2. Facilitate consistent and collaborative practice

FSV have a lead role in producing centralised resources. Organisations are guided by tailored resources developed by departments and sector peaks that support a change in practice.

Key highlights

Government-led highlights:

- The victim survivor focused Practice Guides and tools support professionals in their screening, identification, risk assessment and risk management practice, and were publicly released in July 2019.

- MARAM Practice Notes and factsheets to support targeted responses to family violence during the COVID-19 pandemic were released between March and June 2020.

- The organisational embedding guide (OEG) was released online in June 2020 to support organisations in their alignment to MARAM.

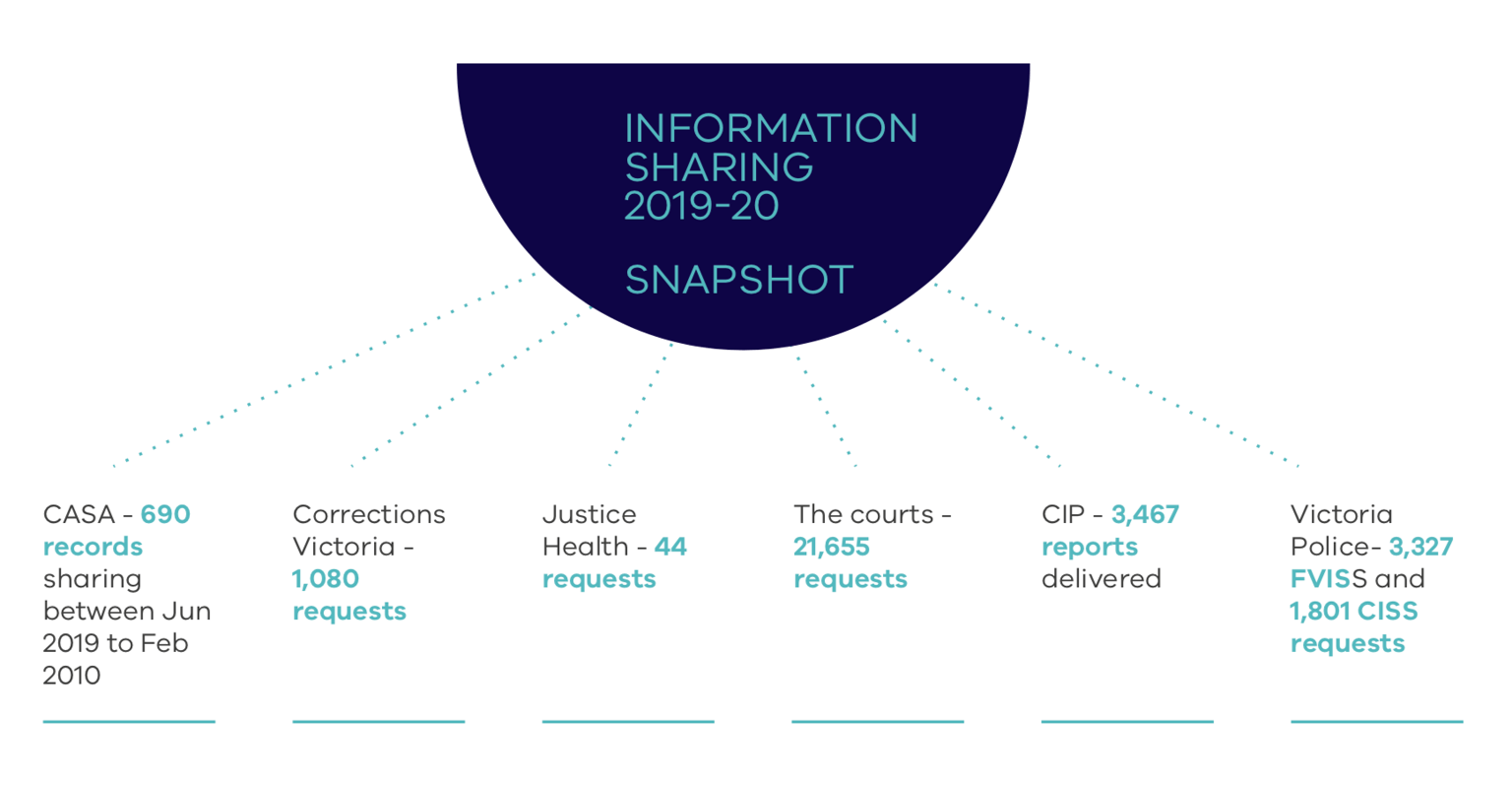

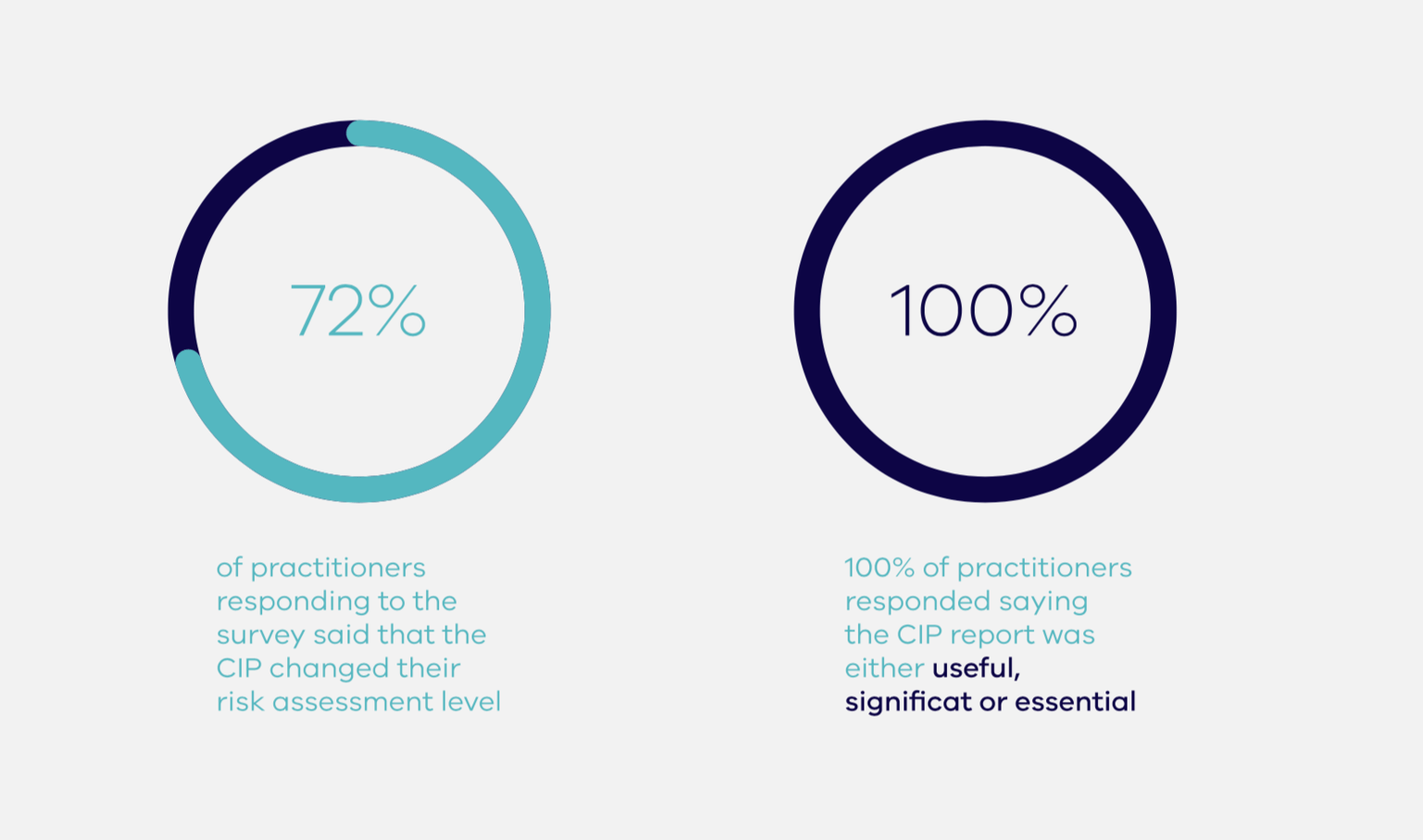

- The CIP delivered 3,467 reports.

Sector-led highlights:

- NTV provided individualised support for organisations in the alignment of their policies, processes and practice guidance.

- DV Vic redeveloped the Specialist Family Violence Services Code of Practice to align with the MARAM Framework.

- The Centre for Excellence in Child and Family Welfare (CECFW) developed a range of resources for Child and Family Services, including Child FIRST, and care services sectors, including a series of podcasts featuring interviews and Q&As with leaders in the field, as well as information sheets.

Portfolio examples – resources and tools for consistent practice

MARAM tools and Practice Guides

The victim survivor focused Practice Guides and tools, released in July 2019, support professionals in understanding their risk assessment and risk management practice under the MARAM Framework. There is a foundational knowledge guide, and individual Practice Guides for each MARAM responsibility.

The resources include risk assessment tools and safety plan templates for adults, and children and young people which can be tailored and/or embedded into existing tools by services.

Work is now being undertaken to develop perpetrator focused Practice Guides and tools. These will replicate the same structure as the victim survivor focused Practice Guides, supporting practice across the 10 MARAM responsibilities.

The perpetrator focused program of work includes:

- non-specialist perpetrator workforce guides and tools (such as Mental Health, AOD, Housing/Homelessness and Child Protection) to assess risk at an intermediate level

- specialist perpetrator workforce guides and tools (such as men’s behaviour change practitioners) to assess risk at a comprehensive level.

FSV is collaborating with NTV and other experts on the Practice Guide development, and with Curtin University on the developments of the tools. It is anticipated that perpetrator focused Practice Guides and tools (specialist and non-specialist will all be released by early 2021.

In conjunction with the CECFW, FSV will continue to build the evidence to respond earlier to adolescents who use family violence. FSV is seeking to strengthen the capacity of workforces to respond to adolescents which will include embedding further guidance on adolescents who use family violence into the next Phase of MARAM Practice Guides.

MARAM organisational embedding guide (OEG)

The OEG is designed to build existing resources available to support MARAM alignment such as the MARAM Practice Guides. The OEG was developed in direct response to feedback from departments and workforces requesting additional guidance to outline clear alignment tasks, with practical examples of MARAM alignment. The OEG addresses specific tasks and challenges with embedding MARAM into practice and organisational systems.

The intended audience for the OEG is organisational leaders and managers from framework organisations and/or organisations that are voluntarily aligning with MARAM. These organisations cover a wide range of sectors and sizes, all with different purposes. The OEG therefore must be sufficiently generic in form and advice, which allows for departments and organisations to adapt the resource as required, whilst maintaining enough detail to be of use to leaders.

The OEG takes the form of a three-step process:

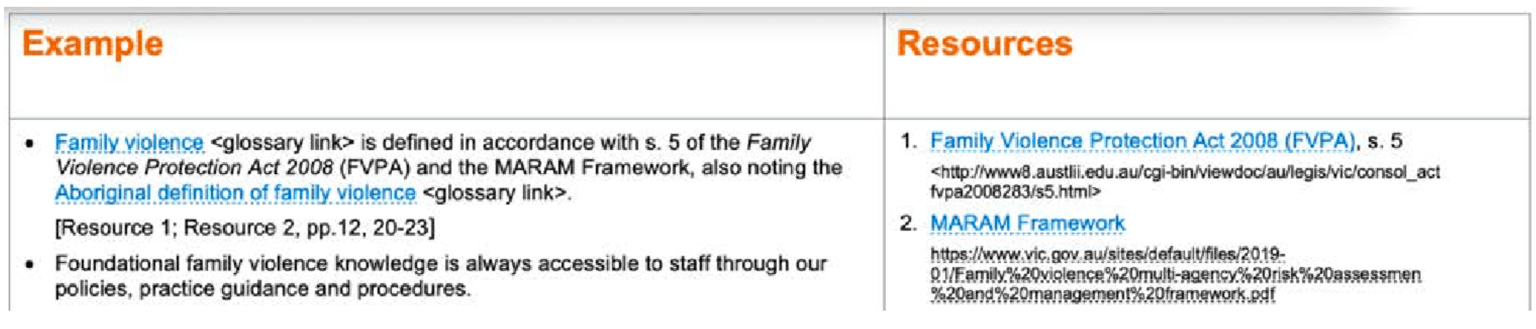

- Step 1 – Complete an organisational self-audit tool. The MARAM organisational self-audit tool contains a series of milestones to work towards as part of MARAM alignment, with specific examples on how to reach each milestone. The examples are supported by resources, such as linking to relevant pages in MARAM Practice Guides or tools. Figure 1 below is an extract from the self-audit tool.

