychosis (whether drug-induced or otherwise).

Responses to an adolescent’s experience and/or use of family violence (if applicable) must include therapeutic support and be appropriate for their age and developmental stage.

Practice tip

Some professionals use language such as ‘protective parent’ or similar, which seeks to acknowledge the protective actions a mother (parent/carer) who is not a perpetrator has taken to protect the child in situations of family violence.

This term should not be considered to infer that a non-violent parent/carer is responsible for preventing violence. The responsibility for using violence and its impacts on adult and child victim survivors sits with the perpetrator alone.

3.8.1 Practice considerations for directly or indirectly assessing risk for a child or young person

Remember

The MARAM Framework principles guide professionals to recognise:

- Family violence may have serious impacts on the current and future physical, spiritual, psychological, developmental and emotional safety and wellbeing of children, who are directly or indirectly exposed to its effects, and should be recognised as victim survivors in their own right.

- Services provided to child victim survivors should acknowledge their unique experiences, vulnerabilities and needs, including the effects of trauma and cumulative harm arising from family violence (see Foundation Knowledge Guide Section 10.3).

While consent is not needed to share information in order to assess or manage risk to a child under the Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme, or to promote their wellbeing or safety under the Child Information Sharing Scheme, professionals are encouraged to take all reasonable steps to seek and obtain the views of the child and/ or the mother/carer who is not a perpetrator before sharing the information.

The practice considerations outlined below aim to assist professionals to put these principles into practice.

Practice considerations to inform your decision-making on how to assess risk for a child or young person reflect the MARAM Framework principles above, as well as a trauma and developmental lens, and include the following:

- Create opportunity for a child’s personal agency and voice to be heard: enquire to understand children and young people’s own identity and experience.

- Individually assess their experience of risk: directly assess risk with the child or young person where appropriate, safe and reasonable to do so; identify protective factors and develop the required management responses.

- Wherever possible, collaborate with a mother/carer: support strengthening/ repairing the relationship and bond between the child and mother/carer.

- Reinforce that risk and its impacts are the responsibility of the perpetrator: in all communication with the mother/carer and the child or young person, make sure they are aware they are not responsible for a perpetrator’s use of violence.

Remember

The risk level of a mother/carer who is a victim survivor is highly relevant to the risk level of any child victim survivors, and vice versa. Still, it is critically important that, wherever possible, you create the opportunity in your risk assessment practice to hear from a child or young person directly to conduct a specific and individual risk assessment for each child or young person in a family.

To determine if assessing risk directly with a child is appropriate, safe and reasonable for their age, developmental stage or circumstances, consider:

- Is it currently a crisis situation?

The safety of children, young people and adult victim survivors is paramount, and a child’s risk may be indirectly assessed through a mother/carer in crisis situations.

- Who is the primary service engagement with/who is present?

You should start assessment of the client who is present. You should also identify other family members, including children, who may also be at risk of or using family violence (in some families there may be more than one person).

- Is the child present or able to attend the service?

If the child is not present or not your primary client, consider if it is appropriate to ask a mother/carer to bring the relevant child or young person to a subsequent appointment to enable direct assessment.

- Are you suitably trained in working directly with children and young people?

If not, are there staffing and service arrangements that can be made to support you to work directly with a child or young person to assess their risk?

What other services should be engaged to assist in direct assessment of a child or young person?

If assessing risk directly:

- Is there a parent/carer (usually a mother) or appropriate safe adult who can support the child or young person in the assessment?

- Have you determined if there is a ‘protective’ parent/carer (who is not a perpetrator)? Are they aware of the risk being experienced by the child/young person?

- Is your service or another service engaged with the parent/carer to gauge their understanding of the child’s experience of risk?

- What are the views and wishes of an older child or ‘mature minor’ to a parent/ carer being present? — or an alternative support person present?

- Is there an alternative appropriate adult (such as another adult family member or other professional) who works with this child who can support risk assessment with a child or young person?

Note: None of the practice considerations should limit the recognition of children and young people as victim survivors in their own right. Through each approach to assessing risk for children and young people, you should maintain a lens on their individual experiences, vulnerabilities and needs, and respond to the impacts of trauma and harm.

