Key findings

- Attracting staff with the appropriate skills and experience in working with people who use violence was a particular challenge for some cohort trial and case management providers.

- A number of providers reported that the initial 12 month funding allocation for the new community-based interventions made implementation challenging. This particularly impacted on staff recruitment and attrition.

- There appears to be some confusion regarding eligibility for the programs, particularly related to their voluntary nature (as opposed to being mandated via courts or Child Protection).

- There are some challenges to effective service coordination across the sector, including a lack of capacity or willingness to work with people who use violence.

- Performance management of the programs needs to be strengthened, to ensure there is accountability for intended outcomes, and consistent data collection and reporting.

- There were examples of underspend among cohort intervention trials, including large proportions relative to the total funding amount.

7.1 Introduction

This chapter examines the activities and processes that were involved in establishing the cohort trials and case management. This includes the following aspects:

- Workforce and training – the ability to recruit and train the workforce required to deliver the programs

- Referrals and service coordination – the processes for generating referrals to the programs, and providing access to other services across the broader service system

- Funding and timelines – an assessment of the funding and timeframes for program delivery.

- Governance and communication – the formal governance mechanisms and communication processes between FSV and providers

7.2 Fidelity of implementation

Fidelity explains the extent to which a program was implemented as it was prescribed in the original protocol or as it was intended by the initiative developers (Proctor, et al. 2010). Fidelity considers adherence to the program protocol, dose/quantity of the program delivered, and quality of the program delivered. Changes to program design and implementation are not in and of themselves negative. Rather, they may reflect appropriate adaptations to a model or program based on the maturity of implementation to reflect learnings.

Case management was generally implemented as intended. Over the course of implementation, the main adaptations made related to increasing use of brokerage (discussed in 4.5.1) as providers became more confident and familiar with how to use brokerage, and flexibility with the sessions provided. Numbers of sessions depended on the needs of the person who used violence. Where someone needed more sessions than the up to 20 allocated per person, this was offset by appropriate underutilisation by other participants (where their needs had been met after fewer than 20 sessions).

Small adaptations were made to the cohort intervention trials as they were rolled out, particularly for the two trials working with Aboriginal clients. BDAC increased the number of sessions to 15 (up from 12), upon recognising that the quantity of content that needed to be covered required more sessions than initially designed. Further, recognising the need for continued support post-program, a fortnightly yarning circle has been established for the exiting participants to continue in post-program. The change made in the Better Ways program is quite different to BDAC, in that it relates to the intake criteria. Previously the criteria was for fathers to have some contact with child or mother. Upon realising this was a barrier to accessing support, particularly for Aboriginal fathers, this intake criteria was relaxed. In both these instances, adaptations made were appropriate iterations of the program design to respond to participant needs. Additionally, the program for people with a cognitive impairment delivered by Bethany was changed to a ‘semi-open’ group whereby participant intake occurred at certain points throughout the program delivery timeframe. This change was made in order to increase the number of participants that could access the program, as there was lower than anticipated program engagement and completion in the first round of program delivery.

In two instances, partnerships between providers have broken-down, representing a change from the model as intended. This involved BDAC and the Centre for Non-Violence, and Drummond Street with On The Line and Merri Health.

The cohort trial program that had the greatest level of change to what had been intended was the program delivered by Drummond Street. This included no longer delivering a telephone support service as had been intended in the model design. This was because, following initial contact with the client cohort, Drummond St deemed that the level of complexity of the issues they were experiencing deemed it inappropriate to undertake a phone response at this point. This program also adapted its program focus in the second year of funding to offer a program for women who use force, as well as embed the program for LGBTI clients within the provider’s ‘Queer Space’ service, which offers an integrated service response.

7.3 Workforce and training

The family violence sector in Victoria is currently undergoing a period of significant reform, with a number of new initiatives and ways of working being developed and implemented (i.e. family violence and child information sharing information sharing scheme, MARAM and the introduction of the Orange Door). There is also a greater level of demand for services than has been experienced by the system ever before. These system-level factors have had direct implications in terms of the ability of service providers to recruit and train case workers to respond to the complex circumstances of many of the clients in the perpetrator case management and cohort trials.