- Step 2 – Complete an implementation plan.A template Gantt chart is provided to organisations, with some examples included, to support the preparation of an implementation plan based on the activities they have highlighted in the MARAM self-audit tool as being the next priority.

- Step 3 – Undertake an implementation review. As part of continuous improvement, and to help inform a further self-audit, organisations are supported to review the success of implementation activities. This guide contains suggested questions and content for qualitative and quantitative reviews as well as case file audits.

“The new self-audit tool layout has been a revelation! I find it incredibly helpful and have been using it”.

Sector grants recipient

The Department of Premier and Cabinet’s Behavioural Insights Unit (BIU) is leading a project to support MARAM alignment, with engagement from FSV, two AOD service providers and VAADA. This project will develop tools to complement the MARAM OEG. The tools will be made available to all AOD services through VAADA and then scaled for wider release through sector grants and online distribution.

The OEG has gone some way to addressing the request by sector for greater clarity around the specific requirements of alignment. Alignment requirements will continue to be a focus through further developed tools such as this in progress by BIU, and work on a maturity model.

Intersectionality capacity building project

FSV is progressing work on an Intersectionality Capacity Building project which will develop a suite of resources to support capacity building to better understand, recognise and respond to the needs of people experiencing family violence underpinned by an intersectional approach. The resources will support a whole of organisational approach for different service sectors to adopt and embed an intersectional approach to their work in responding to family violence. These resources will complement organisations’ policies, procedures, practice guidance and tools with alignment to MARAM. It is anticipated that the resources will be released in the second half of 2020.

DJCS – Consumer Affairs Victoria (CAV)

Direct support has been provided to all Financial Counselling Program and Tenancy Assistance and Advocacy Program workforces to align their policies, procedures, practice guidance and tools with MARAM through a range of activities and resources, including:

- summarised and tailored MARAM Framework into a practice guide for each workforce

- developed customised MARAM risk assessment and management tools

- developed a COVID-19 pandemic family violence MARAM toolkit

- facilitated MARAM change discussion sessions with agencies to integrate MARAM tools into practice

Some of the activity’s agencies have reported over the past 12 months included:

- changes to the intake form to incorporate MARAM assessment questions

- staff regularly using the family violence evidence-based risk factors to identify risk

- development of a customised ‘Recognising and responding to family violence risk’ flow chart

- tailored MARAM tools, safety plans and practice guidance for each team within the organisation

- MARAM and FVISS have been added to the supervision template to prompt monthly reflective practice and case reviews

- family violence and MARAM professional development built into individual workplans

- most funded agencies have had facilitated team discussions with CAV about how to integrate MARAM tools into their work.

Forthcoming work to produce tailored resources and guidance will be informed by use of the OEG and will incorporate perpetrator focused practice guidance once released.

Victoria Police

Victoria Police has produced resources which assist in representing the broad range of experiences in family violence response for diverse communities:

- the Family violence safety notice booklet explains what constitutes family violence, what is a family violence safety notice and the importance of the standard conditions in the safety notice

- the Family violence: what police do information sheets explain Victoria Police’s response to family violence. They have been developed for victims of family violence, perpetrators of family violence and, people and/or services supporting them

- the Family violence: technical terms bilingual tool helps communication when talking about family violence and using interpreters

- a suite of videos in multiple languages(opens in a new window) to encourage people from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities to seek help if they are experiencing family violence, available at https://www.police.vic.gov.au/family-violence.

The new Victoria Police Family Violence Report (FVR – previously known as the L17 form) was deployed statewide on 22 July 2019. Developed in partnership with Swinburne University and Forensicare, in response to the Coroner’s findings of the Luke Batty Inquest and the Royal Commission, the FVR is a question-based, scored risk assessment tool for the initial police response to family violence incidents.

The completed FVR produces a score that is indicative of the likelihood of future family violence reported to police. This information guides the police response and is the basis for triage of high-risk family violence cases for proactive risk management and specialist response by the Family Violence Investigation Units (FVIUs). The FVR includes common risk factors identified in the MARAM Framework.

Practice guidance and online training were developed to support the introduction of the new FVR approach and to ensure it is used consistently. To ensure consistency in the application of the new FVR, mandatory force-wide face to face training for the deployment of the new FVR was undertaken: 83 per cent of Victoria Police’s workforce including up to the rank of superintendent have completed the training. Family Violence Training Officers within each division are continuing to review practices and tailor education as needed within their local police area.

Victoria Police deployed a case prioritisation and response model (CPRM) statewide on 22 July 2019. The CPRM is a framework for FVIUs to identify and prioritise the highest risk cases and tailor risk management to prevent serious harm from recurring. The CPRM ensures consistency of practice across the 31 FVIUs and delivers evidence-based identification of medium and high-risk family violence cases. It ensures Victoria Police’s resources are focused on family violence cases where ongoing harm to victims is likely and where specialist policing responses will have the greatest impact.

DJCS – Corrections Victoria

A dedicated and comprehensive family violence library was developed and launched on the Community Correctional Services (CCS) Portal. The CCS portal is a central information sharing platform that can be accessed by all CCS staff containing practice guidelines, tools and resources including:

- Managing family violence in community correctional services practice guidelines to assist CCS staff with supervision of victim survivors and perpetrators

- the Family Violence Screening Tool, Brief Assessment Tool and Intermediate Assessment Tool – Victim Survivor to assist CCS staff who have identified someone at risk or subject to family violence. The tools are based on the evidence-based risk factors in the MARAM framework

- a Perpetrator Brief Assessment tool based on the MARAM evidence-based risk factors. This tool assists CCS staff in identifying key risk factors that can be incorporated into existing intervention planning

- in response to a shift to a remote service delivery model for all low risk offenders and offenders on reparation orders, COVID-19-specific practice guidance was introduced, which includes guidance on the management of perpetrators and victim survivors.

In addition to specific COVID-19 practice guidance, a Remote Service Delivery Consultation Panel was established. It comprises DJCS staff with expertise in case management practice and parole and court stream processes. The panel provides support and consultation to practitioners where there may be escalating risks and difficulties in accessing services or system issues during remote delivery for offenders at highest risk of reoffending. A high proportion of cases presented were family violence related.

Between 20 April 2020 and 6 August 2020,[15] 1,558 offenders were presented to the panel, of whom:

- approximately 41 per cent (646 offenders) were flagged as having family violence as an identified risk

- 131 matters were escalated to Victoria Police

- 129 offenders were referred to victim services

- 513 offenders were referred to family violence services.

