- Date:

- 20 Feb 2020

Message from the Minister

Message from the Minister

The Victorian Government’s commitment to implement all 227 recommendations of the Victorian Royal Commission into Family Violence (the Royal Commission) marked a turning point in the response to family violence. The intent is clear: family violence will not be tolerated, and all services will work together to build a future where all Victorians live free from family violence, and where women and men are treated equally and respectfully.

As the Minister for Prevention of Family Violence, I am responsible for preparing an annual report on the government’s implementation of the Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management Framework (MARAM) — the approved family violence and risk assessment and management framework.

MARAM commenced in September 2018. This report covers the period from September 2018 to 30 June 2019.

All ministers with framework organisations within their portfolios have reported to me on the work being undertaken to align to MARAM. This report is consolidated from my portfolio report and the reports provided by:

- The Hon. Ben Carroll MLA, Minister for Crime Prevention, Minister for Corrections, Minister for Youth Justice, Minister for Victim Support

- The Hon. Luke Donnellan MLA, Minister for Child Protection

- The Hon. Martin Foley MLA, Minister for Mental Health

- The Hon. Jill Hennessy MLA, Attorney-General

- The Hon. Lisa Neville MLA, Minister for Police and Emergency Services

- The Hon. Marlene Kairouz MLA, Minister for Consumer Affairs, Gaming and Liquor Regulation

- The Hon. Jenny Mikakos MLC, Minister for Health

- The Hon. Richard Wynne MLA, Minister for Housing

There is, of course, much more going on than can be represented in one report. This consolidated report reflects the key areas of progress across departments, organisations and agencies.

Although only the first consolidated annual report on the implementation of MARAM, it is already evident that a significant breadth of work has been undertaken in the first year of operation.

The focus of work in this reporting period has been on laying the foundations for change across services that support Victorians, including Victoria Police, the Magistrates and Children’s Courts, child and family services and specialist family violence providers, among others. Policies and procedures are being put in place to enable the workforces within framework organisations to identify, assess and manage family violence risk.

Further training and resources are being developed to support workforces, with plans underway to continue the capability uplift through specialised training and provision of new services.

It is particularly exciting to see the service system actively engaging in collaborative practice — the need for an integrated service system being a primary need identified by the Royal Commission and identified in the MARAM Framework itself. Collaboration is taking place at all levels, from departments to individual professionals. Across the affected sectors communities of practice are promoting consistent and collaborative ways of working to ensure the entire system is contributing to keeping victim survivors safe and holding perpetrators accountable.

As we look to the future and the second year of implementation of these reforms, it is important to recognise that the work is not yet done. Alignment to MARAM requires a significant cultural change and development of a shared and sophisticated understanding of family violence, as well as practical application of the reforms through assessment and management of family violence risk. With 35,000 workers prescribed in this first phase of MARAM and a further potential 350,000 to follow in September 2020, all workforces, organisations and departments will need to continue to consider, refine and mature their approaches to enable an effective family violence system until the reforms are fully embedded.

Hon Gabrielle Williams MP

Minister for Prevention of Family Violence

Minister for Women

Minister for Youth

Summary of the reforms

Summary of the Reforms

Recommendation 1 of the Royal Commission was to deliver a ‘comprehensive framework that sets minimum standards and roles and responsibilities for screening, risk assessment, risk management, information sharing and referral throughout Victorian agencies’ (Royal Commission into Family Violence:(opens in a new window) report and recommendations).

The framework was recommended to include:

- weighted risk factors to identify risk as low, medium or high

- evidence-based risk indicators that are specific to children

- comprehensive practice guidance

- consideration of the needs of the diverse range of victim survivors and perpetrators

The Royal Commission specifically considered the appropriate operating mechanism to ensure departments, agencies and organisations could be supported in aligning to the redeveloped framework. It concluded that primary legislation should be used to set out relevant family violence principles, and the use and purpose of a framework. The content and detail of the framework could then be approved by the relevant minister or ministers through Regulations, providing flexibility to amend content if changes in practice emerged and to prescribe organisations. (Royal Commission into Family Violence(opens in a new window): report and recommendations final report).

The MARAM Framework delivers on this recommendation. The MARAM Framework commenced in law from September 2018 and is the approved family violence risk assessment and management framework under the Family Violence Protection Act 2008(opens in a new window) (FVPA).