7.3.1 Recruitment

Attracting staff with the appropriate skills and experience in working with people who use violence was a particular challenge for some cohort trial and case management providers. While some providers were able to recruit highly qualified staff without difficulty, others were required to advertise multiple times to attract a suitable candidate.

Challenges with recruitment were largely due to a shortage of qualified staff, particularly in regional areas. The reasons for this include:

- Competition for resources across the sector, which is particularly heightened in rural areas. There are a limited number of case workers and program facilitators who have experience working in the perpetrator context, particularly compared to the victim/survivor case management workforce. This can be partly explained by the limited funding invested in perpetrator programs historically, compared with victim support programs.

- There are a limited number of case workers and program facilitators with specialised experience in working with the identified target cohorts, which was a specific feature of the program design in some cases, e.g. for CALD, Aboriginal and LGBTI groups.

In some cases this was reported to have led to lengthy recruitment processes which contributed to delays to the program start dates. In circumstances where there were no suitably qualified applicants for the role, a culturally appropriate applicant was hired and subsequently trained in working with people who use violence.

Reflecting the broader need to build workforce capacity across the family violence sector, to respond to the increasing demand for services, there is work taking place to address this through the State Government’s Building from Strength: 10-year Industry Plan for Family Violence Prevention and response. This includes a significant funding grant provided to No To Violence to develop more programs and provide training across the sector, including increasing the number of family violence subjects offered at TAFE institutions. These programs will include building capacity in more specific areas of practice, such as working with people who have AOD and Mental Health issues, and Aboriginal clients. Additionally, FSV is funding a select number of places in the Graduate Certificate in Client Assessment and Case Management offered at Swinburne University, which is a specialist course for working with men who use violence.

Case study

One cohort trial provider for Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal fathers was seeking to hire a staff member from the local Aboriginal community. However, there were a number of features that made this role unattractive to a candidate which included:

- the short tenure of the contract

- the 0.6 FTE position

- the abundance of other opportunities available for Aboriginal personnel working in this field.

To overcome the negative aspects of the job description, this cohort trial provider organised a secondment position for the successful applicant, which provided them with job security, while filling the cohort trial role.

Additionally, the timing and length of the trial contributed to recruitment challenges for a number of the providers. Delays to the initial release of funding for the programs resulted in providers recruiting for staff in late 2018 or early 2019 with short contract tenure. This was exacerbated by the uncertainty of further funding beyond June 2019, which led to staff attrition at some service providers due to job insecurity. There were some instances where this had flow on impacts for clients, particularly where a number of the program staff left towards the end of the program. Clients said in interviews that they were disappointed to lose the relationship they had built with their case worker.

7.3.2 Training

Providers of both case management and cohort trials invested time and funding into training staff. This has predominantly been done out of necessity to ensure staff were appropriately qualified to be working with people who use violence.

7.3.2.1 Cohort trial training

There is one short course offered in Victoria that qualifies workers to facilitate intervention groups for people who use violence. This course is run by No To Violence. It is a two-day course designed to support community sector workers with clients who use male family violence. Given the time commitment required to complete this course, it is a significant investment for staff and service providers.

In addition to accessing the external training, a number of cohort trial providers delivered additional training specific to their delivery model, or contacted external trainers for this purpose. Two cohort trial providers flew experts in their chosen model from the United States to deliver training to program delivery staff. These experts were specialised in the ‘Vista’ model and the ‘Keeping families together’ model. Following this initial training, these experts where then kept engaged throughout the delivery of the program, including providing supervision support to on the ground staff in some cases. Another service provider paid external consultants to provide training and supervision.

Individual cohort trial providers also provided internal training for recruited staff, such as orientation programs and trauma informed approach training.

