- Published by:

- Family Safety Victoria

- Date:

- 7 Feb 2021

Message from the responsible Minister

Message from the responsible Minister

The implementation of the Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management Framework (MARAM Framework) is a Whole of Victorian Government reform that is committed to keeping victim survivors safe and perpetrators in view and accountable.

This is the second annual report into the operation of the MARAM Framework. This report covers the period from July 2019 to June 2020.

All Ministers with framework organisations within their portfolios have reported to me on the work being undertaken to align to the MARAM Framework. This report is consolidated from my portfolio report and the reports provided by:[1]

- The Hon. Jill Hennessy MLA, (previous) Attorney-General

- The Hon. Jenny Mikakos MLC, (previous) Minister for Health

- The Hon. Lisa Neville MLA, Minister for Police and Emergency Services

- The Hon. Luke Donnellan MLA, Minister for Child Protection

- The Hon. Martin Foley MLA, (previous) Minister for Mental Health

- The Hon. Melissa Horne MLA, Minister for Consumer Affairs, Gaming and Liquor Regulation

- The Hon. Natalie Hutchins MLA, Minister for Crime Prevention, Minister for Corrections, Minister for Youth Justice, Minister for Victim Support

- The Hon. Richard Wynne MLA, Minister for Housing

This has been a challenging year that has seen the devastating bushfires across regional Victoria and the ongoing impact of the coronavirus (referred to as COVID-19) pandemic across Australia and the world. We know that the risk of family violence not only remains present during such events but increases in incidence and severity.

The MARAM Framework and the work across departments in preparing their organisations to embed family violence response into their systems has placed workforces in a stronger position to respond to this risk during these unprecedented times.

Essential community services from the police to the Courts, Housing, Child Protection, Alcohol and other Drugs have all ensured family violence response formed a part of their business continuity planning when implementing their COVID-safe delivery plans. This is, of itself, testament to the impact of the Royal Commission into Family Violence (the Royal Commission) reforms in making family violence response a collective system responsibility and a lasting cultural change.

I particularly wish to acknowledge the work of specialist family violence practitioners and sexual assault workers who have been crucial partners in supporting the response to family violence during these difficult times. As well as pivoting their own practice to address the complications of responding to family violence during a global pandemic, they have offered unwavering support to other services that have seen an increase in family violence identification and risk. Aboriginal Community-Controlled Organisations (ACCOs) have continued to provide amazing support through their connection to community and people. Victoria’s peak bodies have collaborated across sectors and with government to support their workforces. I thank them all for their continued work and dedication.

The MARAM and Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme (FVISS) reforms continue to be centrally led by Family Safety Victoria (FSV), with extensive cross-government collaboration with the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), the Department of Justice and Community Safety (DJCS), Victoria Police, the Magistrates’ Courts and the Children’s Courts (the courts), and the Department of Education and Training (DET). DET are the lead department on the related Child Information Sharing Scheme (CISS) reforms. This report outlines just some of the work departments, agencies, sector peaks and framework organisations have delivered over the course of 2019–20. Although only in year two of the reform, this report provides an early indication of the impact of change through independent evaluations and data collection.

This report also notes some of the challenges that are experienced, as may be expected in the early years of rolling out such an extensive reaching reform as MARAM. With 37,500 workers from Phase 1 organisations requiring training across the three reforms of MARAM, FVISS and CISS, and a need to tailor the centrally produced resources to multiple workforces, demand has been high, and it will take time to meet this need. This is being addressed through increasing use of online training and eLearn modules which will benefit the 370,000 workers due to be prescribed in Phase 2. There are related initiatives, such as the Aboriginal Workforce Development Initiative, which aims to increase trainer capacity to meet the needs of the Aboriginal workforce and those serving the Aboriginal communities. We will continue to work collaboratively across government to progress all related actions which will help make training and resources available to all.

Our next major step is preparing workforces for Phase 2 of the MARAM and information sharing reforms, set to commence in April 2021.[2] Government will use knowledge gained in the early evaluations to inform our next steps. This includes a renewed focus on change management activities across government departments and the sector, continued capability uplift across organisations, consistent guidance on the practical application of the reforms, and increased accountability and governance.

Implementation of MARAM is also captured in Building from strength: 10-year Industry Plan for family violence prevention and response (the Industry Plan) and the first three-year plan to progress this work in Strengthening the foundations: first rolling action plan 2019–22. This Whole of Government strategy, supported by departmental workforce and industry planning, focuses on the uplift of workforces spanning the specialist family violence sector, community services, health, justice and education and training to create a flexible and dynamic workforce to prevent and respond to family violence. This includes the development of family violence prevention and response knowledge and skills across all workforces, in line with the best practice approaches established through MARAM.

As we progress this important work, I thank all those across government and the services sector who have helped to improve the way we respond to family violence, and ensure that victim survivors get the support they need to move on with their lives.

Hon Gabrielle Williams MP

Minister for Prevention of Family Violence

Minister for Women

Minister for Aboriginal Affairs

[1] Ministers listed were the portfolio ministers for the reporting period.

[2] Subject to final Ministerial approval at the time of report preparation.

Portfolios within this report

Portfolios within this report

This table sets out the departments, Ministers, portfolios and program areas that are referenced in this report. See Appendix 1 for a more detailed description of each program area’s work profile.

|

The Hon. Gabrielle Williams, MP |

|

|

|

The Hon. Jenny Mikakos MP |

|

|

|

The Hon. Jill Hennessy MP |

|

|

|

The Hon. Lisa Neville MP |

|

|

|

The Hon. Luke Donnellan, MP |

|

|

|

The Hon. Martin Foley, MP |

|

|

|

The Hon. Melissa Horne MP |

|

|

|

The Hon. Natalie Hutchins MP |

|

|

|

The Hon. Richard Wynne, MP |

|

|

A note on language and terminology

A note on language and terminology

The word family has many different meanings. This report uses the definition from the Family Violence Protection Act 2008 (FVPA), which encompasses the variety of relationships and structures that can make up a family unit and the range of ways family violence can be experienced, including through family-like or carer relationships, including non-institutional paid carer environments.

The term family violence reflects the FVPA definition and includes the wider understanding of the term across all communities, including those identifying as Aboriginal.

Family violence is deeply gendered – overwhelmingly, most perpetrators are men and most victim survivors are women and children. It is acknowledged that broader conceptions of gender-drivers apply to individuals’ identities, experiences and manifestations of family violence. Therefore, this document does not use gendered language to describe every form of family violence.

In line with the Royal Commission and FVISS Guidelines, this document refers to victim survivors and perpetrators. The term victim survivor includes adults and children. We recognise that Aboriginal people and communities may prefer to use the terms ‘people who use violence’ and ‘people who experience violence’.

Throughout this document, the term Aboriginal is used to refer to both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

For adolescents, we use the term ‘adolescent who uses family violence’. This reflects that this is a form of family violence requiring distinct responses, given the age of the young person and their concurrent safety and developmental needs, as well as common co-occurrence of past or current experience of family violence by the adolescent from other family members

An older person who is experiencing family violence is often described as experiencing ‘elder abuse’.

Intersectionality describes how systems and structures interact on multiple levels to oppress, create barriers and overlapping forms of discrimination, stigma and power imbalances based on characteristics such as Aboriginality, gender, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, ethnicity, colour, nationality, refugee or asylum seeker background, migration or visa status, language, religion, ability, age, mental health, socioeconomic status, housing status, geographic location, medical record or criminal record. This compounds the risk of experiencing family violence and creates additional barriers for a person to access the help they need.

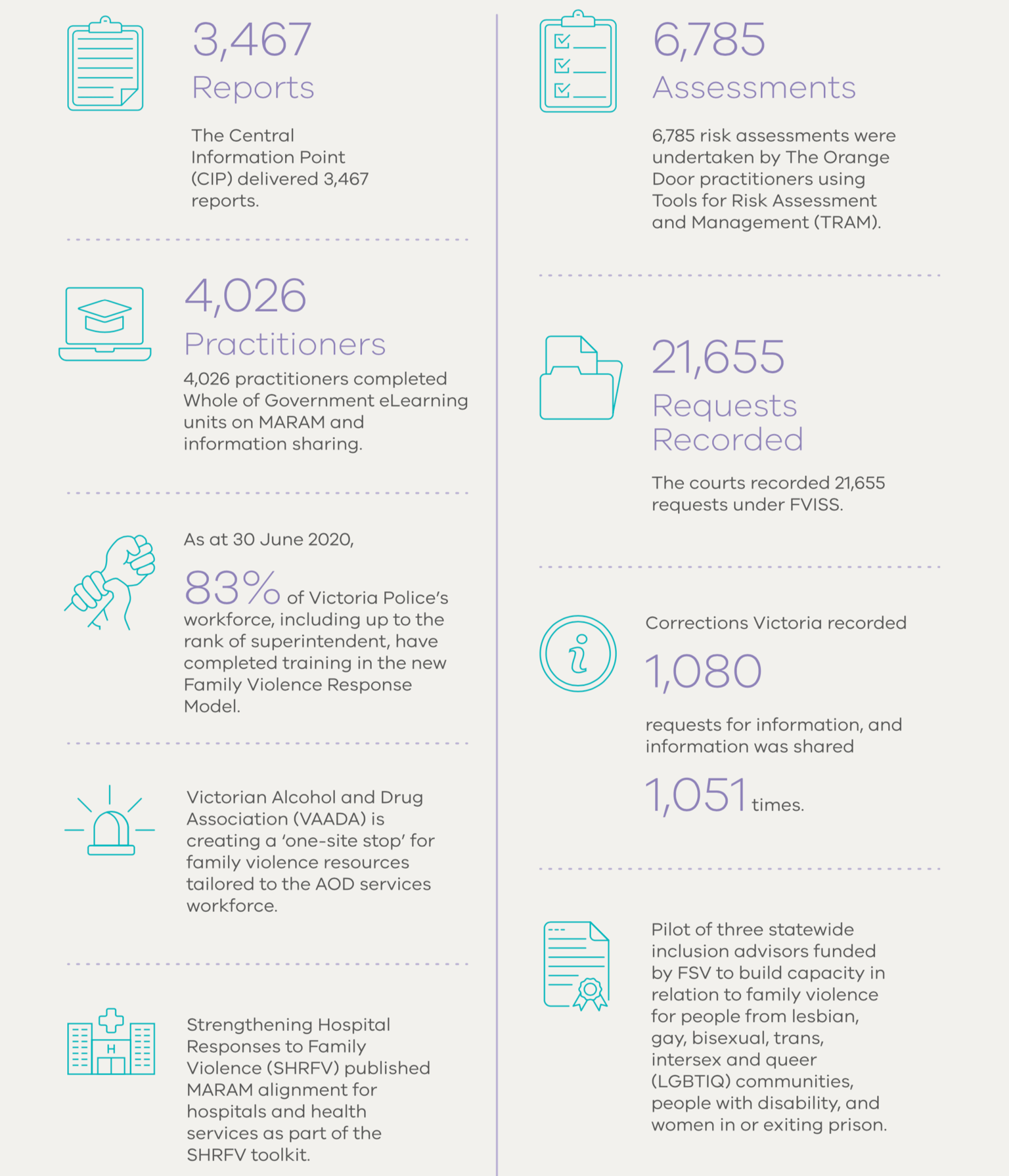

Whole of Government snapshot 2019–20

MARAM and information sharing — achievements since Royal Commission (2016)

MARAM and information sharing – achievements since Royal Commission (2016)

SYSTEM |

|

|

We have developed new risk assessment and management principles and system architecture |

The family violence Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management Framework (MARAM) was developed. Amendment of the Family Violence Protection Act 2008 has prescribed organisations to MARAM and the Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme (FVISS). New resources, tools and practice guidance have been developed for organisations to help them embed MARAM in their operations. |