Organisations funded by Corrections Victoria are also making progress in the production of resources and guidance for MARAM alignment. There has been a strong focus on mapping workforce roles and responsibilities, understanding training needs including embedding family violence as part of pre-service training, and embedding MARAM principles, pillars and responsibilities into the organisational culture. Additional COVID-19-specific guidance has also been developed by some organisations to assist staff to manage family violence issues and adapt service delivery.

As at the end of June 2020, Corrections Victoria had 45 funded organisations/service providers who are framework organisations.

Examples of how some of these organisations are aligning to MARAM through the development of resources and tools include:

- embedded the MARAM evidence-based risk factors into risk assessment and management tools

- aligned practices with broader concepts of intersectionality and gender-based drivers of family violence

- adapted training and support for student placements and tasked supervisors to support students to develop skills in working with family violence perpetrators and victim survivors

- introduced practice guidance, quick reference guides and practice tips that are consistent with MARAM, including instructions on record keeping and specific guidance to manage family violence during COVID-19 restrictions

- built FVISS and CISS into supervision templates and forms so that practitioners are prompted to factor the schemes and the possibility of sharing information into client case plans.

DHHS – Mental Health, Alcohol and other Drugs

DHHS is working with Turning Point, a national leader in addiction treatment, training and research, to review AOD intake and assessment tools, and accompanying clinician guides. The review, due for completion in late 2020, aims to identify amendments to best align these tools to MARAM. The AOD workforce will be offered training on these amendments. This is taking place at the same time as the Victorian Alcohol and Drug Collection (VADC) department is undertaking work to require AOD workers to record whether a client has experienced or used family violence. This data can be used to report on the prevalence of the experience or use of family violence by clients of AOD services. The proposed amendments to the VADC will also require AOD workers to record whether they have used the MARAM Framework or tools to inform their practice.

VAADA is creating a ‘one-site stop’ for family violence resources tailored to the AOD services workforce. Currently available are two navigator tools – decision trees that step out the actions an AOD worker should take when a client intake assessment indicates experience or use of family violence, or risk of family violence. The MARAM Navigator includes resources to use at each step, from screening at intake to conducting a risk assessment. The Family Violence Information Sharing Navigator uses a flow chart to assist AOD workers understand when to share information under either the Family Violence or Child Information Sharing Schemes, and what actions or considerations must be undertaken at each step.

The Chief Psychiatrist guidelines provide specialist advice and are used to inform practitioners and services about clinical issues related to the Mental Health Act 2014. The ‘Family violence: guideline and practice resource’ section includes advice about how to incorporate screening and risk assessment within routine mental health assessments, practice advice about how best to elicit information, and advice about how to respond appropriately when family violence is disclosed. The Chief Psychiatrist guidelines are expected to align to MARAM by 2021.

DHHS – Child Protection and care services

Child Protection, secure welfare services and Hurstbridge Farm have commenced work to align existing policies and procedures to MARAM and staff have been mapped to MARAM responsibilities. Child Protection continues to further develop its SAFER Children Risk Assessment Framework, which will be aligned with MARAM, although its implementation is delayed owing to the COVID-19 pandemic. In the interim, work has been undertaken to align existing Child Protection policies and procedures with MARAM. An implementation plan is being further developed for aligning Child Protection practice.

The Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency (VACCA) (which also delivers family services) has developed culturally appropriate MARAM risk assessments, safety plans and workforce delivery practices for the Aboriginal workforce and clients to reflect changes in workforce delivery. These have been updated to address issues related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

DHHS – Housing and Homelessness

DHHS updated the Home visits and inspections in public housing operational guideline to outline HSO’s MARAM responsibilities. The updates came into effect on 1 January 2020. The Homelessness Funding Guidelines now include the temporary COVID-19 Amendment to Homelessness Services Guidelines and Conditions of Funding. The amendment came into effect in March 2020 in response to the impacts of COVID-19 on people’s living arrangements. The amendment is a live document and is being updated each time directions and restrictions change. The amendment includes a section on ‘family violence during self-isolation’, with links to MARAM Practice Guides.

Resources, such as guides on how to use the MARAM Screening and Identification tool, fact sheets about the screening and identification responsibilities, and the integration of the Screening and Identification Tool into existing Housing systems, are being developed to support the Housing workforce to meet their obligations under MARAM and the information sharing schemes.

The Council for Homeless Persons (CHP) has created role specific MARAM alignment practice guidance for homelessness services. Guidance for executives focuses on the broad objectives and cultural change that MARAM aims to achieve. Management guidance provides a tailored checklist of relevant organisational policies and procedures that may require review and adaptation, as well as advice about workforce training. Practitioner guidance aims to further develop practitioner understanding of how the information sharing schemes can benefit clients, as well as links to relevant general MARAM resources.

Work is being undertaken to incorporate MARAM tools into Homelessness IT systems, including the Specialist Homelessness Information Platform (SHIP), Secure Residential Services, The Salvation Army Service and the Mission Information System databases.

DHHS – MCH services

DHHS developed MARAM practice guidance that outlines MCH practitioners’ MARAM responsibilities, and the data collection approach for the MCH workforce. The MARAM practice guidance was circulated to all MCH practitioners by the Municipal Association of Victoria (MAV) in early 2020. DHHS will continue to work with MAV to communicate with and support MCH practitioners with MARAM practice.

MAV has created the MARAM Information Sharing Advisory Group (Advisory Group), comprising MCH and family services coordinators and managers. MAV provides advocacy and support to MCH services and councils to improve capacity and confidence in implementing MARAM.

MAV has released a resource package to support MCH services align with MARAM. The package includes:

- Child Information Sharing and Family Violence Information Sharing Toolkit for Maternal and Child Health Services

- correspondence templates for making a request, proactively sharing, responding to a request, or updating a responder

- documentation of how council policies, procedures and guidelines are expected align to MARAM.

Work is underway to align the Child Development Information System (CDIS), which is used by MCH practitioners to record child health data, with MARAM. The CDIS is anticipated to be fully aligned with MARAM by October 2020. Alignment will enable MCH practitioners to record family violence information, including whether it was requested, received, or proactively shared.

Phase 2 preparations

Work has commenced on preparing hospitals for prescription in Phase 2.