7.3.2.2 Case management training

Specific training in individual case management models for people who use violence appear to be more limited, and a number of providers expressed a need for the development of more materials in this space. It was mentioned that Relationships Australia have developed an internal training program which would be beneficial for other case management providers to have access to. Another provider suggested that extra training could be provided by DHHS. Furthermore, one case management provider mentioned that they were currently in the process of setting up a Community of Practice of people working with people who use violence, in order to share learnings across the sector.

Although the investment in staff training has been made by individual providers, it will have a broader impact on sector’s capability to deliver interventions for people who use violence. A larger impact of these trials on the broader family violence system in Victoria is that more case workers are being upskilled in working with these cohorts. This is increasing workforce capacity and capability in the system, and setting the ground work for this type of service to expand.

7.4 Referrals and service coordination

7.4.1 Referrals

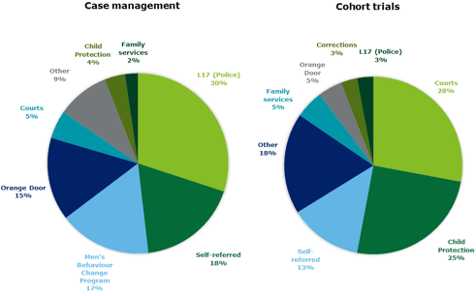

Both cohort trial providers and case management providers received referrals from a variety of sources. The most common sources of referrals, as reported via the data collection tool were via L17s for case management and from courts for the cohort trials. The referrals sources are shown in Chart 7.1.

Chart 7.1 Referral sources

7.4.1.1 Third party referrals

Unexpectedly, a high number of referrals to the cohort trials came from the courts and Child Protection. Unlike in the justice context, participation in the community-based trial programs is voluntary, and therefore an individual cannot technically be mandated to attend via a court order. It was however reported by a number of providers that Magistrates were recommending attendance at a MBCP as part of a FVIO, which resulted in either direct or indirect referral to a cohort trial or case management. This then led to a perception that clients were ‘mandated’ to attend in order to meet the requirements of their FVIO.

The provider delivering to CALD cohorts specifically engaged with the Magistrate at the court in their area, in order to generate awareness for their program and request referrals for people who were on a FVIO. This was to ensure these men would receive a culturally appropriate intervention. Subsequently, 30 of the 48 people who use violence presented in the data collection tool for this program had been referred via the court.

It was clear from interviews with people who use violence that they were not always aware of the difference between voluntary and mandated attendance when referred from courts and Child Protection. Some participants indicated that the program was recommended to them by a third party, e.g. a DHHS case worker or their lawyer, however they acknowledged that involvement in the program was ultimately their choice.

I wasn’t told by anybody to go there. I voluntarily accepted what [the provider was] saying when I rung that number, and I said okay, well yeah, that seems like I might need that sort of guidance… I didn’t get forced to do it.

With a lot of the programs like that, a lot of the people - that's the first thing I say: "I'm forced to do it, either by law or DHS or the courts or whatever." The way I see it, you might be recommended by a court to do a program, but no-one's forcing you to do it. It's up to you to show up… no one is making you stay.

Other participants talked of being ‘required’ to participate, or being ‘ordered’ or ‘told’ to participate in the program. This was particularly evident when the program was recommended to participants involved in legal proceedings. This type of referral is considered to be “service mandated”, despite the fact the individual is not technically mandated to attend.

I’ve just come out of like a court case for like drug use and breaches of intervention orders, so then as part of that been told I had to do this men’s behaviour change program…It was a compulsory requirement.

It was an agreement through Family Court, Federal Court to do that… they asked me just to do a men's behavioural change [program]…It was basically a negotiation between two lawyers, and they asked me to do something...

Providers commented that where a person was ‘service mandated’ they tended to be more resistant initially to participating in the service, as they had not made a choice to be there. Additionally, the engagement of those who are ‘socially mandated’ can depend on the status of their relationship with the person who experiences violence, and whether they believe reconciliation is possible. Despite this, providers reported that where they persisted in building the relationship and trust with these individuals, instead of ‘giving up’ on them, there were instances where they noticed a shift in thinking, and engagement became more genuine. This demonstrates a shift from pre-contemplative to contemplative engagement.

