The RCFV noted that lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) people experience unique forms of family violence, and highlighted the lack of information, data and education that currently exists in this area.132 This section highlights the family violence issues faced by LGBTI communities, existing data standards and guidelines used to collect information, and the challenges in collecting this data. A data collection standard is presented which is recommended to be used for the collection of information about LGBTI people by agencies and service providers who respond to family violence or offer family violence services.

Terminology and definitions

Although lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex communities are often grouped together because of a shared history of discrimination, each of these communities and the barriers they face are distinct.133 There are many people that make up these diverse groups, which extend beyond the five letters of ‘LGBTI’. However, this framework refers collectively to ‘LGBTI communities’, as this is the term used by the RCFV.

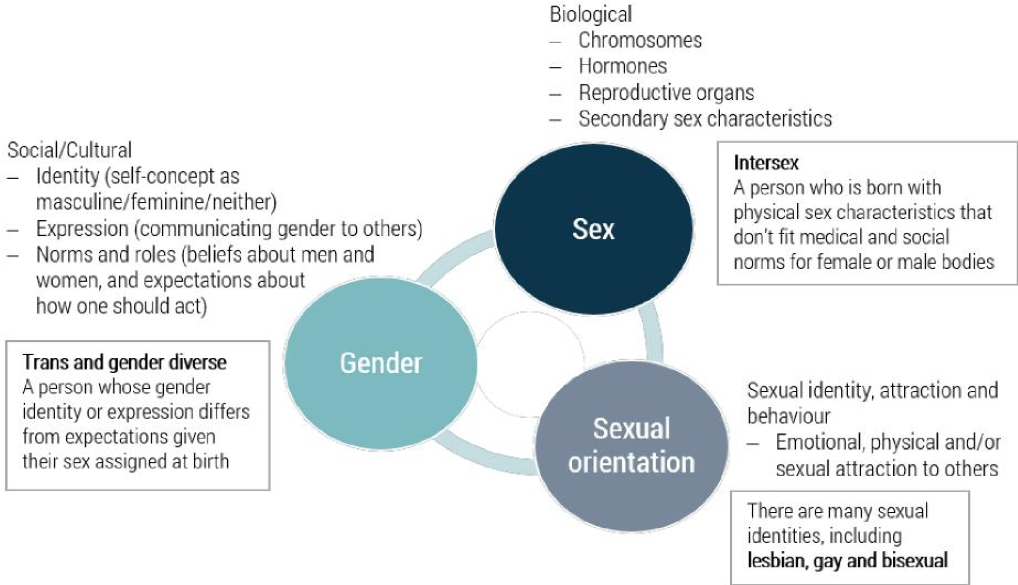

LGBTI communities describe themselves through the identification of their gender, sex, sexual orientation and intersex variation in a variety of ways. Definitions used in this section for gender identity, sex, sexual orientation and intersex can be found in both the ‘Data collection standard for collecting information about LGBTI people’ and the ‘Glossary’. The diagram below provides a basic overview of each concept and shows that while gender, sex and sexual orientation are connected to each other, they are also distinct. Additionally, there is more than one definition that exists for these concepts and associated terminology.

www.slideshare.net/jayembee/introduction-to-gender-minorities134

Family violence in LGBTI communities

Volume five of the RCFV report provides detailed information regarding what is known about the experience of family violence in LGBTI communities, and recommendations to address these issues. Summarised below are key points regarding prevalence, some of the unique forms of family violence in these communities and barriers to LGBTI services.

Prevalence

Currently, little is known about the prevalence of family violence in LGBTI communities. Available Australian research indicates that intimate partner violence in LGBTI communities is as prevalent as it is in the general population,135 with transgender and intersex people experiencing a higher prevalence of intimate partner violence compared to lesbian, gay and bisexual people who are not transgender and not intersex. Transgender women in particular are at greater risk of hate crime and sexual assault.136 Research in Australia regarding family violence in LGBTI communities beyond intimate partner violence is minimal.

Contributing circumstances and specific presentations of family violence risk

While it is vital to acknowledge that family violence is overwhelmingly committed by men against women,137 this focus has contributed to the lack of awareness of family violence experienced by LGBTI people. Assumptions can be made regarding family violence incidents which contribute to this. For example, an incident involving two men living together may not be recognised as family violence by police, and when viewed through the lens of heterosexual intimate partner violence, an assumption made that they are housemates. This could also be a contributing factor to some LGBTI people not recognising that what is happening to them constitutes family violence, which in turn may decrease the number of LGBTI people reflected in family violence data. Heteronormativity and heterosexism can also manifest in LGBTI relationships and this can contribute to the gendered drivers or presentations of risk in these communities.

In addition to the types of family violence which exist in the general community, there are specific ways that family violence may be present or experienced by LGBTI people. These include the following examples:

- emotional abuse:

- threatening to disclose someone’s gender identity, sex, sexual orientation or intersex variation (that is, outing someone) as a form of control

- telling a partner they will lose custody of their children as a result of being outed

- transphobic abuse whereby a person deliberately misgenders their transgender partner, ridicules their body or gender identity, or stops them from taking hormones or accessing services138

- a perpetrator claiming that the police, justice system or other support services are homophobic, biphobic or transphobic and won’t help the victim

- telling a person they deserve violence because they are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender or intersex

- telling a partner that the abusive behaviour is normal for a gay relationship, and that the abuse is mutual or consensual139

- sexual abuse, such as coercing sex through manipulation of the victim’s shame related to their sexual or gender identity

- physical violence committed by a family member due to their homophobia or transphobia

Under-reporting and barriers to accessing services

A small number of LGBTI-specific family violence support services and referral pathways exist, but there is currently a lack of services working with female perpetrators. Thorne Harbour Health (previously the Victorian AIDS Council) run the only Men’s Behaviour Change Program (ReVisioning) for gay or bisexual men in Victoria. Such services are often working over capacity with limited funding, and may be scarce or non-existent in rural, regional and remote areas.140

Trans and gender diverse people face particular barriers in escaping family violence and accessing housing support services. This is partly based on a lack of services designed to assist these communities.141

In addition, if service providers and agencies do not recognise the unique experiences of people in LGBTI communities, family violence may go unidentified and services may be inaccessible or inappropriate for both victims and perpetrators of family violence.

Why do we need to collect information about LGBTI people?

There is a lack of information, data and education both within LGBTI communities and in the broader community regarding family violence experienced by LGBTI people. The collection of information about LGBTI people can assist in addressing the gaps in data, and service response, which currently exist. Additionally, it was noted in consultation that many people feel supported and seen when their identity is represented in demographic data collection processes. It is acknowledged that questions regarding gender identity, sex, sexual orientation and intersex variation are personal, and may be seen by some as intrusive. With increased awareness and training, organisations will be better equipped to collect this information in an appropriate and inclusive way. Summarised below are key issues that were noted either in the RCFV findings or were found through research and consultation in regards to the increased demand for information about LGBTI people, and current gaps in information.

Increased demand for information about LGBTI people

Several submissions to the RCFV noted the importance of improved data collection in regards to LGBTI communities. The submission from Gay and Lesbian Health Victoria (GLHV) stated that enhanced data collection processes within the family services sector (utilising appropriate and sensitive approaches) would assist in the provision of important information for ongoing service development.142 The joint submission to RCFV from Safe Steps Family Violence Response Centre and No to Violence (NTV) recommended that:143

- the Victorian Government:

- supports agencies and government departments to review and update data collection capabilities to enable comprehensive information to be gathered on LGBTI communities

- supports and resources the creation of a state-wide data collection strategy for both family violence agencies and LGBTI organisations, which includes amending current data collection systems to ensure that consistent disaggregated data on LGBTI can be collected appropriately

- consultation needs to occur with LGBTI communities by agencies and policy makers as to howto ethically and respectfully collect relevant data.

