- Published by:

- Family Safety Victoria

- Date:

- 2 Dec 2019

The Victorian Government proudly acknowledges Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as the first peoples and Traditional Owners and custodians of the land. We pay respect to Elders, past and present, and acknowledge the ongoing leadership role of the Aboriginal community in addressing and preventing family violence. We would like to acknowledge and thank all stakeholders for their time and their ideas which have contributed to the development of the Victorian Family Violence Data Collection Framework.

Unless indicated otherwise, content in this publication is provided under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence. To view a copy of this licence, visit creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. It is a condition of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Licence that you must give credit to the original author who is the State of Victoria.

Data Item Reference Guide

Lists each data item in the framework and which section it can be found in.

The table below lists each data item in the framework and the section it can be found in.

| Section | Data item |

|---|---|

| General data items | Names |

| General data items | Age and date of birth |

| General data items | Date variables |

| General data items | Geographic variables (including person address and organisation address) |

| General data items | Unique identifiers |

| General data items | Data linkage |

| Family violence data items | Types of family violence |

| Family violence data items | Relationship between parties |

| Family violence data items | Role of party |

| LGBTI communities | Gender identity |

| LGBTI communities | Sex |

| LGBTI communities | Sexual orientation |

| LGBTI communities | Intersex |

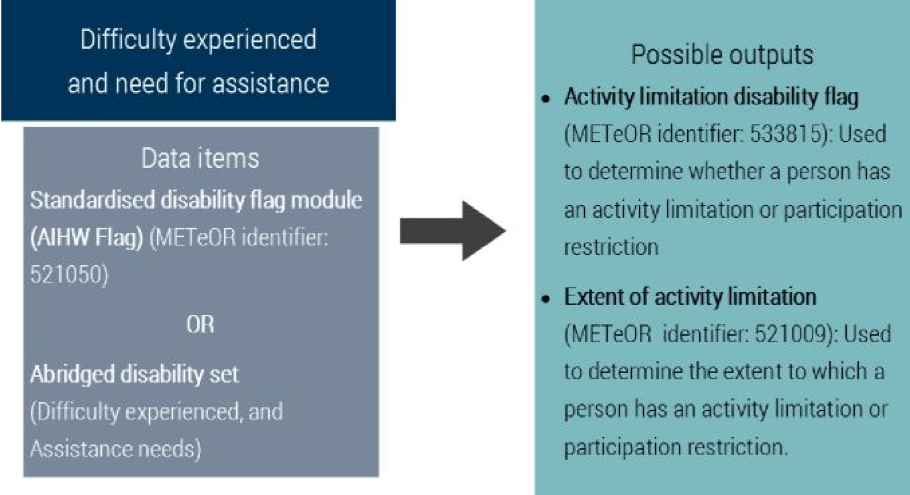

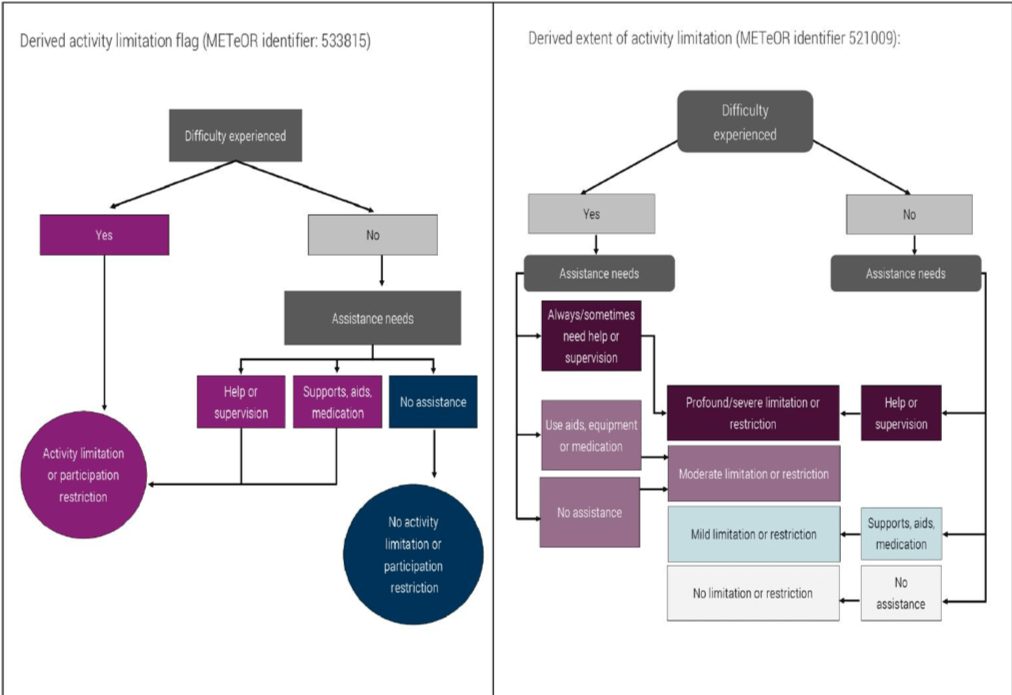

| People with disabilities | Standardised disability flag |

| People with disabilities | Abridged disability set (difficulty experienced, assistance needs) |

| People with disabilities | Disability group |

| People with disabilities | Reasonable adjustments |

| CALD communities | Country of birth |

| CALD communities | Cultural background and ethnicity |

| CALD communities | Main language spoken at home |

| CALD communities | Interpreter required |

| Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities | Standard Indigenous Question |

Acronyms and terminology

Lists acronyms and terminology used throughout this publication.

Acronyms

ABS: Australian Bureau of Statistics

ACCO: Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisation

AFM: Affected family member

AFVITH: Adolescent family violence in the home

AIFS: Australian Institute of Family Studies

AIHW: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare

ANROWS: Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety

ASCCEG: Australian Standard Classification of Cultural and Ethnic Groups

ASCL: Australian Standard Classification of Languages

CALD: Culturally and linguistically diverse

CSA: Crime Statistics Agency

CVS: Crime Victimisation Survey

DCRF: Foundation for a National Data Collection and Reporting Framework for family, domestic and sexual violence

DHHS: Department of Health and Human Services

DPC: Department of Premier and Cabinet

EHRC: Equality and Human Rights Commission UK

FVDB: Victorian Family Violence Database

FVPA: Family Violence Protection Act 2008 (Vic)

HPP: Health Privacy Principles

HRA: Health Records Act 2001 (Vic)

IPP: Information Privacy Principles

IRIS: Integrated Reports and Information System

L17: Victoria Police Family Violence Risk Assessment and Management form

LEAP: Victoria Police Law Enforcement Assistance Program

LGBTI: Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex

METeOR: Metadata Online Registry

NATSISS: National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey

NCIS: National Coronial Information System

NDIS: National Disability Insurance Scheme

NHS: National Health Service England

NTV: No to Violence

ONS: Office for National Statistics UK

PDPA: Privacy and Data Protection Act 2014 (Vic)

PSS: Personal Safety Survey

RCFV: Royal Commission into Family Violence

SACC: Standard Australian Classification of Countries

SDAC: Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers

SDS: Supplementary Disability Survey

SIQ: Standard Indigenous Question

SLK: Statistical linkage key

UID: Unique identifier

VEOHRC: Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission

VPDSF: Victorian Protective Data Security Framework

Terminology

A glossary appears at the end of each priority community section of this framework which includes definitions specific to each particular section. However, broader terminology which is used throughout the framework is discussed here and is based on language used by the Royal Commission into Family Violence (RCFV).1

Family violence

‘Family violence’ is the term used throughout this framework to refer to a wide range of behaviours identified in the Family Violence Protection Act 2008 (Vic). Information regarding the definition of family violence can be found on page 26. Where this framework directly references materials which use other terms such as ‘domestic violence’ or ‘intimate partner violence’, these terms have been retained, however the scope of these terms is typically more narrow than family violence. Domestic violence may be used to refer to acts of violence between intimate partners and violence in the context of family relationships. It may be used in legislation in other jurisdictions and in practice guidance in some parts of Victoria. Intimate partner violence is commonly used to highlight the predominant manifestation of the violence, which is in the context of current or former intimate partner relationships.