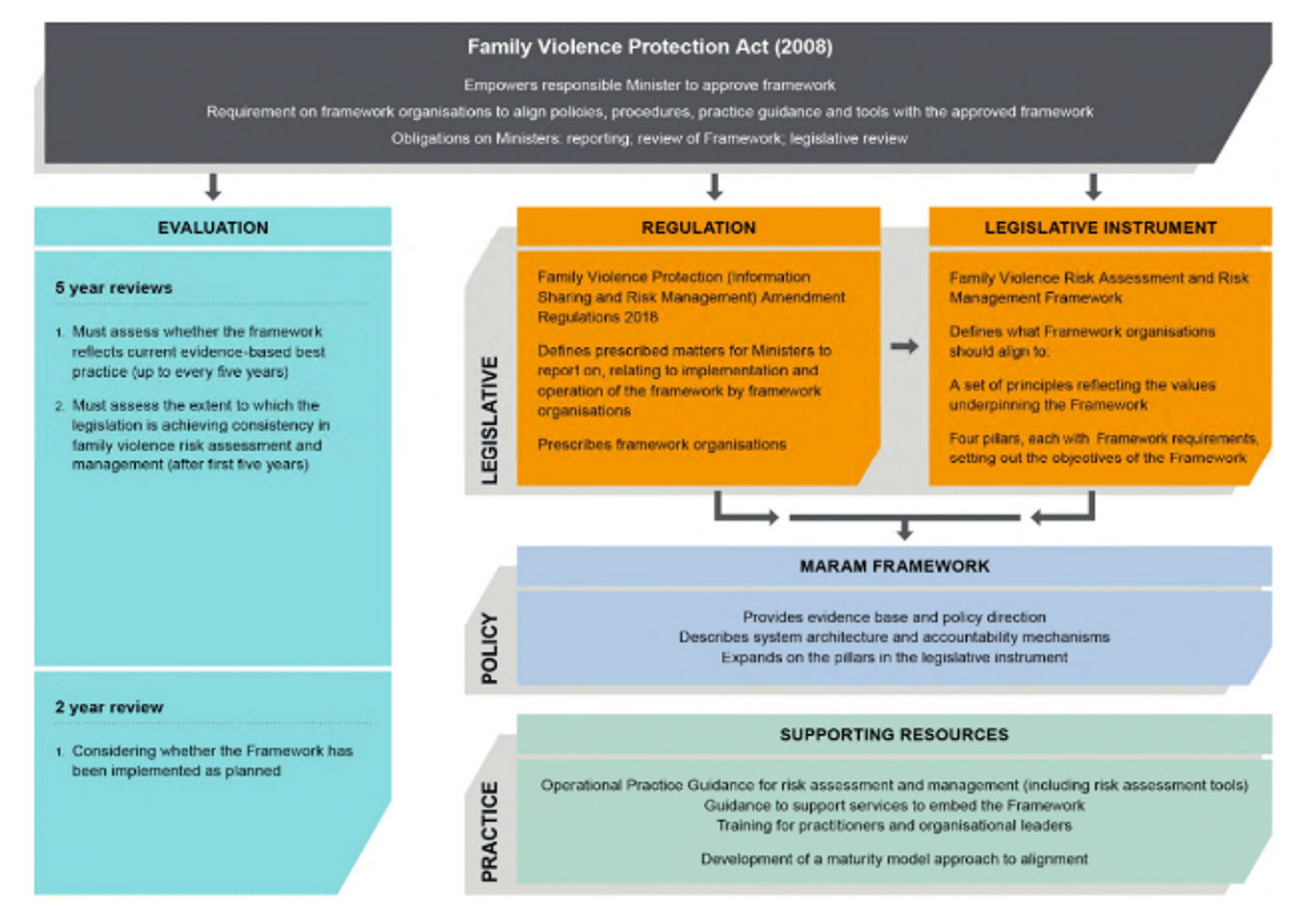

Figure 1 provides a summary of the legislative and regulatory environment created by MARAM.

The Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme (FVIS Scheme), a key enabler of MARAM, commenced in February 2018. The FVIS Scheme enables organisations and services prescribed as Information Sharing Entities (ISEs) to share information related to assessing or managing family violence risk. The FVIS Scheme supports ISEs to keep perpetrators in view and accountable, and to promote the safety of victim survivors of family violence.

Concurrent with the commencement of MARAM, the Child Information Sharing Scheme (CIS Scheme) also commenced, covering a similar group of workforces. The CIS Scheme allows prescribed organisations and professionals who work with children, young people and their families to share information with each other to promote children's wellbeing and safety. Family violence and child wellbeing concerns often co-occur, and in practice, professionals are likely to consider using either or both schemes in combination as appropriate.

As a consequence, resources, training and governance groups have maintained a focus on all three reforms.

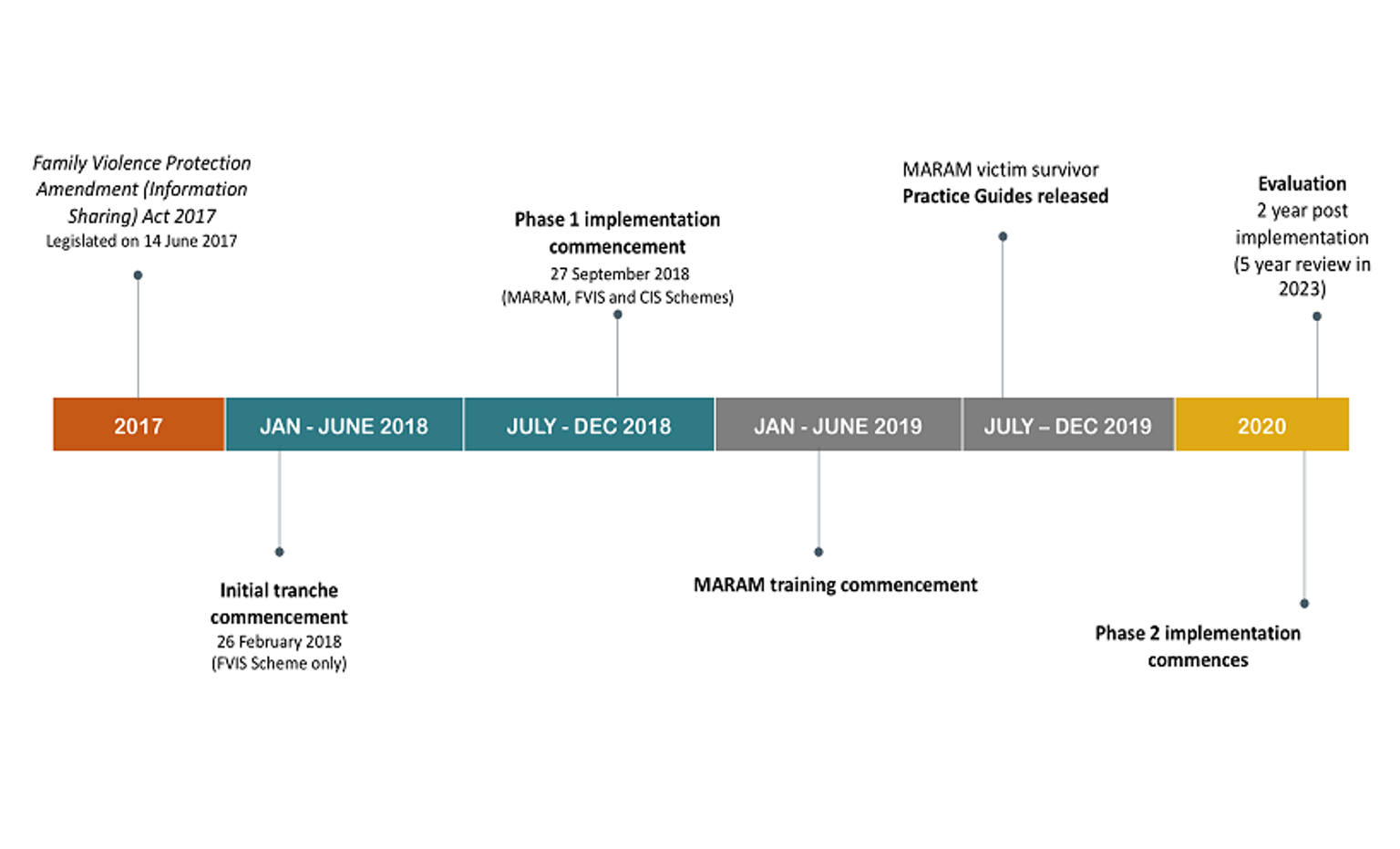

Figure 2 illustrates a broad overview of the timeline of the reforms from commencement, along with key milestones.

In September 2018, Phase 1 prescribed more than 855 organisations with more than 35,000 professionals to align with MARAM. These framework organisations include the specialist family violence sector and services in housing, mental health, alcohol and other drugs, police, courts, justice and corrections. Appendix 1 sets out a comprehensive list of all organisations prescribed in Phase 1 across all three reforms.

Work is currently underway to prescribe a second phase of framework organisations from late 2020. Subject to stakeholder consultation and government decisions, it is expected Phase 2 will focus on universal services including in health and education (noting 'Universal service systems that are available to all community members are ideally placed to play a much greater role in identifying family violence at the earliest possible stage.’ Source: RCFV: summary and recommendations, p. 9).

It is anticipated Phase 2 will bring in more than 350,000 extra professionals from an estimated 8,000 organisations. Appendix 2 sets out the proposed list of Phase 2 workforces, which, at the time of preparation of this report, is subject to ministerial approval.

The MARAM Framework

The MARAM Framework contents

The MARAM Framework outlines 10 principles that underpin the reforms. The principles support four pillars against which prescribed organisations are required to align their policies, procedures, practice guidance and tools. The pillars include 10 responsibilities for identifying, assessing and managing family violence risk across service sectors.