Gaps in information

In recent years, following social and legislative reforms, LGBTI Australians have begun to be explicitly included in various public policies, programs and initiatives. However, many existing administrative data sets do not include categories to record if a person is LGBTI. This contributes to a significant information gap on the experiences of LGBTI people, and on their use of services. Further, family violence within LGBTI communities can also be under-reported due to narrower definitions that focus on intimate partner violence. It was noted in consultations for example that family members may commit violence against a child or sibling when they ‘come out’. There is currently limited data on the prevalence of this type of family violence.

More broadly, relationship type data are collected by some agencies and surveys such as the ABS Personal Safety Survey (PSS) and Crime Victimisation Survey (CVS), and when used in combination with a person’s sex or gender has been used to infer the number of same-sex relationships experiencing family violence (for example, a female victim in an intimate partner relationship with a female perpetrator). However this doesn't adequately capture the range of LGBTI people or relationship types. For example, victims who are bisexual but in a heterosexual relationship, relationships involving transgender or intersex victims, and victims experiencing family violence outside of an intimate partner relationship. It also relies on those collecting data to identify the relationship accurately, without making assumptions, and on data analysis and reporting systems that can facilitate more complex reporting and analysis.

Due to the lack of comprehensive data about LGBTI people, policy decision-makers must turn to LGBTI-targeted studies for evidence. Such studies are highly valuable but are unable to represent all LGBTI people, as coverage of the populations of interest is often limited, and not all LGBTI people are engaged with LGBTI communities.144

Challenges in current data collection practices

Regardless of an organisation’s willingness to collect information about gender, sex, sexual orientation and intersex variation, there are specific challenges that exist regarding data collection from LGBTI communities that organisations need to be aware of and consider. It is important to note that these challenges should not deter an agency from collection; rather, they should inform the organisation in their preparation for data collection. Challenges that are specific to a particular data item are explored under ‘Data collection standard for collecting information about LGBTI people’ on page 56. The challenges listed below are in addition to those discussed on pages 12 to 18, which are relevant to all priority communities within this framework.

Lack of knowledge about LGBTI communities

In order to collect high quality data, agencies need to be aware of and understand the needs of diverse LGBTI communities so that they may collect information appropriately, and provide an appropriate response. The joint submission to the RCFV from Safe Steps and NTV revealed that awareness of distinct LGBTI communities was variable among non-LGBTI specific service providers resulting in a lack of clarity around how to respond to subgroups and their specific needs.145 Additionally, it was noted in consultations that service providers and agencies may have unconscious bias, and make assumptions about a person’s gender identity or sexual orientation. If organisations lack knowledge about LGBTI communities, they may not feel comfortable asking about gender identity, sex, sexual orientation or intersex variation. Further, LGBTI people are not seen by all as groups as particularly vulnerable, despite extensive evidence regarding the stigma and discrimination they have experienced.146

Reluctance to disclose

Throughout consultation, it was acknowledged that some people will not be willing to disclose their gender identity, sexual orientation, sex or intersex variation. While attitudes are gradually changing, discrimination towards LGBTI people is still prevalent.147 Many do not trust police and the justice system, due in part to a history of discrimination, and the perception that they will not be taken seriously or believed. People may fear that an agency or service will be homophobic, transphobic or biphobic, or that the service won’t know how or be able to help them. In order to feel safe, they may have to hide their gender identity or sexuality, and by seeking help they may fear that this will further fuel discrimination against them. Additionally, unlike most other demographic information collected, the identity of a person who is LGBTI may not be known by people around them.148 There may also be a fear of disclosing to someone they already know in the community. As a result, some may fear the impact of revealing this information, so it is understandable that they may not feel comfortable or safe disclosing.

A person may give a different response to questions regarding gender identity, sexual orientation, sex or intersex variation, depending on the context of the situation. For example, the reason why the data are being collected, who will see the data, and the social or cultural setting.

Existing data standards

There is very little that exists in Australia in regards to data standards for collecting statistical information from LGBTI communities, despite social and legislative changes that have occurred in recent years. In 2013, the Sex Discrimination Act 1984 (Cth) was amended to introduce new protections from both direct and indirect discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation, gender identity and intersex status in many areas of public life.

Sex and gender

The legal protections provided by the change to the Sex Discrimination Act 1984 (Cth) are complemented by the Australian Government Guidelines on the Recognition of Sex and Gender. These guidelines recognise that an individual may identify as a gender other than the sex they were assigned at birth, or may not identify exclusively as male or female, and that this should be reflected in records held by the government.149

| Australian Government Guidelines on the Recognition of Sex and Gender (the Guidelines) |

|---|

|

The Guidelines:

The Guidelines commenced on 1 July 2013, and state that all Australian Government departments and agencies are expected to progressively align their existing and future business practices with these Guidelines by 1 July 2016. The Guidelines’ preferred approach is for Australian Government departments and agencies to collect gender information rather than sex. They acknowledge that people may identify as a gender other than the sex they were assigned at birth, and that people may not identify as exclusively male or female. The Guidelines propose that a third category for gender and sex is to be collected and recorded as X (indeterminate/intersex/unspecified).150 |

The ABS released the Standard for Sex and Gender Variables (the ABS Standard) in 2016. It was developed with consideration to the Guidelines, and replaced the Standard for Sex Variable 1999. The introduction of the ABS Standard is a move towards being able to collect data from trans and gender diverse communities, as it includes information regarding the distinct concepts of gender and sex, and its classification is no longer binary (ie. ‘female’ and ‘male’ only). The ABS Standard introduced a third category for both sex and gender of ‘other’, with the 2016 Census being the first in Australia to include this third category (when a special form was requested). The ABS Standard follows the Guidelines’ approach regarding the collection of gender rather than sex, and states that sex should only be collected when there is a legitimate need to collect it.

There are limitations to the Guidelines and the ABS Standard in their current forms. The ABS Standard states that further breakdown of the third ‘other’ category is recommended only when undertaking an in-depth social study.151 This may promote the idea that people who do not identify as female or male do not always need to be included in data. 152 Without consistent inclusion (where possible and appropriate), it is not possible to create an evidence base for these populations. Additionally, the ‘other’ category has been considered stigmatising,153 and amongst groups consulted in the development of this framework, this term was not favoured. The ABS Standard uses terminology recommended by the Guidelines, in that “terms such as ‘indeterminate’ and ‘intersex’ are variously used to describe the third category of sex”.154 The Sex and Gender Advisory Group155 have stated that the use of the term indeterminate implies a lack of a determined category. The group notes that people who do not identify as women or men in terms of gender and, separately, people whose bodily characteristics are not considered stereotypically female or male, are not ‘indeterminate’ and often have clearly determined ways of categorising themselves.156 Additionally, the group considers the use of X to represent intersex as inappropriate and inaccurate in capturing data from intersex people.157 The National LGBTI Health Alliance’s White Paper also noted that most people who are intersex do not wish to be considered as a third sex, and many identify their sex as female or male.158 These current limitations show that the ABS Standard in its current form may not be effective in accurately capturing data from these diverse populations.