WORKFORCE |

|

|

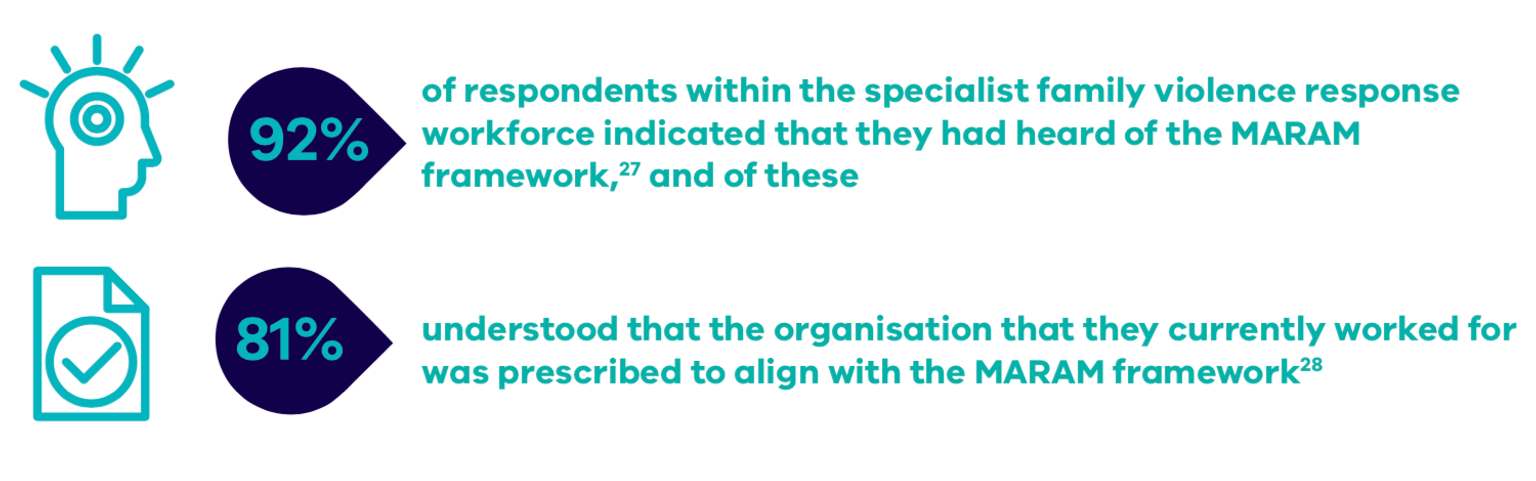

We are expanding the workforces covered by MARAM and information sharing and uplifting their professional competency |

Approximately 37,500 professionals across 850 organisations and services were prescribed to MARAM, FVISS and the Child Information Sharing Scheme (CISS) in 2018 with a further estimated 370,000 professionals across 5850 organisations and services to be prescribed in 2021. 18,671 workers have been trained in MARAM, FVISS or CISS across all platforms (as at June 2020). An accredited Vocational Education and Training (VET) unit of competency in identifying and responding to family violence was developed in 2020, with further work under the Industry Plan completed or in progress to uplift workforce capability and competency. |

EMBEDDING |

|

|

We are embedding MARAM and information sharing across the system |

Change management positions have been funded in the Department of Health and Human Services, Department of Justice and Community Services, Department of Education and Court Services Victoria to support the embedding of MARAM in relevant sectors. A range of peak bodies and other entities have received funding to support this through the Sector Grants program. Victoria Police L17 family violence incident forms have been updated with additional questions relating to risk for children and additional recognised forms of family violence. MARAM screening and risk assessment questions have been embedded into hospitals and health services data systems, (noting hospitals are yet to be formally prescribed) as well as on the Specialist Homelessness Information Platform (SHIP) The Central Information Point (CIP) brings together information on perpetrators from Victoria Police, Courts, Corrections Victoria and Child Protection. This information is provided in a single report to professionals, supporting informed risk assessment and management. |

REVIEW |

|

|

We are evaluating as we go and building an evidence base |

The first MARAM annual report 2018–19 on implementation of the Framework was tabled in Parliament by the Minister for Prevention of Family Violence on 20 February 2020. An early MARAM process evaluation and the legislated two-year review of the FVISS were completed in June 2020. The review of the FVISS was tabled in Parliament by the Minister for Prevention of Family Violence on 18 August 2020 |

Impact of COVID-19

Impact of COVID-19

At the time of preparation of this report, metropolitan Melbourne has been subject to varying degrees of restrictions since March 2020. Prior to that, regional Victoria was seriously affected by the bushfires. This has had a significant impact on MARAM implementation, as it has on all parts of the service system. The COVID-19 pandemic naturally led to an urgent re-prioritisation of planned activities.

We know from national and international evidence that family violence risk and incidences of family violence increases during disasters. International and local experience demonstrates that measures introduced to limit the spread of coronavirus increase the risks perpetrators pose to victim survivors.[3] Monash University surveyed family violence practitioners across Victoria in April and May 2020. Almost 60 per cent of respondents said the COVID-19 pandemic had increased the frequency of violence against women; 50 per cent said the severity of violence had increased, and 42 per cent of respondents noted an increase in first-time family violence reporting.[4]

Evidence also suggests that recessions and unemployment, which have arisen from the pandemic, can have negative impacts on mental health, relationships and parenting, which are recognised risk factors for family violence.[5] Emerging research shows that the COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately impacted women’s employment.

Early evidence related to job loss and the economic impacts of COVID-19 suggest that women are facing increased economic insecurity. Financial hardship coupled with more time spent at home due to social distancing and isolation measures is placing individuals at risk of domestic violence.[6]

The potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic directions and associated restrictions on the response to family violence has not been underestimated by the Victorian Government. Departments have taken significant steps to pivot their services to remote models rather than face to face, so as to effectively respond to the increased family violence risk while maintaining MARAM alignment.

The MARAM Framework enables a foundation for a shared understanding of risk and a consistent approach to response across the service sector. FSV produced COVID-19 resources that retain MARAM at their core, which departments used in their own business continuity plans. FSV has also supported communities of practice for non-specialist workforces in their response to increased identification and response to family violence through online engagement.

Due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, some planned MARAM alignment projects were paused to prioritise the production of resources for frontline workers specifically focused on the challenge of increased family violence risk during the pandemic. There has also been a concerted effort to move training online. The increased burden on framework organisations may have impacted their capacity to report and provide data in time for this report.

One impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been a delay to commencement of Phase 2 organisations from September 2020 to April 2021.[7] This purposeful delay recognises the critical role educators and universal health services play in Victoria throughout the pandemic, as well as points of intervention for family violence identification.

In the context of this report, a further impact of the pandemic is a delay to the implementation and use of the Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E) Framework which is linked to the Family Violence Outcomes Framework. The M&E Framework has been provided to all departments, and it is intended to form a part of alignment activities for departments going forward. Part of the M&E Framework is to gather data regularly through use of a MARAM Framework annual survey. Evaluation against outcomes in this year’s consolidated report will be limited in terms of data references to the findings of evaluations as a result.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on all aspects of every workforce cannot be underestimated. Research undertaken by Monash University has shown that the pandemic has in particular caused specialist family violence practitioners to feel a heightened sense of isolation and loneliness working from home and missing the incidental support and debriefing provided by colleagues. It has also shown the blurring of boundaries between work and home life, leading to family violence work invading practitioners’ ‘safe spaces’. While the Monash report did show the COVID-19 pandemic had some upside, particularly in service innovation, such as practitioner-led development of an alert system for women to signal when they need support, further work is needed to progress health, safety and wellbeing supports.[8]

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted opportunities for further engagement with victim survivors and responding to family violence through non-prescribed organisations, such as:

- supporting and raising the capability of contact tracing and testing workers to provide support to people who may be experiencing or using family violence

- working with non-MARAM prescribed essential services such as supermarkets and pharmacies that are accessible under stage 3 and stage 4 restrictions and have the potential to promote family violence support numbers and potentially be a safe place to call a specialist family violence service.

[3] The Crime Statistics Agency records that the monthly number of family violence incidents was higher in every month during 2020 than 2019. In June 2020, the number of incidents was 15 per cent higher than in June 2019 https://www.crimestatistics.vic.gov.au/media-centre/news/police-recorded-crime-trends-in-victoria-during-the-covid-19-pandemic.

[4] Pfitzner N, Fitz-Gibbon K and True J 2020, Responding to the ‘shadow pandemic’: practitioner views on the nature of and responses to violence against women in Victoria, Australia during the COVID-19 restrictions, Monash Gender and Family Violence Prevention Centre, Monash University, Victoria, Australia, https://research.monash.edu/en/publications/responding-to-the-shadow-pandemic-practitioner-views-on-the-natur (accessed 12 June 2020).

[5] Demand for social services such as mental health and family relationship services, financial and material support, housing, and employment/training services will increase with increased unemployment and slow wage growth (Access Economics, 2008). Recession is possibly associated with a higher prevalence of mental health problems, including common mental disorders, substance disorders, and ultimately suicidal behaviour (Frasquilho et al. 2016). Unemployment has negative economic, social, physical health and mental health impacts, which can flow on to other family members, including children. Most of these are reversible if the unemployed person is re-employed relatively quickly (Gray et al. 2009). Relationship breakdown increased slightly in recessions (Charles and Stephens, 2004). The longer the duration of unemployment, the greater the risk of detrimental impacts on relationships (Kraft, 2001). Increasing unemployment may correlate to increased risk for children as the psychological impacts of unemployment on parents can adversely impact upon parenting and, consequently, children’s wellbeing (Gray et al. 2009).

[6] Workplace Gender Equality Agency 2020, Gendered impact of COVID-19, Australian Government, www.wgea.gov.au (accessed 8 October 2020).

[7] Subject to final Ministerial approval at the time of report preparation.

[8] Pfitzner N et al. 2020, op. cit.

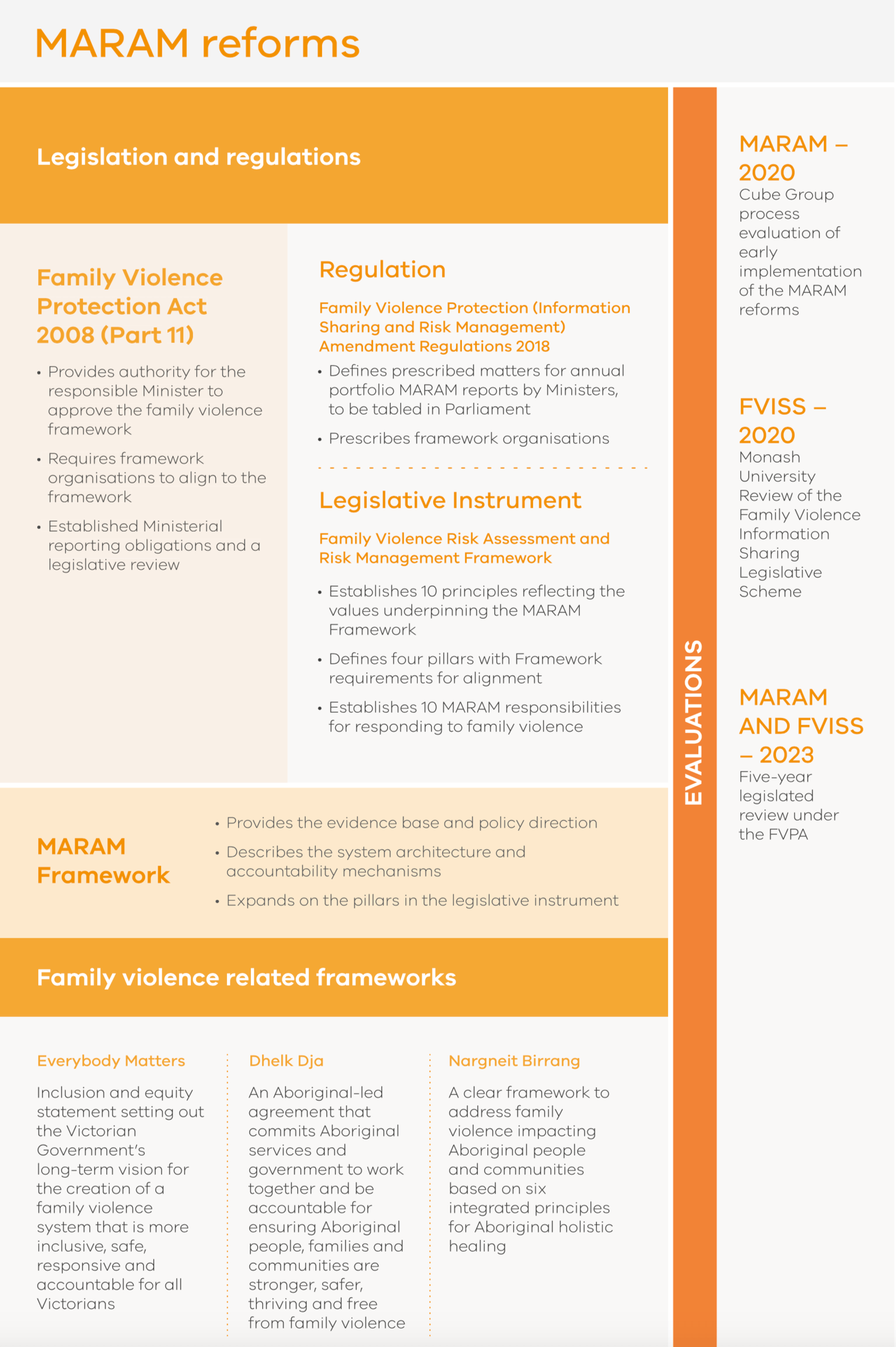

Our commitment — Victoria's family violence legislative and policy frameworks

Our commitment — Victoria's family violence legislative and policy frameworks

Victoria’s commitments arising out of the Royal Commission commenced with amendments to the FVPA, and the successful translation into regulations and policy resulting in the MARAM Framework.