Case study

An Aboriginal person was reportedly ‘mandated’ to attend the cohort trial. They were a respondent to an IVO, and if breached this would have serious implications for their work in the community. During their participation in the cohort trial, the service provider noticed significant progress. This progress included the cessation of text message contact with the partner who implemented the IVO, and beginning to prioritise self-care (which is something they had never previously done). When they were required to go back to court they took a letter of support from the cohort trial provider. This resulted in a non-conviction in court. They were able to avoid the IVO having an impact on their work in the future.

FSV is reportedly undertaking communication with referral agencies as well as the Department of Justice and Community Safety in order to clarify the voluntary nature of the programs, and to provide further guidance on the conditions for referrals and participation in the programs. This is required in order to ensure there is a consistent process for accepting referrals across all the programs. This also has implications for the interface with the justice-based programs, and the consistency of the referral pathways across the two sets of programs. The complexity of the perpetrator cohort, and the large number of referrals from the justice sector, means that it is rarely a straightforward decision that an individual would be purely ‘community-based’. Interaction with the courts and Child Protection is going to be a factor in a significant number of cases, and therefore should not be a factor which limits their eligibility to participate in a program. There is an opportunity to streamline the referral process across the community and justice sectors, so that people who use violence are able to access the most appropriate program for their individual circumstance, regardless of the referral source.

7.4.1.2 Self-referrals

There are a substantial number of self-referrals being reported via the data collection tool. When this was discussed with providers, both cohort trial providers and case management providers indicated that it is rare for an individual to refer themselves as a means of self-motivation to change their behaviour. Conversely, when a person does refer themselves, it is most often the case that there is an external motivation, such as pressure from a family member or lawyer, as discussed in Section 6.2. Interviews with clients indicated that often these self-referrals were made following an incident of violence. This type of referral is considered to be ‘socially mandated’ – that is that there is an acknowledgement that their attendance is voluntary, however there is a known consequence, either legally or otherwise, if they do not attend.

You have to make the decision yourself. So after my incident, I put my hand up and I said yes. On this occasion, yes, I was in the wrong. I’m willing to wear what I’ve done. I’m willing to take part in the [Program name]. So I’m now taking part in [Program name]. The facilitator’s name is [Facilitator name].

And I thought, well I’ve lost my partner of six years. I’ve lost my job. I’m like, I need the support. I need the focus on things. I need to get my life into order in order to make everything work. And so I contacted a number of companies. I can’t exactly remember what ones they were. And then they referred me to [Provider], which then [Case Worker] gave me a call back and we eventually had a meeting. And yeah, I asked her to help me with some sort of group in changing my behaviour and everything else. And it went from there.

People who use violence reported that when they self-referred, they searched online for perpetrator programs, and then contacted the provider directly. However, no participants reported being aware of the unique nature of the cohort or case management trials. Rather, awareness was limited to knowing the provider offered a ‘men’s behaviour change’ program.

I went into the program on a voluntary basis. I did not go through a court order which a lot of the men are there in court orders… I found it online and pretty much put my name down to see if I could get some counselling and also see if I could get into a program which would help me with my communication.

7.4.1.3 Intra-organisational referrals

While there were instances where referrals were made directly to the cohort trial or case management program itself, most often referring agencies would make a referral to the organisation more generally, who would then assess the individual as suitable for the specific program. IRIS data shows that “internal from this agency” referrals make up 12% of referrals for the cohort trials and 12% of referrals for case management. This process is important for identifying individual needs which deem the individual suitable for a cohort trial rather than a mainstream MBCP, and assessing the readiness of the referred person for group work or individual case management.

A few people who used violence had prior or ongoing engagement with the provider delivering the program. In such instances, provider staff identified the participant as a suitable candidate for the program. Participants engaged through this approach reported that it was a straightforward process.