3.8.2 When assessing risk to children you must also consider their wellbeing and needs

Professionals need to use their professional judgement of the individual circumstances for each case as to how they respond to the wellbeing and needs of both the child and adult victim survivor. When undertaking risk assessment and management planning, you and the mother/carer who may also be a victim survivor, need to consider the wellbeing and needs of the child or young person, including the vulnerability of the child, such as the in/ability of children to take action and move away from danger when violence is occurring, and to privilege thinking about the child’s wellbeing and needs, especially as the age and developmental stage of the child mean they are not able to do this for themselves.

Further guidance on understanding a child or young person’s wellbeing and needs can be undertaken through assessing protective factors in Section 3.9.

3.8.3 Challenges to assessing risk to a child or young person, or through a parent/carer or other appropriate third party

To facilitate direct risk assessment with a child or young person, you may need to address barriers to engagement by parent/ carers disclosing risk to children and young people. These may include:

- parental shame

- fear of statutory intervention and child remova

- seeing questions as intrusive and undermining, particularly if a perpetrator has used violence to attack the child- mother bond

Undermining the mother-child bond

Perpetrators often undermine an adult victim survivor’s (usually mother’s) bond with their child. To understand the impact of violence on children and young people you should maintain a lens on the child-mother/carer bond and parenting.

This is commonly based in social norms and gender stereotypes about women as primary carers who are responsible for children’s health, wellbeing and development. Attacking the mother/carer in this role has direct impacts on both the child and their mother/carer. Additionally, perpetrators may undermine a mother/ carers relationship and attachment with other children or stepchildren in the family/ household.

Often perpetrators expose children and young people to family violence against their mother/carer as a tactic to attack or undermine the child-mother/carer bond. Exposure to family violence is a direct risk for children and young people that can disrupt their attachment and development, and impact their safety, needs and wellbeing.

You should:

- Recognise and respond to the impact family violence has on children and young people including wellbeing and needs, emotional, social, and educational challenges, and attachment or bond with the mother/carer.

- Not blame the mother/carer or children/ young people for the family violence or its impacts.

- Strengthen the child-mother/carer bond and parenting confidence and capability that may have been undermined by the perpetrator’s family violence behaviours.

- Advocate to services and systems, in partnership with the mother/carer, so that they are not held responsible for managing the perpetrator’s actions and behaviour or its impact on children and young people.

More detail on how perpetration of family violence impacts on women (and other caregivers, kin or guardians) as parents is provided in the Foundation Knowledge Guide in Section 10.2.

Other barriers to engagement

Engagement with children about violence may also be hindered if the mother/carer is concerned about:

- Re-traumatising or upsetting children by talking about the violence with them.

- Mandatory reporting requirements and the repercussions for them and their child.

- Being judged and having their parenting/ caring role undermined instead of responsibility being placed on the perpetrator for the child/young person experiencing family violence (directly or from exposure).

These concerns from mothers/carers may override understanding their child/children’s experience of living with family violence. Addressing the fear and stigma related to children’s experience of violence with the parent/carer can support building trust to engage with the assessment process.

Building trust and rapport

You can build trust with an adult victim survivor by affirming their role as a mother carer. This can help you to assess children’s risk, both directly and indirectly. You can discuss the child or young person’s needs and wellbeing with the mother/carer, including any issues relating to the impacts of trauma for the child, such as signs observed through their behaviours (see Responsibility 2, Appendix 1).

You can also support a mother/carer to repair the child-parent/carer bond, by modelling safety, help-seeking behaviours and being aware, affirming and responding to the experience of children (fear, risk, safety, needs and wellbeing).

An effective approach to building rapport and trust with a mother/carer can be by having a conversation with both a child/ young person and their mother about the risk being experienced by the child/young person. This will involve you asking some questions to:

- the mother/carer about the child or young person’s experience, as well as

- direct questions to the child or young person

It is important to give permission, space and time to the child or young person to discuss sensitive matters, including their experiences of risk, safety and wellbeing.

If an adolescent is being assessed as experiencing violence, and they are also using violence, do not include the adolescent in a joint conversation with a parent carer, but ask if they would like another appropriate support person present.

Note: Following assessment and depending on the level of risk, you may determine that a report to Child Protection or a referral to a service with expertise in child and infant development, such as Child FIRST, and/or mental health may also be appropriate (for example, child or family services). If so, consider how you may support the parent/ carer who is not a perpetrator in this process. (See Responsibilities 5 and 6 for further information on secondary consultation and referral).

Guidance on approach to assessment of a child or young person (directly or indirectly)

Table 2 outlines approaches to assessment with children based on their age and developmental stage.