Research has been undertaken on, and some changes made to, gender standards internationally. In 2015, Statistics New Zealand introduced the Statistical Standard for Gender Identity. This standard classification has three response categories; ‘male’, ‘female’ and ‘gender diverse’, and recommends that ‘gender diverse’ has a write-in facility to allow respondents to fully describe their gender identity. ‘Gender diverse’ has a further level of classification for outputs which has four categories.159 The Office for National Statistics (ONS) in the United Kingdom, in collaboration with the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC), have undertaken research into the collection of gender identity. Whilst the focus of their research has largely related to the inclusion of questions in the Census, it also looked at other options for meeting data requirements, starting with the exploration of administrative data.160

Sexual orientation

There is no ABS standard that currently exists in Australia for the collection of sexual orientation data. The ABS General Social Survey (GSS) included a question regarding sexual orientation for the first time in 2014, and over half a million people (approximately 3% of the Australian adult population) identified as gay, lesbian, bisexual or another sexual orientation which was not heterosexual. Whilst the GSS does not ask questions regarding family violence, results indicated increased vulnerability in related areas for those who did not identify as heterosexual, such as discrimination, homelessness and mental health conditions.161

A single standardised measure of sexual orientation is contained in most Statistics Canada data sets, and in the United States, multiple measures of sexual orientation are often present in data sets from the National Center for Health Statistics.162 In the United Kingdom, the National Health Service (NHS) has created an information standard for collecting sexual orientation data, in collaboration with the LGBT Foundation. The standard “provides the mechanism for recording the sexual orientation of all patients/service users aged 16 years and over across all health services with responsibilities for adult social care in England where it may be relevant to record this information”.163 The question set is based on research on sexual identity conducted by the ONS and EHRC, and on current practice by organisations which collect sexual orientation information. Their proposed question has the following seven response options; heterosexual or straight, gay or lesbian, bisexual, other sexual orientation not listed, person asked and does not know or is not sure, not stated (person asked but declined to provide a response) and not known (not recorded).164

Data collection standard for collecting information about LGBTI people

The data items included in this data collection standard are based on what is currently recommended in practice and research, and the findings of our consultations with organisations in Victoria.

There are some privacy implications related to the collection of data items in this standard due to their sensitive nature, and relevant privacy legislation including the Health Records Act 2001 (Vic) and the Privacy and Data Protection Act 2014 (Vic) should be considered by data custodians when collecting and storing this information. Further information about privacy and security considerations is provided on page 18.

All data items in this data collection standard should only be used in the appropriate service context. For example, it may be inappropriate to ask about someone’s sexual orientation during the first interaction with a person in a crisis situation. Before using a data item in this standard, the information that will be gained from it needs to be considered. The purpose of collecting data needs to be made clear to the client, and should be able to be linked to either a direct service response or referral to an appropriate service. The communities that make up ‘LGBTI’ are diverse, and it is not possible to capture information from these populations in a single data item. However, it may not be appropriate to use all four data items. While this data collection standard aims to inform organisations of the most appropriate data items to use to collect data from LGBTI communities, it is not intended as a guide for when to collect this data.

It has been previously noted that organisational change and staff training relating to LGBTI inclusive practice is vital, but its importance is emphasised again here. It is important to avoid making assumptions about a person’s gender identity, sex, sexual orientation or intersex variation. Without educating staff, there is a risk of misgendering165 or incorrectly interpreting a family violence situation, and causing harm to clients. Staff need to be trained in recognising when it may not be appropriate to ask, and in how to sensitively and respectfully collect data. For information regarding some organisations which offer LGBTI inclusive training in Victoria, please refer to ‘Training and resources’.

Although mentioned previously in the framework, it is worth noting again the importance of confidentiality, and how this specifically relates to LGBTI communities. As stated in the Rainbow Tick guide to LGBTI-inclusive practice, “disclosure has the potential to significantly impact on an LGBTI person’s safety, health and wellbeing and their social connectedness...this may create real tensions for the LGBTI consumer regarding confidentiality and unintended disclosure”.166 If someone does not wish to disclose information, that is their choice and it should be respected.

While this data collection standard is a step forward in collecting information from LGBTI communities, definitions used throughout the standard are based on current language and terminology, and it is important to keep in mind that these definitions will continue to change and evolve. Therefore, the terms used in the standard should be reviewed and updated over time to ensure they remain applicable and relevant.

This data collection standard provides information regarding inclusive language, and covers the following four data items:

- gender identity

- sex

- sexual orientation

- intersex

Although this data collection standard follows the approach of the Guidelines and the ABS Standard of collecting gender identity in preference to sex, information regarding sex has been included for several reasons, including the potential for improved data collection from transgender populations when combined with a gender identity question (also known as the two-step approach). Further information regarding the two-step approach is included under the gender identity and sex data items.

Using Inclusive language

The language that is used when talking to someone about their gender identity, sex, sexual orientation or intersex variation needs to be appropriate, sensitive and inclusive. Using inclusive language decreases the risk of misgendering a client, minimises harm, shows respect and has the ability to help build positive relationships with clients. From a data collection point of view, it is likely that the use of inclusive language increases the accuracy of the data collected.

Just as assumptions should be avoided regarding a person’s gender identity, sex, sexual orientation or intersex variation, it is important to avoid making assumptions about how someone wishes to be addressed and describes themselves. Whenever possible, questions should be asked privately to minimise discomfort or harm to a client.167

Names, pronouns and titles

A person’s name on identification documents, such as their driver’s license, may not match the name that they use. When a person discloses that they have a name that they use other than the name on their identification documents, an agency or service should ensure that they use this name when communicating with this person. Both the name that a person uses, and name/s on their official documentation, should be collected. See the ‘General data items’ section for information regarding the collection of name data.

Pronouns can imply someone’s gender, for example, describing someone as ‘he’ or ‘she’. People with non-binary genders often prefer pronouns that aren’t gendered, such as ‘they’. Some people prefer to be described with their first name only or may prefer no pronoun at all.168

Intersex people and transgender people who identify as women or men can feel excluded when

people avoid pronouns or use gender neutral language. Using inclusive language means referring to an intersex or transgender woman who identifies as a woman as ‘her’, ‘she’, or, ‘the woman’.169

Forms requiring a person to select a title should include ‘Mx’ as an option, which is used by some people with non-binary genders. Where possible, the inclusion of a free text option so that someone can self-describe is recommended. It is also important to know that some people do not use a title.

Inappropriate or offensive terms and language

The use of inappropriate language can make it difficult for LGBTI people to engage with services and can cause harm to LGBTI clients. If a person accidentally misgenders a client, or uses inappropriate language, apologise briefly and start using inclusive language.170 The below lists some examples of language and terms which should be avoided.

- Although intersex people may use a variety of terms to describe themselves, it is considered insensitive for others to describe intersex people as ‘hermaphrodites’ or as having ‘disorders of sex development’.171

- It is considered insensitive to assume that someone identifies as trans based on their history, or, to call some ‘a trans’ or ‘a transgender’.172

- Do not call an intersex woman or transgender woman ‘he’, ‘it’, ‘the person’, or avoid pronouns.

- Do not use the terms ‘preference’, ‘preferred’ and ‘lifestyle’ in relation to a person’s gender identity or sexual orientation. These terms suggest that a person’s identity is chosen, rather than who they are.

- Avoid language which assumes all relationships are heterosexual. It is better to use the word ‘partner’ than ‘wife/husband’ when the gender, sexual orientation or relationship status of a person is unknown. When someone mentions their children, do not make the assumption that the person is in a heterosexual relationship.173

For more information regarding inclusive language, see:

- Making your service intersex friendly, a guide created by Intersex Human Rights Australia, available on their website www.ihra.org.au/services

- Inclusive language guide: respecting people of intersex, trans and gender diverse experience, available on the National LGBTI Health Alliance website www.lgbtihealth.org.au

- Victorian Public Sector inclusive language guide, available at www.vic.gov.au/equality

- Policy and practice recommendations for alcohol and other drugs service providers supporting the trans and gender diverse community, available at www.vac.org.au

For information regarding some organisations which offer LGBTI inclusive training in Victoria, please refer to ‘Training and resources’.

Gender identity

In line with the Australian Government Guidelines on the Recognition of Sex and Gender (the Guidelines) and the ABS Standard, this data collection standard recommends collecting gender identity in preference to sex.