The work has continued to underpin the MARAM Framework through supportive policies, plans and strategies.

Set out below is an overview of the legislation, policy and frameworks that support Victoria’s response to family violence.

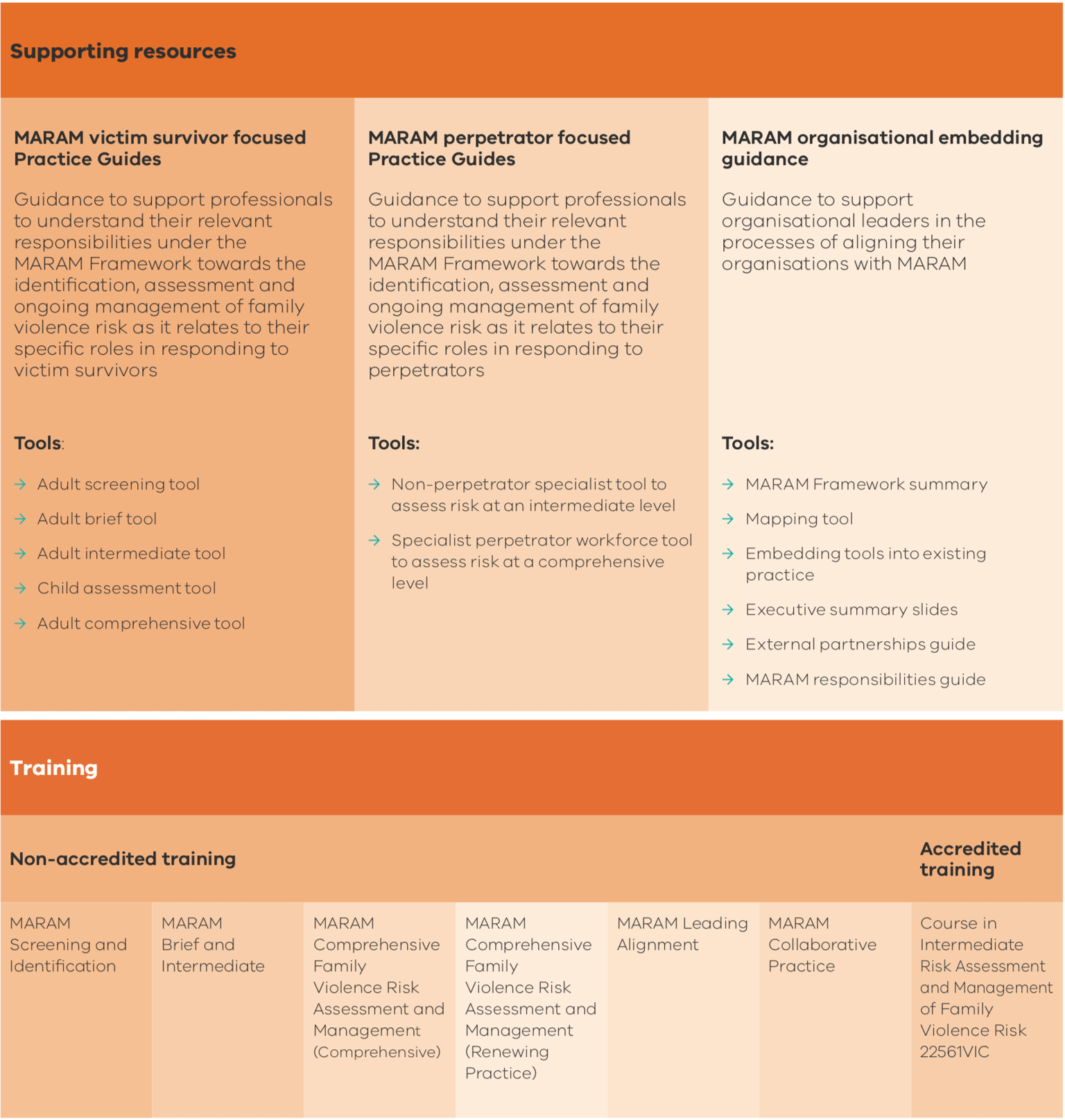

Whole of Government training and resources

Whole of Government training and resources

FSV continues to develop resources and deliver and develop training with government partners and stakeholder engagement.

Set out below is an overview of the resources and training developed (or in development) since the outset of the reforms.

Structure of this report

Structure of this report

The MARAM Framework is intended to create a model of response that can be used by all services that connect with individuals and families who may be experiencing family violence.

It covers all aspects of service delivery from early identification, screening, risk assessment and management, to safety planning, collaborative practice, stabilisation and recovery.

The objectives of the MARAM Framework are to:

- increase the safety of people experiencing family violence

- ensure the broad range of experiences across the spectrum of seriousness and presentations of risk are represented in family violence response, including for Aboriginal and diverse communities, children, young people and older people, across identities, and family and relationships types

- keep perpetrators in view and hold them accountable for their actions

- provide guidance on how to align to the MARAM Framework to ensure consistent service delivery.

To enable legislative reform to be implemented in a meaningful way across services and organisations, four strategic priority areas were identified and endorsed in the Whole of Government change management strategy in December 2019:

- Provide clear and consistent leadership through departments and sector peaks to support organisations and workforces in alignment.

- Facilitate consistent and collaborative practice through the implementation of key policies, procedures, practice guidance and tools across workforces including information sharing.

- Build workforce and staff capability through centralised Whole of Government training products, and adapted resources and training for workforces, as well as other capability raising measures.

- Reinforce good practice and commitment to continuous improvement through sharing key lessons, refining practice and addressing barriers as they emerge.

This report is structured around the four strategic priorities of the change management strategy. Each chapter starts with highlights from across the whole of government, continues with some detailed examples from across portfolios and concludes with an assessment of how the work undertaken is meeting the objectives of the MARAM Framework.

As alignment with MARAM increases, future reports will be able to chart the progress against the MARAM objectives and the change management strategy strategic priorities.

This report does not capture the full range of activities undertaken by departments and portfolio agencies, as the purpose is to provide a snapshot of achievements in MARAM alignment from 1 July 2019 to 30 June 2020 across the Victorian Government.

Case studies to demonstrate the impact of initiatives have also been included with names and some details changed to provide anonymity.

1. Provide clear and consistent leadership

1. Provide clear and consistent leadership

Clear leadership is integral to the implementation of information sharing and MARAM on several levels.

FSV leads the reforms by ensuring departments, prescribed agencies and sector peaks receive consistent and accurate messaging. Departments[9] and sector peaks lead by using these key messages, tailoring communications for their workforces, and using tailored guidance to implement the reforms. Departments and sector peaks have played a critical role within their areas of responsibility in ensuring sector readiness and the long-term cultural change necessary to implement and embed the reforms.

Key highlights

Government-led highlights:

- FSV practice notes to support specialists and universal services with pandemic relevant risk assessment and management resources

- The courts developed MARAM-aligned tools and practice guidance for risk assessments and safety planning for family violence practitioners while working remotely during the coronavirus pandemic

- Online training across FSV, DHHS and DJCS to support prescribed sectors

Sector-led highlights:

- Centres Against Sexual Assault (CASA) Forum established working groups to support alignment and implementation

- VAADA held several workshops and forums across the state to support the sector to understand their information sharing obligations and MARAM responsibilities

- CAV have built the capability of the practitioners in Financial Counselling Program (FCP) and Tenancy Assistance and Advocacy Program (TAAP) through tailored MARAM tools, guides, training and regular communications

Sector grants

For the third consecutive year, FSV funded $1.5 million worth of grants directly to the sector. These funds were distributed by FSV, DHHS and DJCS to 16 peak or other representative bodies from Phase 1 workforces across the service system to provide direct implementation support. This included five ACCOs.

Some highlights from the sector grants work in 2019–20 include:

- development of cross-sector understanding and relationships through the MARAM and Information Sharing Sector Capacity Building Working Group and Aboriginal Working Group

- production and sharing of culturally appropriate case studies, information sheets and practice guides tailored to workforces and reflecting people’s experience of family violence

- webinar produced collaboratively by CASA Forum, Domestic Violence Victoria (DV Vic) and No to Violence (NTV): ‘Responding to serious risk and sexual assault’

- Collaboration across a variety of sectors including Aboriginal services, Disability Services, and Multicultural services to better support the intersectionality aspect of MARAM alignment

- The five funded ACCOs established a bi-monthly community of practice to develop responses to the MARAM reforms.

To ensure consistency and continuity of leadership, all 2019–20 sector grant recipients were invited to submit funding and project proposals for 2020–21.

Sector grants in use

The ACCOs that make up the Sector Capacity Building Aboriginal Working Group hold a bimonthly community of practice (CoP).

The CoP aims to facilitate a culturally inclusive, trauma-informed and safe meeting space where conversations and collaborative practice continue to thrive. It has become a valuable, independent forum to work through complex and crucial issues and has strengthened our networks and our working relationships.

The MARAM ACCO CoP is a strong, bonded group comprising Dardi Munwurro, Djirra, Elizabeth Morgan House, VACCA and VACSAL. While the CoP does not claim to represent or speak for the Victorian Aboriginal community, the underlying values and purpose of the group echo the founding principle of self-determination as outlined in Dhelk Dja: Safe our way (2018).

The CoP’s collective response aims to highlight the best approach, practice and advice so that a cultural perspective and framework is heard, understood and embedded within the family violence sector. The CoP uses its position and experience to provide collective advocacy for the Aboriginal community and to build capacity and capability.

A significant responsibility of the CoP is to provide culturally inclusive responses to requests from government. Through a united voice in response to MARAM alignment, the CoP provides a culturally framed focus on specific issues that impact on the Aboriginal community.

The CoP has had many achievements so far, including:

- advocating for more Aboriginal voices in training

- highlighting the importance of cultural training

The CoP also:

- provides leadership in driving agenda and discussion topics in ACCO and mainstream working groups

- participates in evaluations and provides a collective response

- provides reviews of crucial documents including the MARAM Practice Guidelines and Family Violence modules

- advocates for additional collective funding for review of documents.

The CoP continues to provide advice about how culturally safe approaches can be incorporated into the MARAM materials for ACCOs and mainstream organisations. The next step is to share and extend the learnings to the wider sector, by providing guidance with a clear cultural lens.

Specialist Family Violence Advisors (SFVA)

Through Industry Plan funds, DHHS has funded 44 SFVA in Mental Health and AOD services, who in turn provide information to DHHS and FSV Centre for Workforce Excellence on the actions taken under the initiative. This ensures specialist family violence advice is available to AOD and Mental Health practitioners, whom the Royal Commission identified as playing a critical role in identifying and responding to family violence.

The SFVA roles help support MARAM alignment by supporting practitioners in identifying, assessing and managing family violence risk and promoting collaborative practice with other agencies.

Victoria Police

Information held by Victoria Police is crucial to keeping perpetrators in view and accountable for their actions and behaviours. Victoria Police have promoted the importance of information sharing by engaging closely with other Information Sharing Entities (ISEs) to improve the processes for requesting information. As a result, the request form (and associated processes) were updated to be more intuitive for ISE, ensuring the correct information was requested and released in accordance with Ministerial guidelines to avoid delays.

Victoria Police continues to participate in Whole of Government governance groups and engages with Phase 2 framework organisations for preparation towards additional information sharing requests.

The Courts

The Magistrates’ Court of Victoria (MCV) and the Children’s Court of Victoria (CCV) (collectively known as ‘the courts’) and the funded agency Court Network established a shared project to align court operations with the MARAM Framework. The project’s implementation roadmap outlines a three-year plan to align the courts with the MARAM framework, with key milestones for each year. In addition, the courts have mapped responsibilities for initial family violence identification and screening, and risk assessment and management.

The roadmap helps support MARAM alignment throughout every level of the courts process.

In 2020–21, the courts will develop an overarching MARAM policy and embed the framework into existing operating guidelines and practice models, such as the specialist family violence courts (SFVC) model, bench clerk manuals and practitioners’ guidelines. In September 2019 the Shepperton SFVC commenced, the Ballarat SFVC commenced operation in November 2019 and the Moorabbin SFVC commenced operation on 16 March 2020.

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, Court Network launched a telephone support model in May 2020. The phone model is staffed by volunteers who support court users to navigate the justice system. The practice model includes universal screening in line with base level MARAM screening and identification of family violence.

Court Network volunteers supported 32,470 court users with family violence related matters in 2019–2020.

DHHS

MARAM planning and implementation is underway for Child Protection, Housing, secure welfare services and Hurstbridge Farm. DHHS have convened a MARAM Implementation Steering Group to oversee the implementation activity across these prescribed workforces and provided leadership for the reforms.

Victoria’s Director of Housing manages over 62,000 properties, providing safe, long-term housing to people on low incomes. Priority is given to those most in need, including people who have recently experienced family violence.