The Strengthening Hospital Responses to Family Violence (SHRFV) team, established in 2014 and led by the Royal Women’s Hospital and Bendigo Health, aims to support best practice responses to family violence in health care settings. Based on the experience of implementing the SHRFV model across Victorian hospitals, a range of resources and tools were developed to support Victorian public hospitals to implement the SHRFV model. This suite of materials also includes specialised content and is known as the SHRFV tool kit.

The SHRFV toolkit was developed prior to the development of the MARAM Framework and Practice Guides, and therefore there is a need to align the toolkit with MARAM in order to support hospitals. Ahead of the commencement of Phase 2, the Royal Women’s Hospital and Bendigo Health received funding from FSV to align the toolkit to MARAM.

In May 2020, SHRFV published MARAM alignment for hospitals and health services. This document provides guidance and advice to hospitals and health services, including designated Mental Health, to develop their MARAM Action Plan. The MARAM Action Plan should demonstrate how the four MARAM pillars will be incorporated into existing policies, procedures and practice. Seven supporting resources accompany the MARAM alignment for hospitals and health services as follows:

- Supporting resource A: Workforce mapping for MARAM Alignment outlines how to map the workforce to the 10 MARAM responsibilities

- Supporting resource B: MARAM consultation questions to inform the development of the MARAM Action Plan

- Supporting resource C: Resource audit tool to assist the audit of existing policies, procedures etc. to ensure MARAM alignment

- Supporting resource D: Organisation audit tool to assist the audit organisational structures and systems against the alignment requirements of MARAM

- Supporting resource E: Facilitating collaborative practice provides guidance on establishing or strengthening partnerships

- Supporting resource F: MARAM Alignment Action Plan template

- Supporting resource G: Briefing paper provides an example briefing paper for leaders that can accompany the final MARAM alignment action plan and workforce mapping

Portfolio examples – collaborative practice

FSV – The Orange Door

As an entry point into the family violence system, The Orange Door receives information from Victoria Police through L17s (now FVRs). The Orange Door staff take steps to assess family violence risk and coordinate a multiagency service delivery to manage immediate risk.

Case study: The Orange Door, Victoria Police, CIP, Community Health Services

The Orange Door received two L17s in respect of Julie (74 years) and her son, Paul (53 years), who were residing together. Paul was identified as experiencing mental health issues and harmful use of alcohol. Julie had previously obtained an intervention order against Paul, but he had since returned to live with her.

When The Orange Door contacted Julie following the latest incident, Paul answered the phone and Julie declined a need for assistance. A risk was identified that Julie may be prevented from accessing help.

The Orange Door completed a CIP request which provided a long history of criminal offending by Paul, multiple periods in prison, significant mental health concerns and serious family violence offending. A consultation occurred with the Advanced Family Violence Practice Leader who recommended a request for health information. This identified Julie had regular engagement with a health service. The Orange Door contacted the health service who were then able to facilitate a discussion with Julie in a safe location. This provided an opportunity for Julie to receive the support she needed.

DJCS – Corrections and Justice

Many organisations have used MARAM to:

- identify gaps in risk assessment information

- make decisions about requests and voluntary information sharing with other services

- undertake needs assessments, develop safety plans for clients and refer them to other services

- establish collaborative practices with family violence specialist services, generalist services, Victoria Police and community organisations.

An example of how organisations in the Corrections and Justice portfolio are collaborating in practice is demonstrated in the following case study:

Case study: DJCS, DHHS

An Aboriginal man was released on parole. His offence was related to family violence against his partner. He had a history of drug use. A family violence intervention order was in force and there was DHHS Child Protection involvement with his children.

The man is participating in ReConnect provided by the Australian Community Support Organisation (ACSO). ReConnect provides targeted, intensive (up to 12 months) post-release reintegration outreach support for prisoners assessed as having high-level transitional needs.

ACSO Reconnect is working collaboratively with the man’s Aboriginal Justice Worker, relevant AOD treatment service and his CCS practitioner to ensure wraparound services are available to him.

This keeps the person using family violence in view, and, where required for risk assessment and management, information will be shared to keep the victim survivor safe.

DJCS – Youth Justice

Key activities that were reported by funded organisations include:

- involvement in sector communities of practice, The Orange Door presentations or other forums, either family violence practice specific or generalist

- seeking specialist advice from family violence services or community-based Child Protection practitioners

- development of organisational memorandum of understandings (MOUs), information sharing flow charts and other resources to ensure staff are confident and clear in their capacity to share information and work collaboratively

- nominating organisational MARAM champions to provide extra support to operational staff to identify relevant family violence risk information within the context of their day-to-day work.

Case study: DJCS, Child Protection, Victoria Police, FSV

A regional Youth Justice Community Support Service provider outlined a case where the organisation worked with Youth Justice, Child Protection, Victoria Police, Corrections Victoria, family violence services and other services to support a young person to engage safety planning, make a report to police and successfully leave a violent relationship.

The provider reflected that the collaborative work of the care team over an extended period was able to keep the young person safe and keep them engaged with services until they were ready to formally pursue charges and leave the relationship.

DJCS – Consumer Affairs Victoria

All FCP organisations participate in regular collaborative practice with other programs internally, and with family violence and other services externally. Collaborative working models have been impacted in 2020 by COVID-19 and remote working.

Examples of enhanced collaborative practice in the last 12 months include:

- worker co-located at local family violence service one day a week

- greater identification of family violence has led to more secondary consultations with in-house family violence programs

- workers are now asking for details of risk assessments when receiving family violence referrals so that the client does not have to retell their story

- workers are providing details from their risk assessments when referring clients to other services so that there is a clearer picture of risk

- workers have access to existing safety planning so can focus resources on resolving the client’s financial issues, whilst maintaining ongoing risk assessment and reviews of safety planning.

Case Study – DJCS

A mother was referred to a financial counsellor by a family violence worker. The mother had left an abusive relationship but had incurred telephone and utility debts. The financial counsellor was able to manage these debts through waivers and payment plans. An insurance company had breached the mother’s privacy, which potentially threatened her safety, and a compensation claim was negotiated. A Flexible Support Package for furniture and a laptop for her daughter’s schooling was applied for from the regional specialist family violence agency. The financial counsellor worked collaboratively with the family violence case worker to ensure client’s safety planning was in place and the client’s relocation was supported.

DJCS – Victim services, support and reform

The introduction of MARAM, and the resulting uplift in the identification of relevant family violence risk information has seen an increase in information sharing and collaboration across all the Victim Assistance Programs (VAPs).

