Who is accessing The Orange Door network for assistance?

The Orange Door network aims to be responsive and accessible for all, and inclusive of individuals of all ages, genders, abilities, sexes, sexual orientations, cultures and religions. The establishment and operations for The Orange Door network has been informed by Everybody Matters: Inclusion and Equity Statement (Everybody Matters), published by the Victorian Government in April 2019. Everybody Matters articulates a 10-year commitment to building an inclusive, safe, responsive and accountable family violence system for all Victorians. The statement calls out the need to address the barriers that people from a diverse range of communities’ face, when reporting family violence and when seeking or obtaining help.[11]

The Orange Door network recognises that people can face additional barriers to getting the help they need, due to systemic or structural discrimination. The Orange Door Inclusion Action Plan was released in 2021 and is intended to enhance inclusion, access, and equity across The Orange Door network. The Plan was developed with partner agencies and sets out how The Orange Door network will ensure services are accessible for all clients and offer supports tailored to individual needs and experiences. The Plan outlines a series of actions aimed at achieving inclusion, including through the physical environment, leadership, communication, training, and connection with local communities.

With statewide establishment of The Orange Door network, ongoing implementation of the Inclusion Action Plan will continue to support The Orange Door network in responding to Victorian communities and meeting their diverse cultural and social needs.

How many people has The Orange Door network sought to support?

Noting that a single referral may involve numerous individuals (such as members of a family), in 2021-22, nearly 130,000 people including approximately 55,000 children and young people (including unborn children) were referred to The Orange Door network and provided with a response.[12] Compared to 2020-21, this represented a 68.3% increase in the total number of people and an 80.6% increase in the number of children and young people provided with a response. This is consistent with the growth in referrals to The Orange Door network and can be attributed to the continued expansion of the network over the period.

Children and young people represented 42.3% of all people provided with a response in 2021-22, increasing from 39.4% in 2020-21.