It was quite good… I was already doing drug and alcohol with [Provider] and then they wanted me to also do this course… So, by the time I’ve already done them courses and continued on with drug and alcohol, they rang me.

Cohort trial providers that also run services for people who experience violence also referred persons who use violence through these connections.

7.4.1.4 Timeliness of referrals

Stakeholders highlighted that that there is a window of opportunity between violence occurring and service intervention, which maximises the likelihood of engagement. This demonstrates the importance of timely referrals.

Case management providers found that being present at the courts, and therefore having face to face contact with the person who uses violence, was an effective engagement strategy. Providers explained that, in their experience, the point at which someone is required to present at court is the point they have the highest level of motivation to ‘do something’ about their violence.

Another case management provider utilised automated text messages to ensure that timely contact was made with people who use violence following an L17 report. They found that this led to increased responsiveness.

Participants reported that a common way they accessed the intervention was through receiving direct contact from the program provider shortly after the family violence incident. This contact reportedly followed an incident that required police presence. Some participants mentioned that they had received a text message or letter directing them to contact the provider, whereas others recounted that they had received a phone call directly from the provider.

When I have the trouble with the police and the court guys and all that, I didn’t wait long to see the help… The police sent a letter here… The police referred for the – on the letter… to three different places or something like that.

[The police] sent a text message through two days after the incident to say that [Provider] would be contacting me. Then yeah, within a day, I was contacted. I was contacted the same week the incident happened.

There was some confusion expressed by participants who were referred to programs in this way, particularly when compared to participants who had a Child Protection worker or legal representative available to explain the process. Participants noted that they were somewhat unsure as to what the content or purpose of the program was until they were able to meet with provider staff. The need to offer a more comprehensive explanation of the program was highlighted by some participants.

It needs to be a face-to-face meeting for someone to explain that it's okay to be in that room and it's okay to take up that space… Once you talk to the people you go, ‘oh, my god, this is where I need to be’.

After being marched into a police station to do a statement… two days after, a message came through on my phone, which I knew nothing about. I just knew it came from Vic Police, blah, blah, blah... And [there was] a phone number. And I didn’t know what I was supposed to do with it, so thought I’d give it a call.

7.4.1.5 Common barriers to referral

There were a number of barriers to referral raised by providers of the case management and cohort trials. These barriers were sometimes isolated to certain locations or providers, however there were some common themes identified across providers which are outlined below.

Criteria not to work with individuals on bail or on community corrections orders (CCOs)

A common concern of case management providers was that they were unable to accept referrals for people who use violence who were on CCOs or on bail, as the program could not be mandated, and there is no justice sector equivalent. Case management providers saw a need for case management within this group of people where their needs are not being met, for example as preparation for involvement in a group program. As described above, this distinction between mandated and voluntary referrals was not consistent across providers, particularly for the cohort trials. One provider staff member commented:

One of the complications – it is very clearly targeted at voluntary participants. But some might start off as voluntary and become mandated. It’s not something we can easily predict. And if we had a mandated person with cognitive impairment, it would be remiss if we didn’t include them.

Program awareness and understanding

There was reportedly inconsistency across the service system regarding awareness of the new community-based interventions, and an understanding of their intent, which impacted on the number of referrals in some cases. Particularly, there was a lower than anticipated number of referrals from Orange Doors. The Orange Door reform is still in early stages of implementation, with a number of processes still being worked through. An evaluation of the Orange Door implementation is currently underway.

In some regions, it was identified that the Orange Door had little awareness of the cohort trial being delivered in their area. It is possible that this lack of awareness reflects the early stages of implementation of both the pilot programs and the Orange Door. In areas where the organisation had an established relationship with the Orange Door, particularly in geographically smaller regions such as Barwon, this issue was less notable, and referrals from the Orange Door were common.