Language about victims

State and national policy and non-government services primarily use the terms ‘victim’, ‘victimsurvivor’ to refer to adults and children who have experienced family violence, as well as ‘woman and their children who experience violence’. The Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme under Part 5A of the Family Violence Protection Act 2008 (Vic) uses the term ‘primary person’ to describe a person about whom there is a reasonable belief there is a risk they may be subjected to family violence. Victoria Police use the term ‘affected family member’ in the context of police attended or reported family violence incidents. In the context of intervention order applications, courts also use the term ‘affected family member’, and use ‘applicant’ to describe the person applying for an order. ‘Victim’ is sometimes considered problematic because it suggests that people who have experienced family violence are helpless or lack the capacity to make rational choices about how to respond to the violence. For the purposes of the framework, the terms ‘victim’, ‘victim-survivor’ and ‘people who experience violence’ (or ‘people who experience abuse’) are used interchangeably, unless referencing material which uses other terms, or specifically discussing information within the context of Victoria Police or courts.

Language about perpetrators

A broad range of terminology is used in relation to people who use violence, including ‘perpetrators’ and ‘men who use violence’. The Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme under Part 5A of the Family Violence Protection Act 2008 (Vic) uses the term ‘person of concern’ to describe a person that there is a reasonable belief there is a risk they may commit family violence. Victoria Police use the term ‘respondent’ to refer to a person described as using violence in the context of police attended or reported family violence incidents. The word ‘defendant’ may be used to describe a person being prosecuted for a family violence offence, and the word ‘offender’ may be used to describe a person who has been found guilty of such an offence. For the purposes of the framework, the terms ‘people who use violence’ and ‘perpetrator’ are used interchangeably.

Priority communities

The communities identified by the RCFV (in recommendation 204) and through consultation are described in the framework as ‘priority communities’. They are: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) communities, people with disabilities, culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities, children and young people, and older people.

Administrative data

Administrative data refers to data typically collected by an agency or service provider as a by-product of providing services to clients or otherwise undertaking a core business activity

Mainstream services

Mainstream services in the context of this framework refers to any organisation which provides a service that is not primarily intended to identify or respond to family violence. Such services include police, education facilities, courts and healthcare services.

1 Royal Commission into Family Violence (RCFV) 2016, Volume 1 Report and recommendations, Victoria, p.9.

Introduction

During the RCFV, a number of common data gaps were identified in the current family violence evidence base.

Introduction

During the RCFV, a number of common data gaps were identified in the current family violence evidence base. It was noted that there is a lack of available data to support critical decision making, policy development, planning, research and evaluation activities. The report published by the RCFV outlined gaps in knowledge regarding:

- the demographic characteristics of priority communities, in particular, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) communities, people with disabilities, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities, and older people

- the number of unique clients and the extent to which individuals have multiple engagements with agencies and services related to family violence over time

- a person’s interactions with the system, which is based on the ability to link individuals across different data sets

- the extent of family violence beyond heterosexual intimate partner violence

Addressing the RCFV recommendations

The Crime Statistics Agency (CSA) was commissioned by the Department of Premier and Cabinet (DPC) to address a number of RCFV recommendations related to the collection and reporting of family violence data. The Victorian Family Violence Data Collection Framework (the framework) addresses aspects of three of these recommendations, with the relevant content of these summarised below.

This framework was been developed in consultation with a range of stakeholders, listed at page 109, and with significant input from Family Safety Victoria (FSV).

Recommendation 204 – Improve state-wide family violence data collection and research

Improvements to be made to state-wide family violence data collection and research, through developing a state-wide data framework, informed by relevant Commonwealth standards – for example, relevant Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) frameworks such as the National Data Collection and Reporting Framework (DCRF) guidelines and Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety (ANROWS) guidance. The framework should include guidelines on the collection of demographic information – in particular, on older people, people with disabilities and people from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, culturally and linguistically diverse and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex communities.

Recommendation 152 – Improve the collection of Indigenous data relating to family violence

Improve the collection of Indigenous-specific data relating to family violence so that this can be shared with communities, organisations and governance forums to inform local, regional and statewide responses.

Recommendation 170 – Adopt a consistent and comprehensive approach to data collection on people with disabilities

The Victorian Government will adopt a consistent and comprehensive approach to the collection of data on people with disabilities who experience or perpetrate family violence.

What is the framework?

The framework is a tool for government and non-government service providers and agencies who collect administrative data in the context of family violence. The framework will help service providers and agencies standardise the collection of administrative information, improving data collection practices and subsequently advancing the existing evidence base concerning family violence in Victoria.

The framework contains information and standards regarding the collection of general and demographic data items, with a particular focus on the community groups identified as a priority by the RCFV and through consultations conducted during the development of the framework. These groups include the priority groups listed in recommendation 204, as well as children and young people who were revealed as a key data gap during consultation.

The purpose of the framework is not to set a standard definition of family violence for government departments, agencies and service providers to use, as this is established through the Family Violence Protection Act 2008 (Vic). Instead, the framework is comprised of a set of data collection standards which organisations can elect to use in order to improve their collection of data concerning family violence. However, the framework is not intended to function as a data dictionary. As such, it is the responsibility of government departments, agencies and service providers to determine how each data collection standard can fit into their data collection guidelines and infrastructure.

The Victorian Family Violence Data Collection Framework focuses on driving improvement in data related to clients and their experiences of family violence. Improvements in the consistency and quality of this information will assist government, agencies and service providers to better understand:

- Who experiences family violence?

- Number of unique people affected (as victim survivors and perpetrators)

- Demographic profile of people involved

- Visibility of priority communities in data

- Barriers to access and need for assistance

- Geographic proximity to client base

- How do people experience family violence?

- Types of family violence experienced

- Persons involved and their role in the family violence

- Characteristics of an event

It should be noted that the framework does not include data items on types of service delivery, outputs or outcomes. Service delivery data items are determined by departments as part of their agreements with service providers. Outcomes specific to family violence are detailed in the Family Violence Outcomes Framework, published in Ending Family Violence: Victoria’s plan for change.

Who is the framework for?

The data collection standards presented in the framework are intended for use by all government departments, agencies or service providers who have the capacity to collect information in the context of family violence.

Figure 1 provides a broad overview of the services that have responsibility for responding to victim survivors or perpetrators of family violence and indicates the types of services the data collection framework is relevant to. This figure uses the four-tier classification originally developed by the Domestic Violence Resource Centre. The RCFV noted that these tiers provide a good starting point for thinking about workforce competencies, and they have been utilised within Building from Strength: 10-year industry plan for family violence prevention and response (Building from Strength) and the Responding to Family Violence Capability Framework.

Tier 1: Specialist family violence and sexual assault practitioners

These specialists spend 90% or more of their time working with victim survivors or perpetrators or engaged in primary prevention activities. Tier 1 practitioners or teams may form part of larger organisations that provide a range of services, or they may be employed in stand-alone services. What they have in common as practitioners is that their sole or major focus is on family violence and/or sexual assault, or on primary prevention.