Staff at Cohealth report being more aware of how to determine the predominant aggressor in the context of family violence. They are working more closely with family violence counselling and case management teams and have improved processes through co-case management to deliver better continuity of care for women with high or complex needs who are family violence victim survivors.

The VAP team at Eastern Access Community Health (EACH) have reported developing more supportive and collaborative working relationships with the EACH family violence counselling team, the EACH family violence specialist advisor and the regional specialty services for family violence.

Anglicare Victoria has strong working relationships with specialist family violence services, The Orange Door, Child FIRST, headspace, out of home care, family violence financial counsellors, and gamblers help therapeutic counsellors. Due to these established relationships, information is being shared under existing processes rather than under the CISS or FVISS. Anglicare Victoria has reviewed all MOUs (or service agreements) with external stakeholders to ensure the MARAM principles are included.

Windemere noted an increase in information sharing under FVISS and CISS and increased collaboration across program areas within Windermere, including more secondary consultations.

Case study – DJCS, Victoria Police, FSV

A man presented to a VAP office as a victim of family violence, claiming he had a previous intervention order against his female ex-partner. The man then disclosed that the same ex-partner had recently taken an IVO out against him and had been in contact with a local family violence service. Information provided to the VAP by the Victims of Crime Helpline listed the man as a victim survivor on three L17 referrals, but a different ex-partner was listed as the perpetrator. The VAP suspected the man may have been the predominant aggressor to both ex-partners. The VAP made an information sharing request to the local family violence service for any information pertaining to the man and his two ex-partners to assess risk.

The family violence service had a history of one ex-partner as a victim survivor and the man as a perpetrator over two years. The service shared knowledge that the man was currently continuing to perpetrate family violence against his ex-partner, which they determined using the MARAM Comprehensive Risk Assessment Tool. The family violence service disclosed that they were supporting her to manage the risk and her safety through case management and brokerage for security expenses.

The man was informed that the VAP could not provide support, and he was instead was referred to his local community legal service for court support and to his GP for counselling.

DHHS – Mental Health, Alcohol and other Drugs and Homelessness

VAADA has partnered with NTV and the Council to Homeless Persons to create an online, animated case study that demonstrates best practice information sharing across sectors and how to manage family violence.

The animation demonstrates that different workforces have different considerations when sharing information, what these might be, and how they interact with the considerations and expectations that may exist in other workforces. It also shows the benefits to the client when information is shared.

VAADA is supporting government in developing tools specifically for AOD services that are aligned with MARAM. The tools are expected to be made available to all AOD services through VAADA and to other non-AOD workforces in a generic format.

Portfolio examples – information sharing

The importance of information sharing is reflected in MARAM responsibility 6. Information sharing between services was identified by the Royal Commission as essential for keeping a victim survivor safe and a perpetrator in view and accountable as part of collaborative practice.

The figure below highlights examples of information sharing taking place.[16]

FSV, DHHS and DJCS – the Central Information Point (CIP)

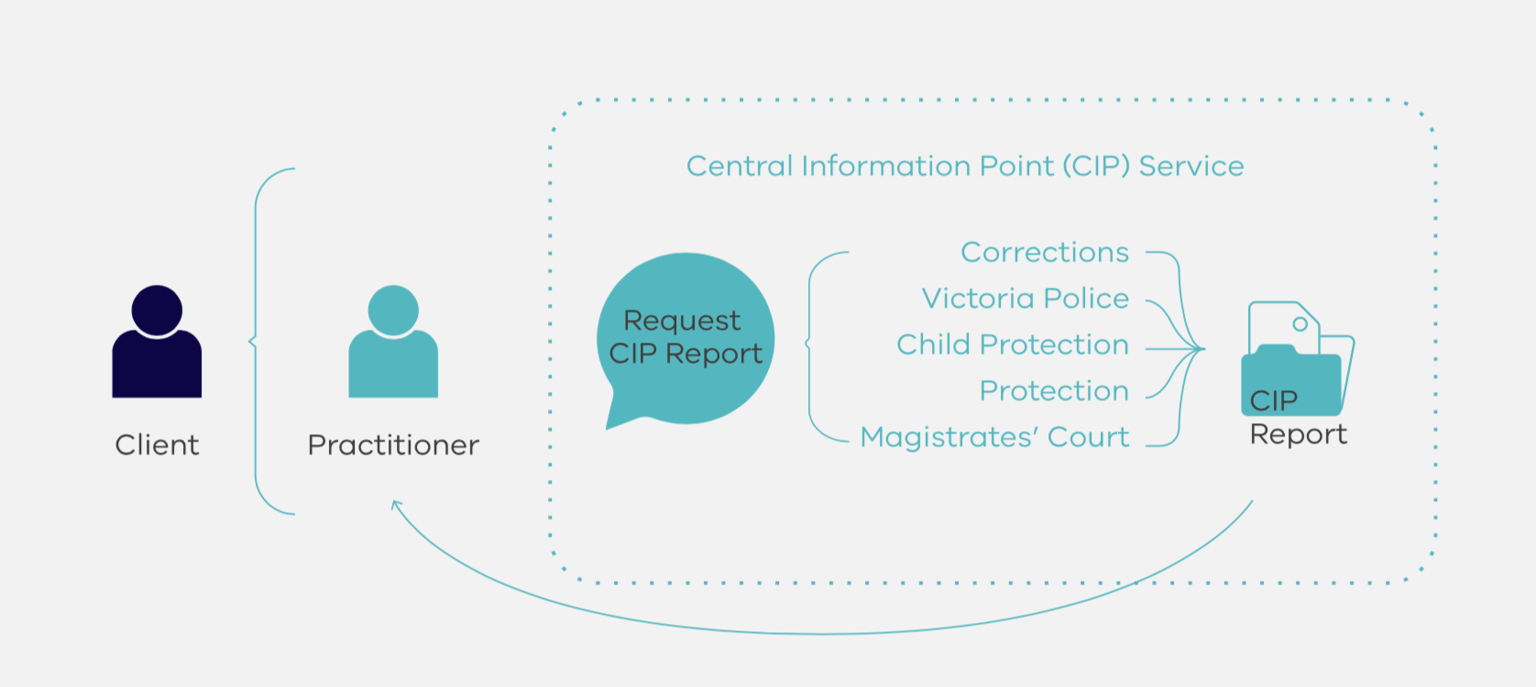

The CIP is a unique and targeted model of multiagency information sharing about perpetrators to inform risk assessment and management. CIP aligns with MARAM responsibility 6 (contribute to information sharing), responsibility 9 (contribute to coordinated risk management) and responsibility 10 (collaborate for ongoing risk assessment and risk management).