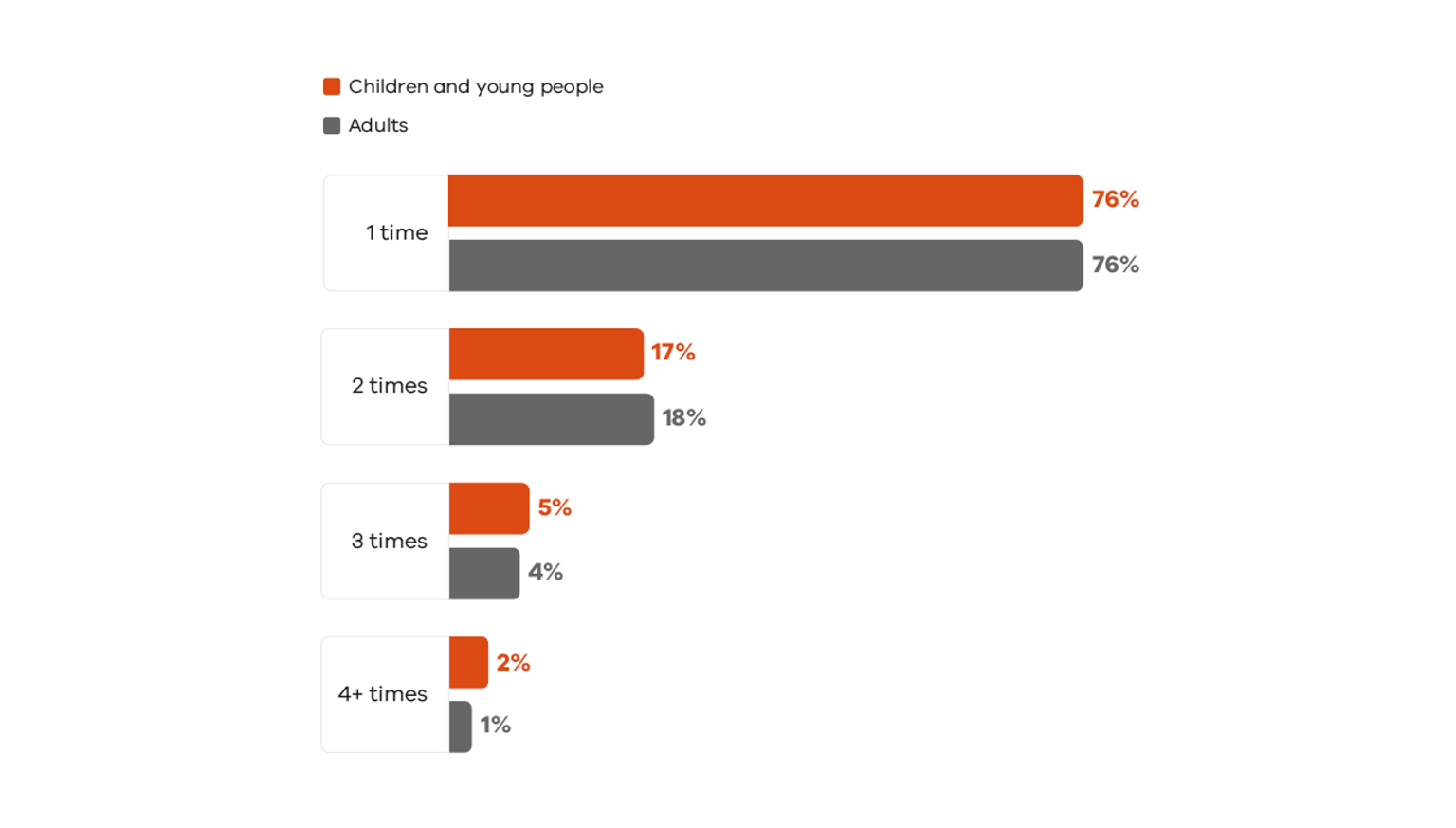

Individuals and families can seek assistance from The Orange Door network as many times as they need. In 2021-22, 21.6% of people who received a response from The Orange Door network were referred or sought assistance two or more times during the financial year. Children, young people and adults displayed a similar pattern in the number of times they were referred or sought support from The Orange Door network (Figure 9).

Working with people from diverse communities

The Orange Door network is welcoming to people of any age, gender, ability, sex, sexuality, ethnicity, culture or religion. People from diverse communities are offered safe service responses through The Orange Door network where their cultural and religious and other preferences and specific needs are respected.

In 2021-22, almost three in five adults (58.0%) who were provided a response from The Orange Door network identified as female compared to 40.4% who identified as male and 0.1% who self-described their gender identity. For children and young people, 46.5% identified as female, 48.1% identified as male and 0.2% self-described their gender identity.

The collection of data about language spoken at home and disability status is improving as is data about country of birth, sexual orientation and gender identity. Improvements in demographic data collection by practitioners remains an area of focus and will be monitored through The Orange Door Performance Framework.

Enhancements to The Orange Door network CRM in the next financial year will focus on increasing the quality and quantity of data collection on diverse communities with an emphasis on CALD and LGBTIQA+ communities and clients with a disability.

The Orange Door network is being supported to implement the Inclusion Action Plan, which sets out how The Orange Door network will ensure services are accessible for all clients and offer supports tailored to individual needs and experiences. This will enable effective programs and activities to be replicated and scaled-up across The Orange Door network and further contribute to the provision of inclusive, responsive and accessible family violence and sexual assault support for all Victorians.

In addition, a range of capacity development initiatives for frontline workers have been planned and conducted across the network. These initiatives include building and embedding culturally responsive practice, trialling deaf awareness and cultural competency training, supporting the workforce to engage with language and translation services and a pilot mentoring program to support LGBTIQA+ understanding and capacity across The Orange Door network.

New initiatives have also commenced that will impact the accessibility of The Orange Door network. They focus on strengthening:

- partnerships across sectors to improve the family violence and sexual assault support to Victoria’s multicultural communities

- the family violence and sexual assault service systems to better respond to children, young people and adults with disabilities at risk of family violence, and to strengthen linkages and referral pathways with disability and other community-based services in a local area.

Rani, Mala and Harshad: cultural safety as part of the family violence response[13]

Rani and Mala were referred to The Orange Door network by Child Protection, who indicated the mother and baby were experiencing family violence from husband and father Harshad. The family were isolated in regional Victoria, and Rani was on a restricted visa prohibiting her from both employment and access to government benefits.

Child Protection referred the family to The Orange Door network so that on one hand Rani and Mala could access comprehensive safety planning, and on the other, Harshad could be engaged in an in-language behaviour change program.