Assessment can occur directly with children and young people, if safe, appropriate and reasonable to do so, which includes considering their age and developmental stage.

Table 2: Approaches to risk assessment of children

| Age | Approach to assessment of a child or young person (direct or indirect) |

|---|---|

Infants and younger children (0–5 years) | If infants are suspected of being at risk from family violence, a full intermediate assessment of the adult victim survivor and the child must be done. Assess indirectly by asking questions with the mother/carer who is not a perpetrator, considering your observation of signs of trauma that may indicate impact from family violence in play and communication or other interactions with the mother/carer, or siblings (see Responsibility 2, Appendix 1 for signs of trauma that may indicate family violence). The Intermediate Assessment Tool includes questions about both the child’s experience of risk, and the experience of the adult victim survivor. Remember the experience of the child and their parent/carer who is a victim survivor are strongly related. |

Older children and young people (6–18 years) | An older child may be assessed directly, if appropriate, safe and reasonable to do so, which should consider their age, developmental stage and circumstances. The Child Assessment Tool includes questions for assessing older children (see Appendix 7). For young people aged 15–18 years, considering their age and developmental stage and circumstances, it may be appropriate to ask adult-focussed questions in the Intermediate Assessment Tool (see Appendix 6). For example, for a young person experiencing violence in an intimate partner relationship, it may be appropriate to ask direct questions that are broader than the questions specific to children and young people. If assessing risk directly:

If assessing risk indirectly, use the Child Assessment Tool questions directed to a parent/carer about risk experienced by a child or young person (see Appendix 7). |

3.8.4 Approach to assessing risk directly with children or young people

Your assessment must focus on the risk and needs of the children or young people. A list of family violence risk factors for children and young people is included in the Foundation Knowledge Guide.

Table 3 of the Foundation Knowledge Guide also outlines risk factors relating to a child’s circumstances to support you to identify external risk to a child’s wellbeing or safety. If external risk factors relating to a child’s circumstances are present, this may also indicate the presence of family violence. If a child or young person is experiencing risk in the community, consider how this is cumulatively impacting them, and also how you might manage both causes of risk.

Consider if the child or young person is at risk from people outside the family, such as in the community, in clubs or other social engagements. This may indicate there is an environment of polyvictimisation (that is, multiple sources of harm) that may connect to a child’s family violence risk.

Rapport is particularly important, as a child or young person will need to have some confidence in you before answering the risk assessment questions. Use child friendly activities and age and developmental stage appropriate supports for talking with young children. Refer to Section 1.5 “Building rapport” in Responsibility 1.

Use a trauma-informed approach to understand the child’s behaviour in terms of their experiences of abuse and fear. Considerations for children must be appropriate to their developmental stage and circumstances and should include:

- Their own views of their needs, safety and wellbeing.

- Their current functioning at home, school and in other relevant environments.

- Their relationships with family members and peers.

- Their relationship with the perpetrator.

- Their relationship with other people experiencing family violence in the family or household, particularly if it is their mother.

- Their sense of cultural safety, where relevant.

- The level of support available to them if they are a child with a disability.

- Their developmental history, including experiences of family violence or other types of abuse or neglect.

When assessing children, it is important to remember that they will have their own unique experiences of family violence and its impacts. This may include either positive or negative feelings towards the relationship they have with the perpetrator. During the assessment you should validate the child’s feelings and continue to keep the perpetrator’s accountability in focus as well as the child and each family member’s safety.

Create a place of emotional and physical safety for the child before you ask the assessment questions. Remember, it is ideal to directly ask an older child or young person about how safe they feel and what they need in order to feel safe.

Start by asking prompting questions such as:

- “What are the things that make you feel happy or that you like to do?”

- “Is there someone at home that makes you feel safe?”

- “Do you think you could talk to them if you were scared or worried?”

- “Do you feel unsafe or scared of anyone living in your home?”

Further prompting questions for children are in Responsibility 2.

3.9 Identifying protective factors for victim survivors (adults, children and young people)

Following risk assessment, you should explore with the victim survivor what ‘protective factors’ are present for them (and if relevant, any children). Protective factors alone do not remove risk. However, if protective factors are present these can help to mitigate or reduce risk and promote stabilisation and recovery from violence.

Where protective factors are identified, they must be confirmed before assessing if they mitigate or reduce the identified risks or their impacts (short or long-term). Accepting what a parent/carer describes as a protective action should be explored to ensure it is an effective protection.