- Statewide family violence crisis and specialist services

- The Orange Door

- Family violence outreach services

- Women’s refuges

- Centres Against Sexual Assault

- Perpetrator intervention services

- Men’s family violence telephone/online services

- Crisis family violence and sexual assault telephone/online services

- Specialist family violence or sexual assault professionals operating in Tier 2 or 3 services

- Specialist family violence or sexual assault services for Aboriginal or culturally and linguistically diverse women and children or women and children with a disability

Tier 2: Workers in core support services or intervention agencies

Responding to family violence is not the primary focus of these workforces, but they spend a significant proportion of their time responding to victim survivors or perpetrators.

- Courts and court services

- Legal and paralegal agencies and services

- Corrections

- Police

- Family dispute resolution services

- Forensic physicians and medical staff providing sexual assault crisis care

- Child Protection

- Child and Family Services

- Family and relationship services

- Homelessness services

Tier 3: Workers in mainstream services and non-family violence specific agencies

While their work is not family violence, they work in sectors that respond to the impacts of family violence, or in an area where early signs of people experiencing family violence can be noted.

- Health care services

- Drug and alcohol services

- Housing services

- Mental health services

- Centrelink

- Individuals providing therapeutic services

- Emergency services

- Maternal and Child Health Services

- Youth services

- Disability services

- Culturally and linguistically diverse services

- Aboriginal services

- Lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and gender diverse and intersex services

- Aged care services

Tier 4: Workers in universal services and organisations

Because they interact with children and families in their day-to-day roles, these workers are likely to have regular and extended contact with victim survivors or perpetrators.

Includes workplaces, education services, early childhood services, sport and recreation organisations and faith based institutions.

Figure 1: Workforces that have responsibility for responding to victim survivors or perpetrators. Modified from Building from Strength and the Responding to Family Violence Capability Framework.2, 3

In addition, although the data collection framework was created specifically to improve the quality of family violence data, it may also provide guidance for government departments, agencies and service providers striving to improve the quality and consistency of demographic information, both generally and from priority communities.

Why use the framework?

As previously noted, the RCFV found that there are serious gaps in our knowledge about the characteristics of victim survivors and perpetrators, and about how systems that respond to family violence are working. This is particularly with respect to people from priority communities.

In their report ‘Bridging the data gaps for family, domestic and sexual violence, 2013’, the ABS identified priority themes to improve the evidence base concerning family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia. The priorities identified were to:4

- improve the quality and comparability of existing data sources

- maximise the utility of existing sources

- augment existing data sources to address priority gap areas

The ABS noted the potential of administrative data sources to fulfil the aforementioned data needs. Administrative data are a useful source of information as they utilise existing infrastructure and have the potential to yield information about specific target populations. Data collected in this context are ideal for informing practical decisions about service provision, resource capacity and utilisation, as well as the impacts and outcomes of contact with services.

The content included in this framework aims to meet the priorities identified by the ABS concerning the collection of administrative data related to family violence in Victoria. Standardising the collection of demographic data items and improving administrative data on types of family violence can support broader work to build the evidence base about the impact of family violence on communities.

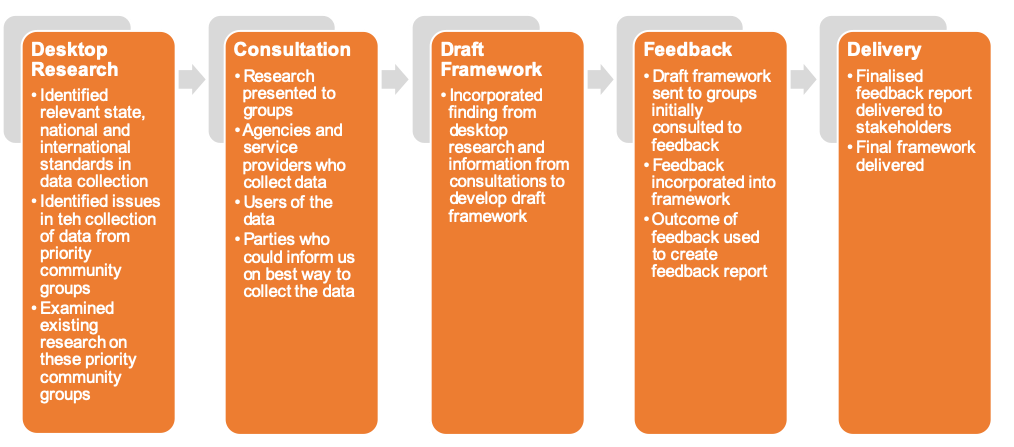

Development of the framework

Figure 2 below shoes the process carried out by the CSA to create the framework. Consultation was an essential part of the development of this framework. For a full list of stakeholders consulted, please see page 109.

2 Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) 2007, Family Violence Risk Assessment and Risk Management Framework, Victoria, p.9.

3 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2018, Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia 2018, Cat. no. FDV 2, Canberra.

4 Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2013, 4529.0.00.002 Bridging the data gaps for family, domestic and sexual violence, viewed 12 June 2018, www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/4529.0.00.002main+features332013

Data collection challenges and improvements

This section identifies common data collection challenges, as well as those more specific to collecting data on family violence, and from priority communities.

Organisations may face a number of challenges in collecting consistent and quality data. To develop methods to improve data collection practices, it is necessary to first identify barriers to consistent data collection. This section identifies common data collection challenges, as well as those more specific to collecting data on family violence, and from priority communities. The section also provides advice about how to address some of these challenges and improve data collection. Government departments, agencies and service providers with responsibility for data collections should consider these challenges and improvement opportunities as part of implementation planning. Additional data collection challenges that are specific to particular communities are discussed in the priority community sections of this paper.

Challenges in current data collection practices

Inconsistent data collection standards

Data standards outline how common data items and demographic information should be collected. Established standards typically contain data definitions, standardised questions and accepted response options which guide consistent collection practices. Currently, there are many national and state-wide data standards which are used for collecting administrative data. These standards are not always broadly applied, and may themselves be inconsistent, and this can impact the comparability of data collections.

For example, many specialist and non-disability specific support services collect data on disability drawing on definitions used by the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), the National Disability Agreement and state governing bodies. Different types of services may apply different standards depending on what is most relevant for their service provision. For example, medical services may be more likely to collect disability information by way of diagnoses and medical history, while non-disability specific services may be more interested in collecting information concerning support needs or a need for reasonable adjustments. As a result, the scope and detail of information collection may not be consistent across services, making it complex to compare data between services, or to population level data sets.

The absence to date of a co-ordinated effort between government, service providers and other agencies to standardise data collection practices means there is considerable variation in how information is collected and recorded in Victoria in relation to family violence and to priority communities.

Context of data collection

Data collection from clients may occur in a variety of situations and settings where it can be difficult to obtain complete and accurate information, and the amount of information gathered may vary depending on the context of the situation. In most cases, the person responsible for collecting data has a primary role that focusses on the provision of a service (for example, as a police officer, support worker or medical practitioner) and, although they collect data as part of these roles, data collection is not necessarily the primary function of their role. Contexts where certain data collection may be limited include crisis or emergency situations, where workers are prioritising the safety of an individual, or situations where an individual’s privacy may be compromised by asking about family violence, such as in a busy waiting room.

Further, in some cases, organisations may not be resourced to provide services to specific cohorts, which can mean there is little incentive to improve the data collected on these individuals in an administrative setting. For example, some family violence services are not specifically resourced to meet children’s needs and may therefore not collect detailed information on this cohort. Conversely, improved data collection on priority communities can help build an evidence base from which to consider different funding models.