Definition

Gender refers to the socially constructed categories assigned on the basis of a person’s sex. While other genders are recognised in some cultures, in Western society, people are generally expected to conform to one of two gender roles matching their sex; male = man/masculine, and female = woman/feminine. Gender norms define how a person should dress and behave, and the roles people have in society.174 Gender identity refers to a person’s internal and individual sense of gender which is not always exclusively masculine or feminine, and may or may not correspond to their sex.175

Affirming one’s gender is a deeply personal decision that involves a person seeking to redress a mismatch between their assigned sex at birth and their gender identity. It does not necessarily involve surgery; it means that a person is living their affirmed gender.176

Question phrasing and response categories

|

What gender do you identify as? □ Male |

Standard answer categories

Gender diverse is an umbrella term which encompasses gender identities and expressions that are different from a person’s sex assigned at birth,177 and can include people who identify as transgender, agender (having no gender), bi-gender (both a woman and a man) or non-binary (neither woman nor man).178 Transgender (or trans) is a term used by some people who experience or identify their gender as not matching their sex assigned at birth.179 However, it is important to remember that not all gender diverse people are transgender,180 and many people of transgender experience live and identify as women or men, and may not have a ‘trans gender identity’.181 There is no one ‘correct’ or ‘complete’ way for trans and gender diverse people to express themselves.182

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people may use the terms Brotherboy and Sistergirl in a number of different contexts, however, they are used in some Aboriginal communities to refer to trans and gender diverse people.183 Sistergirls are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women who were classified male at birth but live their lives as women, including taking on traditional cultural female practices. Brotherboys are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men who were classified female at birth but live their lives as male.184 These communities may not identify with western transgender terminology,185 and western terms (for example, ‘Aboriginal transgender woman’) may be seen as insufficient due to the complex connection to culture that shapes these communities.186 When a Brotherboy or Sistergirl client answers a question about gender identity verbally, the data collector should ask which response category they feel best describes them, rather than making assumptions.

To collect data on gender diverse people, this framework uses the inclusive term of ‘self-described’ rather than ‘other’. As language used to describe gender identities is evolving, having broader terms will decrease the risk of this data item becoming outdated and no longer relevant. The inclusion of a ‘please specify’ free text option within the ‘self-described’ response option allows a person to selfidentify. It is acknowledged that some systems may not be able to practically accommodate free text, either due to software restrictions, or the lack of resourcing associated with coding free text. However, having this capability means that people may be more willing to respond, and, where possible and appropriate, would enable more detailed information which is useful for the refinement of data collection and understanding of clients. As some people may not be willing to self-disclose, the inclusion of a ‘prefer not to say’ response category is recommended.

It is acknowledged that ‘male’ and ‘female’ are terms used to describe biological sex rather than gender. However, these are the terms used in national standards. When standards (such as the ABS Standard) are revised, and if language used in such standards change, it will be necessary to review these response options. Research from the EHRC in the UK found that “despite concerns raised in focus groups around the potential confusion of using traditional sex categories when asking how one describes themselves (i.e. about gender), evidence from cognitive interviews suggests that the categories ‘male’ and ‘female’ do work, and they work well for both trans and non-trans individuals”.187

Sex

Although the framework follows the recommendation of the Guidelines and the ABS Standard regarding the collection of gender identity in preference to sex, information regarding sex has been included in the framework. Sex is still considered by many as a primary means of measuring and analysing many aspects of the population, and continues to be collected in the Census. It is also a key variable used in Statistical Linkage Keys (SLKs), which are relied on to identify unique individuals accessing services and link data between agencies and service providers.

It is important to note that it is not recommended that all agencies collect sex information. Sex should only be asked if there is an operational requirement for the agency. As previously noted, the purpose of collecting either sex or gender identity, or both, must be considered prior to collection.

Definition

Sex refers to the biological characteristics of a person, which include chromosomes, hormones and reproductive organs. Sex assigned at birth refers to the sex category assigned to a person when they were born. Although sex and gender are conceptually distinct, these terms are commonly used interchangeably, including in legislation.188

Question phrasing and response categories

|

What sex were you assigned at birth (i.e. what was specified on your original birth certificate)? □ Male |

Standard answer categories

In Victoria, currently only one sex (M or F) can be registered at birth. Changes may be made in the future to include another option at birth, and if this occurs in Victoria, this data item may need to be revised and an additional response category added.

Although there are current data collections that include response categories such as ‘indeterminate’, this is generally only a code that is used for infants aged less than 90 days. As previously noted, the Sex and Gender Advisory Group189 have stated that people whose bodily characteristics are not considered stereotypically female or male are not ‘indeterminate’ and often have clearly determined ways of categorising themselves.190

As previously noted in ‘Existing data standards’, most people with an intersex variation do not consider themselves to be a third sex. Thus, the inclusion of an ‘intersex’ response category is unlikely to accurately capture intersex populations, and a separate question is recommended to collect information from people with an intersex variation (see the ‘intersex’ data item on page 63 for more information).

As some people may not be willing to self-disclose, the inclusion of a ‘prefer not to say’ response category is recommended.

Trans-gender

There are many people of transgender experience who live and identify as women or men and may not have a ‘trans gender identity’. The two step approach, described below, has been identified as one means of enabling more trans and gender diverse people to be included in data sets. In addition, some DHHS data sets have included a transgender data item that more directly allows a person to identify themselves as transgender. As some people may not be willing to self-disclose, the inclusion of a ‘prefer not to say’ response category is recommended.

|

Do you identify as transgender? □ Yes |

| Two step approach to collecting sex and gender identity |

|---|

|

Most current research notes that the two step approach enables more trans and gender diverse people to be included in data.191, 192, 193, 194, 195, 196, 197 The two step approach is when a question regarding gender identity is used in conjunction with a question regarding sex. For example, if someone responds to a question regarding gender identity with ‘male’ and responds to a question regarding sex assigned at birth with ‘female’, this information might be used together to infer that this person should be included in the transgender population. Research undertaken regarding this approach has mostly been in the context of data collection via surveys, or health organisations collecting data in situations where asking sex has been operationally required. Thus, it is unclear if the two step approach is appropriate for the collection of administrative data in a family violence context. Additionally, asking a transgender person’s sex assigned at birth may trigger negative feelings. With the added vulnerability of a family violence situation, there may be risk in asking about a transgender person’s sex due to safety concerns. |

Considerations in asking gender identity, sex and transgender identity

Asking someone a question about their gender identity allows for responses that are not necessarily binary (female/male).198 People are more likely to respond affirmatively to questions that use language with which they are comfortable, and less likely to respond accurately to questions that misgender them.199

Gender identity can change over time, as can a person’s willingness to self-disclose. Information should continue to be collected, when appropriate, even if a person comes into repeat contact with a service, and it is recommended that there is the capability to change these fields in the data.

As previously mentioned, the purpose of collecting information from each data item in this framework needs to be made clear to the client, and information gained should be used to inform either a direct service response or referral to an appropriate service. Relevant privacy principles should always be considered when making the decision to collect sensitive information.

Sexual orientation

Definition

Sexual orientation encompasses several dimensions of sexuality including sexual identity, attraction and behavior,200 and refers to a person’s emotional, physical and/or sexual attraction to another person.201 The data being collected in this data item is most closely related to sexual identity, which is the self-identified label that a person may choose to describe themselves.202 As sexual identity is just one aspect of sexual orientation, this data item will not capture other aspects of sexual orientation (i.e. attraction and behaviour). For example, a man that identifies as straight but has sex with men.

Sexual orientation has been chosen as the term in this framework as it follows the work that has been done internationally in this space203 that most closely reflects the purpose of this framework. It is also a more familiar term to the broader community. It may be appropriate in the future to change terminology if questions on other aspects of sexuality become more widely understood.

Question phrasing and response categories

|

How would you describe your sexual orientation? □ Straight or heterosexual |

Standard answer categories

Definitions for the terms used as response categories are as follows:

- Straight/Heterosexual – a person who experiences attraction (romantic, sexual, affectional, and/or emotional) solely or primarily to people of the opposite sex and/or gender.