When The Orange Door network received the referral, Rani and Harshad were assigned separate practitioners working in the same integrated team. Both practitioners ensured an interpreter was used for each engagement. Throughout The Orange Door involvement, the two practitioners collaborated with each other and with Child Protection to share information and risk assessments. The practitioners also consulted with a multicultural service to ensure their assessments and decision-making was culturally appropriate and safe.

Rani disclosed that after experiencing violence and abuse over three years, she had separated from Harshad and moved in with his family, following an agreement that Harshad would not attend the new home. However, due to the family controlling her and monitoring her movements, Rani decided to return to Harshad. Since the return, Harshad had been emotionally abusive and limited Rani’s ability to care for Mala. Nonetheless, Rani wanted to remain with Harshad until she was able to return to her home country.

One practitioner completed a risk assessment and safety plan that included safety measures if the family violence risk escalated, as well as planning for Rani and Mala to return to their home country. Rani and Mala were referred to maternal health care to provide additional support for their wellbeing.

Another practitioner engaged with Harshad who said he was trying to be a better father and husband but understood he had been controlling towards Rani. Harshad also disclosed he had experienced abuse from his family as a child and that he wanted to learn how to behave in non-violent ways.

The practitioner completed a family violence risk assessment with Harshad, as well as a safety plan so that he had immediate strategies to modify his behaviour in situations where he would normally use violence or control. Harshad also agreed to be referred to an in-language behaviour change intervention.

The Orange Door and Child Protection continued to collaborate and support the family, while they remained in the country. Harshad engaged with the in-language behaviour change intervention and was observed to be responding to Mala’s needs and supportive of Rani. The Orange Door worked in collaboration with Child Protection to arrange transport and flights for Rani and Mala, and then referred Rani and Mala to family violence support services back in their hometown.

Supporting Aboriginal self-determination

Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations or ACCOs are critical partners in The Orange Door network. They receive funding to employ an Aboriginal Practice Leader and Aboriginal hub practitioners to ensure that Aboriginal people receive a culturally safe response. In addition, ACCOs support the establishment of the Aboriginal Advisory Group which involves community members, the Dhelk Dja coordinators and other ACCOs to ensure a culturally safe response and strong connections with local services.

State-wide funding provided to ACCOs increased in 2021-22 to enable ACCOs to expand their practitioner workforce in The Orange Door and provide flexible brokerage to Aboriginal clients. This contributed towards the employment of additional staff dedicated to the delivery of Aboriginal services in addition to other funding associated with the commencement of seven The Orange Door areas over the period.

FSV is working with ACCOs to develop additional cultural safety training to be tailored to the workforce of The Orange Door network. The Strengthening Cultural Safety in The Orange Door network project aims to support the delivery of a culturally safe environment for Aboriginal people seeking a service and the Aboriginal workforce through sustainable and locally driven implementation.

This project responds to the Victorian Auditor-General’s Office report on Managing Support and Safety Hubs released in May 2020, which recommended that FSV work with local ACCOs and community representatives to roll out mandatory cultural safety training specific to the functions and operations of The Orange Door network.

As at June 2021, the following activities had commenced:

- FSV had engaged the Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency (VACCA) to lead the development of a cultural safety training package that is tailored to the functions of The Orange Door networks.

- Work was underway to engage Cultural Safety Project Leads for each area in The Orange Door network. These roles will help build an understanding across all The Orange Door staff and governance groups. They will be responsible for:

- the delivery of cultural safety training that is locally tailored

- implementing a consistent cultural safety assessment and action planning process that is endorsed by the local Aboriginal Advisory Groups

- embedding a continuous quality improvement cycle through action plan reviews that reflect on a continuum of learning process at an individual and organisational level.

- Engagement had occurred with all Hub Leadership Groups to ensure their obligations and commitment to supporting continuous improvement in cultural safety.

In 2021-22, nearly 11,000 people provided with a response from The Orange Door network identified as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander. Of these, 50.1% were adults and 49.9% were children or young people (including unborn children). This represented 8.3% of all people who were provided with a response from The Orange Door network in 2021-22, falling marginally from 8.5% in 2020-21.