Responsibility for family violence sits with a perpetrator, and often it is their actions which undermine the ability of a mother/carer to establish protective factors for themselves or their children. The ‘protectiveness’ of any protective factor is only useful to the degree a perpetrator is willing or unwilling to undermine or ignore that factor.

Some protective factors are also values- based judgements that reflect social advantage. Inability to establish protective factors due to circumstances is not representative of a deficit on the part of a victim survivor.

Remember

Protective factors may mitigate or lessen risk. They can also build resilience and support recovery where family violence has occurred. Strengthening protective factors is a key element of safety planning, reflected in the Table 4 in Responsibility 4. These may already be present and described in a safety plan or may be established through safety planning and other risk management processes.

You should take into account existing protective factors, but do not rely on them too heavily without considering the victim survivor’s view of whether the factor can protect them or has previously protected them or a child or young person from the actions of a perpetrator.

Table 3: Protective factors for adults and children

| Protective factors for adults and children | |

|---|---|

| Systems intervention |

|

| Practical/ environmental |

|

Strengths-based (Identity / Relationships / Community) |

|

You should take protective factors into account when considering risk level, but not rely on them to determine the level or seriousness of risk.

Consider an adult victim survivor’s view on whether the factor can protect them to inform:

- Your understanding of whether they are aware of the seriousness of risk.

- How to build on recognised protective factors through risk management, including safety planning.

Strengths-based protective factors for children

Adult and child victim survivors can have different perspectives on what protective factors are present for children. For adults, protective factors for children are often centred on resilience to promote stabilisation and recovery through communication, imparting values and modelling safe behaviours and relationships.

For children and young people, protective factors are important to understand the context of how they are impacted by violence and how they can be supported to strengthen their resilience.

Table 4: Strengths-based protective factors that promote children’s resilience

| Child-based Protective Factors |

|---|

Consider the age, stage and vulnerability of the child. Age is a significant factor in children’s resilience. Older children may be able to engage in activities outside the home and develop supportive relationships. Consider whether the child has/is:

|

For Aboriginal children, cultural pride and a strong sense of Aboriginal spirituality and community are important protective factors.

Connection to culture and community are also important for children from culturally, linguistically and faith diverse communities.

| Parent/carer actions to promote child’s protective factors |

|---|

The parent/carer:

|

| Family-based Protective Factor |

|---|

|

3.10 Misidentification of victim survivor and perpetrator

Refer to further guidance in the Foundation Knowledge Guide in Section 11.3 and Responsibility 7 on determining a predominant aggressor and misidentification.

In some circumstances, misidentification of the victim survivor and perpetrator occurs. Misidentification is where a victim of family violence is categorised as a perpetrator (respondent in criminal or civil proceedings) — or where a perpetrator has misrepresented themselves as a victim of violence.

Evidence and research demonstrate that relatively few men in heterosexual relationships are solely experiencing family violence or intimate partner violence. In heterosexual relationships, men are much more likely than women to be using a number of repeated, patterned forms of violence to dominate and control over time.

Through the course of your assessment if you are uncertain about who is using violence, you should refer the person to a specialist family violence service or seek secondary consultation.

Practice tip

In all circumstances where a man is initially assessed as or claiming to be a person experiencing family violence in the context of a heterosexual relationship, you should refer him to a men’s family violence service for comprehensive assessment or to the Victims of Crime Helpline. His female (ex)partner must always be referred to a women’s family violence service for assessment, irrespective of whether they are thought to be the victim survivor or the perpetrator.

It is important, however, that professionals recognise that misidentification can occur in any community or relationship type.

3.11 What's next?

The outcome of the intermediate risk assessment will inform your decision- making on what to do next. If family violence is present, you must use the guidance in Responsibility 4 on undertaking risk management on how to respond.

For example, next steps for risk management could include:

- Immediate action (calling police on 000 or making a report to Child Protection or Child FIRST/ child and family services).

- Secondary consultation or information sharing (seeking or sharing) to further inform your assessment.

- Safety planning and risk management.

- Referral to a Specialist Family Violence Service, or other services (if required).

Specialist family violence services can provide secondary consultation or receive referrals for comprehensive assessment and specialist risk management. This action:

- Must occur if the assessed level of risk is ‘serious risk’ or ‘serious risk and requires immediate protection’

- May occur if the assessed level of risk is ‘elevated risk’.