- Gay/Homosexual – a person who experiences attraction (romantic, sexual, affectional, and/or emotional) solely or primarily to people of the same sex and/or gender. Although it may be used by people of all sexes and/or genders, it is more commonly used by men.204

- Lesbian – a woman who experiences attraction (romantic, sexual, affectional, and/or emotional) solely or primarily to other women.205

- Bisexual or Pansexual – a person who experiences attraction (romantic, sexual, affectional, and/or emotional) to more than one gender.206 People who are pansexual may seek to express that gender does not factor into their own sexuality, or, that they are attracted to trans and gender diverse people who may or may not fit into the binary gender categories of male and female. This does not mean, however, that people who identify as bisexual are focused on traditional notions of gender.207

- Asexual – people who do not experience sexual attraction, although this does not preclude romantic attraction.

Note that gay, homosexual and lesbian have been grouped as the aim of this data item is to identify sexual orientation rather than gender. Although bisexual and pansexual are different sexual identities, they have been grouped due to the overlap that exists in their meaning.

As with the gender identity data item, the inclusion of a ‘please describe’ free text option is recommended, however it is acknowledged that some systems may not be able to accommodate free text, either due to software restrictions or the lack of resourcing associated with coding free text.

This data item includes a ‘don’t know’ option and, as some people may not be willing to self-disclose, the inclusion of a ‘prefer not to say’ response category is also recommended.

Considerations in asking sexual orientation

Unlike gender or sex, sexual orientation is not a question that is routinely asked of people in Australia. Research done by the LGBT Foundation in England indicated that 90-95% of people would be comfortable disclosing their sexual orientation as part of demographic data collection if they understood why it was being collected.208 In preparation for their 2021 Census, the ONS in the United Kingdom tested the inclusion of a sexual identity question and evidence suggests the question is broadly acceptable and will not have a significant impact on overall response. Although the context of a census is different to the context of this framework, it is worth noting these findings.

NHS England, in collaboration with the LGBT Foundation, created their question set for sexual orientation based on research conducted by the ONS and the EHRC, and on current practice by organisations which collect data on sexual orientation. This has helped to inform the creation of the sexual orientation data item in this framework. Their standard covers all adults (i.e. those aged 16 and over) and although this standard is closely aligned with the NHS standard, it does not dictate the age at which this question should be asked by an organisation. As noted at the beginning of the data collection standard, organisational change and staff training is vital to ensure sexual orientation can be collected in the appropriate context, in an inclusive and sensitive way.

As the sexual orientation people identify with can change over time, as can a person’s willingness to self-disclose, information should continue to be collected even if a person comes into repeat contact with a service. Thus, there should be the capability to change this data field over time.

Intersex

Definition

Intersex people are born with sex characteristics that do not fit medical norms for female or male bodies.209 These characteristics can be physical, hormonal or genetic. Many forms of intersex exist, with more than 40 different variations known. Intersex variations may be apparent at birth or diagnosed prenatally. Some intersex traits become apparent at puberty, or when trying to conceive, or through random chance.210

Question phrasing and response categories

Intersex is a term for people born with atypical physical sex characteristics, and there are many different intersex traits or variations.

| Do you have an intersex variation? □ Yes □ No □ Prefer not to say |

Intersex people have a diversity of sex characteristics and gender identities. Most intersex people identify their sex as male or female, and do not wish to be considered a third sex.211 Thus, adding an ‘intersex’ category to a question regarding sex or gender identity is not appropriate, and a separate question is required to collect data from intersex populations. Separating intersex from a question on sex and/or gender avoids misgendering people with intersex variations and inadvertently including people who mistake intersex for a gender identity.212

It should not be assumed that respondents will understand what is meant by the term intersex, and it is recommended that the short descriptive statement preceding the question ‘Do you have an intersex variation?’ is used.

As some people may not be willing to self-disclose, the inclusion of a ‘prefer not to say’ response category is recommended. Additionally, it is recommended that only one response is accepted for this data item.

Training and resources

In order for organisations to be able to sensitively collect data from LGBTI people in the appropriate contexts, organisations need to ensure that their policies and procedures are inclusive of LGBTI people, and staff must be trained in practice which is LGBTI inclusive. The list of organisations below is not exhaustive, but seeks to provide some valuable resources for agencies and service providers in Victoria. Please note that many of the organisations listed are not-for-profit, with limited funding available for the services they provide. Thus, the training noted here may not be available on an ongoing basis. The information below is sourced from the websites of the organisations listed, and the National LGBTI Health Alliance’s professional development, education and training list, https://www.lgbtiqhealth.org.au/member_training_courses.

Training

Gay and Lesbian Health Victoria

GLHV offers a range of training options aimed at improving the quality of services organisations provide to LGBTI people. For more information, visit www.glhv.org.au/training or phone 03 9479 8760. Available training includes:

- Living LGBTI – a half-day training session which explores the ways in which discrimination affects the health and wellbeing of LGBTI people’s everyday lives.

- LGBTI diversity in aged care – a one day training session which promotes awareness of the range of issues facing older LGBTI people, provides information about relevant policy and legal issues, and focuses on inclusive care for LGBTI clients and residents.

- HOW2 Program – four workshops run over six months which promote the development of LGBTI-inclusive health and human services and assists organisations in the implementation of practices, protocols and procedures. The HOW2 program is based on a set of six ‘Rainbow Tick’ national standards for health and human services which were developed by GLHV in conjunction with Quality Innovation Performance (QIP). It is important to note that although the program is based on these standards, completion of the HOW2 program does not result in the awarding of a Rainbow Tick. In order for an organisation to obtain the Rainbow Tick, it must be formally accredited through an external process undertaken by QIP.

For more information, visit https://www.qip.com.au/standards/rainbow-tick-standards/.

Intersex Human Rights Australia (formerly known as OII Australia)

IHRA is a national not-for-profit organisation promoting human rights for intersex people, and provides information, education, and support. IHRA can offer custom training and education, which includes advice on the impact of legislation and regulations, human resources and equal opportunity issues. For further information, visit www.ihra.org.au/services.

Minus18

Based in Melbourne, Minus18 is Australia’s largest youth-led organisation for LGBTI youth. Minus18 offer 60-90 minute training sessions, with content which can be tailored to an organisation’s needs. For more information, visit www.minus18.org.au/index.php/workshops/adult-professional-training. Current available training includes:

- Sexuality and gender – explores issues affecting LGBTI youth, and equips attendees with tools to build LGBTI inclusivity into an organisation

- Supporting trans and gender diverse youth – provides an in-depth understanding of the issues trans and gender diverse youth face, with guidance to create supportive working solutions such as policy and procedure updates

Pride Inclusion Programs

Pride Inclusion Programs are social inclusion initiatives of ACON. Pride in Diversity is a national notfor- profit employer support program for LGBTI workplace inclusion specialising in HR, organisational change and workplace diversity, and Pride in Health and Wellbeing is a national membership program that provides year-round support in the provision of LGBTI inclusive services for those working within the health and wellbeing sector. For more information visit www.prideinclusionprograms.com.au and www.acontraining.org.au.

Transgender Victoria

Transgender Victoria (TGV) educates organisations and workplaces on how to provide better services for trans and gender diverse people, and seeks ways to provide direct services to these communities. For more information, visit www.transgendervictoria.com or phone 03 9020 4642. Current available training includes:

- LGBTI training – a 3 hour session which explores LGBTI inclusive practice, and differences between sexual orientation, gender identity and people with intersex characteristics.

- Trans and gender diverse introduction – a 2-3 hour session which covers areas of disadvantage and discrimination for trans and gender diverse people and related mental health impacts, legislative obligations, and provides suggestions/tips on working with trans and gender diverse people.

- LGBTI aged care sector training – a 3 hour session in LGBTI inclusive ageing and aged care training for all people involved in the aged care sector, providing attendees with more confidence to deliver inclusive, best practice service.