MARAM principles

The principles are aimed at providing professionals and services with a shared understanding of family violence, and facilitating consistent, effective and safe responses for people experiencing family violence. The principles are:

- family violence involves a spectrum of seriousness of risk and presentations, and is unacceptable in any form, across any community or culture

- professionals should work collaboratively to provide coordinated and effective risk assessment and management responses, including early intervention when family violence first occurs to avoid escalation into crisis and additional harm

- professionals should be aware, in their risk assessment and management practice, of the drivers of family violence, predominantly gender inequality, which also intersect with other forms of structural inequality and discrimination

- the agency, dignity and intrinsic empowerment of victim survivors must be respected by partnering with them as active decision-making participants in risk assessment and management, including being supported to access and participate in justice processes that enable fair and just outcomes

- family violence may have serious impacts on the current and future physical, spiritual, psychological, developmental and emotional safety and wellbeing of children, who are directly or indirectly exposed to its effects, and should be recognised as victim survivors in their own right

- services provided to child victim survivors should acknowledge their unique experiences, vulnerabilities and needs, including the effects of trauma and cumulative harm arising from family violence

- services and responses provided to people from Aboriginal communities should be culturally responsive and safe, recognising Aboriginal understanding of family violence and rights to self-determination and self-management, and take account of their experiences of colonisation, systemic violence and discrimination and recognise the ongoing and present day impacts of historical events, policies and practices

- services and responses provided to diverse communities and older people should be accessible, culturally responsive and safe, client centred, inclusive and non-discriminatory

- perpetrators should be encouraged to acknowledge and take responsibility to end their violent, controlling and coercive behaviour, and service responses to perpetrators should be collaborative and coordinated through a system-wide approach that collectively and systematically creates opportunities for perpetrator accountability

- family violence used by adolescents is a distinct form of family violence and requires a different response to family violence used by adults, because of their age and the possibility that they are also victim survivors of family violence

MARAM pillars

The MARAM Framework is structured around four conceptual pillars against which leaders of organisations must align policies, procedures, practice guidelines and tools. Each pillar has its own objective and requirement for alignment.

Pillar 1: Shared understanding of family violence

It is important that all professionals, regardless of their role, have a shared understanding of family violence and perpetrator behaviour, including its drivers, presentation, prevalence and impacts. This enables a more consistent approach to risk assessment and management across the service system and helps keep perpetrators in view and accountable and victim survivors safe. To that end, Pillar 1 aims to build a shared understanding about:

- what constitutes family violence, including common perpetrator actions and behaviours, and patterns of coercion and control

- the causes of family violence, particularly community attitudes about gender, and other forms of inequality and discrimination

- established evidence-based risk factors, particularly those that relate to increased likelihood and severity of family violence

Pillar 2: Consistent and collaborative practice

Pillar 2 builds on the shared understanding of family violence created in Pillar 1, by developing consistent and collaborative practice for family violence risk assessment and management across different professional roles and sectors.

Each professional should use the Structured Professional Judgement approach, appropriate to their role in the system, to assess the level or ‘seriousness’ of risk, informed by:

- the victim survivor’s self-assessed level of risk

- evidence-based risk factors (using the relevant assessment tool)

- information sharing with other professionals as appropriate to help inform professional judgement and decision making

- using an intersectional analysis when applying professional judgement to determine the level of risk

Pillar 3: Responsibilities for risk assessment and management

Pillar 3 builds on Pillars 1 and 2 and describes responsibilities for facilitating family violence risk assessment and management. It provides advice on how professionals and organisations define their responsibilities to support consistency of practice across the service system, and to clarify the expectations of different organisations, professionals and service users.

Pillar 4: Systems, outcomes and continuous improvement

Pillar 4 outlines how organisational leaders and governance bodies contribute to, and engage with, system-wide data collection, monitoring and evaluation of tools, processes and implementation of the Framework. This pillar also describes how aggregated data will support better understanding of service-user outcomes and systemic practice issues and, in turn, continuous practice improvement. This information will also inform the five-year evaluation to ensure it continues to reflect evidence-based best practice.

MARAM responsibilities

Pillar 3 of the MARAM Framework provides a structure of 10 responsibilities of practice for professionals and services working in organisations and sectors across the family violence system.

All organisational leaders in prescribed framework organisations are required to have an understanding of the roles and responsibilities of professionals and services within their organisation. Identifying and mapping these roles within and across the organisation will support shared understanding of the roles and responsibilities of professionals and services across the service system. This will assist professionals and services to understand how they can work together to identify, assess and manage family violence risk, through information sharing, secondary consultation and referral.

Responsibility 1: Respectful, sensitive and safe engagement

Ensure staff understand the nature and dynamics of family violence, facilitate an appropriate, accessible, culturally responsive environment for safe disclosure of information by service users, and respond to disclosures sensitively. Ensure staff know they must engage safely with a service user who may be a perpetrator, and not to collude with or respond to coercive behaviours.

Responsibility 2: Identification of family violence

Ensure staff use information gained through engagement with service users and other providers (and in some cases through the use of screening tools to aid identification or routine screening of all clients) to identify indicators of family violence risk and potentially affected family members. Ensure staff understand when it might be safe to ask questions of clients who may be a perpetrator, to assist with identification.

Responsibility 3: Intermediate risk assessment

Ensure staff can competently and confidently conduct intermediate risk assessment of adult and child victim survivors using the Structured Professional Judgement Approach and appropriate tools, including the Brief and Intermediate Assessment tools. Where appropriate to the role and mandate of the organisation or service, and when safe to do so, ensure staff can competently and confidently contribute to behaviour assessment through engagement with a perpetrator, including through use of the Perpetrator Behaviour Assessment Tool, and contribute to keeping them in view and accountable for their actions and behaviours.

Responsibility 4: Intermediate risk management

Ensure staff actively address immediate risk and safety concerns relating to adult and child victim survivors, and undertake intermediate risk management, including safety planning. Those working directly with perpetrators should attempt intermediate risk management when safe to do so, including safety planning.

Responsibility 5: Seek consultation for comprehensive risk assessment, risk management and referrals

Ensure staff seek internal supervision and further consult with family violence specialists to collaborate on risk assessment and risk management for adult and child victim survivors and perpetrators, and make active referrals for comprehensive specialist responses, if appropriate.

Responsibility 6: Contribute to information sharing with other services (as authorised by legislation)

Ensure staff proactively share information relevant to the assessment and management of family violence risk and respond to requests to share information from other information sharing entities under the FVIS Scheme, privacy law or other legislative authorisation.

Responsibility 7: Comprehensive assessment

Ensure staff in specialist family violence positions are trained to comprehensively assess the risks, needs and protective factors for adult and children victim survivors. Ensure staff who specialise in working with perpetrators are trained and equipped to undertake comprehensive risk and needs assessment to determine the seriousness of the perpetrator’s risk and provide tailored intervention and support options, and to contribute to keeping them in view and accountable for their actions and behaviours. This includes an understanding of situating their own roles and responsibilities in the broader system to enable mutually reinforcing interventions over time.