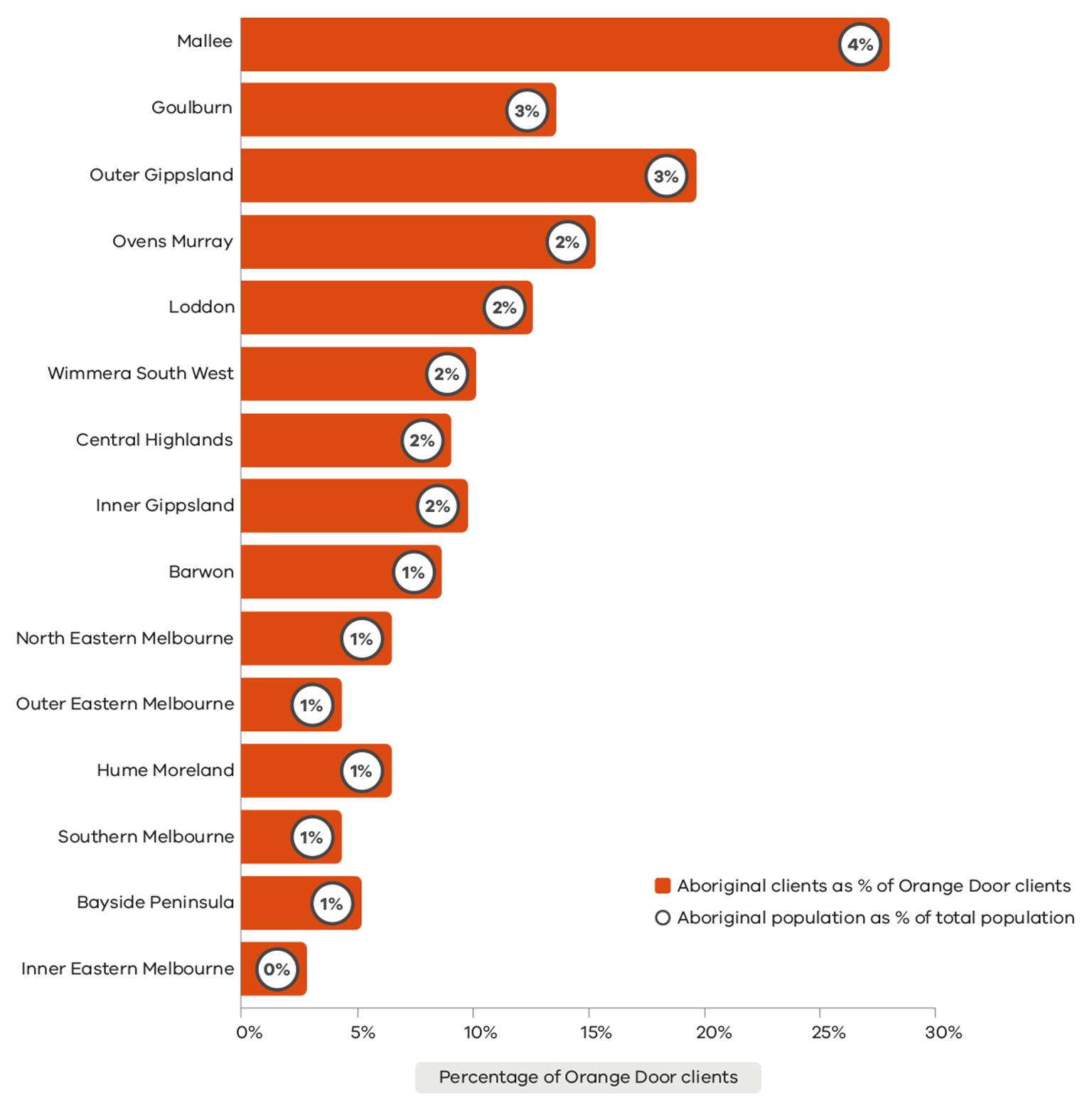

This varied across The Orange Door areas in 2021-22, with a greater proportion of services delivered to Aboriginal clients in regional areas, ranging from 27.7% in Mallee to 2.5% in Inner Eastern Melbourne (Figure 10). This can be partly explained by variation in population size, with Aboriginal people representing approximately 4.1% of the broader population in the Mallee area but 0.3% of the broader population in the Inner Eastern Melbourne.

Aboriginal people remain significantly impacted and over-represented among The Orange Door network’s client base, highlighting the strong need for culturally safe and appropriate responses tailored for this community. To expand accessibility for Aboriginal people, at the time of writing Aboriginal Access Points were planned to be established in Bayside Peninsula and Barwon to provide an additional option for Aboriginal people to access services and support.