A new housing operating model will be introduced during the 2020–21 financial year; Housing Service Officer (HSO) roles will be realigned in their relationship to Victorian Public Service (VPS) roles, and over 130 amendments to the Residential Tenancies Act 1997 are being progressively implemented, including specific provisions concerning family violence that were established in mid-2020.

FSV – The Orange Door

The Orange Door is coordinated by FSV.

The Orange Door model brings together specialist family violence services, children and family services, Aboriginal services and perpetrator services to deliver integrated assessment and access to support. This incorporates tailored support for women and children experiencing family violence, holistic support for Aboriginal families in local communities, help with the care and wellbeing of children, and work with perpetrators to manage risk and change behaviours.

A recent report by the Victorian Auditor-General’s Office (VAGO) assessed whether The Orange Door sites are providing effective and efficient service coordination for women and families and in particular whether DHHS and FSV:

- designed and planned the hubs effectively

- effectively support and oversee the operation of the five open hubs

- have reliable performance measurement and continuous improvement processes.

The VAGO report concluded that the hubs are not yet realising their full potential to improve the lives of people affected by family violence. The report recognised that FSV is working to improve the implementation of future sites and continues to build on the learnings of implementation to inform the future roll out of The Orange Door Network. DHHS and FSV have accepted all nine recommendations of the VAGO Audit.

FSV will work with all partner agencies and key stakeholders to embed MARAM into existing and new The Orange Door sites. This will include supporting the workforce to utilise the MARAM tools in TRAM for their risk assessment and safety planning for adult and child victim survivors ensuring greater consistency of identification, risk assessment and management.

Family Violence Peak Bodies

Domestic Violence Victoria

DV Vic as the peak body for SFVS established and facilitated a community of practice (CoP) with a focus on applying the MARAM and Information Sharing Schemes in practice. The group provides opportunities to share experiences, discuss emerging issues and support consistent practice while driving change within organisations across the state.

The group is run online to support member service participation from regional and remote areas. However, this format has also allowed the CoP to continue and not be disrupted due to COVID-19 pandemic restrictions.

Fourteen CoP sessions have been delivered to SFVS Practice Leads. Topics have included:

- operationalising tools for risk assessment and management

- risk assessment and safety planning with victim survivors with a disability

- tilting to the perpetrator

- working collaboratively with perpetrator services

- risk and safety during COVID-19

- person-centred empowerment during COVID-19

- maintaining child-centred practice during COVID-19

- collaboration and advocacy during COVID-19

- perpetrator accountability during COVID-19.

The Practice Lead CoP has been successful in:

- promoting a model of best practice standards and work towards state-wide consistent, transparent and accountable practice

- providing a foundation to generate and manage a body of knowledge for ongoing reflection of practice and continuous improvement

- providing a consistent online platform to host resources to inform practice and strengthen program delivery

- providing opportunities for peer support and the exchange of ideas and information

- gathering and sharing evidence from practice to inform policy, advocacy and the broader reform agenda.

No to Violence

No to Violence (NTV) supported the Victorian men’s specialist family violence services in the implementation of the MARAM and Information Sharing (MARAMIS) reforms through a combination of targeted capacity building initiatives.

NTV developed a coaching model that involved reaching out to team leaders and coordinators within men’s specialist family violence services to determine their specific needs around support implementing MARAM and information sharing. If services were interested in engaging NTV to facilitate a workshop with leadership or practitioners, they completed a pre-workshop survey to determine the target areas of content. The Practice Development Officer then visited services onsite and facilitated a tailored workshop to support embedding the reforms in practice. The visits were also an opportunity to offer team leaders assistance with workforce mapping and implementation of alignment through the NTV resources ‘Workforce mapping tool’ and ‘Self-audit alignment tool’.

NTV then followed-up with established key contacts to provide resources and support in response to the workshop discussions, and any actions that came out of the completion of the mapping and alignment tools, such as reviewing implementation plans and providing guidance on training requirements.

Assessment of MARAM progress

Given the complexity of the MARAM reforms, which have required a Whole of Government change management approach, clear and consistent leadership is integral to delivering consistent service delivery. The coordination and oversight of the reforms involves many sectors and government portfolios and requires that government, peak and industry bodies and services work together.

Cube Group led the early evaluation of the MARAM reforms and produced a final report in June 2020. The report recognised many strengths in leadership towards achieving the reform outcomes including highly consultative governance forums and robust discussions of key policy issues. The decision to integrate governance for the MARAM, FVISS and CISS reforms was challenging, but it successfully allowed important overlapping issues to be managed. Where available, FSV’s active support has been positive.

All departments have experienced challenges primarily created by uncertainty. Short-term funding, the challenge of retaining staff with short-term contracts and competing priorities from other reform programs are key contributors to this context.[10] This has been further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The leadership actions taken to date have ensured that Phase 1 workforces have taken important steps towards building a shared understanding of family violence and identifying the way in which services can respond to family violence. A considerable amount of work remains to be done for Phase 1 workforces, including embedding a MARAM-aligned family violence response through tailored training, developing MARAM aligned resources and building collaborative practice (see chapters 2 and 3).

Departments and the workforces within their remit each have a unique context for implementation that naturally requires variation in implementation approaches.[11] It is important for central department specialist teams to work closely with business units to facilitate a nuanced approach to implementation activities that considers the varied roles of prescribed business units and the context in which they work.[12] FSV will continue to take a centralised lead role, supporting departments to achieve MARAM outcomes as outlined in their individual departmental and sector grant project alignment plans, and by providing oversight and change management advice.

The early evaluation of the MARAM reforms by the Cube Group recommended that departments remain best placed to lead change management for their own sectors, and that the plans for change management will need expanding considerably to achieve the MARAM outcomes and in the future through the development of a maturity model of alignment[13]. FSV has already taken such steps through the release of an organisational embedding guidance[14] that provides clear, published guidance MARAM alignment which will be foundational for a maturity model.

Funding for sector grants and for SFVA positions will assist in the connection between departmental change management plans and translation to practice support for the workforces.

[9] Noting DJCS includes Victoria Police and the Courts.

[10] Ibid., p. 62.

[11] Ibid., p. 14.

[12] Ibid., p. 62.

[13] Ibid., p. 90.

[14] See the ‘MARAM organisational embedding guide’ section in chapter 2.

2. Facilitate consistent and collaborative practice

2. Facilitate consistent and collaborative practice

FSV have a lead role in producing centralised resources. Organisations are guided by tailored resources developed by departments and sector peaks that support a change in practice.

Key highlights

Government-led highlights:

- The victim survivor focused Practice Guides and tools support professionals in their screening, identification, risk assessment and risk management practice, and were publicly released in July 2019.

- MARAM Practice Notes and factsheets to support targeted responses to family violence during the COVID-19 pandemic were released between March and June 2020.

- The organisational embedding guide (OEG) was released online in June 2020 to support organisations in their alignment to MARAM.

- The CIP delivered 3,467 reports.

Sector-led highlights:

- NTV provided individualised support for organisations in the alignment of their policies, processes and practice guidance.

- DV Vic redeveloped the Specialist Family Violence Services Code of Practice to align with the MARAM Framework.

- The Centre for Excellence in Child and Family Welfare (CECFW) developed a range of resources for Child and Family Services, including Child FIRST, and care services sectors, including a series of podcasts featuring interviews and Q&As with leaders in the field, as well as information sheets.

Portfolio examples – resources and tools for consistent practice

MARAM tools and Practice Guides

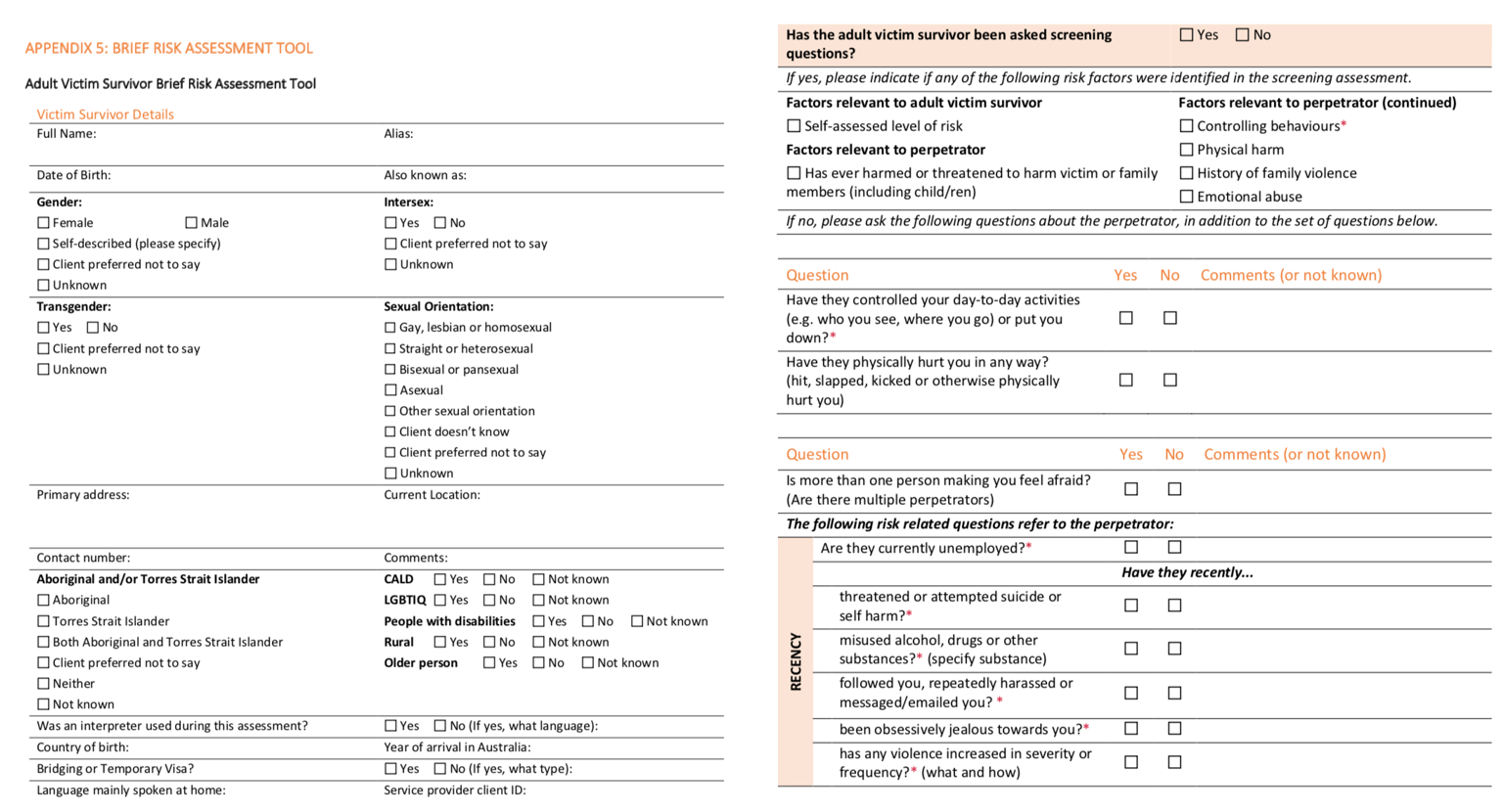

The victim survivor focused Practice Guides and tools, released in July 2019, support professionals in understanding their risk assessment and risk management practice under the MARAM Framework. There is a foundational knowledge guide, and individual Practice Guides for each MARAM responsibility.

The resources include risk assessment tools and safety plan templates for adults, and children and young people which can be tailored and/or embedded into existing tools by services.

Work is now being undertaken to develop perpetrator focused Practice Guides and tools. These will replicate the same structure as the victim survivor focused Practice Guides, supporting practice across the 10 MARAM responsibilities.

The perpetrator focused program of work includes:

- non-specialist perpetrator workforce guides and tools (such as Mental Health, AOD, Housing/Homelessness and Child Protection) to assess risk at an intermediate level

- specialist perpetrator workforce guides and tools (such as men’s behaviour change practitioners) to assess risk at a comprehensive level.

FSV is collaborating with NTV and other experts on the Practice Guide development, and with Curtin University on the developments of the tools. It is anticipated that perpetrator focused Practice Guides and tools (specialist and non-specialist will all be released by early 2021.

In conjunction with the CECFW, FSV will continue to build the evidence to respond earlier to adolescents who use family violence. FSV is seeking to strengthen the capacity of workforces to respond to adolescents which will include embedding further guidance on adolescents who use family violence into the next Phase of MARAM Practice Guides.