Thorne Harbour Health

Thorne Harbour Health (THH, previously known as the Victorian AIDS Council) advocate to improve health outcomes for sexually and gender diverse people, and have 35 years of experience working with these communities. THH run the only Men’s Behaviour Change Program for gay, bisexual, and queer men (including transgender men), and offer flexible support packages for LGBTI people experiencing family violence.

THH Education and Training aims to develop the workforce, improve sector capacity and increase awareness of the unique and complex vulnerabilities in LGBTI communities. THH training promotes a safe learning environment to enable useful discussions and interactions to take place between participants and facilitators. Education and training areas include:

- LGBTI cultural competency and sensitivity

- trans and gender diverse cultural competency and sensitivity

- family and intimate partner violence within LGBTI communities

- alcohol and drug use within LGBTI communities

- mental health and LGBTI communities

- sexual health and LGBTI communities

For more information, visit https://thorneharbour.org or phone 03 9865 6700.

Zoe Belle Gender Collective

The Zoe Belle Gender Collective are an online not-for-profit organisation which provides support, training and resources for Victorian trans and gender diverse communities. The youth project officer, Starlady, offers training which gives an introduction to trans and gender diverse youth inclusive practice which ranges between 1 and 3 hours. For further information, visit www.zbgc.com.au/transgender-gender-diverse-youth-training/ or phone 03 9448 6141.

Other resources

The below lists websites that contain a variety of information regarding LGBTI communities, and many offer valuable services to these communities and the wider population.

Please note that the organisations which offer training, listed above under ‘Training’, also have a vast amount of information available on their websites.

Anti-Violence Project Victoria

Victoria’s Anti-Violence Project are a not-for-profit organisation leading discussion on violence and its impacts on LGBT people and intersex people who identify with the sexually and gender diverse community. Anti-Violence Project provide an online portal for those wishing to report violence, and liaise with Victoria Police and other agencies to assist victims.

Website: www.antiviolence.info

Bisexual Alliance Victoria

Bisexual Alliance Victoria Inc. is a non-profit volunteer-run organisation dedicated to promoting the acceptance of bisexuals in LGBTI and mainstream society, providing a fun, safe space where bisexuals can meet, make friends, and talk about their experiences, and informing the bisexual community about relevant news and opportunities for activism.

Website: www.bi-alliance.org

Melbourne Bisexual Network

The Melbourne Bisexual Network aims to raise awareness around the unique health and wellbeing issues that face people who are multi-gender attracted, and to collectively determine strategies to improve and promote bi-inclusivity in LGBTQIA+ programs and services.

Website: www.melbournebisexualnetwork.com

National LGBTI Health Alliance

The National LGBTI Health Alliance is the national peak health organisation in Australia for organisations and individuals that provide health-related programs, services and research focused on LGBTI people. Much of the information produced by the National LGBTI Health Alliance has been referenced throughout this section, and is available on their website.

Website: www.lgbtihealth.org.au

The Fenway Institute – Do ask, do tell

A US-based toolkit for collecting data on sexual orientation and gender identity in clinical settings.

Website: www.doaskdotell.org

US National LGBTI Health Education Center

This website features useful webinars, including collecting data on sexual orientation and gender identity in the electronic health record: why and how.

Website: www.lgbtihealtheducation.org/training/on-demand-webinars

queerspace (located at Drummond Street Services)

queerspace is an LGBTI health and wellbeing support service with a focus on relationships, families, parenting and young people. queerspace services deliver counselling and case management for a range of issues, including intimate partner and family violence.

Website: www.queerspace.org.au/

Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission

The Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission (VEOHRC) is an independent statutory body with responsibilities under the Equal Opportunity Act 2010 (Vic), Racial and Religious Tolerance Act 2011 (Vic), and the Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities, and they provide information pertinent to these three laws. VEOHRC also provide a free phone enquiry line and free dispute resolution services. Their website contains a variety of information, including guidelines for family violence services and accommodation, and for transgender people at work.

Website: www.humanrightscommission.vic.gov.au

Glossary

This glossary is based on the format of the LGBTIQ+ communities glossary created by the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) Child Family Community Australia,213 in that terminology is organised into the following categories:

- bodies and gender

- sexual orientation

- societal attitudes and issues

A range of sources have been used which contain further terminology and information, which include the LGBTIQ+ communities glossary noted above as well as the following:

- Inclusive language guide: Respecting people of intersex, trans and gender diverse experience (National LGBTI Health Alliance).214

- Addressing sexual orientation and sex and/or gender identity discrimination: Consultation Report (Australian Human Rights Commission).215

- LGBTI Data: Developing an evidence-informed environment for LGBTI health policy (National LGBTI Health Alliance).216

- Trans Pathways: the mental health experiences and care pathways of trans young people (Telethon Kids Institute Australia).217

- Guideline: Transgender people at work – Complying with the Equal Opportunity Act 2010 in Employment (VEOHRC).218

- From Blues to Rainbows: Mental health and wellbeing of gender diverse and transgender young people in Australia (ARCSHS, La Trobe University).219

- Making your service intersex friendly (IHRA and ACON).220

- LGBTI people and communities (LGBTI Health Alliance).221

- Transgender Victoria definitions.222

- Transcend support terminology and inclusive language.223

- Rainbow eQuality guide definitions (Department of Health and Human Services).224

- Bisexual Alliance Victoria Inc website.225

- Sexuality and gender terms (University of WA).226

- Intersex Human Rights Australia (IHRA) website.227

Definitions used are based on current language and terminology, and it is important to keep in mind that these definitions will continue to change and evolve. This glossary contains many key terms, but is not an exhaustive list of all terms that are used to describe gender, sex, sexual orientation and intersex.

Bodies and gender

Gender – refers to the socially constructed categories assigned on the basis of a person’s sex. While other genders are recognised in some cultures, in Western society, people are expected to conform to one of two gender roles matching their sex; male = man/masculine, and female = woman/feminine.

Gender binary – the classification of gender into two categories of man/woman.

Gender norms – relate to how a person should dress and behave, and the roles people have in society.

Gender identity – refers to a person’s internal and individual sense of gender which is not always exclusively masculine or feminine, and may or may not correspond to their sex.

Gender diverse – a term which encompasses all gender identities and expressions that are different from a person’s sex assigned at birth. Includes people who identify as agender (having no gender), as bi-gender (both a woman and a man) or as non-binary (neither woman nor man), and some nonbinary people identify as genderqueer or as having fluid genders.

Transgender or Trans – a person whose gender identity does not align with their sex assigned at birth. Trans is an umbrella term that includes a wide variety of identities. Not everyone who falls under this umbrella refers to themselves as ‘trans’. For example, while some women who have transitioned or affirmed their gender may refer to themselves as trans women, others may simply refer to themselves as women, and others will use a variety of terms. There is no one ‘correct’ or ‘complete’ way for people to express themselves.

Transsexual – a person who identifies as a member of the ‘opposite’ sex (ie. other than their birth sex) who usually seeks hormone therapy and often surgery to bring their body into line with their gender identity. Transsexual is an older term, and unlike transgender, is not an umbrella term. Many transgender people do not identify as transsexual.

Transgender female or Trans woman – a person who was assigned male at birth who identifies as female/woman.

Transgender male or Trans man – a person who was assigned female at birth who identifies as a male/man.

Brotherboy – Brotherboy and Sistergirl are terms used by transgender people within some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. Brotherboys are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men who were classified female at birth but live their lives as men.

Sistergirl – Brotherboy and Sistergirl are terms used by transgender people within some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. Sistergirls are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women who were classified male at birth but live their lives as women, including taking on traditional cultural female practices.

Affirming gender – a personal decision that involves a person seeking to redress a mismatch between their sex assigned at birth and their gender identity. A person living in their affirmed gender does not necessarily involve surgery.

Misgendering – a term for describing or addressing someone using language that does not match how that person identifies their own gender or body. For example, using the pronoun ‘he’ instead of ‘she’ to describe a trans woman.