Misidentification of the primary aggressor

For providers delivering services to women who use force and LGBTI clients, including in the case management context, misidentification of the primary aggressor was sometimes noted as an issue in the referral process. In some cases, it was reported that there was a misidentification in L17s as to the nature of the perpetration of violence, and therefore who is identified as the primary aggressor. This would result in individuals coming into programs being named as the ‘perpetrator’, whereas the assessment process would subsequently identify them as a person who experiences violence. Related to this is a hesitance by some legal services to refer clients to these programs due to the risk of misidentification. Particularly for LGBTI clients, this carries a significant risk of re-traumatisation if there is a history of discrimination and isolation within the service system. Further education is required to prevent misidentification of the primary aggressor, which further persecutes individuals who are experiencing trauma.

7.4.2 System level factors

A secondary objective of the new community-based interventions is to facilitate referrals to other community-based programs, in order to address participant’s needs which may be related to their offending behaviour or impacting on theirs or their family’s lives.

Results from the data collection tool show the proportion of participants referred to other services, the total number of referrals, and the most common referrals. This is summarised in Figure 7.1.

Figure 7.1 Referrals to other services

| Case management | Cohort trials | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

At least 252 participants were referred to one or more programs 182 not referred, |

There are a total of 401 referrals to other programs |

At least 35 participants were referred to one or more programs 88 not referred, |

There are a total of 61 referrals to other programs |

|

Top 4 most common referrals

|

Top 4 most common referrals

|

Source: Deloitte Access Economics data collection tool

Referrals across each of the cohort groups, for participants in both the cohort trials and case management, were analysed to determine if there were any differences in the nature of the referrals being made. Table 7‑1 presents the top two service system referrals reported for each cohort.

Table 7‑1 Referrals out – cohort specific

|

Cohort |

Top two referral types |

|

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander |

|

|

Fathers |

|

|

Women who use force |

|

|

CALD |

|

|

Cognitive Impairment |

|

|

LGBTI |

|

There were a number of considerations providers had to make when referring participants to external community services. These are outlined in the following sections and indicate that further education activities are required to ensure that holistic and equitable access to services can be provided to all individuals in need of assistance.

7.4.2.1 Reluctance to provide services to people who use violence

There was a level of apprehension among some external organisations about providing services to perpetrators of family violence. For example, one provider explained that “the minute you say that you want to refer a man who has used family violence, workers become apprehensive”.

Gender appeared to be a factor in this response. Staff from the trial for women who use force stated that external service providers were accepting of their program, and open to providing other supports to participants. This difference in acceptability of services based on gender was confirmed by the consult with the provider of the LGBTI cohort trial. This provider had noticed that a client’s degree of ‘femininity’ (as perceived by external service providers) affected their ability to be accepted for other service support.

7.4.2.2 Negative experiences with services

The nature of the cohort trials being targeting people typically from a vulnerable background, means that these individuals often have previous experiences of trauma, discrimination, and institutionalisation. This has contributed to mistrust of community services and government agencies in many cases. For example, it was reported that perceived discrimination, and in some cases, past negative experiences with police or ambulance services, meant clients would not call the police or ambulance even when they required their services. When providers of the cohort trials and case management first reach out to these people, it is sometimes the first contact they have had with a service, due to their past experiences and isolation from the system. Before being able to refer them onto other related services, the staff must work with these individuals to build their trust. This means providers are sometimes required to address past failings of the broader service system, creating additional burden on staff.

7.4.2.3 Appropriate services in the context of family violence

Stakeholders raised the importance of using counselling or other services appropriately in the context of family violence. It is important that the individuals working with people who use violence are trained in identifying and avoiding collusion. For this reason, providers were hesitant to refer individuals to external services unless they had a trusted relationship with the provider, or knew that they had experience providing services in the family violence context. It is also important to recognise the context of the person’s entire family unit, and the services that are being provided to their partner or children, to ensure that there is alignment and that a comprehensive risk assessment has been undertaken to understand the level of service required. The recent implementation of the Family Violence Information Sharing initiative will assist in providing this ‘complete picture’ of the context of both the person who uses violence and the person who experiences violence, including the level of risk and associated need.