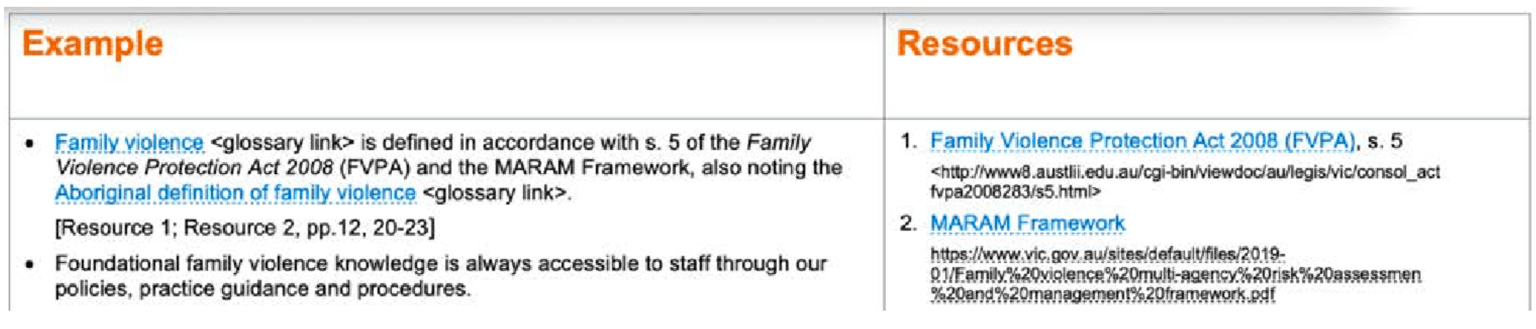

MARAM organisational embedding guide (OEG)

The OEG is designed to build existing resources available to support MARAM alignment such as the MARAM Practice Guides. The OEG was developed in direct response to feedback from departments and workforces requesting additional guidance to outline clear alignment tasks, with practical examples of MARAM alignment. The OEG addresses specific tasks and challenges with embedding MARAM into practice and organisational systems.

The intended audience for the OEG is organisational leaders and managers from framework organisations and/or organisations that are voluntarily aligning with MARAM. These organisations cover a wide range of sectors and sizes, all with different purposes. The OEG therefore must be sufficiently generic in form and advice, which allows for departments and organisations to adapt the resource as required, whilst maintaining enough detail to be of use to leaders.

The OEG takes the form of a three-step process:

- Step 1 – Complete an organisational self-audit tool. The MARAM organisational self-audit tool contains a series of milestones to work towards as part of MARAM alignment, with specific examples on how to reach each milestone. The examples are supported by resources, such as linking to relevant pages in MARAM Practice Guides or tools. Figure 1 below is an extract from the self-audit tool.

- Step 2 – Complete an implementation plan.A template Gantt chart is provided to organisations, with some examples included, to support the preparation of an implementation plan based on the activities they have highlighted in the MARAM self-audit tool as being the next priority.

- Step 3 – Undertake an implementation review. As part of continuous improvement, and to help inform a further self-audit, organisations are supported to review the success of implementation activities. This guide contains suggested questions and content for qualitative and quantitative reviews as well as case file audits.

“The new self-audit tool layout has been a revelation! I find it incredibly helpful and have been using it”.

Sector grants recipient

The Department of Premier and Cabinet’s Behavioural Insights Unit (BIU) is leading a project to support MARAM alignment, with engagement from FSV, two AOD service providers and VAADA. This project will develop tools to complement the MARAM OEG. The tools will be made available to all AOD services through VAADA and then scaled for wider release through sector grants and online distribution.

The OEG has gone some way to addressing the request by sector for greater clarity around the specific requirements of alignment. Alignment requirements will continue to be a focus through further developed tools such as this in progress by BIU, and work on a maturity model.

Intersectionality capacity building project

FSV is progressing work on an Intersectionality Capacity Building project which will develop a suite of resources to support capacity building to better understand, recognise and respond to the needs of people experiencing family violence underpinned by an intersectional approach. The resources will support a whole of organisational approach for different service sectors to adopt and embed an intersectional approach to their work in responding to family violence. These resources will complement organisations’ policies, procedures, practice guidance and tools with alignment to MARAM. It is anticipated that the resources will be released in the second half of 2020.

DJCS – Consumer Affairs Victoria (CAV)

Direct support has been provided to all Financial Counselling Program and Tenancy Assistance and Advocacy Program workforces to align their policies, procedures, practice guidance and tools with MARAM through a range of activities and resources, including:

- summarised and tailored MARAM Framework into a practice guide for each workforce

- developed customised MARAM risk assessment and management tools

- developed a COVID-19 pandemic family violence MARAM toolkit

- facilitated MARAM change discussion sessions with agencies to integrate MARAM tools into practice

Some of the activity’s agencies have reported over the past 12 months included:

- changes to the intake form to incorporate MARAM assessment questions

- staff regularly using the family violence evidence-based risk factors to identify risk

- development of a customised ‘Recognising and responding to family violence risk’ flow chart

- tailored MARAM tools, safety plans and practice guidance for each team within the organisation

- MARAM and FVISS have been added to the supervision template to prompt monthly reflective practice and case reviews

- family violence and MARAM professional development built into individual workplans

- most funded agencies have had facilitated team discussions with CAV about how to integrate MARAM tools into their work.

Forthcoming work to produce tailored resources and guidance will be informed by use of the OEG and will incorporate perpetrator focused practice guidance once released.

Victoria Police

Victoria Police has produced resources which assist in representing the broad range of experiences in family violence response for diverse communities:

- the Family violence safety notice booklet explains what constitutes family violence, what is a family violence safety notice and the importance of the standard conditions in the safety notice

- the Family violence: what police do information sheets explain Victoria Police’s response to family violence. They have been developed for victims of family violence, perpetrators of family violence and, people and/or services supporting them

- the Family violence: technical terms bilingual tool helps communication when talking about family violence and using interpreters

- a suite of videos in multiple languages(opens in a new window) to encourage people from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities to seek help if they are experiencing family violence, available at https://www.police.vic.gov.au/family-violence.

The new Victoria Police Family Violence Report (FVR – previously known as the L17 form) was deployed statewide on 22 July 2019. Developed in partnership with Swinburne University and Forensicare, in response to the Coroner’s findings of the Luke Batty Inquest and the Royal Commission, the FVR is a question-based, scored risk assessment tool for the initial police response to family violence incidents.

The completed FVR produces a score that is indicative of the likelihood of future family violence reported to police. This information guides the police response and is the basis for triage of high-risk family violence cases for proactive risk management and specialist response by the Family Violence Investigation Units (FVIUs). The FVR includes common risk factors identified in the MARAM Framework.

Practice guidance and online training were developed to support the introduction of the new FVR approach and to ensure it is used consistently. To ensure consistency in the application of the new FVR, mandatory force-wide face to face training for the deployment of the new FVR was undertaken: 83 per cent of Victoria Police’s workforce including up to the rank of superintendent have completed the training. Family Violence Training Officers within each division are continuing to review practices and tailor education as needed within their local police area.

Victoria Police deployed a case prioritisation and response model (CPRM) statewide on 22 July 2019. The CPRM is a framework for FVIUs to identify and prioritise the highest risk cases and tailor risk management to prevent serious harm from recurring. The CPRM ensures consistency of practice across the 31 FVIUs and delivers evidence-based identification of medium and high-risk family violence cases. It ensures Victoria Police’s resources are focused on family violence cases where ongoing harm to victims is likely and where specialist policing responses will have the greatest impact.

DJCS – Corrections Victoria

A dedicated and comprehensive family violence library was developed and launched on the Community Correctional Services (CCS) Portal. The CCS portal is a central information sharing platform that can be accessed by all CCS staff containing practice guidelines, tools and resources including:

- Managing family violence in community correctional services practice guidelines to assist CCS staff with supervision of victim survivors and perpetrators

- the Family Violence Screening Tool, Brief Assessment Tool and Intermediate Assessment Tool – Victim Survivor to assist CCS staff who have identified someone at risk or subject to family violence. The tools are based on the evidence-based risk factors in the MARAM framework

- a Perpetrator Brief Assessment tool based on the MARAM evidence-based risk factors. This tool assists CCS staff in identifying key risk factors that can be incorporated into existing intervention planning

- in response to a shift to a remote service delivery model for all low risk offenders and offenders on reparation orders, COVID-19-specific practice guidance was introduced, which includes guidance on the management of perpetrators and victim survivors.

In addition to specific COVID-19 practice guidance, a Remote Service Delivery Consultation Panel was established. It comprises DJCS staff with expertise in case management practice and parole and court stream processes. The panel provides support and consultation to practitioners where there may be escalating risks and difficulties in accessing services or system issues during remote delivery for offenders at highest risk of reoffending. A high proportion of cases presented were family violence related.

Between 20 April 2020 and 6 August 2020,[15] 1,558 offenders were presented to the panel, of whom:

- approximately 41 per cent (646 offenders) were flagged as having family violence as an identified risk

- 131 matters were escalated to Victoria Police

- 129 offenders were referred to victim services

- 513 offenders were referred to family violence services.

Organisations funded by Corrections Victoria are also making progress in the production of resources and guidance for MARAM alignment. There has been a strong focus on mapping workforce roles and responsibilities, understanding training needs including embedding family violence as part of pre-service training, and embedding MARAM principles, pillars and responsibilities into the organisational culture. Additional COVID-19-specific guidance has also been developed by some organisations to assist staff to manage family violence issues and adapt service delivery.

As at the end of June 2020, Corrections Victoria had 45 funded organisations/service providers who are framework organisations.

Examples of how some of these organisations are aligning to MARAM through the development of resources and tools include:

- embedded the MARAM evidence-based risk factors into risk assessment and management tools

- aligned practices with broader concepts of intersectionality and gender-based drivers of family violence

- adapted training and support for student placements and tasked supervisors to support students to develop skills in working with family violence perpetrators and victim survivors

- introduced practice guidance, quick reference guides and practice tips that are consistent with MARAM, including instructions on record keeping and specific guidance to manage family violence during COVID-19 restrictions

- built FVISS and CISS into supervision templates and forms so that practitioners are prompted to factor the schemes and the possibility of sharing information into client case plans.

DHHS – Mental Health, Alcohol and other Drugs

DHHS is working with Turning Point, a national leader in addiction treatment, training and research, to review AOD intake and assessment tools, and accompanying clinician guides. The review, due for completion in late 2020, aims to identify amendments to best align these tools to MARAM. The AOD workforce will be offered training on these amendments. This is taking place at the same time as the Victorian Alcohol and Drug Collection (VADC) department is undertaking work to require AOD workers to record whether a client has experienced or used family violence. This data can be used to report on the prevalence of the experience or use of family violence by clients of AOD services. The proposed amendments to the VADC will also require AOD workers to record whether they have used the MARAM Framework or tools to inform their practice.

VAADA is creating a ‘one-site stop’ for family violence resources tailored to the AOD services workforce. Currently available are two navigator tools – decision trees that step out the actions an AOD worker should take when a client intake assessment indicates experience or use of family violence, or risk of family violence. The MARAM Navigator includes resources to use at each step, from screening at intake to conducting a risk assessment. The Family Violence Information Sharing Navigator uses a flow chart to assist AOD workers understand when to share information under either the Family Violence or Child Information Sharing Schemes, and what actions or considerations must be undertaken at each step.

The Chief Psychiatrist guidelines provide specialist advice and are used to inform practitioners and services about clinical issues related to the Mental Health Act 2014. The ‘Family violence: guideline and practice resource’ section includes advice about how to incorporate screening and risk assessment within routine mental health assessments, practice advice about how best to elicit information, and advice about how to respond appropriately when family violence is disclosed. The Chief Psychiatrist guidelines are expected to align to MARAM by 2021.

DHHS – Child Protection and care services

Child Protection, secure welfare services and Hurstbridge Farm have commenced work to align existing policies and procedures to MARAM and staff have been mapped to MARAM responsibilities. Child Protection continues to further develop its SAFER Children Risk Assessment Framework, which will be aligned with MARAM, although its implementation is delayed owing to the COVID-19 pandemic. In the interim, work has been undertaken to align existing Child Protection policies and procedures with MARAM. An implementation plan is being further developed for aligning Child Protection practice.

The Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency (VACCA) (which also delivers family services) has developed culturally appropriate MARAM risk assessments, safety plans and workforce delivery practices for the Aboriginal workforce and clients to reflect changes in workforce delivery. These have been updated to address issues related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

DHHS – Housing and Homelessness

DHHS updated the Home visits and inspections in public housing operational guideline to outline HSO’s MARAM responsibilities. The updates came into effect on 1 January 2020. The Homelessness Funding Guidelines now include the temporary COVID-19 Amendment to Homelessness Services Guidelines and Conditions of Funding. The amendment came into effect in March 2020 in response to the impacts of COVID-19 on people’s living arrangements. The amendment is a live document and is being updated each time directions and restrictions change. The amendment includes a section on ‘family violence during self-isolation’, with links to MARAM Practice Guides.

Resources, such as guides on how to use the MARAM Screening and Identification tool, fact sheets about the screening and identification responsibilities, and the integration of the Screening and Identification Tool into existing Housing systems, are being developed to support the Housing workforce to meet their obligations under MARAM and the information sharing schemes.