Responsibility 8: Comprehensive risk management and safety planning

Ensure staff in specialist family violence positions are trained to undertake comprehensive risk management through development, monitoring and actioning of safety plans (including ongoing risk assessment), in partnership with the adult or child victim survivor and support agencies. Ensure staff who specialise in working with perpetrators are trained to undertake comprehensive risk management through development, monitoring and actioning of risk management plans (including information sharing), monitoring across the service system (including justice systems), and actions to hold perpetrators accountable for their actions. This can be through formal and informal system accountability mechanisms that support perpetrators’ personal accountability, to accept responsibility for their actions, and work on the behaviour change process.

Responsibility 9: Contribute to coordinated risk management

Ensure staff contribute to coordinated risk management, as part of integrated, multidisciplinary and multi-agency approaches, including information sharing, referrals, action planning, coordination of responses and collaborative action acquittal.

Responsibility 10: Collaborate for ongoing risk assessment and risk management

Ensure staff are equipped to collaboratively monitor, assess and manage risk over time to identify changes in assessed level of risk and ensure risk management and safety plans respond to changed circumstances, including escalation. Ensure safety plans are enacted.

Language in this report

Language in this report

At its core, family violence is a deeply gendered issue rooted in structural inequalities and an imbalance of power between women and men which is reflected in any gendered language used within this report.

The word family has many different meanings. Within this report, the word family is all encompassing and acknowledges the variety of relationships and structures that can make up a family unit and the range of ways family violence can be experienced, including through family-like or carer relationships as defined in the FVPA.

The term family violence encompasses the wider understanding of the term across all communities, including Aboriginal community understandings of the term.

This report refers to people, including children and young people, who have experienced family violence as victim survivors as guided by members of the Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council, who are people with lived experience of family violence. Not every person who has experienced or is experiencing family violence identifies with this term. Family violence is only one part of a victim survivor’s life and does not define who they are. The term is intended to acknowledge the strength and resilience shown by victim survivors who have experienced or currently live with family violence.

This report uses the term perpetrator to describe people who choose to use family violence, acknowledging the preferred term for Aboriginal people and some communities is a person who uses violence. The term perpetrator is not appropriate when referring to adolescents who use family violence and women who use force in defence.

Throughout this document, the term Aboriginal is used to refer to both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Awareness of diversity within the Victorian population is increasing as people express multiple forms of identity and belonging. Diverse groups frequently contend with intersectional risks when experiencing family violence. Intersectionality describes how characteristics such as gender, ethnicity, ability, sexual orientation, gender identity, religion or age can interact on multiple levels to create forms of power and social inequality. These social categorisations can form systems of oppression or domination resulting in structural inequalities, barriers or discrimination.

Abbreviations in this report

List of government departments and their prescribed program areas (if relevant)

DET - Department of Education

DHHS - Department of Health and Human Services

- housing (delivered by DHHS)

- homelessness services

- child protection

- out of home/secure welfare services (care services)

- child and family services

- designated mental health services

- alcohol and other drug services

- maternal and child health service

DJCS - Department of Justice and Community Safety

- Victoria Police

- Corrections

- Youth Justice

- Koori Justice Unit

- Victim Support

- Consumer Affairs Victoria

Courts

- Attorney-General’s Office

- Magistrates Court of Victoria

- Children’s Court of Victoria

FSV - Family Safety Victoria

- The Orange Door

- central information point

- perpetrator treatment programs

- sexual assault clinics

- family violence specialist practitioners

Abbreviations commonly used in report

- AAG - Aboriginal Advisory Group

- AOD - Alcohol and other drug

- BCYF - Barwon Child Youth and Family

- CALD - Culturally and linguistically diverse

- CAV - Consumer Affairs Victoria

- CCS - Community Correctional Services

- CCV - Children’s Court of Victoria

- CIS Scheme - Child Information Sharing Scheme

- CRAF - Common Risk Assessment Framework (MARAM predecessor)

- DVRCV - Domestic Violence Resource Centre Victoria

- FCP - Financial Counselling Program

- FVIS Scheme - Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme

- FVIU - Family Violence Investigation Unit at Victoria Police

- FVPA - Family Violence Protection Act

- FVR - Family Violence Report used by Victoria Police

- FVRIC - Family Violence Regional Integration Committee

- ISE - Information Sharing Entities

- LGBTIQ - Lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, intersex and queer communities

- MARAM - Multi-agency Risk Assessment and Management

- MCH - Maternal and Child Health

- MCV - Magistrates’ Court of Victoria

Contents of this report

Contents of this report

This report is structured in four sections divided into subsections with a summary of progress made by departments, agencies and framework organisations.

Building the service system

Achieving the vision laid out by the government — to see a Victoria free from violence — requires long-term investment, system-wide organisational and culture change, as well as significant capability development to see MARAM appropriately implemented.

Initiatives undertaken during the first year of operation prioritise activities that will support the macro and micro changes needed within workforces as part of alignment.

This first section examines the foundational activities to build the service system that will support the reforms longer term:

- managing change — change management strategies and alignment plans

- tools for consistent practice — MARAM-aligned tools to enable consistent practice across the service system

- action plans to implement change — plans and frameworks putting into practice the change management strategies

Setting up a capable workforce

Redeveloping the system is a necessary process to ensure better outcomes for Victorians. However, for MARAM to be implemented, the workforce on the ground must be equipped to understand and implement the changes in practice.

This section examines the activities undertaken to create capable workforces to identify, assess and manage family violence risk:

- workforce development: strategies, support and capacity building — details the various activities taking place to raise the capacity of workforces to align to MARAM

- capacity building: an intersectional lens — the work being undertaken to apply Principles 7 and 8 of MARAM

- resources and workforce support — the development of resources designed to support workforces applying responsibilities and aligning to MARAM

- new non-accredited MARAM training — training modules available across the whole-of-government to introduce the MARAM reforms and responsibilities

- accredited training — work being undertaken to ensure accredited training across workforces aligns with MARAM, where those workforces are prescribed or likely to be prescribed as part of the reforms

Collaborative practice

As a core component of the MARAM Framework in Principle 2, Pillar 2 and Responsibilities 5, 6, 9 and 10, this section focuses on the work being done to create collaborative practice between workforces:

- information sharing — looks specifically at the Information Sharing reforms, and the progress and impact of their use

- service system collaboration — explores the work and changes being made on a formal, systems level to promote and enable collaborative practice

- information collaborative practice — summarising the developing relationships between departments, agencies and organisations as alignment to MARAM progresses

Ensuring continuous improvement

This section outlines the evaluation processes being established by departments and how the results of those evaluations will inform future progress of MARAM alignment.

Building the service system to enable a consistent response to family violence

Getting help should not depend on the particular entry point chosen by the victim

All services that come into contact with family violence victims should be equipped to identify, and in some cases, assess and manage risk, and to ensure that victims are supported.