Data collection is not core to business function

The core functions of an organisation and time pressures in service delivery can impact the type and quality of data that an organisation collects. Administrative data are typically collected as a by-product of operational requirements or to meet an internal business need and may only include core information needed to perform a service, such as a client’s contact details. In such cases, information on an individual’s sexual orientation, cultural background or disability may not be seen as an operational requirement for organisations that do not offer specialised services. As a result, organisations may only collect a narrow range of data items, which lack sufficient detail needed for broader secondary use purposes, such as conducting state-wide service analysis, monitoring or research.

A perception that the collection of certain demographic information is not relevant to core business functions can impact data quality and comparability for all priority communities discussed in this framework. For example, while many services are legally obliged to collect information on a person’s requirement for an interpreter, other information on their cultural background may not be deemed as relevant to service delivery, resulting in partial information on CALD communities. Concerns have also been raised about how the collection of Aboriginal information may contravene an organisation’s commitment to equitable service delivery5, despite the fact that a person’s response to this question should not impact the standard of service they receive.

Complexity

In some cases, adequate information about a person’s background cannot be ascertained through one data item, for example for CALD and LGBTI communities, and for people with disabilities. Where this is attempted, it often under-represents those who face heightened risks and barriers to accessing services. It also has the potential to add confusion regarding different concepts that may not be fully understood by people outside of specific communities. For example, grouping diverse people and communities into a single ‘LGBTI’ group, or using the need for an interpreter as a marker of CALD communities, does not recognise and represent these communities accurately, and decreases data integrity.

Lack of training in data collection

As the primary role of front-line service and clinical staff will generally not be data collection, they may not receive training in this area. If staff do not receive training or understand why they need to collect particular data, they may feel less confident to ask the associated questions, or ask them in a different way. A lack of training in how and why to collect certain kinds of data can particularly impact the priority communities discussed in this framework. For example, given the personal nature surrounding questions about sexual orientation or intersex variation, organisations may be reluctant to ask for this information, particularly if there are concerns that this may cause a person to be offended or experience discomfort. A fear of causing offence may also impact staff willingness to ask questions about a person’s disability, cultural background or Indigenous status, and lead them to make assumptions based on observation or on information being volunteered. Staff training in the benefit of collecting these data items, and in sensitive or culturally appropriate ways to do so, can build staff understanding of the value of these types of data, and assist in building data quality and consistency.

Lack of quality assurance processes

There may be limited opportunities to confirm information with a person who has been in contact with a service, meaning that the data initially collected cannot be verified. Additionally, the sophistication of record keeping systems can vary and data quality is often reliant on the person entering the data correctly. Depending on the resourcing of an organisation, time may not permit staff to review information for completeness and obtain missing data.

Changes to definitions and policies and maintaining data comparability

Over time, best practice data collection policies and procedures change. Agencies and their staff may not be aware of these changes and how they affect them, meaning that they inadvertently follow outdated practices. This issue tends to be more prevalent in large organisations, particularly if information is not communicated widely and consistently throughout the workplace. Also, if training is not provided to reinforce changes in practice, staff may continue to follow the procedures they are most familiar with.

Organisations changing data collection systems and processes also need to be aware of the need to ensure continuity of reporting using existing data items. For example, many service providers are bound by the requirements of their funding body to provide particular data fields on a regular basis. Furthermore, in some cases these minimum requirements are established at the federal level, rather than by Victorian state government departments. Longitudinal analysis of service usage based on common data items, and comparability to national data sets, such as those of the ABS, are another consideration when updating data collections.

Economic and IT restrictions

Some organisations may not have the capacity or infrastructure to prioritise improvements to data collection systems and processes. This may be due to a backlog of paper-based records to be digitised, a small workforce to input and maintain data, and lack of budget to upgrade records management systems. It is also important to note that many IT systems are provided by government departments, who also carry the responsibility of resourcing and conducting system updates. These updates can be expensive and take time. In some cases, these IT systems may have limited capacity to include multiple response values or dynamic questioning, that supports sophisticated data collection. The introduction of multiple response options may also present problems for exporting and analysing data.

Improving data collection

The remainder of this section provides information on improving data collection practices in general. It includes a range of processes that can be implemented at the organisational level, and through changes in infrastructure and data collection practices. It also provides advice on interim process for improving data quality for analysis and reporting purposes, and information on privacy and security requirements.

Organisational Practices

Commitment from all levels of an organisation to improve data collection

Improving data collection and the quality of data holdings requires a concerted effort from an entire organisation, and should begin with a top-down commitment for change. This includes identifying priority areas for improvement and barriers to improvement, adopting best practice procedures for collecting quality data, using data standards where available (including those recommended in this framework), ensuring IT infrastructure is kept up to date and allows for efficient and effective data collection, and providing training where needed to those collecting data to ensure confidence and consistency in data collection practices.

Training

It is important to provide training to staff involved in the collection of data. Training should emphasise why it is important to collect data and highlight the benefits of data for operations, planning, research and evaluation. If staff understand the rationale for collecting certain information, they will feel more confident to ask for these data items and to explain why it is important. Training should include how to phrase questions, clarify answers and record responses.

Using data-related Key Performance Indicators (KPIs)

Setting KPIs linked to data and evidence can be a motivating factor for organisations to ensure improvement in their data collection practices. KPIs can target many aspects of data quality including completeness (how many records have a recorded value), and precision (how many records have a meaningful or valid value). Organisations should set reasonable KPIs that aim to improve the quality of their data, but not create perverse incentives that could undermine data quality or service delivery.

For example, an organisation finds that only 50% of the clients contained within their record management system have a recorded gender. The organisation sets a KPI for 100% of clients to have a recorded gender, and they monitor this goal over the course of a six-month period to ensure that improvements made are effectively moving towards this goal.

Conducting audits and business process reviews

If possible, it is recommended that audits of datasets are conducted at regular intervals to ensure accuracy and completeness of recorded data. Audits may illuminate systemic or recurring issues in data collection that can be addressed once identified. Similarly, reviews of business processes can identify difficulties in data collection and assist an organisation to understand the barriers to quality data collection. Conducting audits and business review processes can also be a component of evaluating the success of KPIs.

Infrastructure and Collection Practices

Data items have pre-defined responses

Where appropriate, it is recommended that data items have a pre-defined set of response options at the point of entry into a data management system. This reduces the potential for typographical errors and enables more efficient data collection and subsequent analysis. However, there may be instances where a free text field should be provided. Recommended response options and instances where free text coding should be allowed will be discussed in the data collection standards proposed in this framework.

Accommodation of multiple response options

There are some priority data items where it is not ideal to collect only one response from a person. For example, when asking a person to describe their disability, a person may disclose that they are blind and have mobility difficulties. In this case, it may be restrictive to ask someone to choose between response options when recording their disability type. It is acknowledged that allowing for multiple response options can create complexities both for IT infrastructure and for analysis of the collected data, however it is recommended that for certain data items, agencies and services consider approaches which accommodate multiple response options.

Creating mandatory data fields

Where appropriate, it is advised that service providers and agencies update their data collection infrastructure to utilise mandatory data fields (or at minimum, prompts, on all non-optional data items). Therefore, the person inputting the data cannot move to the next screen without entering a response in mandatory data fields. Incorporating mandatory data fields into a records management system ensures that all non-optional data items receive a response. However, it is important to remember that people have the right to not respond to a question.

For example, to improve their collection of gender information, an organisation updates their data entry system so that a response for gender must be recorded when entering details about a new client before the new entry can be completed. The organisation now finds that 100% of all new client records have a recorded response for gender.