The Council for Homeless Persons (CHP) has created role specific MARAM alignment practice guidance for homelessness services. Guidance for executives focuses on the broad objectives and cultural change that MARAM aims to achieve. Management guidance provides a tailored checklist of relevant organisational policies and procedures that may require review and adaptation, as well as advice about workforce training. Practitioner guidance aims to further develop practitioner understanding of how the information sharing schemes can benefit clients, as well as links to relevant general MARAM resources.

Work is being undertaken to incorporate MARAM tools into Homelessness IT systems, including the Specialist Homelessness Information Platform (SHIP), Secure Residential Services, The Salvation Army Service and the Mission Information System databases.

DHHS – MCH services

DHHS developed MARAM practice guidance that outlines MCH practitioners’ MARAM responsibilities, and the data collection approach for the MCH workforce. The MARAM practice guidance was circulated to all MCH practitioners by the Municipal Association of Victoria (MAV) in early 2020. DHHS will continue to work with MAV to communicate with and support MCH practitioners with MARAM practice.

MAV has created the MARAM Information Sharing Advisory Group (Advisory Group), comprising MCH and family services coordinators and managers. MAV provides advocacy and support to MCH services and councils to improve capacity and confidence in implementing MARAM.

MAV has released a resource package to support MCH services align with MARAM. The package includes:

- Child Information Sharing and Family Violence Information Sharing Toolkit for Maternal and Child Health Services

- correspondence templates for making a request, proactively sharing, responding to a request, or updating a responder

- documentation of how council policies, procedures and guidelines are expected align to MARAM.

Work is underway to align the Child Development Information System (CDIS), which is used by MCH practitioners to record child health data, with MARAM. The CDIS is anticipated to be fully aligned with MARAM by October 2020. Alignment will enable MCH practitioners to record family violence information, including whether it was requested, received, or proactively shared.

Phase 2 preparations

Work has commenced on preparing hospitals for prescription in Phase 2.

The Strengthening Hospital Responses to Family Violence (SHRFV) team, established in 2014 and led by the Royal Women’s Hospital and Bendigo Health, aims to support best practice responses to family violence in health care settings. Based on the experience of implementing the SHRFV model across Victorian hospitals, a range of resources and tools were developed to support Victorian public hospitals to implement the SHRFV model. This suite of materials also includes specialised content and is known as the SHRFV tool kit.

The SHRFV toolkit was developed prior to the development of the MARAM Framework and Practice Guides, and therefore there is a need to align the toolkit with MARAM in order to support hospitals. Ahead of the commencement of Phase 2, the Royal Women’s Hospital and Bendigo Health received funding from FSV to align the toolkit to MARAM.

In May 2020, SHRFV published MARAM alignment for hospitals and health services. This document provides guidance and advice to hospitals and health services, including designated Mental Health, to develop their MARAM Action Plan. The MARAM Action Plan should demonstrate how the four MARAM pillars will be incorporated into existing policies, procedures and practice. Seven supporting resources accompany the MARAM alignment for hospitals and health services as follows:

- Supporting resource A: Workforce mapping for MARAM Alignment outlines how to map the workforce to the 10 MARAM responsibilities

- Supporting resource B: MARAM consultation questions to inform the development of the MARAM Action Plan

- Supporting resource C: Resource audit tool to assist the audit of existing policies, procedures etc. to ensure MARAM alignment

- Supporting resource D: Organisation audit tool to assist the audit organisational structures and systems against the alignment requirements of MARAM

- Supporting resource E: Facilitating collaborative practice provides guidance on establishing or strengthening partnerships

- Supporting resource F: MARAM Alignment Action Plan template

- Supporting resource G: Briefing paper provides an example briefing paper for leaders that can accompany the final MARAM alignment action plan and workforce mapping

Portfolio examples – collaborative practice

FSV – The Orange Door

As an entry point into the family violence system, The Orange Door receives information from Victoria Police through L17s (now FVRs). The Orange Door staff take steps to assess family violence risk and coordinate a multiagency service delivery to manage immediate risk.

Case study: The Orange Door, Victoria Police, CIP, Community Health Services

The Orange Door received two L17s in respect of Julie (74 years) and her son, Paul (53 years), who were residing together. Paul was identified as experiencing mental health issues and harmful use of alcohol. Julie had previously obtained an intervention order against Paul, but he had since returned to live with her.

When The Orange Door contacted Julie following the latest incident, Paul answered the phone and Julie declined a need for assistance. A risk was identified that Julie may be prevented from accessing help.

The Orange Door completed a CIP request which provided a long history of criminal offending by Paul, multiple periods in prison, significant mental health concerns and serious family violence offending. A consultation occurred with the Advanced Family Violence Practice Leader who recommended a request for health information. This identified Julie had regular engagement with a health service. The Orange Door contacted the health service who were then able to facilitate a discussion with Julie in a safe location. This provided an opportunity for Julie to receive the support she needed.

DJCS – Corrections and Justice

Many organisations have used MARAM to:

- identify gaps in risk assessment information

- make decisions about requests and voluntary information sharing with other services

- undertake needs assessments, develop safety plans for clients and refer them to other services

- establish collaborative practices with family violence specialist services, generalist services, Victoria Police and community organisations.

An example of how organisations in the Corrections and Justice portfolio are collaborating in practice is demonstrated in the following case study:

Case study: DJCS, DHHS

An Aboriginal man was released on parole. His offence was related to family violence against his partner. He had a history of drug use. A family violence intervention order was in force and there was DHHS Child Protection involvement with his children.

The man is participating in ReConnect provided by the Australian Community Support Organisation (ACSO). ReConnect provides targeted, intensive (up to 12 months) post-release reintegration outreach support for prisoners assessed as having high-level transitional needs.

ACSO Reconnect is working collaboratively with the man’s Aboriginal Justice Worker, relevant AOD treatment service and his CCS practitioner to ensure wraparound services are available to him.

This keeps the person using family violence in view, and, where required for risk assessment and management, information will be shared to keep the victim survivor safe.

DJCS – Youth Justice

Key activities that were reported by funded organisations include:

- involvement in sector communities of practice, The Orange Door presentations or other forums, either family violence practice specific or generalist

- seeking specialist advice from family violence services or community-based Child Protection practitioners

- development of organisational memorandum of understandings (MOUs), information sharing flow charts and other resources to ensure staff are confident and clear in their capacity to share information and work collaboratively

- nominating organisational MARAM champions to provide extra support to operational staff to identify relevant family violence risk information within the context of their day-to-day work.

Case study: DJCS, Child Protection, Victoria Police, FSV

A regional Youth Justice Community Support Service provider outlined a case where the organisation worked with Youth Justice, Child Protection, Victoria Police, Corrections Victoria, family violence services and other services to support a young person to engage safety planning, make a report to police and successfully leave a violent relationship.

The provider reflected that the collaborative work of the care team over an extended period was able to keep the young person safe and keep them engaged with services until they were ready to formally pursue charges and leave the relationship.

DJCS – Consumer Affairs Victoria

All FCP organisations participate in regular collaborative practice with other programs internally, and with family violence and other services externally. Collaborative working models have been impacted in 2020 by COVID-19 and remote working.

Examples of enhanced collaborative practice in the last 12 months include:

- worker co-located at local family violence service one day a week

- greater identification of family violence has led to more secondary consultations with in-house family violence programs

- workers are now asking for details of risk assessments when receiving family violence referrals so that the client does not have to retell their story

- workers are providing details from their risk assessments when referring clients to other services so that there is a clearer picture of risk

- workers have access to existing safety planning so can focus resources on resolving the client’s financial issues, whilst maintaining ongoing risk assessment and reviews of safety planning.

Case Study – DJCS

A mother was referred to a financial counsellor by a family violence worker. The mother had left an abusive relationship but had incurred telephone and utility debts. The financial counsellor was able to manage these debts through waivers and payment plans. An insurance company had breached the mother’s privacy, which potentially threatened her safety, and a compensation claim was negotiated. A Flexible Support Package for furniture and a laptop for her daughter’s schooling was applied for from the regional specialist family violence agency. The financial counsellor worked collaboratively with the family violence case worker to ensure client’s safety planning was in place and the client’s relocation was supported.

DJCS – Victim services, support and reform

The introduction of MARAM, and the resulting uplift in the identification of relevant family violence risk information has seen an increase in information sharing and collaboration across all the Victim Assistance Programs (VAPs).

Staff at Cohealth report being more aware of how to determine the predominant aggressor in the context of family violence. They are working more closely with family violence counselling and case management teams and have improved processes through co-case management to deliver better continuity of care for women with high or complex needs who are family violence victim survivors.

The VAP team at Eastern Access Community Health (EACH) have reported developing more supportive and collaborative working relationships with the EACH family violence counselling team, the EACH family violence specialist advisor and the regional specialty services for family violence.

Anglicare Victoria has strong working relationships with specialist family violence services, The Orange Door, Child FIRST, headspace, out of home care, family violence financial counsellors, and gamblers help therapeutic counsellors. Due to these established relationships, information is being shared under existing processes rather than under the CISS or FVISS. Anglicare Victoria has reviewed all MOUs (or service agreements) with external stakeholders to ensure the MARAM principles are included.

Windemere noted an increase in information sharing under FVISS and CISS and increased collaboration across program areas within Windermere, including more secondary consultations.

Case study – DJCS, Victoria Police, FSV

A man presented to a VAP office as a victim of family violence, claiming he had a previous intervention order against his female ex-partner. The man then disclosed that the same ex-partner had recently taken an IVO out against him and had been in contact with a local family violence service. Information provided to the VAP by the Victims of Crime Helpline listed the man as a victim survivor on three L17 referrals, but a different ex-partner was listed as the perpetrator. The VAP suspected the man may have been the predominant aggressor to both ex-partners. The VAP made an information sharing request to the local family violence service for any information pertaining to the man and his two ex-partners to assess risk.

The family violence service had a history of one ex-partner as a victim survivor and the man as a perpetrator over two years. The service shared knowledge that the man was currently continuing to perpetrate family violence against his ex-partner, which they determined using the MARAM Comprehensive Risk Assessment Tool. The family violence service disclosed that they were supporting her to manage the risk and her safety through case management and brokerage for security expenses.

The man was informed that the VAP could not provide support, and he was instead was referred to his local community legal service for court support and to his GP for counselling.

DHHS – Mental Health, Alcohol and other Drugs and Homelessness

VAADA has partnered with NTV and the Council to Homeless Persons to create an online, animated case study that demonstrates best practice information sharing across sectors and how to manage family violence.

The animation demonstrates that different workforces have different considerations when sharing information, what these might be, and how they interact with the considerations and expectations that may exist in other workforces. It also shows the benefits to the client when information is shared.

VAADA is supporting government in developing tools specifically for AOD services that are aligned with MARAM. The tools are expected to be made available to all AOD services through VAADA and to other non-AOD workforces in a generic format.

Portfolio examples – information sharing

The importance of information sharing is reflected in MARAM responsibility 6. Information sharing between services was identified by the Royal Commission as essential for keeping a victim survivor safe and a perpetrator in view and accountable as part of collaborative practice.