Royal Commission into Family Violence:(opens in a new window) summary and recommendations.

Central to the recommendations of the Royal Commission is the need for a service system that works for victim survivors of family violence. When a victim survivor seeks help, they should receive it, no matter what service they choose to disclose to. And that response should consistently be respectful, sensitive and suitable to the victim survivor’s needs and identities.

The MARAM Framework sets out the procedures and goals for framework organisations to implement in order to create this responsive service system.

In the first year of operation, the focus for departments has been setting up the system foundations to enable a consistent approach to family violence across all services. This work has included:

- change management strategies and positions to coordinate and bring about the change

- creation of frameworks to support implementation of MARAM (such as a focus on intersectionality), including tailored frameworks for specific workforces

- development of high-quality tools of practice that are aligned to MARAM, and which help create a consistent service response

Managing change

It is important for a sustainable future of the reforms that departments, peak bodies and organisations themselves are equipped to manage the change process and embed MARAM so it becomes business as usual.

Change management activities were delivered to further this aim.

Victorian Government change managers

The Victorian Government has funded change management positions in key affected agencies, namely the Department of Justice and Community Safety (DJCS), Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) and the Magistrates’ Court of Victoria (MCV) and the Children’s Court of Victoria (CCV) (collectively identified as the Courts). The positions commenced in 2017–18 and have been funded for three years for $1.8 million a year.

The Victorian Government has also funded a change management position in the Department of Education (DET), which will have prescribed workforces from 2020.

The positions will enable the affected agencies to develop tailored change management strategies and implementation plans to assist framework organisations within their portfolios to align to MARAM; some of these strategies and plans are already developed and underway as described below.

Courts change management plan

The Courts have engaged a change manager to progress a change management plan. Phase 1 of the plan involved the Courts hosting change workshops with internal staff to assess the current and future state of the response to family violence.

Phase 2 of the Courts’ implementation plan will focus on alignment and operational readiness with an emphasis on family violence-related policies, procedures, learning and development and training materials.

DJCS MARAM alignment strategy

DJCS developed the Aligning with the Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management Framework for Better Family Violence Outcomes 2019–2020 Strategy. The Strategy guides key areas of alignment across the range of DJCS agencies and workforces.

The Strategy describes how DJCS will progress its alignment with MARAM over the next two years, and it outlines the focus areas and key initiatives of framework organisations and programs, both within and funded by the department, towards achieving that alignment.

The immediate aim of the Strategy is to provide a pathway for the department to be aligned appropriately with MARAM. The Strategy also aims to make a longer-term contribution to the objectives of the MARAM Framework including that:

- family violence risk assessment and management informs all MARAM-prescribed justice services and programs, to support the safety and recovery of those experiencing family violence

- victim survivor self-assessment of their own safety is understood and integrated into family violence risk assessment and management strategies

- effective information sharing that keeps perpetrators in view is an important way to support consistent family violence risk assessment and management across services and sectors

DJCS also developed the Information Sharing Culture Change Strategy and Action Plan in 2018–2019 to support and build the information-sharing culture necessary to enact responsibilities 5 and 6 of MARAM.

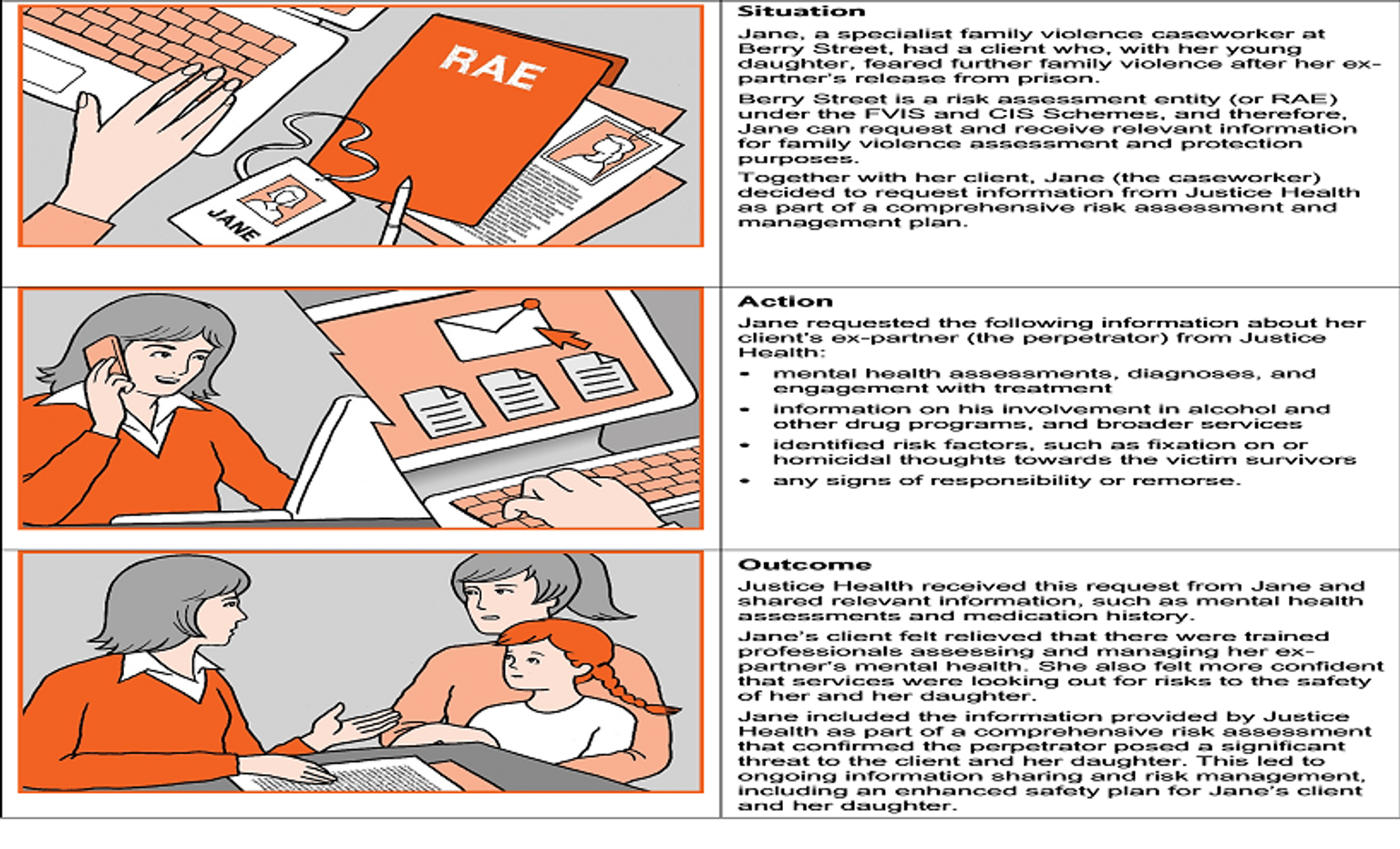

Justice Health

Justice Health actively supported the development and implementation of the DJCS Information Sharing Culture Change Strategy and Action Plan. To help other information sharing entities (ISEs), Justice Health:

- created a short video for DJCS ISEs outlining risk-relevant information that Justice Health may hold

- collaborated with the Berry Street family violence service on their short video showcasing successful information sharing between Justice Health and Berry Street

- prepared a one-page summary outlining the information Justice Health holds

Justice Health is also working with key stakeholders to ensure there is a clear understanding of the changes underway. The range of methods Justice Health has used to communicate with stakeholders includes:

- holding targeted workshops for contracted providers conveying MARAM and information-sharing concepts and obligations

- contributing to DJCS family violence newsletters

- presenting at the Justice Health quarterly staff forum

- developing an operations manual including process flows for information sharing

- providing information about Justice Health’s processes to the DJCS Regional Services Network

Justice Health has identified information technology and data gathering opportunities for MARAM alignment and continuous improvement, including:

- building a new request type into Justice Health’s case management system, which allows for data capture and provides procedural guidance for Justice Health staff when completing requests. The request type is built around the Family violence information sharing ministerial guidelines

- updating Justice Health’s electronic medical record database for adult prisoners to enable health staff to apply family violence flags to relevant case notes for an individual and family violence alerts against an individual’s entire medical record

- collaborating with contracted providers to establish a reporting tool to inform on FVIS and CIS activity across prison health services. This will provide valuable information about the uptake of information sharing practice over time

Future plans for implementation in Justice Health include:

- develop a communications and engagement plan for contracted providers

- develop a touch-point map to determine the roles and responsibilities for Justice Health staff under the MARAM to equip staff with the training, practice tools and support to fulfill their relevant responsibilities under MARAM

- conduct prisoner-journey mapping to identify touch points with people experiencing or using family violence in the prison system and youth custodial centres

Victoria Police Family Violence Response Model

The Family Violence Response Model (FVRM) has been developed to integrate the four pillars of MARAM in its design so that they are mutually supportive and reinforcing. The FVRM set out the change process to embed MARAM into the police family violence response.

The FVRM has four key components:

- development and implementation of Family Violence Investigation Units (FVIUs)

- a new Family Violence Report (known as the L17)

- a Case Prioritisation and Response Model (CPRM) for FVIUs along with targeted training

- a mandatory force-wide education program

DHHS Champions of Change forum

DHHS in partnership with the Centre for Excellence in Child and Family Welfare facilitated the Champions of Change forum in August 2018 to bring together senior practitioners and executives from across DHHS workforces to establish collective goals to prepare for the information sharing reforms. The forum was designed to engage organisational leaders to drive cultural change, and provide an environment that promotes and encourages information sharing and supports collaborative practice.

Further Champions of Change forums are planned for 2020. These forums will provide a platform to discuss the broader service sector’s progress on developing a shared understanding of family violence.

Organisational resources to guide change

All workforces need to be supported in the delivery of MARAM-aligned practice with appropriate resources.

To prepare organisations for the coming changes, FSV developed a range of guidance products and tools to assist organisational leaders in their planning for implementation of MARAM.

- MARAM Framework on a page(opens in a new window) — this document provides a quick reference guide to MARAM. It summarises the principles, pillars, responsibilities, system architecture and accountability, and the legislative and policy environment

- MARAM alignment checklist(opens in a new window) — a checklist to assist organisational leaders identify important first steps in aligning to MARAM. The checklist sets out a series of activities to undertake in the first 12 months of alignment activity

- MARAM responsibilities: decision guide(opens in a new window) — a diagram for organisational leaders to use to determine the appropriate responsibilities for different staff roles within their organisation. The decision guide can be tailored by sector leaders to make it more specific to a particular workforce or sector

FSV is also developing guidance for use by organisational leaders and managers on the change management process to embed MARAM in their business-as-usual operations.

The guidance will not be prescriptive in the processes an organisation must undertake, recognising that the breadth of organisations encompassed by the reforms will not be met by a uniform approach. The guidance will acknowledge the maturity approach identified by the MARAM Framework, and that alignment is progressive, and will require change over time.

As well as practical steps towards aligning to the MARAM on an operational basis, the guidance will examine ways to achieve the deeper cultural change envisaged by the Royal Commission as necessary to see a Victoria free from family violence.

Tools for consistent practice

A further essential element of setting up the service system is the creation of tools and guidance which are MARAM aligned. For a victim survivor, no matter what service they disclose to, they will be assessed based on consistent and evidenced-based risk factors.

‘The assessments were so much better. One worker had been here three years and I didn’t recognise it was her assessment it was so much better and detailed.’

MARAM assessment tools

To support professionals in their risk assessment and management practice, FSV produced victim survivor focused MARAM Practice Guides and tools, publicly released in July 2019.

The tools are available for use across all service sectors and include screening tools, brief, intermediate and comprehensive risk assessments, child risk assessment tools, and safety plans. Use of these MARAM-aligned tools will promote consistent practice across the service system. They can be used by workforces directly, or incorporated into existing tools.

The MARAM Practice Guides and tools were developed through extensive consultation with more than 1,650 stakeholders, including experts such as the Commission for Children and Young People and peak bodies for Aboriginal community controlled organisations, men’s behavioural change programs, specialist family violence services, Victoria Police, Seniors’ Rights, Women with Disabilities Victoria, the Victim Survivor Advisory Council, government departments, and professionals. Consultation included organisations that specialise in working with Aboriginal communities, diverse communities, and older people experiencing family violence to support an intersectional lens and inclusive practice within the MARAM Practice Guides.

The user-feedback testing was positive, with specialist family violence practitioners commenting:

‘The safety plan was good. Little people are easily forgotten in times of crisis so I found the child tool really important.’

Online Tools for Risk Assessment and Management

A new online system, Tools for Risk Assessment and Management (TRAM), has been developed to host the suite of MARAM tools from screening, brief, intermediate, child and comprehensive assessment. The online risk assessment tools for adult and child victim survivors enable professionals to conduct individual assessments applying relevant questions based on community and identity, regardless of entry point into the service system.

TRAM is integrated within The Orange Door client relationship management (CRM) system and is being used in all The Orange Door services. It is accessible via a separate online portal for framework organisations outside of The Orange Door. Select specialist services are already using TRAM.

The use of TRAM assists framework organisations to align with MARAM by promoting consistent and collaborative practice across the service sector.

Key features of TRAM include that it:

- is built on the evidenced-based risk factors

- provides a visual summary of risk factors to assist in applying structured professional judgement in assessing the level of risk

- keeps perpetrators in view by highlighting all occasions a perpetrator is named as the predominant aggressor across all risk assessments within the service

- the use of TRAM is improving the risk assessments being undertaken as demonstrated by this case example provided by The Orange Door:

‘Wendy’, a practitioner at The Orange Door, conducted a family violence risk assessment for an adult victim survivor who has seven children. Wendy assessed each child as a victim survivor in their own right using TRAM.

Wendy acknowledged the shift in practice was challenging and took more time, but she uncovered pertinent risk information she would not have otherwise known.