CIP brings together perpetrator information from Victoria Police, Courts MCV, Corrections Victoria and DHHS – specifically Child Protection.

The CIP reports continue to provide family violence practitioners with timely access to critical consolidated information to assess and manage risk posed by alleged perpetrators or perpetrators of family violence. CIP reports are currently available to The Orange Door and Berry Street.

CIP staff have attended tailored MARAM training which has helped to further develop their understanding and assessment of family violence risk factors in the data they review and share. On 27 March 2020, the CIP team relocated to work from home. As a CIP report is a collaborative process of pulling together the four data sets to indicate the level of risk from a perpetrator’s patterns of behaviour, systems have been modified to ensure that CIP staff can continue to work collaboratively to effectively share information complete the CIP report. This transition has meant that frontline practitioners continue to be supported to assess and manage risk of family violence.

In 2020–21, FSV has planned actions to support the ongoing implementation and alignment of the CIP to MARAM, including:

- aligning the CIP request form to MARAM risk factors

- enhancing collaborative risk assessment and management practice through system integration and enhancement, policy development and operational support.

CIP case study 1 – FSV, Child Protection

‘The victim survivor told me a few things that raised some flags for me and so I requested a CIP report. It was unbelievable what came back. Not only did he have a whole lot of prior offending, five years back, Child Protection made a case note when one of his kids from a previous relationship described, “Daddy having his hands around Mummy’s neck and hurting her”. Charges were never laid. But it was enough for us to know that he could be extremely dangerous – her life could be in imminent risk.”

CIP case study 2 – Victoria Police, Child Protection, FSV

‘A practitioner spoke of working with a client with limited English whom she identified as a victim survivor of family violence. The client had recently moved from one part of Victoria to another. She was originally identified by the new local police as a perpetrator of child abuse after her partner alleged that she had injured their child. The police and Child Protection excluded the client from the home. The practitioner requested a CIP report on the client’s partner. The CIP report showed that the client’s partner had been identified as a perpetrator of family violence by previous local police with multiple charges that dated back as far as seven years. The practitioner was able to use the information in the CIP report to confirm with police and Child Protection that her client was a victim survivor of family violence, including systematic abuse.’

FSV - RAMPs

RAMPs were an early example of multi-agency risk assessment, risk management and information sharing. The work of RAMP in this area informed the development of MARAM.

Since the introduction of MARAM and the information sharing reforms, I have seen a steady increase in the number of referrals to RAMP originating outside of the traditional referral sources of Victoria Police and specialist family violence services. This includes from services such as Mental Health, Alcohol and other Drugs and a range of other services. I attribute this increase to the introduction of MARAM and the information sharing schemes helping non-specialist family violence services identify and understand family violence risk’ (RAMP Statewide Coordinator).

The continued roll out of MARAM and further implementation of the information sharing schemes is intended to assist early identification of serious risk family violence offenders so that referrals to RAMP may continue to increase over time. In response to this, referrals to RAMP are now not solely based on the identification of a victim survivor’s risk but also the identification of perpetrators who are assessed as a serious threat to the safety of family members.

Ramp case study – DHHS, Victoria Police, FSV, Child Protection

An AOD worker carried out an intake assessment (aligned with MARAM) of a man in his early 20s. Several family violence serious risk factors were identified, including threats to harm his girlfriend, blaming her for his current life situation, including his current homelessness, police family violence assault charges and depression. He threatened to kill her then kill himself and spoke in detail about how he would achieve this.

The AOD worker attempted to contact the girlfriend, however the number the man provided was incorrect. The AOD worker then contacted the local police FVIU for advice on the case. As a result, police interviewed the perpetrator and contacted the local family violence RAMP coordinator to discuss the possibility of calling an emergency RAMP meeting, as they were unable to locate the victim survivor and were concerned for her safety.

The girlfriend was a previous client of a family violence service. Based on previous MARAM assessment from the family violence service and information provided by the AOD service on the current behaviour of the identified perpetrator, the RAMP coordinator called an emergency RAMP meeting.

At the emergency meeting Child Protection were able to provide current contact details for the victim survivor and a risk management action plan was implemented to address the immediate safety concerns.

FSV – CASA Forum

In the April 2020 information sharing survey undertaken by CASA Forum, when asked whether ‘Information sharing reforms have led to improved outcomes for victim survivors’, 75 per cent of respondents stated yes.

Respondents commented that the Information Sharing Schemes provide ‘consistent processes’, ‘greater collaboration’, ‘shared understanding of assessing risk and risk management’, and that services are ‘more willing to share information’.

One respondent commented, ‘Information sharing has allowed staff to see the benefits to clients both therapeutically and in accessing support and this has changed their view’. The increase in information sharing is evident:

- between September 2018 and May 2019 – 25 information sharing records

- between June 2019 and September 2019 – 330 information sharing records

- between December 2019 and February 2020 – 360 information sharing records.

DJCS - Corrections and Justice Service

A total of 1,599 requests for information have been received by Corrections Victoria since FVISS was implemented, including requests made to the Adult Parole Board. During the 2019–20, financial year Corrections Victoria received 1,080 requests and shared information a total of 1,051 times.

An information sharing factsheet is available for all Corrections Victoria staff outlining the types of information that can be shared under relevant legislation, who the information can be shared with and in what situations. This is in addition to nine one-pager family violence information sheets, developed by DJCS that detail what information key business areas can share, what information they have and what information is commonly beneficial to each business unit.

DJCS – Justice Health

Justice Health has clear protocols for information sharing under both the FVISS and CISS. These practices are embedded into ongoing business operations. Justice Health has a dedicated Assessment and Support Officer who oversees the release of information under the FVISS and CISS and liaises with other ISEs.

A review of information-sharing practices under both FVISS and CISS has been undertaken to ensure procedures are operating effectively and efficiently, and that any roadblocks are addressed to ensure the smooth and timely sharing of risk relevant information. A feedback process has been established with requestors of information under the FVISS and CISS; feedback to date has been limited but positive.

In the 2019–20 financial year, Justice Health received a total of 44 requests for information; 27 of these under the FVISS, four under the CISS, and 13 under both schemes. Justice Health declined one request as the requestor was not an authorised ISE. A further 17 requests were redirected to other agencies.