Guidance for collecting data in written form and verbally

Regardless of whether data collection is written (form-based) or verbal, using the question phrasing and response options outlined in each data item is recommended. Further, it is generally recommended that data are collected directly from a client, rather than by proxy, particularly for sensitive information such as a person’s sexual identity or orientation.

| Collecting data via a third party |

|---|

| Although it is preferable for data to be gathered directly from a person, this may not always be possible. Agencies and services should have their own policies which dictate where it is acceptable for communication (and by proxy, data collection) to take place through an agreed upon third party. Agencies and services should be aware that in some cases a person’s guardian or representative may be the perpetrator of family violence against that person. If such a circumstance is suspected, agencies and services are encouraged to have protocol in place to help assist victims so that the offending party is not speaking on behalf of the victim. |

Where data are collected from a respondent verbally, questions should be asked as they are written, and data collectors should describe the response options available for each question. Detailing the full list of response options across data items can have a range of benefits, including communicating that an organisation is inclusive of a broad range of identities, as well as assisting respondents with choosing the most appropriate category for them. In some cases, such as for the disability data items, respondents may need additional information to understand the scope of categories, and data collector should provide information and guidance to assist with understanding each of the categories.

Where possible, all available categories in a data item or classification being used should be read or provided to a respondent rather than a short-list. However in cases where the context of the data collection does not allow for this, the question can be asked on its own. Managing long lists of response options is particularly relevant to questions about country of birth and language spoken at home, where there is an extensive range of options a person may choose. If a short-list is being used, and a respondent’s answer is a category in the short-list, this category should be selected. Where their answer is not in the short-list of response categories, the data collector can select ‘other’ and where possible, enter the response in the text field.

Because communities may have unique, or an extensive range of terms to describe identities, such as sexual identity or ethnicity, it may be necessary to clarify the term used with the respondent. For example, if a client responds to a question on gender identity as ‘non-binary’, the data collector should confirm with the client that this aligns with the ‘self-described’ response category, and write ‘nonbinary’ in the free text field which accompanies that option. Responses should not be questioned or assumed based on a person’s appearance or other information that has already been disclosed.

Including response options for ‘prefer not to say’, ‘question unable to be asked’ and ‘no response’

Inevitably, there are circumstances where it is not possible to obtain certain information. It is recommended to include response options for priority items that will help provide details about why information was not able to be collected. This can be used to evaluate collection practices, and determine if solutions can be implemented to better address gaps in data. There are some data items that may involve the disclosure of sensitive information. Hence, it is recommended to provide respondents with a ‘prefer not to say’ option, which respects a person’s choice not to disclose particular information. Including this as an option also enables data analysis to determine where the question was asked and the response is not missing or unknown for other reasons.

When questions are asked of people verbally, it is possible that the data collector will be unable to gain all the required information. This may be due to the context in which the information is being gathered (for example, an emergency event), or to other unexpected events (for example, a client abruptly hangs up the phone). In these cases, it is ideal to include the response option ‘question unable to be asked’, which explains why the information was unable to be recorded.

When questions are asked of people by form or online, a person may choose to not complete all questions. In these cases, it is recommended to include a response option for ‘no response’, for when this information is subsequently lodged in a data records system.

For example, an organisation is pleased to find that they have achieved their goal of 100% of all clients having a recorded gender. Upon closer analysis of the records however, the organisation finds that 40% of the records have a gender recorded as ‘unknown’. As all data are collected verbally from clients, they update their records management system to allow for response options for ‘prefer not to say’ and ‘question unable to be asked’. Over time, they find that for 30% of all clients, a question about their gender is unable to be asked.

Following up to obtain additional data

It is acknowledged that certain situations do not permit the collection of comprehensive data. Where feasible, it is recommended that missing data are followed up at an appropriate time. In particular, organisations that work with people in a crisis or emergency situation should obtain data required to deliver the immediate service, and then follow up for further information once the crisis or emergency has been managed. The follow up to address data gaps could accompany an existing operational task, including a routine call to ensure the welfare of a patient or client following a service.

For example, an organisation finds that 30% of their client records have a response value of ‘question unable to be asked’ for gender. After consulting with front-line staff, it emerges that information is typically gained from clients while they are accessing an emergency service. The organisation may decide it is appropriate to implement a follow up later which includes collecting missing data items.

Interim improvements for analysis and reporting purposes

Improving the quality of demographic data within one data source

In cases where clients are presenting over multiple occasions and there is partial coverage of a data item, there are post-hoc data improvement processes that can be implemented to superficially improve the quality of the data. It is important to note that historical responses to data items should remain unchanged, and the application of any of the methods below should update only the most current status. There are three options to improving the quality of demographic data, all of which have advantages and disadvantages. These rules that summarised below are drawn from the CSA’s ‘Consultation paper: Improving recorded crime statistics for Victoria’s Aboriginal community’6. However, the approach is more broadly relevant to other demographic identifiers:

- Application of an ‘ever-identified’ rule - Using this method, a person who has identified at one point in time as being of Aboriginal would then be given this status across all of their other records in the database.

- Application of a ‘most recent identification’ rule - Using this method, a person’s most recent Indigenous status would be applied across all of their other records in the database.

- Application of a ‘most frequent’ rule - Under this method, a person’s most frequent response to the SIQ would be applied across all of their other records in the database.

For the purposes of analysis and reporting on Victoria Police crime data, the CSA applied the ‘most frequent’ rule to Indigenous status to improve the quality of the Indigenous status variable in victim and offender analyses. Overall, feedback received by the CSA indicated that this rule was the favoured methodology.7 This concept can be applied across other datasets where individual clients can be identified across a database and would provide an interim measure while other data improvement processes are developed and implemented.

Improving the quality of data across multiple data sources

In addition to using one of the methods outlined above, it is also possible to use multiple data sources to identify a person’s certain demographic or community data items even where it is not directly collected as a result of a service or business process. This involves linking a person across the datasets using key pieces of information and attributing that data category in one data source to their profile in another source.

Privacy and security considerations

This section outlines some of the privacy principles that public sector organisations should be aware of when collecting and storing data. If policies and procedures regarding the secure storage and transfer of data are not already in place, organisations may be reluctant to collect personal information if it is not imperative for their operations. However, this section is not intended to provide extensive privacy and security guidance; instead organisations should refer to any relevant legislative, regulatory and administrative provisions for further information.

Information Privacy Principles (IPPs) and Health Privacy Principles (HPPs) are privacy principles which govern the way that public sector organisations, including contracted service providers, collect, use and handle personal and health information. The IPPs apply to personal information under the Privacy and Data Protection Act 2014 (Vic) (PDPA), while the HPPs apply to health information under the Health Records Act 2001 (Vic) (HRA).8 Privacy principles that are particularly relevant to the framework include; IPP/HPP 1 (Collection), IPP/HPP 3 (Data quality), IPP/HPP 4 (Data security), IPP/HPP 8 (Anonymity), and IPP 10 (Sensitive information).

The Office of the Victorian Information Commissioner has developed the Victorian Protective Data Security Framework (VPDSF), which provides comprehensive information on managing data security risks from the point of data collection and throughout the information lifecycle.9 The standards in the VPDSF relate to data governance, information security, personnel security, Information Communications Technology security, and physical security. It is recommended that organisations review and adopt these protocols prior to data collection.

In addition to the IPPs and HPPs, there are a number of other policies and laws that make up the Victorian information management landscape, which agencies should consider when developing their own privacy and security policies. In particular, organisations should turn to their enabling legislation as a starting point in determining the information they are permitted to collect.

In particular government departments, agencies and service providers should be aware of their obligations where prescribed under the Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme (FVIS Scheme) and the Child Information Sharing Scheme (CIS Scheme)10. The FVIS Scheme and CIS Scheme are aimed at removing barriers to information sharing to allow professionals to work together across the service system, to make more informed decisions and better respond to the safety and wellbeing needs of individuals, children and families. The requirements of Schemes, including record keeping requirements, are detailed in the Family Violence Information Sharing Guidelines and the Child Information Sharing Guidelines. When services are sharing information under these schemes, the Victorian Protective Data Security Standards will continue to apply.