Crucially, further information about the children’s mother’s level of risk was also obtained. Many perpetrators of family violence involve children in their violence to directly or indirectly target women as mothers or carers. Assessing each child informed the risk management actions that were taken for the children and their mother, including safety planning and further service engagement, as well as the required interventions for the perpetrator.

DHHS virtual assistant tool for housing officers

DHHS is developing a virtual assistant tool to assist public housing officers who work with clients experiencing family violence.

The tool gives staff immediate access to requested information in protocols and guidelines to support decision making, supervision, officer safety and wellbeing. If a housing services officer has a query, such as ‘What do I do if I suspect family violence?’, the virtual assistant returns the relevant housing guidelines, which will be aligned with MARAM.

A pilot of the virtual assistant has been completed and roll out is planned for the second half of 2019.

DJCS tools

The Youth Justice Case Management System includes a MARAM screen and comprehensive risk assessment tool.

Corrections Victoria has integrated MARAM concepts and assessment indicators into the new case management model, Dynamic Risk Assessment for Offender Re-entry (DRAOR), for offenders on a parole or post-sentence order. This ensures family violence is consistently considered as part of these assessments.

Courts case management system

The Courts will develop a new case management system that will record and appropriately share family violence risk assessment and management information. This includes providing for adequate ways to collect and record data, which will safeguard reporting obligations and assist in continuous improvement.

While awaiting development of this case management system, the Courts are planning to make interim upgrades to existing internal case management systems used by practitioners to incorporate MARAM including risk assessment tools.

Victoria Police Family Violence Report

Victoria Police commenced a statewide roll out of a new evidence-based family violence risk assessment and risk management tool known as the Family Violence Report (FVR). This tool is an enhanced version of the existing family violence report used by police (known as the L17) and is the means through which Victoria Police has operationalised MARAM for frontline police members.

The FVR contains a scored actuarial risk assessment tool that will help frontline police members to identify cases at increased risk of future family violence and the severity of the violence.

The FVR:

- introduces a process that triages cases to Family Violence Investigation Units for further review, prioritisation, comprehensive risk assessment and management intervention

- ensures consistent and relevant information is collected and shared with external support services

- guides members in applying evidenced-based practice

The FVR comprises 39 risk assessment questions, 15 of which are scored (and four of these 15 scored questions relate to high-risk factors in MARAM). Police members, like practitioners undertaking risk assessments, may use their professional judgment to override the score where high risk factors are otherwise identified.

From mid-July 2019, police members statewide have been able to complete the FVR in the field on mobile devices. It is expected that, for most police members, completing an FVR on the device while in the field will be quicker and capture more comprehensive and accurate information than completing the FVR back at the station at the end of a shift. This allows more time to be spent with family violence victim survivors.

Corrections Victoria

Corrections Victoria has updated tools and practice guidelines to embed family violence and begin alignment with MARAM, thereby providing for a consistent practice across the workforce:

Family violence is now included in the parole suitability assessment when recommending safe and stable housing for victim survivors of family violence.

A Family Violence Identification Form has been implemented in women’s prisons, which is completed within 72 hours of a woman's reception to identify if they have current or expired intervention orders, current or past experiences of family violence, and asking if they would like support in relation to this. This identification triggers referrals to relevant programs.

Corrections Victoria will focus future efforts on:

- synthesising content of the MARAM Practice Guides by including it in Corrections Victoria’s existing key practice documents

- supporting the development of perpetrator risk assessment and management tools

- reviewing assessment tools used in the Rehabilitation and Reintegration Branch one-day Family Violence Program pilot for offenders that are assessed as low and moderate risk of family violence

- embedding the Managing family violence in community correctional services practice guideline as part of business as usual case management activities and incorporating perpetrator tools, when available

- reviewing all identified policy and practice guidelines for changes to be made relevant to perpetrator tools

Action plans to implement change

As part of the change management process, departments are producing workforce-specific models, actions plans and frameworks with clear goals and procedures for achieving lasting change and aligning to MARAM.

Some of the frameworks have a focus on MARAM responsibilities of identifying, assessing and managing family violence risk. Other frameworks are not specifically MARAM focused but introduce the application of an intersectional lens across workforce practices, which is reflected in Principles 7 and 8 of MARAM.

Dhelk Dja and the Nargneit Birrang Framework

Dhelk Dja(opens in a new window) is the key Aboriginal-led Victorian Agreement that commits the signatories — Aboriginal communities, Aboriginal services and the Victorian Government — to work together and be accountable for ensuring that Aboriginal women, men, children, young people, Elders, families, and communities are stronger, safer, thriving and living free from family violence.

The Nargneit Birrang Framework(opens in a new window) will be released in early 2020. It sits under Dhelk Dja and will provide concrete guidance on how services can support a community-led response to family violence with Aboriginal communities.

The Nargneit Birrang Framework sets out six integrated principles:

- self-determination is fundamental

- safety is a priority

- culture, country and community are embedded in healing

- the past impacts on the present

- healing is trauma informed

- resilience and hope make a difference

Everybody Matters

Everybody Matters: Inclusion and Equity Statement(opens in a new window) was produced by FSV as the Victorian Government’s 10-year commitment to build a more inclusive, safe, responsive and accountable family violence system with the capacity and capability to meet the diverse and complex needs of all Victorians.

Everybody Matters embodies the principles of MARAM in signalling that family violence is unacceptable in any form, in any community or culture, that the drivers of family violence intersect with other forms of structural inequality and discrimination, and that there is a need for a workforce capable of providing responsive services that recognises the different experiences and vulnerabilities of different communities and age cohorts.

People within these communities can face multiple and intersecting barriers to reporting family violence, as well as in finding appropriate help and support.

Royal Commission into Family Violence(opens in a new window): summary and recommendations.

As an immediate action of Everybody Matters, an inclusion action plan for The Orange Door will be released in early 2020. The inclusion action plan will set out a three-year plan to embed inclusion, access and equity in The Orange Door services and policies.

The inclusion action plan recognises that communities are not homogenous, and individuals may be affected in different ways due to structural inequalities. It will ensure services for people from diverse communities are culturally responsive and safe.

A separate Aboriginal inclusion action plan will align with Principle 7 to ensure that services provided to people from Aboriginal communities are culturally responsive and safe.