Cisgender – a person who identifies with their sex assigned at birth.

Sex – refers to the biological characteristics of a person, which include chromosomes, hormones and reproductive organs.

Sex assigned at birth – refers to the sex category assigned to a person when they were born.

Gender diverse – a term which encompasses all gender identities and expressions that are different from a person’s sex assigned at birth. Includes people who identify as agender (having no gender), as bi-gender (both a woman and a man) or as non-binary (neither woman nor man), and some nonbinary people identify as genderqueer or as having fluid genders.

Transgender or Trans – a person whose gender identity does not align with their sex assigned at birth. Trans is an umbrella term that includes a wide variety of identities. Not everyone who falls under this umbrella refers to themselves as ‘trans’. For example, while some women who have transitioned or affirmed their gender may refer to themselves as trans women, others may simply refer to themselves as women, and others will use a variety of terms. There is no one ‘correct’ or ‘complete’ way for people to express themselves.

Transsexual – a person who identifies as a member of the ‘opposite’ sex (ie. other than their birth sex) who usually seeks hormone therapy and often surgery to bring their body into line with their gender identity. Transsexual is an older term, and unlike transgender, is not an umbrella term. Many transgender people do not identify as transsexual.

Transgender female or Trans woman – a person who was assigned male at birth who identifies as a female/woman.

Transgender male or Trans man – a person who was assigned female at birth who identifies as a male/man.

Brotherboy – Brotherboy and Sistergirl are terms used by transgender people within some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. Brotherboys are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men who were classified female at birth but live their lives as men.

Sistergirl – Brotherboy and Sistergirl are terms used by transgender people within some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. Sistergirls are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women who were classified male at birth but live their lives as women, including taking on traditional cultural female practices.

Affirming gender – a personal decision that involves a person seeking to redress a mismatch between their sex assigned at birth and their gender identity. A person living in their affirmed gender does not necessarily involve surgery.

Misgendering – a term for describing or addressing someone using language that does not match how that person identifies their own gender or body. For example, using the pronoun ‘he’ instead of ‘she’ to describe a trans woman.

Cisgender – a person who identifies with their sex assigned at birth.

Sex – refers to the biological characteristics of a person, which include chromosomes, hormones and reproductive organs.

Sex assigned at birth – refers to the sex category assigned to a person when they were born.

Intersex – people who are born with sex characteristics that don’t fit medical norms for female or male bodies. These characteristics can be physical, hormonal or genetic. People may describe themselves as intersex, or as having an intersex variation.

Sexual orientation

Sexual orientation – encompasses several dimensions of sexuality including sexual identity, attraction and behaviour, and refers to a person’s emotional, physical and/or sexual attraction to another person.

Sexual identity – self-identified label that a person may choose to describe themselves. For example, gay, lesbian or bisexual.

Gay/Homosexual – a person who experiences attraction (romantic, sexual, affectional, and/or emotional) solely or primarily to people of the same gender. Although it may be used by people of all genders, it is more commonly used by men.

Lesbian – a woman who experiences attraction (romantic, sexual, affectional, and/or emotional) solely or primarily to other women.

Bisexual/Pansexual – a person who experiences attraction (romantic, sexual, affectional, and/or emotional) to more than one gender. People who are pansexual may seek to express that gender does not factor into their own sexuality, or, that they are specifically attracted to trans, genderqueer, and other people who may or may not fit into the binary gender categories of male and female. This does not mean, however, that people who identify as bisexual are fixated on traditional notions of gender.

Queer – a term used by some people whose identity is not adequately described by existing categories or labels (such as lesbian, gay, or bisexual). It also extends outside of sexual orientation in that it is sometimes used as an umbrella term to include the diversity of sexual and/or gender identities in LGBTI communities. Some people prefer not to use this term as the history of the word has negative connotations, but in more recent times, the term has been reclaimed as a symbol of pride.

Asexual – people who do not experience sexual attraction, although this does not preclude romantic attraction.

Societal attitudes and issues

Biphobia – negative beliefs, prejudices and stereotypes that exist about people who are bisexual.

Homophobia – negative beliefs, prejudices and stereotypes that exist about people who are homosexual.

Intersexphobia or Interphobia – negative beliefs, prejudices and stereotypes that exist about intersex people.

Transphobia – negative beliefs, prejudices and stereotypes that exist about trans and gender diverse people.

Outing – threatening to disclose someone’s gender identity, sex, sexual orientation or intersex variation.

132 RCFV 2016, Volume 5 Report and recommendations, p.141.

133 Ibid.

134 Trans and gender diverse definition source, Transgender Victoria. Intersex definition source, Intersex Human Rights Australia. It is important to note that intersex is not a third sex (White paper – Making the Count: Addressing data integrity gaps in Australian standards for collecting sex and gender information, National LGBTI Health Alliance, 2016).

135 RCFV 2016, Volume 5 Report and recommendations, p.143.

136 Ibid p.144.

137 ANROWS 2014, Violence against women: Key statistics, viewed 22 June 2018, www.anrows.org.au/publications/fast-facts-0/violence-against-women-key-statistics

138 US National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs 2018, Community Action Toolkit for Addressing Intimate Partner Violence Against Transgender People, viewed 20 June 2018, https://avp.org/ncavp/ncavp-toolkits/

139 Barking and Dagenham NHS 2008, Domestic Violence: A resource for gay & bisexual men, viewed 20 June 2018,

www.domesticviolencelondon.nhs.uk/uploads/downloads/DV-Resource_for_Gay_Men.pdf

140 RCFV 2016, Volume 5 Report and recommendations, p.154.

141 Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission (VEOHRC) 2015, Submission to the Royal Commission into Family Violence, no. 609, p.17, viewed 22 June 2018, www.rcfv.com.au/Submission-Review

142 Gay and Lesbian Health Victoria, Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health & Society, La Trobe University 2015, Family Violence and the LGBTI Community: Submission to the Victorian Royal Commission into Family Violence, no. 821, viewed 22 June 2018, www.rcfv.com.au/Submission-Review

143 No To Violence and safe steps Family Violence Response Centre 2015, safe steps Family Violence Response Centre and No To Violence joint submission: Family Violence and LGBTIQ Communities, no. 933, viewed 22 June 2018, www.rcfv.com.au/Submission-Review

144 Irlam, C B 2012, LGBTI Data: Developing an evidence-informed environment for LGBTI public policy, National LGBTI Health Alliance, Sydney.

145 No To Violence and safe steps Family Violence Response Centre 2015, safe steps Family Violence Response Centre and No To Violence joint submission: Family Violence and LGBTIQ Communities, no. 933, viewed 22 June 2018, www.rcfv.com.au/Submission-Review

146 Irlam, C B 2012, LGBTI Data: Developing an evidence-informed environment for LGBTI public policy, National LGBTI Health Alliance, Sydney.

147 RCFV 2016, Volume 5 Report and recommendations, p.142.

148 Irlam, C B 2012, LGBTI Data: Developing an evidence-informed environment for LGBTI public policy, National LGBTI Health Alliance, Sydney.

149 Attorney-General’s Department 2015, Australian Government Guidelines on the Recognition of Sex and Gender, viewed 20 June

2018, www.ag.gov.au/Publications/Pages/AustralianGovernmentGuidelinesontheRecognitionofSexandGender.aspx

150 Ibid.

151 ABS 2016, 1200.0.55.012 Standard for Sex and Gender Variables, 2016, viewed 20 June 2018,

www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/latestProducts/1200.0.55.012Media%20Release12016

152 Ansara, Y G 2016, Making the Count: Addressing data integrity gaps in Australian standards for collecting sex and gender information [White paper], National LGBTI Health Alliance, Newtown.

153 Ibid.

154 ABS 2016, 1200.0.55.012 Standard for Sex and Gender Variables, 2016, viewed 20 June 2018, www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/latestProducts/1200.0.55.012Media%20Release12016

155 The Sex and Gender Advisory Group consists of members from five Australian organisations; National LGBTI Health Alliance, A Gender Agenda, Intersex Human Rights Australia (formerly known as Organisation Intersex International Australia), Transformative and Transgender Victoria.