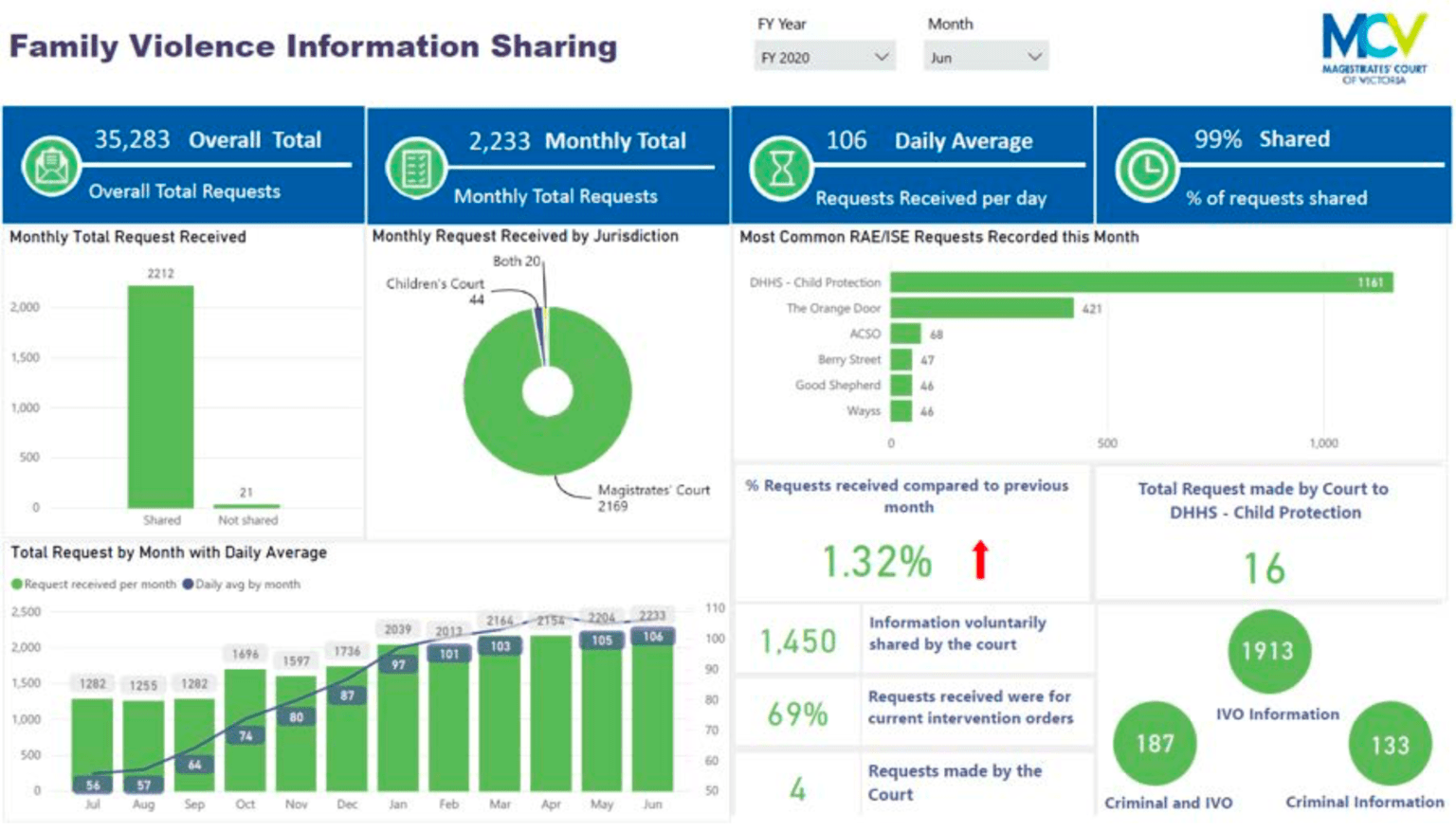

The courts

The courts continue to receive monthly record-breaking requests and have not yet experienced a plateau in the number of requests received. To manage the high volume of requests and improve efficiency, the courts have put in place improvements in the FVISS data storage and reporting process.

Case study – DHHS and the courts

DHHS Child Protection made a request under FVISS for a copy of an intervention order to support a family violence risk assessment. The courts’ central information sharing team advised the current order had not been served on the respondent. Upon further investigation, DHHS established that the respondent had been served with an older intervention order (IVO) but not the current IVO. The central information sharing team then contacted the relevant Magistrates’ Court registry and provided them with the updated respondent information to enable the respondent to be served with the new order with the new date. The current address for the respondent was requested from DHHS Child Protection. The respondent was subsequently served with the current intervention order at the address provided by DHHS. The victim survivor now had the correct protection, and the respondent was served with the current intervention order.

Assessment of MARAM progress

As identified above, the complexity of the reforms and the change management required to drive consistent and collaborative practice is reliant on a set of centralised tools and resources which are then tailored by departments, sector peaks and organisations to suit workforces.

The MARAM reforms have involved a strongly consultative approach across government and expert groups in the development of resources, including the supporting practice guidance.

As can be seen in the examples provided of MARAM alignment, there continues to be a significant focus on the preparation of resources and updating of policies, procedures, practice guidance and tools and ensuring these are suitably tailored to workforces. These steps are essential to support building a shared understanding as well with organisational leadership as to what MARAM alignment means for the particular organisation and workforce/s. Additionally, alignment is likely to benefit from the authorising environment being extended from legislation only into more direct links with organisations via departments.

‘The embedment of MARAM responsibilities into legislation has provided an authorising environment, however, stronger links are required between funding and service agreements and evaluation’ (Statewide Family Violence Integration Advisor Committee Member).

One of the objectives of the MARAM Framework is to provide guidance on how to align to ensure consistent service delivery. The examples in this chapter illustrate that in the past year significant steps have been taken across portfolios to develop the foundational resources required to achieve this outcome. The case studies demonstrate early successes of the MARAM reforms in creating a consistent and collaborative practice.

Future assessment of progress will be measured via increased information sharing, increased reporting from use of online TRAM, and where MARAM tools are embedded (such as within SHIP) and completion of Monitoring and Evaluation Framework Annual Organisational Survey.

[15] Noting this is six days after the reporting period.

[16] Noting that there is no legal requirement for portfolios to specifically report on numbers of information shares taken place beyond what is already within the capability of systems. An absence of information sharing numbers for a department, portfolio or organisation does not indicate information sharing does not take place.

Updated