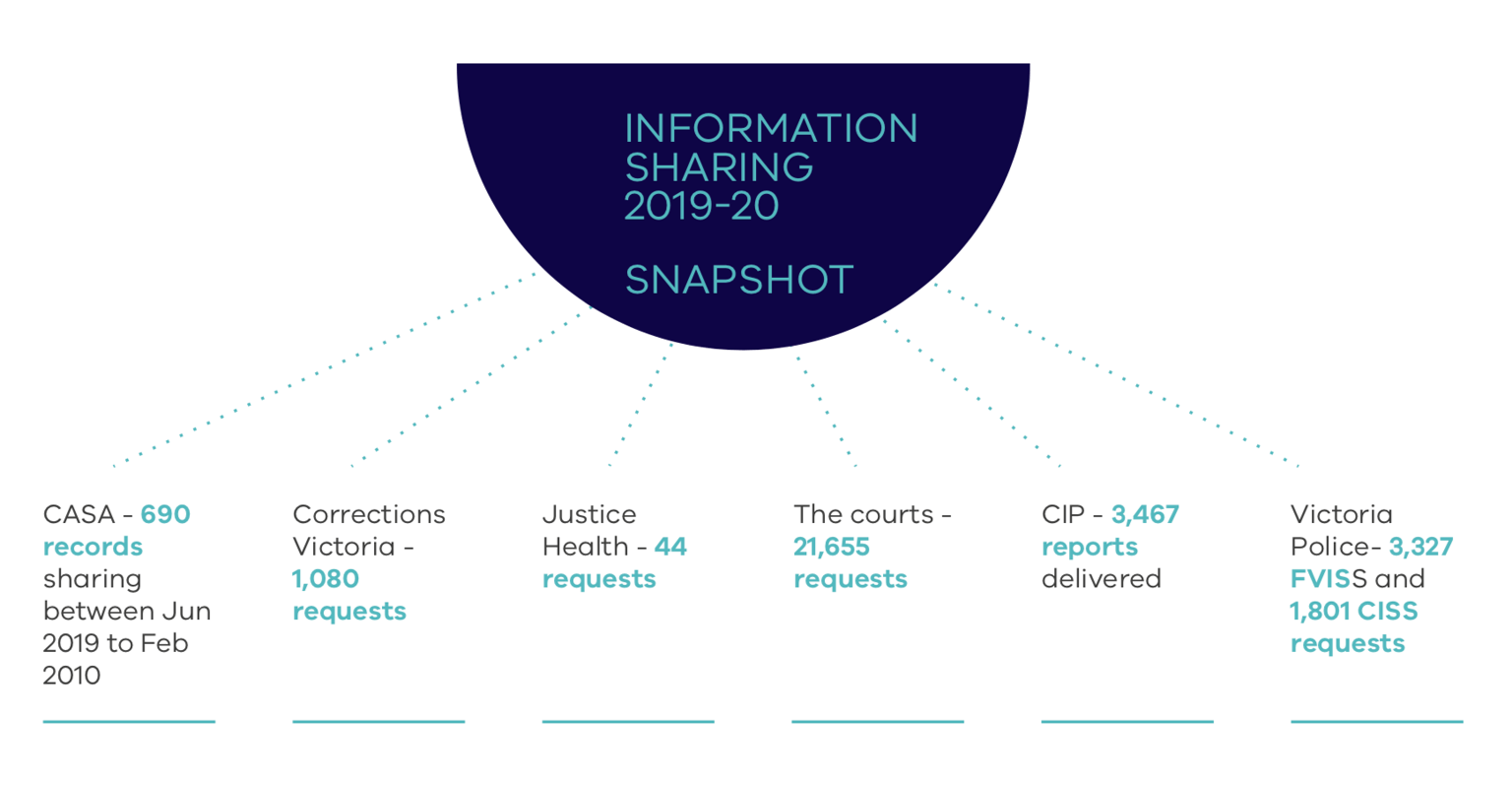

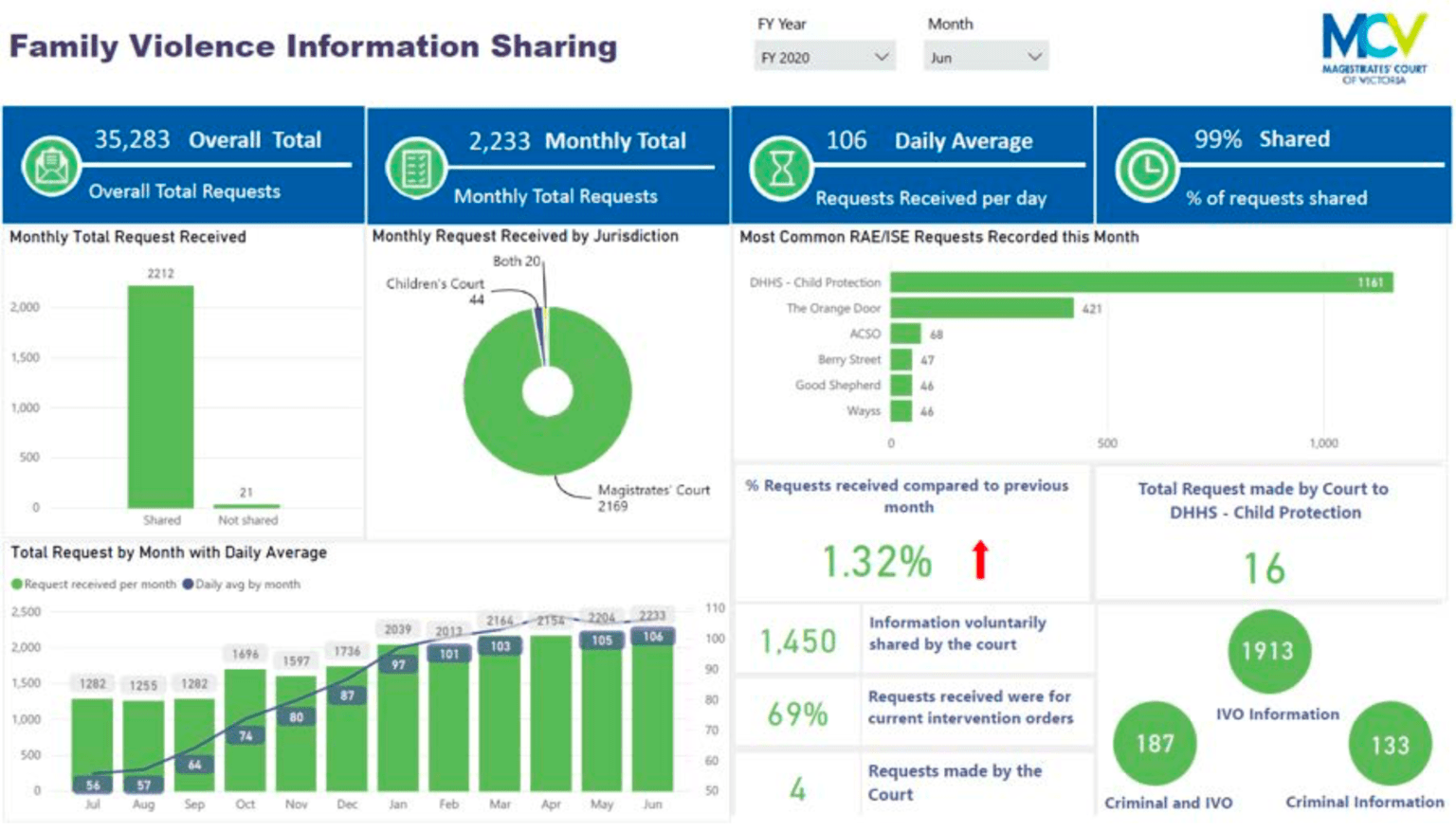

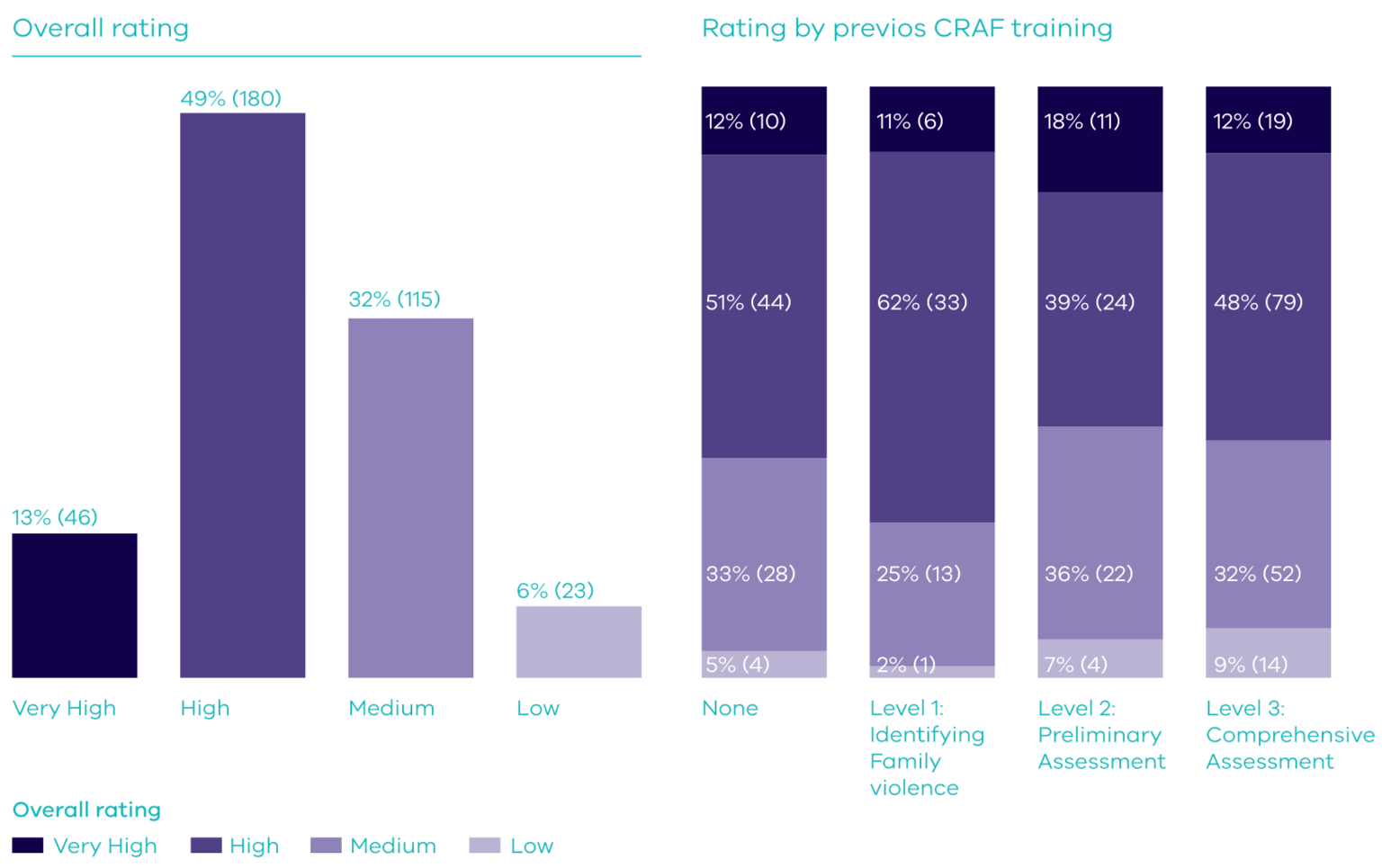

The figure below highlights examples of information sharing taking place.[16]

FSV, DHHS and DJCS – the Central Information Point (CIP)

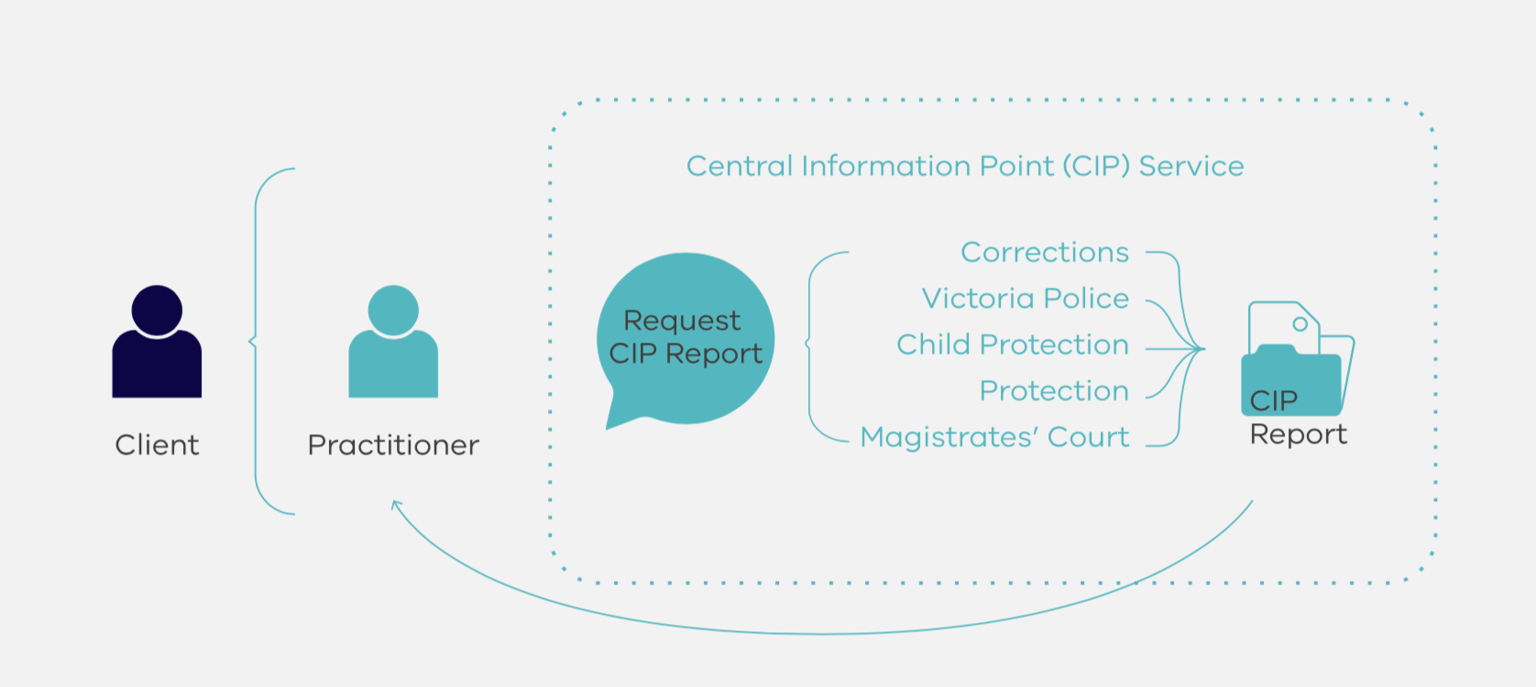

The CIP is a unique and targeted model of multiagency information sharing about perpetrators to inform risk assessment and management. CIP aligns with MARAM responsibility 6 (contribute to information sharing), responsibility 9 (contribute to coordinated risk management) and responsibility 10 (collaborate for ongoing risk assessment and risk management).