Organisations are encouraged to seek advice prior to implementating the data items proposed in this framework to ensure compliance with relevant privacy legislation. Individual organisations are responsible for ensuring that their business practices are compliant with State and Commonwealth privacy requirements and information sharing schemes, and should seek guidance from privacy advisors, legal teams, the Office of the Victorian Information Commissioner and/or the Health Complaints Commissioner when unsure about their obligations.

5 AIHW 2010, National best practice guidelines for collecting Indigenous status in health data sets, Cat. no. IHW 29, Canberra, p.3.

6 CSA 2016, Consultation paper: Improving recorded crime statistics for Victoria’s Aboriginal community, viewed 22 June 2018,

www.crimestatistics.vic.gov.au/about-the-data/consultation-paper-improving-recorded-crime-statistics-for-victorias-aboriginal(opens in a new window)

7 CSA 2016, Outcomes of recent public consultation: proposed methods to improve Victorian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

recorded crime statistics, viewed 22 June 2018, https://www.crimestatistics.vic.gov.au/media-centre/news/outcomes-of-recent-public-consultation-proposed-methods-to-improve-victorian(opens in a new window)

8 Commissioner for Privacy and Data Protection 2016, Information sheet: Information Privacy Principles and Health Privacy Principles – May 2016, viewed 12 June 2018, www.cpdp.vic.gov.au/menu-resources/resources-privacy/resources-privacy-…

9 Office of the Victorian Information Commissioner 2018, Victorian Protective Data Security Framework – March 2018, viewed 20 June 2018, www.cpdp.vic.gov.au/menu-data-security/victorian-protective-data-security-framework/vpdsf(opens in a new window)

10 Department of Education and Training, The Child Information Sharing (CIS) Scheme and The Family Violence Information Sharing (FVIS) Scheme available at https://engage.vic.gov.au/child-information-sharing-scheme(opens in a new window)

Data collection standards - General data items

This section discusses the importance of collecting general data items.

This section discusses the importance of collecting general data items, and presents existing national standards which should be used to ensure consistent and high quality collection of data by Victorian government departments, agencies and service providers.

Individual and demographic data items

Collecting information from people who come into contact with agencies and service providers is often a balancing act between respecting the privacy of individuals, gaining enough information to perform core business functions, making informed decisions about service use, and providing a deeper understanding about the experiences of people affected by family violence. Individual and demographic information is particularly valuable for creating a demographic profile of those affected by family violence, and is therefore essential in improving the family violence evidence base in Victoria. This section highlights data items which can be used to improve the quality and consistency of individual and demographic information on people who come into contact with an agency or service.

Names

Details about a person’s name are commonly collected by agencies and service providers. This information can be used by organisations as the primary identifier of a person’s identity, and is often necessary when seeking to count unique individuals who come into contact with an agency or service. Names are also an important component for data linkage projects, which are increasingly becoming a priority across government departments in Australia, enabling improved understanding of client pathways across agencies and services. It is therefore important that name information is collected consistently and accurately. The Commonwealth Attorney-General’s Department recognised the need to capture accurate and detailed information on people’s names, and published better practice guidelines for the collection of identity data in 2011.11 While these guidelines are targeted at Commonwealth agencies, the document sets out several principles that are valuable for all agencies and services that collect name information for the purpose of establishing identity. Some of the key principles in these guidelines are outlined below.

Information should be collected whenever possible. While there are some contexts where collection of a person’s name may not be appropriate, including where services are provided anonymously, information should be collected about a person’s first and last name whenever a person consents to provide it.

Information should reflect what is written on an official ID document. In order to ensure that information collected on names is done so uniformly and accurately, given names and family names should be recorded as they are written on an official government identification document. Data collectors should avoid recording nicknames, initials or abbreviated names in the given and last name fields, and instead, these should be captured in separate data fields. Whenever possible, nonalphabetical features should be collected as they appear in a name on official identification (including hyphens and spaces), as this is a feature which can improve the uniqueness of collected names.

It is noted that asking people to produce an ID document to verify their name may present a number of operational challenges or may not be possible given the nature of some services (for example, telephone-based services). A requirement to provide an official ID document may be challenging or offend people from some priority communities. For the reasons discussed, it is important to collect name information as recorded on official ID documents. However, unless official identification is required to be sighted by a service, it is recommended that people are not asked to provide an ID document to verify their name.

Additional name information should be collected. People frequently use names other than the name recorded on their identification document. If a person has a nickname or different name they use, this information should be collected in addition to the name appearing on their identification document. Staff should use this name during all communications with that person.

Please note that when asking if someone uses a different name than what is recorded on their identification document, it may be considered offensive to ask what their ‘preferred’ name is. This is particularly true for some trans and gender diverse people, and as such it is not recommended that agencies use the word ‘preferred’ when asking about the name that a person uses. For more information, please see the LGBTI communities section of this framework, which provides specific advice regarding the collection of information from LGBTI people.

Examples of name questions:

What is your given name[s], as it is recorded on government issued ID?

What name do you use? [if different from given name/s]

What is your family name, as it is recorded on government issued ID?

Name usage type. To assist with differentiating between the types of names collected, agencies or service providers may elect to use a data item which indicates the type of name used. Name usage type (METeOR identifier: 453366) concerns the usage type of a person’s family name and/or given name and enables differentiation between each recorded name.12

Records should be updated where appropriate and historical records retained. It is acknowledged that people often change the name that is recorded on their official ID document for a variety of reasons. Name information should be kept up-to-date to reflect the current information recorded on a person’s identification documents. Wherever possible, historical records of a person’s name should be retained, as this provides greater potential to confirm a person’s identity.13

Age / Date of birth

Age is a widely collected data item across agencies and service providers, however the method by which it is collected varies. Some offices collect age as a discreet number (for example, ‘65’), a predefined group (for example, ‘60 and older’) or as a date of birth which is later used to derive a person’s age.

The standard recommended in this framework is to collect age in the form of an individual’s date of birth. Date of birth should be collected in accordance with the format described by METeOR identifier 287007, which is DDMMYYYY. Collecting date of birth has the advantage of providing more detailed and accurate information about a person’s age, and it can be used for other purposes, including identifying unique individuals and linking datasets. The ABS has noted that “collecting age in complete years can lead to an error where a respondent may round off or approximate their age”.14 Additionally, collecting age as a number fixes a client age to the year in which it was collected, and the information loses meaning if it is unclear when the age was recorded. This is particularly true when a client interacts with an organisation over a long period of time.

Wherever possible, an agency should ask for the date of birth that an individual uses on their official ID documents. As with name information, unless official identification is required to be sighted by a service, it is recommended that people are not asked to provide an ID document to verify their date of birth.

It is noted that there are instances where an individual may not know their birth date, or where they are only able to supply a numerical estimate of their age. The date of birth standard used in a number of national minimum datasets (METeOR identifier: 287007) suggests that if date of birth is not known or cannot be obtained, provision should be made to collect or estimate age. Collected or estimated age would usually be in years for people 2 years and older, and to the nearest 3 months (or less) for children aged less than 2 years old. An estimated date of birth may also be relevant for unborn children. A child believed to be aged 18 months in January 2018 would therefore have an estimated birthdate of 01062016.15

When a recorded date of birth has been estimated, it is recommended that an indicator is used to denote that the date is an estimate. Information regarding best practice for indicating estimated dates is discussed later in this section.