7.4.2.4 Gaps in available services

A lack of housing services was reported to be the largest gap in the service system for people who use and experience family violence. It was consistently reported by both case management providers and providers of cohort trials that it was extremely difficult to find temporary accommodation for their clients.

An example was provided of one temporary accommodation option for men who use violence in the western suburbs of Melbourne, where police are able to admit them for one night. However, this one service was insufficient to meet demand. Service providers reported that the lack of available accommodation services for people who use violence acts as a disincentive for these individuals to leave the living situation in which they are perpetrating violence.

Supporting this finding was that case management brokerage funding was often spent on accommodation. Case management providers reported that brokerage would pay for three nights of accommodation, however following this, these individuals would often have nowhere else to go, and would return to the family home.

7.4.3 Community outreach

Both case management and cohort trial providers reported to have spent time undertaking outreach and educational work with other service providers and the community, and indicated that this was an important aspect of their work to promote referrals. For some providers this has been a more necessary focus of the work than for others, depending on the referral pathways in the local area. For example, noting some of the unanticipated difficulties generating referrals from the Orange Door in certain regions, providers in these areas have had to undertake a greater level of outreach to account for this.

Each provider came up with their own approach to community education. For example, one case management provider prepared a script on why they offer support and why people who use violence are deserving of a case management service. Another case management provider developed brochures and spoke at community forums about the service they offer.

The effort that providers invested in outreach work appeared to depend on how established they were as a perpetrator intervention provider. For example, one case management provider who had not delivered case management for people who use violence previously explained that they had put a lot of effort into building relationships with potential referral sources. Whereas another case management provider commented that they already had links within the community, and that networking activity had already been established by the time the case manager commenced their role.

Outreach work was particularly important for providers of Aboriginal case management. This is because they needed to establish trust in the communities in which they work. Aboriginal case management providers particularly made an effort to engage with ACCOs. They also spent time attending cultural groups and noted that if people in the community don’t know you, they won’t feel comfortable engaging with you. Similarly, the LGBTI cohort trial provider gained strong traction with the community through putting out fliers and recruiting staff belonging to the community.

7.5 Funding and timelines

7.5.1 Funding timelines

A number of cohort trial providers reported that the initial 12 month funding allocation for the new community-based interventions made implementation challenging. The timeframe created a feeling of ‘being rushed’, as there was a large amount of work to establish the program within the one-year period. These activities included:

- deeveloping the trial

- establishing governance

- recruiting staff

- attracting clients

- data collection.

This challenge was exacerbated by delays to the initial funding availability, which was delivered in late August as opposed to July. This gave staff limited time to train and familiarise themselves with the delivery models prior to working with clients. Additionally, providers of cohort trials for Aboriginal men who use violence found that one year was not enough time to gain trust with the local Aboriginal community.

Providers highlighted that changing violent behaviour is a long-term process, which requires long term intervention. Many service providers commented on the limitations of what outcomes could be expected over a one-year trial timeframe. Providers had observed early signs of change in participants, however they would have liked more certainty regarding funding over a longer time period, in order to establish more robust mechanisms for measuring program success.

As of the date of this report, funding for cohort trial providers has been extended for an additional year, ending 30 June 2020, and funding for case management has been made ongoing except for brokerage funding.

Despite this positive outcome, the significant delays to the funding announcement meant that there were implications for delivery of the programs. The most commonly reported impact was staff leaving due to the uncertainty of ongoing work. Retaining staff during this period of funding uncertainty was a challenge for providers, with one cohort trial indicating they had a large number of staff resignations in the months approaching July 2019. Staff turnover leads to the necessary process of re-training staff and rebuilding trust with the cohort trial community. Providers highlighted the importance of having long term staff for the success of their work.