CIP brings together perpetrator information from Victoria Police, Courts MCV, Corrections Victoria and DHHS – specifically Child Protection.

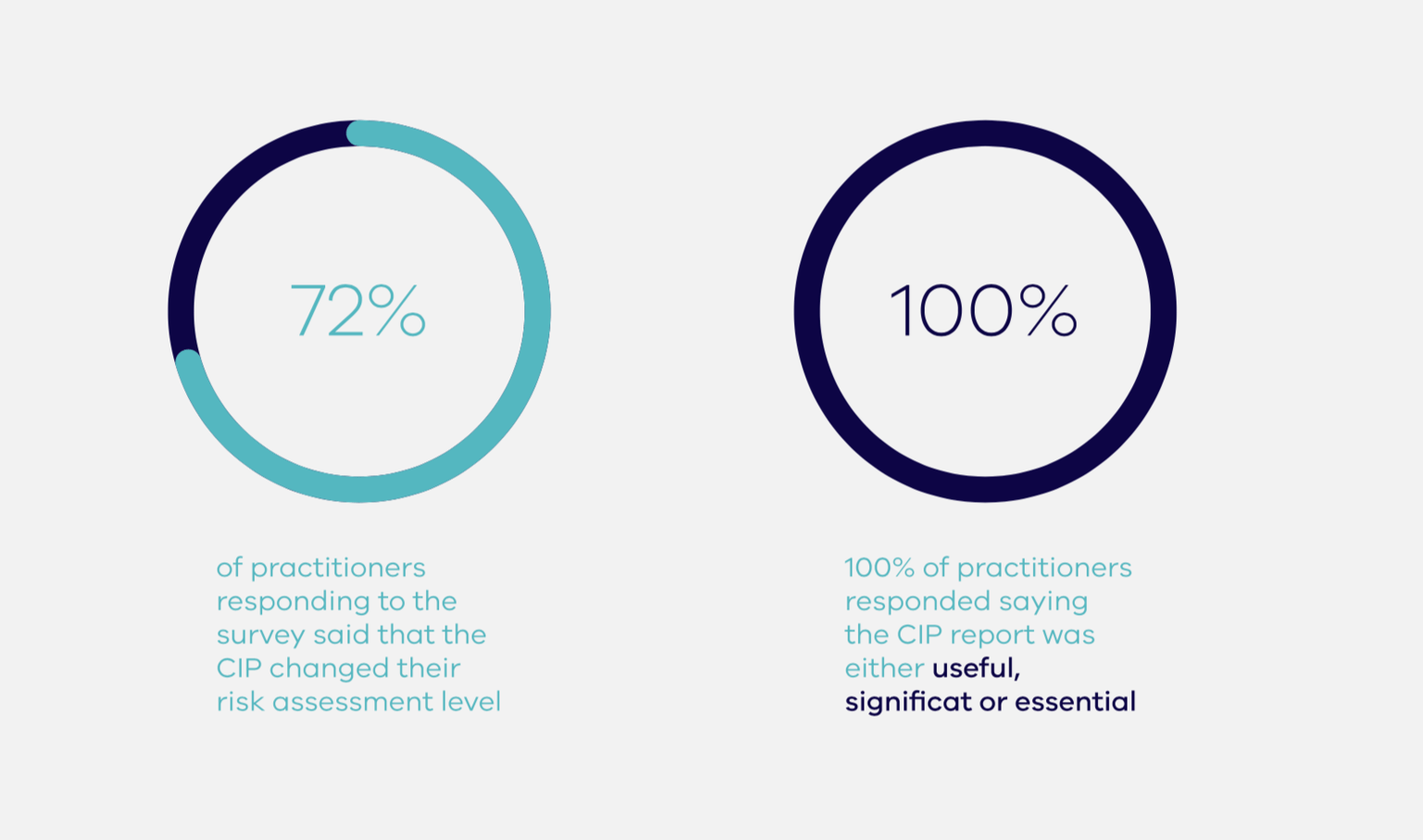

The CIP reports continue to provide family violence practitioners with timely access to critical consolidated information to assess and manage risk posed by alleged perpetrators or perpetrators of family violence. CIP reports are currently available to The Orange Door and Berry Street.

CIP staff have attended tailored MARAM training which has helped to further develop their understanding and assessment of family violence risk factors in the data they review and share. On 27 March 2020, the CIP team relocated to work from home. As a CIP report is a collaborative process of pulling together the four data sets to indicate the level of risk from a perpetrator’s patterns of behaviour, systems have been modified to ensure that CIP staff can continue to work collaboratively to effectively share information complete the CIP report. This transition has meant that frontline practitioners continue to be supported to assess and manage risk of family violence.

In 2020–21, FSV has planned actions to support the ongoing implementation and alignment of the CIP to MARAM, including:

- aligning the CIP request form to MARAM risk factors

- enhancing collaborative risk assessment and management practice through system integration and enhancement, policy development and operational support.

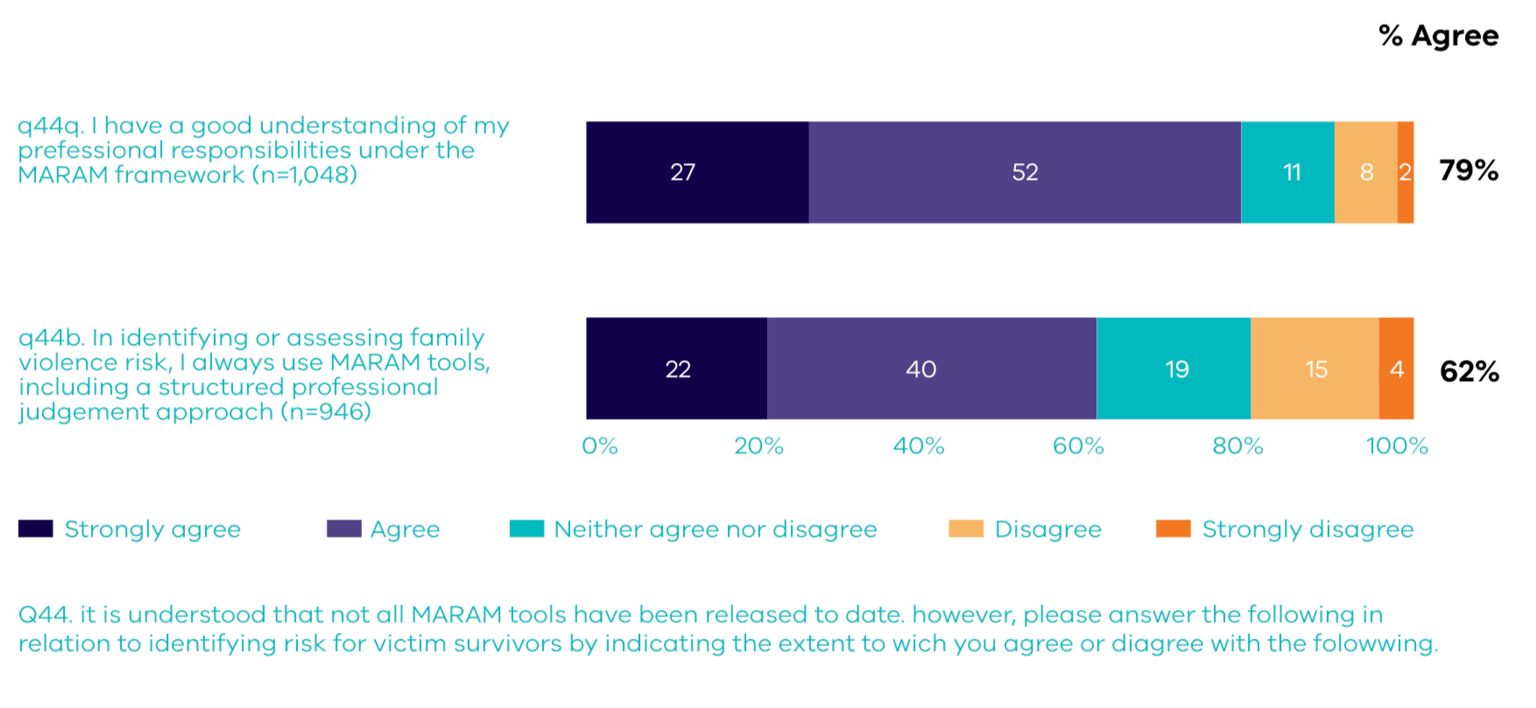

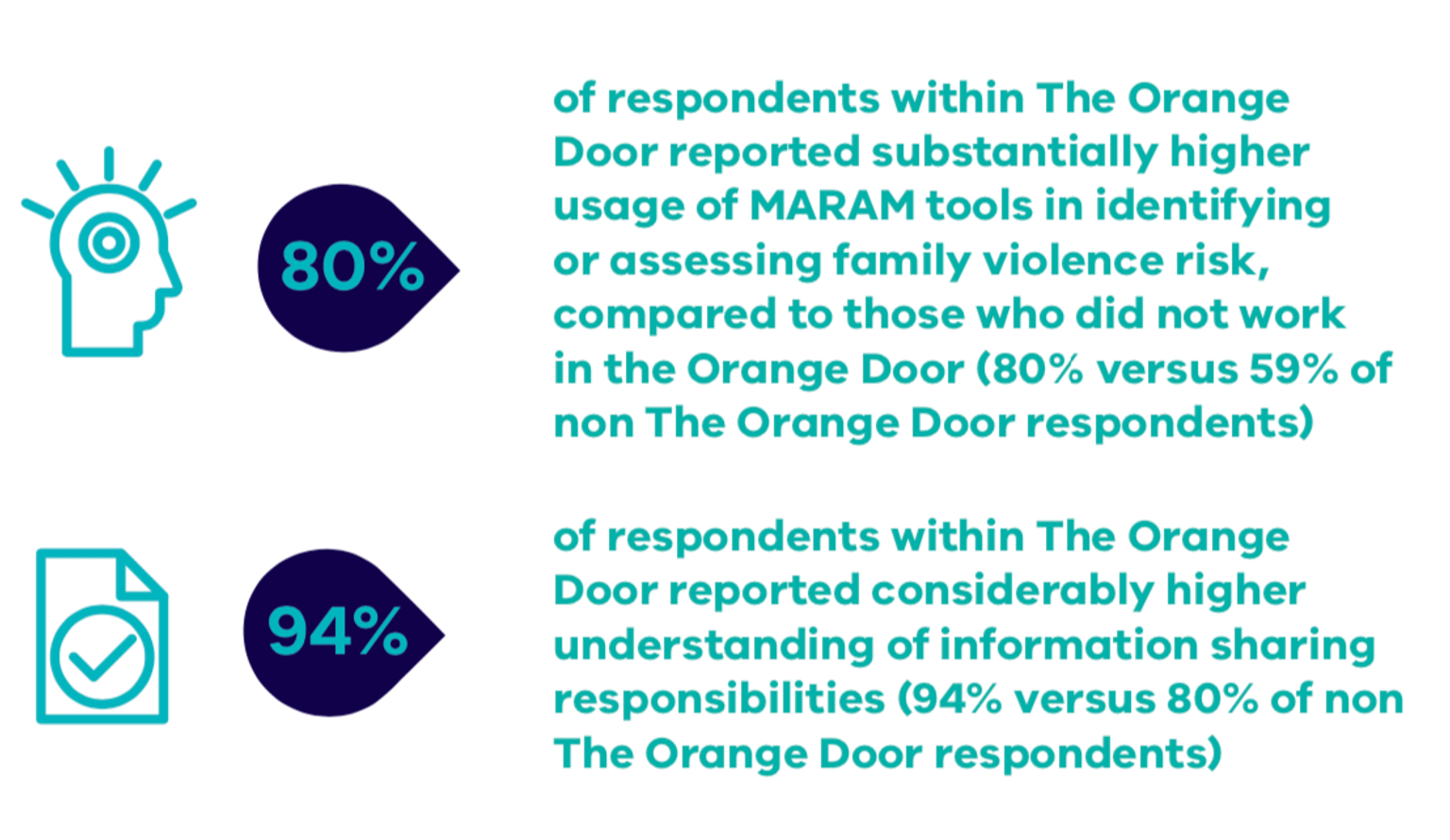

CIP case study 1 – FSV, Child Protection