Example of age question:

What is your date of birth [as it is recorded on your birth certificate or other form of identification]? DDMMYYYY

Date variables

Most organisations who collect data will record some type of date information. This can include the date when a service was initiated, attended and completed, when family violence was disclosed, when a family violence incident occurred, or, as previously noted, date of birth. To ensure that high quality date information is collected, it is recommended that dates are completed in full whenever possible, and contain an accurate record of the day, month and year.

In Australia, the date format most commonly used is DDMMYYYY. It is recommended that information is collected and stored in this format.

Finally, it is recommended that organisations collect a ‘create date’ or similar data item. This date represents the date an electronic record is created to be stored in an administrative data collection system. It is strongly recommended that the create date is auto-generated at the time that a case or record is first created. If records are promptly entered into a records management system, this approach ensures that the date is consistently and accurately collected.

Estimated dates. When a date is estimated, agencies and service providers are encouraged to use a data item which indicates that the date is an estimate. When estimating dates, Date – accuracy indicator (METeOR identifier: 294429) can be utilised to indicate which parts of the recorded date are known, estimated and unknown. The table below depicts how three codes are used in combination to provide information about the accuracy of a recorded date. For a full list of response options, please see the METeOR website.16

| Data domain | Day | Month | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accurate | A | A | A |

| Estimated | E | E | E |

| Unknown | U | U | U |

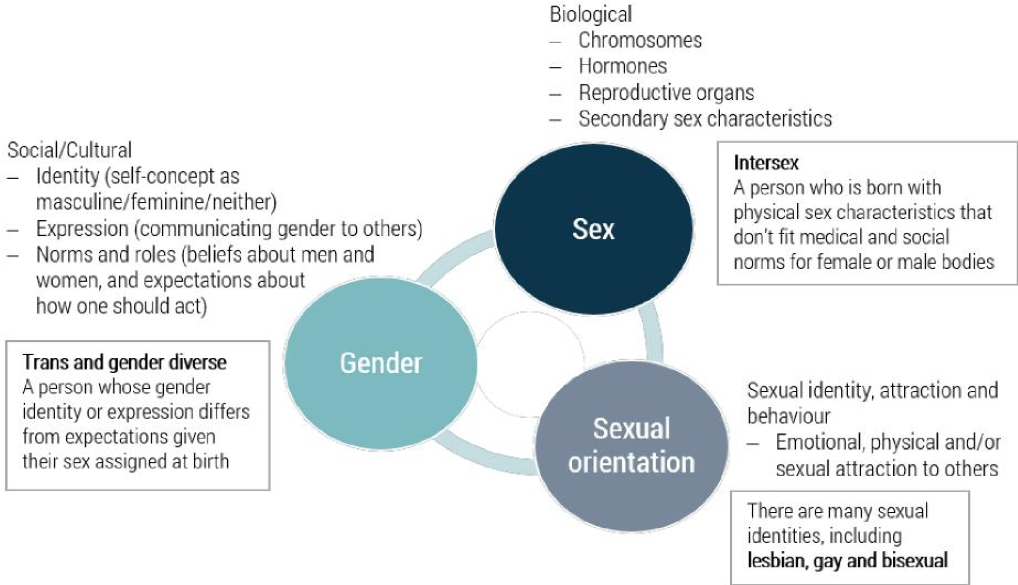

Gender identity and sex

Most agencies and service providers will collect information on a person’s sex or gender identity. Due to the overlap between these data items and information concerning LGBTI communities, the standard suggested for collecting this information is described in detail in the LGBTI communities section of this framework.

Geographic variables

Agencies and service providers may collect a range of geographic information surrounding family violence, depending on their operational purpose and the services that they provide. Examples of geographic data collected include the home address of a victim-survivor or perpetrator (person address) and the address of where a service is provided (organisation address).

Many agencies and service providers will collect geographic information as aggregated regions, for example, Local Government Areas (LGAs) or Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) service regions. While this information may satisfy internal demands, it can have limited value for research purposes or when looking to compare data with population-based statistics. Additionally, geographic areas such as LGAs and other administrative service regions change over time.

Collecting detailed geographic information allows data to be mapped to higher level geographic structures as needed, such as those that exist in the ABS Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS) 2016.17 The ‘Address Details Data Dictionary’ (METeOR identifier: 434713) created by the AIHW sets out address information which is important to collect for these purposes. As recommended by the data dictionary, when collecting information on addresses agencies and service providers should collect primary address information. This includes:18

- address site (or primary complex) name

- address number or number range

- road name (name/type/suffix)

- locality

- state/territory

- postcode

- country (if other than Australia)

In 2010, DHHS released their ‘Address reference data dictionary (version 1.1)’,19 which provides a common set of concepts, data elements and edit/validation rules that define the basis of address data collection. If interested in collecting data elements outside of the primary address information listed above, this data dictionary draws on existing national standards to assist data collection custodians to better document and manage address data. It is therefore a valuable resource for agencies and service providers to consider when seeking to align their address data items with national standards.

Unique identifiers and data linkage considerations

Unique identifiers

Unique identifiers (UIDs) can be used in a variety of contexts, but typically their purpose is to identify a unique item, person or case file. Often UIDs will consist of a distinct combination of letters and numbers that are randomly assigned and auto-generated by a records management system, however they may also be borrowed from other forms of identification codes. For example, some services may use a person’s driver’s license or passport number as their UID, or they may adopt a UID given by a different system (for example, courts may use the person identification number created by Victoria Police’s Law Enforcement Assistance Program (LEAP) system).

Examples of unique identifiers:

Case file number: C14-12-002 Client number: Z103903

Where UIDs are used, it is recommended that agencies and service providers ensure that the numbers given to clients are always unique, and that there is a protocol in place to prevent UIDs or clients from being duplicated.

The Office of the Victorian Information Commissioner has created an Information Sheet concerning the use of UIDs and relevant considerations under the Privacy and Data Protection Act 2014 (Vic).20 Organisations should review their obligations under relevant legislation in Victoria when considering implementing the use of UIDs for identifying individuals.

Statistical Linkage Key (SLK): As described by the AIHW in METeOR identifier 686241, an SLK is a key that enables two or more records belonging to the same individual to be brought together. It is a 14 character string represented by a code consisting of the second, third and fifth alphanumeric characters of a person’s family name, the second and third alphanumeric characters of a person’s given name, the day, month and year when the person was born (in the format DDMMYYYY) and a single alphanumeric character representing the sex of a person, concatenated in that order:21

XXXXXDDMMYYYYX

SLKs are valuable for collection because they not only serve as unique identifiers which assist with counting unique people accessing a service, but as they are uniformly created, they can be used to link individuals across internal and external data sets.

Data linkage

The potential to link datasets between agencies and service providers is becoming a matter of priority in Australia. Recommendation 204 of the RCFV specifically mentions the need to explore “opportunities for data linkage between existing data sets...to increase the relevance and accessibility of existing data”.22 Data linkage can also provide greater insight into perpetrator and victim-survivor engagement with services, and an opportunity to view an individual’s trajectory through the criminal justice and community services systems.

The most significant data items which assist with data linkage are those that can be used to denote unique individuals, cases, times and locations. Often the most desirable information which can be used for this purpose are high quality UIDs. Specific details concerning UIDs are described earlier in this section, however it is worth noting that for linkage purposes, the collection of external UIDs in combination with internally created UIDs is ideal. For example, a service may receive an L17 Risk Assessment and Management form from Victoria Police as part of an application or a referral for service, and where possible, agencies should collect the incident number that is recorded on this form, in addition to creating their own file ID and client ID. Retaining the incident number assigned by Victoria Police will allow for data collected by a service to be easily and reliably linked back to Victoria Police data if required.

Other data items can be used for linkage purposes if they are collected in a consistent and accurate manner. These items include first and last name, date of birth and sex or gender information. Best practice methods for collecting this information are described earlier in this section.