If a child or young person is experiencing risk that requires you to make a referral to Child Protection or to share information or seek secondary consultation with a service with expertise in child and infant development, refer to guidance in Responsibilities 5 and 6.

Refer to guidance on the following responsibilities:

- Responsibility 4: Intermediate risk management

- Responsibility 5: Seek consultation for comprehensive risk assessment, risk management and referrals

- Responsibility 6: Contribute to information sharing with other services (as authorised by legislation).

3.11.1 Document in your organisation’s record management system

It is important that you document the following information in your service or organisation’s record management system:

- Consent and confidentiality conversation outcome.

- Each risk assessment you undertake, the level of risk for each victim survivor and reasoning.

- Children’s details and if present — also if children’s own assessment has been completed.

- Any other relevant information such as relating to protective factors and the circumstances of the victim survivor, perpetrator and other family members

- If an interpreter was used in the assessment.

- If a support person was present and their relationship to the victim survivor.

- Contact details for the victim survivor, including method of contact (such as text before call) and time it may be safe to make contact.

- Emergency contact details of a safe person if the victim survivor cannot be contacted.

1. Intermediate assessment can be undertaken directly following disclosure from a victim survivor, without a screening assessment being first undertaken.

2. If you are uncertain about the identity of the victim survivor or perpetrator, such as where you think a perpetrator may be misrepresenting themselves as a victim survivor, refer to Section 10.2 of Foundation Knowledge Guide on how to respond.

3. ANROWs National Risk Assessment Principles, 22.

4. ANROWS, National Risk Assessment Principles for domestic and family violence: Companion resource, page 28.

5. http://providers.dhhs.vic.gov.au/criminal-offences-improve-responses-ch…

6. https://aifs.gov.au/cfca/publications/domestic-and-family-violence-preg…

7. https://www.aaimh.org.au/resources/position-statements-and-guidelines/ (Position Statement on Infants and Family Violence)

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid.

10. Australian Institute of Family Studies (2015). Children’s exposure to domestic and family violence.

11. Dawson, J. (2008). What about the children? The voices of culturally and linguistically diverse children affected by

family violence. Melbourne: Immigrant Women’s Domestic Violence Service.

12. Edleson JL 1999, ‘Children’s witnessing of adult domestic violence’, Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 14(8): 839–870

13. Harne L 2011, Violent Fathering and the Risks to Children, The Policy Press, London

14. Morris, A., Humphreys, C., & Hegarty, K. (2015). Children’s views of safety and adversity when living with domestic violence. In N. Stanley & C. Humphreys (Eds.), Domestic violence and protecting children: New thinking and approaches (pp. 18-33). London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

15. Bagshaw, D. et al (2011). The effect of family violence on post-separation parenting arrangements Family Matters, (86).

16. Brownridge, D (2006), ‘Violence against Women Post-Separation’, Aggression and Violent Behavior, vol. 11, no. 5, pp. 514–30.

17. Kirkwood, D. (2012). ‘Just Say Goodbye’ Parents who kill their children in the context of separation. Domestic Violence Resource Centre Victoria, Discussion paper (No.8).

18. Section adapted from Victorian Government Department of Human Services (2012). Assessing children and young people experiencing family violence A practice guide for family violence practitioners.

19. Segrave, M (2017) Temporary migration and family violence: An analysis of victimisation, vulnerability and support.

Melbourne: School of Social Sciences, Monash University

20. Laing, L. (2003). Domestic Violence in the Context of Child Abuse and Neglect. Australian Domestic and Family Violence Clearinghouse, Topic paper.

21. Edleson, J. L. 2001. ‘Studying the co-occurrence of child maltreatment and domestic violence in families’, in Domestic Violence in the Lives of Children: The Future of Research, Intervention, and Social Policy, eds S. A. Graham- Bermann & J. L. Edleson, American Psychological Association, Washington, D.C.

22. Bowlby J 1969, Attachment and Loss, Basic Books, New York

23. Bunston W & Sketchly R 2012, Refuge for Babies in Crisis, Royal Children’s Hospital Integrated Mental Health Program, Melbourne, p 26

24. DHHS, with acknowledgement of Humphreys, C., Connolly, M., & Kertesz, M., University of Melbourne (2018). Tilting our practice: A theoretical model for family violence. Victorian Government, Melbourne.

Updated