7.5.2 Funding amount

Five out of seven cohort trial providers underspent their budget in the 2018/19 financial year. Underspend ranged from $64,818 to $509,384. When asked about this in consultation, providers noted that the delays to receiving the initial funding allocation, and the subsequent condensed timeframe in which to implement the programs, was a factor in the inability to acquit all funds.

Without specific funding for these programs, they would cease to operate. This would mean people who use violence from these target cohorts would only have the option of attending mainstream MBCPs which are not always appropriate to their needs.

During the evaluation, it was determined that a number of the case management providers had still not recruited into the case manager role after more than twelve months, which meant that their funding remained unspent, and no clients had been engaged. There was inconsistency in how this was being reported to FSV and the APSS, and therefore at times limited awareness as to the nature and extent of this problem, including where funding remained unused. Additionally, participation in the evaluation has been mixed, despite being a requirement of the provider funding agreements, and there have been no consequences for providers who failed to respond.

7.6 Governance and communications

7.6.1 Provider forums and advisory group

Family Safety Victoria facilitated four governance forums for the new community-based perpetrator inventions and case management. These were:

- perpetrator Interventions Advisory Group –to oversee the implementation of the case management and cohort trials, by reviewing progress, challenges, and improving an understanding of program approaches and strategic implications[3]

- cohort trials provider forums – to guide and oversee the implementation of the seven perpetrator intervention trials, by providing implementation updates and a forum to discuss common challenges [4]

- case management provider forums - to guide and oversee the implementation of the case management, by providing implementation updates and a forum to discuss common challenges[5]

- Aboriginal provider forums – as above, for all providers delivering services to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who use violence.

These forums are generally considered to be an effective mechanism for FSV to maintain a level of oversight of the programs, communicate with providers, and for providers to give updates regarding their programs. This also has the added benefit of providers being able to share learnings among one another of what is working, and what are common barriers to success. This is particularly important in a context where these programs are a new and innovative initiative within the family violence system, and therefore it is important that there is a mechanism to share experiences, build effective and consistent approaches, and contribute to a community of practice for improving service delivery in this space.

The Perpetrator Interventions Advisory Group includes representatives from across government who are involved in the delivery of services to people who use and experience violence. This forum is an effective mechanism to collaborate and share learnings within and across different sectors, such as Corrections and courts. Subject matter experts from family violence peak bodies are also able to share their expertise in this forum, and contribute to best practice approaches for program development and delivery.

7.6.2 Working relationship between FSV and perpetrator intervention providers

Overall, the relationship between FSV and the providers of the new community-based interventions was considered appropriate. Service providers reported varying levels of communication with FSV, however there was a common view that they could access assistance or information when required.

Although the overall relationship with FSV was appropriate, there were two logistical issues were barriers identified:

- the timing of the funding announcement and release (as mentioned above).

- performance management.

Data collection and monitoring, particularly for pilot programs, is fundamental for accountability and performance management. Now that the programs are past the initial establishment and implementation phase, some providers have begun to prioritise data collection and performance monitoring processes internally within their organisation. While providers are required to report against their individual KPIs and targets to the local APSS, there is not a consistent approach to outcome reporting across the programs. Additionally, a number of service providers reported difficulty installing and using the IRIS software, which was intended to serve the function of recording participant data. A data collection tool was developed as part of this evaluation to overcome this issue. However, with the evaluation concluding in November 2019, a longer-term solution is now required for outcome reporting.

More established processes for provider management are needed, including further clarification with providers of the roles and responsibilities between FSV and the APSS.

[1] Cohort too small to report further

[2] All responses tied. Cohort too small to distinguish ranking

[3] Family Safety Victoria (2018). Terms of Reference - Community Based Perpetrator Intervention Trials – Perpetrator Intervention Trials Advisory Group

[4] Family Safety Victoria (2018). Terms of Reference - Community Based Perpetrator Intervention Trials – Providers Forum

[5] Family Safety Victoria (2018). Terms of Reference - Community Based Perpetrator Intervention Trials – Case management Forum

Updated