11 Department of Home Affairs 2011, Improving the Integrity of Identity Data: Recording of a Name to Establish Identity 2011,

Attorney-General’s Department, viewed 12 June 2018, www.homeaffairs.gov.au/about/crime/identity-security/guidelines-andstandards

12 AIHW Metadata Online Registry, Person – name usage type, code AAA, viewed 20 June 2018,

http://meteor.aihw.gov.au/content/index.phtml/itemId/453366

13 Department of Home Affairs 2011, Improving the Integrity of Identity Data: Recording of a Name to Establish Identity 2011,

Attorney-General’s Department, viewed 12 June 2018, www.homeaffairs.gov.au/about/crime/identity-security/guidelines-andstandards

14 ABS 2014, 1200.0.55.006 Age Standard Version 1.7, viewed 20 June 2018, www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/1200.0.55.006main+features72014,%20Version%201.7

15 AIHW Metadata Online Registry, Person – date of birth, DDMMYYYY, viewed 12 June 2018,

http://meteor.aihw.gov.au/content/index.phtml/itemld/287007

16 AIHW Metadata Online Registry, Date – accuracy indicator, code AAA, viewed 12 June 2018,

http://meteor.aihw.gov.au/content/index.phtml/itemld/294429

17 ABS 2016, 1270.0.55.001 Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS): Volume 1 – Main Structure and Greater Capital City Statistical Areas, viewed 20 June 2018, www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/1270.0.55.001

18 AIHW Metadata Online Registry, Address details data dictionary, viewed 20 June 2018,

http://meteor.aihw.gov.au/content/index.phtml/itemId/434713

19 DHHS 2010, Address reference data dictionary version 1.1, viewed 20 June 2018, www2.health.vic.gov.au/about/publications/policiesandguidelines/data-dictionary-address-reference

20 Commissioner for Privacy and Data Protection 2017, Information sheet: ‘Unique Identifier’ under the Privacy and Data Protection Act 2014 (Vic), viewed 12 June 2018, www.cpdp.vic.gov.au/menu-resources/resources-privacy/resources-privacy-information-sheets

21 AIHW Metadata Online Registry, Record – linkage key, code 581 XXXXXDDMMYYYYX, viewed 13 June 2018,

http://meteor.aihw.gov.au/content/index.phtml/itemld/686241

22 RCFV 2016, Summary and recommendations, Victoria, p.101.

Data collection standards - Family violence data items

Introduces a set of family violence data items that are intended to support consistent recording of core information concerning family violence.

The RCFV identified a range of gaps in family violence data and in systems for comprehensively recording and assessing data. Some of these gaps stem from under-recording and hidden reporting of family violence, and others from limited demographic information and inconsistent definitions in collecting data. This section introduces a set of family violence data items that are intended to support consistent recording of core information concerning family violence. This includes the type of family violence, the relationships between the person using family violence and those affected by it (namely, nature of the familial relationship), and whether the person accessing the service at a particular point in time is identified as the victim or perpetrator of family violence.

The questions and responses included in this section are not intended to function as a check-list to determine whether or not an incident constitutes family violence. Nor are they intended to assist staff in identifying if a client is at risk of family violence. Their purpose is to operate as a defined set of data items that will support greater consistency in recording information about family violence in administrative data.

A range of work is underway as part of the Victorian Government family violence reforms to support organisations and practitioners to better understand, identify and respond to family violence. This includes workforce training and development activities detailed within Building from Strength and within the Responding to Family Violence Capability Framework. The Family Violence Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management Framework (MARAM) provides tools and guidance for organisations and professionals on how to identify and assess family violence and risk; and how to respond within their legal obligations. MARAM provides evidence-based family violence risk factors, and questions to support identification and assessment of family violence risk, and is a useful references for departments, agencies and service providers on best practice standards for identifying and responding to family violence risk.

| Family Violence Risk Assessment and Risk Management Framework |

|---|

|

The Family Violence Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management Framework has been established in law under a new Part 11 of the Family Violence Protection Act 2008 (Vic). This requires organisations that are prescribed through regulations, as well as organisations providing funded services relevant to family violence risk assessment and management, to align their policies, procedures, practice guidance and tools to the MARAM Framework. The MARAM Framework provides policy guidance to organisations prescribed under regulations that have responsibilities in assessing and managing family violence risk. It provides support to organisations and professionals to recognise a wider range of presentations of risk for children, older people and diverse communities, across identities, family and relationship types and will keep perpetrators in view and hold them accountable for their actions and behaviours. Under MARAM:

|

Terminology and definitions

Defining family violence

Family violence is behaviour that controls or dominates a family member and causes them to fear for their own or another person’s safety or wellbeing and includes exposing a child to these behaviours. Family violence presents across a spectrum of risk severity, from subtle exploitation of power imbalances, through to escalating patterns of abuse over time.

The Victorian Family Violence Protection Act 2008 (Vic) (FVPA) uses broad definitions of family violence and ‘family’ or ‘family-like’ relationships.

| Definition of family violence |

|---|

|

The FVPA identifies family violence as – (1)(a) behaviour by a person towards a family member of that person if that behaviour – (i) is physically or sexually abusive (b) behaviour by a person that causes a child to hear or witness, or otherwise be exposed to the effects of behaviour referred to in paragraph (a).23 Examples of family violence that are referred to in the FVPA include:

|

Family violence is much broader than the physical component that is commonly associated with the term. It is vital that organisations working with clients affected by family violence understand all the types of violence experienced by their clients. This is particularly important for abuse which is harder to recognise, including controlling behaviours, isolation, sexual assault, financial, emotional and spiritual abuse. Acts of family violence may constitute a range of criminal or civil offences. The MARAM Framework outlines all family violence risk factors, which individually or in combination are used to identify the presence of family violence risk. MARAM risk factors are the basis upon which family violence risk is assessed in Victoria. The MARAM risk factors can be categorised into the forms of violence in the Family Violence Protection Act 2008 (Vic) (outlined above) and which relate broadly to the data items listed below. There are other forms of family violence which are not included in the brief examples below, such as stalking (including through use of technology or social media) and theft.

Physical abuse

Physical abuse refers to abuse involving the use of physical force against another person. Physically abusive behaviours can include shoving, hitting, slapping, shaking, throwing, punching, biting, burning, strangling or poisoning, including use of weapons or objects to cause physical harm.24 It can also include lack of consideration for a victim’s physical comfort or safety (such as dangerous driving). Some acts are physically abusive even if they do not result in physical injury.

Sexual abuse

Sexual abuse refers to forcing a person to engage in sexual activity.25 Sexual abuse can include rape, forcing a person to perform sexual acts, causing a person pain during sex without their consent, and forcing a person to watch pornography. Being pressured to agree to sex, unwanted touching of sexual or private parts, causing injury to the victim’s sexual organs are all examples of sexual abuse. Sexual abuse includes sexualised behaviours towards an adult or child, such as talking in a sexually explicit way, sending sexual messages or emails, exposing to sexual acts, having a person pose or perform in a sexual manner when they do not want to, or are unable to consent to do so.

Emotional / psychological abuse

The FVPA defines emotional or psychological abuse as a behaviour that torments, intimidates, harasses or is offensive to another person. Emotional abuse refers to ‘abuse that occurs when a person is subjected to behaviours or action (often repeatedly) aimed at preventing or controlling their behaviour, with the intent to cause them emotional harm or harm through manipulation, isolation or intimidation.26 Any form of behavior that deliberately undermines the victims confidence, acts to humiliate, degrade or demean the victim. This includes threats to the person or their friends or family, or for a perpetrator to threaten to commit suicide or self harm. Silence and withdrawal are also means of abuse.