156 Ansara, Y G, Webeck, S, Carpenter, M, Hyndal, P & Goldner, S 2015, Re Commonwealth Attorney-General’s Department Review of the Australian Government Guidelines on the Recognition of Sex and Gender, LGBTI Health Alliance, Sydney.

157 Ibid.

158 Ansara, Y G 2016, Making the Count: Addressing data integrity gaps in Australian standards for collecting sex and gender information [White paper], National LGBTI Health Alliance, Newtown.

159 Statistics New Zealand 2015, Gender identity, viewed 20 June 2018, archive.stats.govt.nz/methods/classifications-andstandards/

classification-related-stats-standards/gender-identity.aspx

160 UK Office for National Statistics 2017, Gender identity update, viewed 20 June 2018, www.ons.gov.uk/methodology/classificationsandstandards/measuringequality/genderidentity/genderidentityupdate

161 ABS 2015, 4159.0 General Social Survey: Summary Results, Australia, 2014, viewed 20 June 2018, abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/4159.0

162 Rainbow Health Ontario 2012, LGBTQ Research with Secondary Data [Fact Sheet], viewed 20 June 2018,

www.rainbowhealthontario.ca/resources/rho-fact-sheet-lgbt-research-with-secondary-data/

163 LGBT Foundation and NHS England 2017, Sexual Orientation Monitoring: Full Specification, viewed 20 June 2018,

www.england.nhs.uk/publication/sexual-orientation-monitoring-full-specification/

164 Ibid.

165 Misgendering is a term for describing or addressing someone using language that does not match how that person identifies their own gender or body. For example, using the pronoun ‘he’ instead of ‘she’ to describe a trans woman.

166 Gay and Lesbian Health Victoria, Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health and Society and La Trobe University 2016, The Rainbow Tick Guide to LGBTI-inclusive practice, La Trobe University, Melbourne.

167 Ansara, Y G, 2013, Inclusive Language Guide: Respecting people of intersex, trans and gender diverse experience, National LGBTI Health Alliance, Newtown.

168 State Government of Victoria 2016, Inclusive Language Guide, viewed 20 June 2018, https://www.vic.gov.au/equality/inclusivelanguage-guide.html

169 Ansara, Y G, 2013, Inclusive Language Guide: Respecting people of intersex, trans and gender diverse experience, National LGBTI Health Alliance, Newtown.

170 Ibid.

171 Ibid.

172 Ibid.

173 State Government of Victoria 2016, Inclusive Language Guide, viewed 20 June 2018, https://www.vic.gov.au/equality/inclusivelanguage-guide.html

174 AIFS 2017, LGBTIQ+ communities: Glossary of common terms, viewed 20 June 2018, https://aifs.gov.au/cfca/publications/lgbtiqcommunities

175 Australian Human Rights Commission 2011, Addressing sexual orientation and sex and/or gender identity discrimination: Consultation Report, viewed 20 June 2018, www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/sexual-orientation-sex-gender-identity/publications/addressingsexual-

orientation-and-sex

176 VEOHRC 2014, Guideline: Transgender people at work – Complying with the Equal Opportunity Act 2010 in Employment, viewed 20 June 2018, www.humanrightscommission.vic.gov.au/our-resources-and-publications/eoa-practice-guidelines/item/632-guidelinetransgender-people-at-work-complying-with-the-equal-opportunity-act-2010

177 Strauss, P, Cook, A, Winter, S, Watson, V, Wright Toussaint, D & Lin, A 2017, Trans Pathways: the mental health experiences and

care pathways of trans young people, Telethon Kids Institute Australia, Perth.

178 Ansara, Y G, 2013, Inclusive Language Guide: Respecting people of intersex, trans and gender diverse experience, National LGBTI Health Alliance, Newtown.

179 Strauss, P, Cook, A, Winter, S, Watson, V, Wright Toussaint, D & Lin, A 2017, Trans Pathways: the mental health experiences and

care pathways of trans young people, Telethon Kids Institute Australia, Perth.

180 Transcend 2018, Terminology & Inclusive Language, viewed 20 June 2018, www.transcendsupport.com.au/terminology-inclusivelanguage/

181 National LGBTI Health Alliance 2016, National Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex Mental Health and Suicide

Prevention Strategy: A new strategy for inclusion and action, viewed 20 June 2018, lgbtihealth.org.au/wpcontent/uploads/2016/12/LGBTI_Report_MentalHealthandSuicidePrevention_Final_Low-Res-WEB.pdf

182 Transgender Victoria 2013, About TGV, viewed 20 June 2018, www.transgendervictoria.com/about.

183 Transcend 2018, Terminology & Inclusive Language, viewed 20 June 2018, www.transcendsupport.com.au/terminology-inclusivelanguage/

184 AIFS 2017, LGBTIQ+ communities: Glossary of common terms, viewed 20 June 2018, https://aifs.gov.au/cfca/publications/lgbtiqcommunities

185 Queensland Association for Healthy Communities Inc 2008, Supporting transgender and sistergirl clients: Providing respectful and inclusive services to transgender and sistergirl clients, viewed 20 June 2018, www.rainbowhealthontario.ca/resources/supportingtransgender-and-sistergirl-clients-providing-respectful-and-inclusive-services-to-transgender-and-sistergirl-clients/

186 Toone K, Sistergirls and the impact of community and family on wellbeing, honours thesis, Flinders University, Adelaide, viewed 20 June 2018, http://www.flinders.edu.au/

187 Balarajan, M, Gray, M & Mitchell, M 2011, Monitoring equality: Developing a gender identity question [Research Report], Equality and Human Rights Commission UK, Manchester.

188 Attorney-General’s Department 2015, Australian Government Guidelines on the Recognition of Sex and Gender, viewed 20 June

2018, www.ag.gov.au/Publications/Pages/AustralianGovernmentGuidelinesontheRecognitionofSexandGender.aspx

189 The Sex and Gender Advisory Group consists of members from five Australian organisations; National LGBTI Health Alliance, A Gender Agenda, Organisation Intersex International Australia, Transformative and Transgender Victoria.

190 Ansara, Y G, Webeck, S, Carpenter, M, Hyndal, P & Goldner, S 2015, Re Commonwealth Attorney-General’s Department Review of the Australian Government Guidelines on the Recognition of Sex and Gender, LGBTI Health Alliance, Sydney.

191 The Gender Identity in U.S. Surveillance Group 2014, Best Practices for Asking Questions to Identify Transgender and Other Gender Minority Respondents on Population-Based Surveys, the Williams Institute, Los Angeles.

192 Center of Excellence for Transgender HIV Prevention 2009, Recommendations for Inclusive Data Collection of Trans People in HIV Prevention, Care & Services, University of California, San Francisco.

193 Balarajan, M, Gray, M & Mitchell, M 2011, Monitoring equality: Developing a gender identity question [Research Report], Equality and Human Rights Commission UK, Manchester.

194 Peer Advocacy Network for the Sexual Health of Trans Masculinities 2017, Position Statement: Data Collection, viewed 20 June 2018, www.grunt.org.au/wp-content/uploads/PASH.tm-Data-Collection_Nov_2017.pdf

195 Cahill, S, Singal, R, Grasso, C, King, D, Mayer, K, Baker, K & Makadon, H 2014, ‘Do Ask, Do Tell: High Levels of Acceptability by Patients of Routine Collection of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Data in Four Diverse American Community Health Centers’, PLoS ONE, vol. 9, no. 9.

196 National LGBT Health Education Center, The Fenway Institute 2016, Collecting Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Data in

Electronic Health Records: Taking the Next Steps, viewed 20 June 2018, http://www.lgbthealtheducation.org/wpcontent/