Additionally, an Aboriginal Inclusion Action Plan for The Orange Door network has been developed in consultation with the Dhelk Dja Koori Caucus, Priority Sub-Working Groups and Aboriginal Advisory Groups. The Aboriginal Inclusion Action Plan was finalised and endorsed by the Dhelk Dja Partnership Forum in August 2021. The Aboriginal Inclusion Action Plan is aligned to Dhelk Dja Agreement: Safe Our Way – Strong Culture, Strong Peoples and Strong Families and underpinned by the principles in the Ngarneit Birrang Holistic Healing Framework.[15]

Dhelk Dja is the key Aboriginal-led Victorian agreement that commits the signatories to work together and be accountable for ensuring that Aboriginal people, families, and communities are stronger, safer, thriving and living free from family violence. It articulates the long-term partnership and directions required at a state-wide, regional, and local level to ensure that Aboriginal people, families, and communities are violence free and that services are built upon the foundation of Aboriginal self-determination.

The Dhelk Dja Three Year Action Plan articulates the critical actions and supporting activities required to progress the Dhelk Dja Agreement’s five strategic priorities. Each of these priorities recognise the need to invest in Aboriginal culture, leadership and decision making as the key to ending family violence in Victorian Aboriginal communities.

Djalu and Chloe: addressing Aboriginal child well-being alongside family violence[16]

Djalu is a 10-year old Aboriginal child, whose Aboriginal father passed away when Djalu was much younger. Djalu has limited connection to his culture and community and Djalu’s mother Chloe does not identify as Aboriginal. The school psychologist referred Djalu to The Orange Door network as he was presenting as highly anxious and disengaged from school.

The Aboriginal responses team engaged with Djalu and Chloe. Chloe disclosed that she had ended a relationship with a non-Aboriginal man called Craig who continued to use significant violence and abuse, including stalking and monitoring her. Chloe both disclosed a distrust of social services and her diagnosis of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, as well as Borderline Personality Disorder.

When the Aboriginal responses team engaged with Djalu, he was protective of Chloe and fearful of being apart, both because of the violence Chloe was experiencing, as well as her mental health needs.

The Aboriginal responses team arranged a visit at the home, which reduced Chloe’s sense of distrust. Djalu and Chloe were provided brokerage funding to install security systems, as well as duress watch for Djalu so that he would feel safe when not with Chloe.

With support from the Aboriginal responses team, Chloe made statements to Victoria Police. The Family Violence Investigation Unit supported Djalu and Chloe by establishing a family violence intervention order so that Craig could no longer contact either of them. Due to the risk of family violence, Child Protection were also involved. The Aboriginal responses team worked closely with Child Protection so that Djalu remained in Chloe’s care but with additional supports.

The Aboriginal responses team worked closely with Djalu and Chloe to improve their trust in services. Djalu was referred to a therapeutic service delivered by a local Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisation who was able to strengthen his connection to his culture and community. Chloe was referred to family violence case management to provide longer-term support. The Aboriginal responses team also worked closely with Djalu’s school and he is now well engaged in his education.

Notes

[11] The Orange Door Inclusion Action Plan is a two-year plan to embed inclusion, access, and equity in the services and policies of The Orange Door network. Developed in 2019-20 with partner agencies and released in 2021, it sets out how The Orange Door network will ensure services are accessible for all clients and offer supports tailored to individual needs and experiences. More information about the statement can be found at Everybody Matters: Inclusion and Equity Statement webpage, State Government of Victoria, accessed 13 October 2022.

[12] In instances where families are referred to The Orange Door network, practitioners consider the needs of each individual family member separately. Accordingly, the number of individuals The Orange Door network works with is greater than the number of referrals received.

[13] Names and identifying features of the people involved in this case study have been changed.

[14] Australian Bureau of Statistics 2021, Indigenous Status (INGP) by Victorian Local Government AREA, [Census TableBuilder], accessed 13 October 2022.

[15] Dhelk Dja Agreement: Safe Our Way – Strong Culture, Strong Peoples and Strong Families the Aboriginal 10-year Family Violence Agreement 2018-2028 webpage and Nargneit Birrang - Aboriginal holistic healing framework for family violence webpage, State Government of Victoria, accessed 13 October 2022.

[16] The following case study contains descriptions of family violence including coercive and controlling behaviours. Names and identifying features of the people involved in this case study have been changed. The case study also includes a description of an Aboriginal person who has passed away and their name has not been included in the case study.

Updated