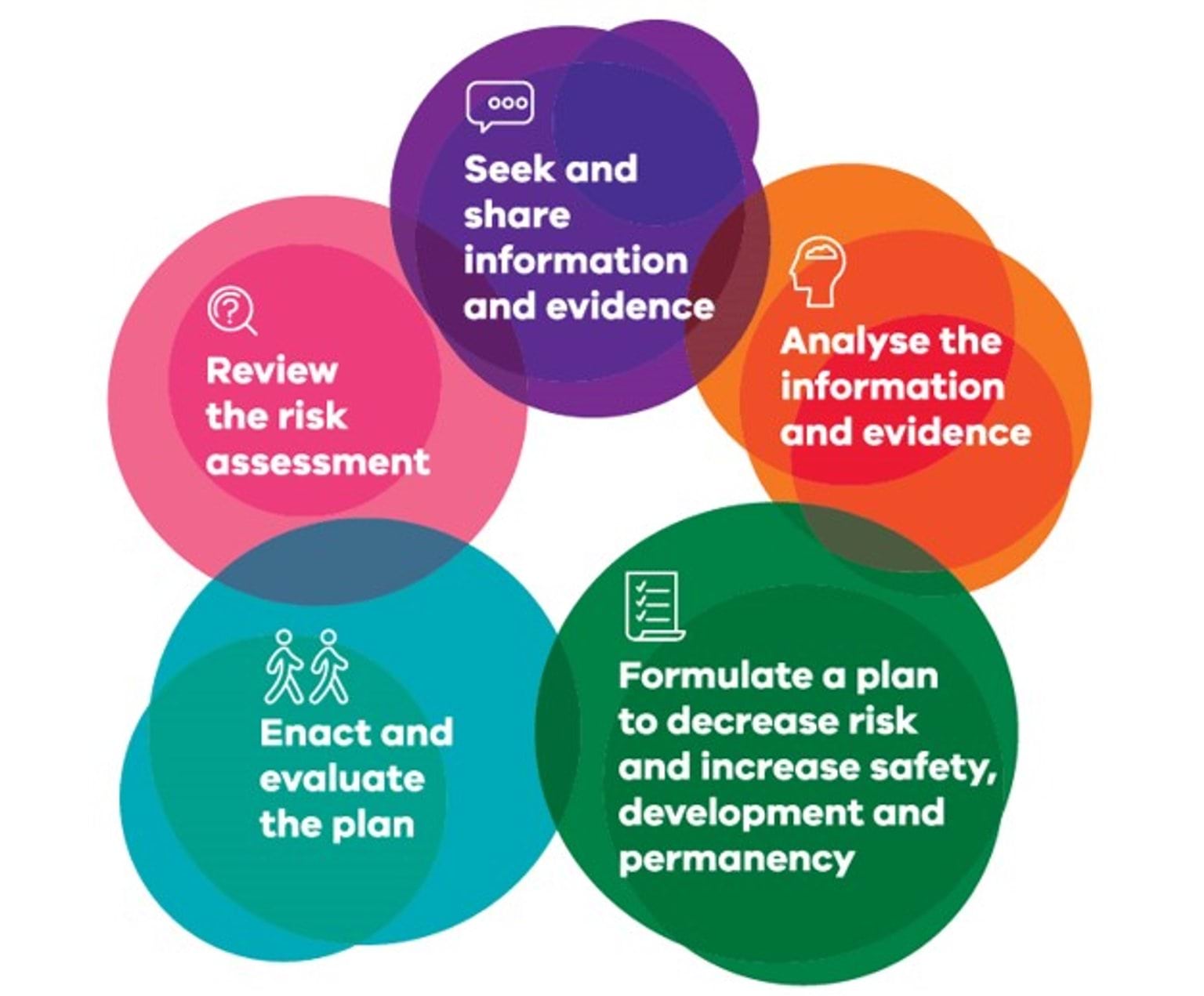

SAFER Children Risk Assessment Framework

The SAFER Children Risk Assessment Framework (SAFER) is a guided professional judgement approach and draws on MARAM and the Best Interest Case Practice Model.

The SAFER acronym summarises the following key practice activities:

- Seek and share information

- Analyse the information gathered to determine risk of harm

- Formulate a plan of action to address those risks and the child’s needs

- Enact the plan

- Review changes and reassess the risks

SAFER guides child protection practitioners in their day-to-day work in identifying, assessing and managing the risk of harm to children — including family violence risk — and facilitates planning for their safety and wellbeing. SAFER includes practice guides, tools and templates to support all Victorian child protection practitioners.

Specialist family violence and sexual assault services model and implementation plan

The service model for the specialist family violence and sexual assault services within the portfolio is being updated as part of new service agreements.

The service model will embed MARAM requirements as set out in the MARAM Practice Guides. In doing this, it ensures alignment across funded specialist family violence services.

Corrections Victoria family violence action plans

The Corrections Victoria Family Violence Action Plan(opens in a new window) underpins the Corrections Victoria Family Violence Strategy 2018–2021(opens in a new window). The 2018 Action Plan includes MARAM initiatives for employee training and embedding the MARAM into practice. Corrections Victoria will support implementation by aligning policies, procedures, practice guidance and tools with the MARAM. Corrections Victoria employees will be in the first tranche of people to receive training about the MARAM.

The Action Plan for 2019 has been developed and is currently awaiting endorsement.

Justice Health

The Justice Health Quality Framework has been reviewed. It sets out standards of care and is a contractual obligation for contracted service providers. Relevant sections were updated to align to responsibilities for information sharing and consultation under the MARAM Framework.

Setting up a capable workforce to identify, assess and manage family violence risk

Universal service systems that are available to all community members are ideally placed to play a much greater role in identifying family violence at the earliest possible stage. Associated systems such as Integrated Family Services, mental health and drug and alcohol services, aged care, and the health and education systems must play a more direct role in identifying and responding to family violence.

In order to achieve this, mainstream services will need to boost their family violence capability. Theses workforces need to recognise signs that family violence may be occurring and know what to do next to ensure safety.

Royal Commission into Family Violence:(opens in a new window) summary and recommendations.

Departments with framework organisations within their portfolios have developed substantial resources and invested in training and support to prepare workforces to align with MARAM.

This work has included:

- frameworks and strategies — whole-of-government and tailored strategies with a focus on workforce capability building which is aligned to MARAM

- resources and support for use by current and future staff — in addition to the consistent management systems and tools established across the service system, workforces are receiving specific MARAM resources and support for use in their work

- training — whole-of-government and tailored training is being delivered to all current workforces, and planned for future workforces

Workforce development: strategies, support and capacity building

Capacity building is taking place across the service sector.

Sector grants for sector capacity building programs

Across the system, peak bodies and statewide services have a role in developing standards, processes, and capability for their members to align with MARAM. The peak bodies also play an important role in communicating changes to standards, processes and government expectations.

With this pivotal role in mind, government has provided grants (in total nearly $1.5 million in 2018–19) to 11 key peaks and member organisations to support organisations in their relevant sectors to:

- implement the FVIS and CIS Schemes and MARAM in a consistent way

- support existing communities of practice or develop new ones

- provide expert input to the core resources

- develop initiatives to cater to diverse communities

In addition, six grants were provided to Aboriginal organisations to:

- tailor or develop resources for their member organisations

- share key learnings and develop resources across Aboriginal organisations

- provide an expert Aboriginal lens on the general sector grants efforts

Sector grants in action

Examples for how the sector grants have been used include the following:

- the Victorian Alcohol and Drug Association (VAADA) has used funding of $101,000 to support implementation, establish an Alcohol and Other Drug Family Violence Network (bringing together sector practitioners to promote collaborative practice). VAADA is also developing a Family Violence Capability Framework to articulate the appropriate knowledge and skills required in the sector

- the Municipal Association of Victoria (MAV) has been funded $130,000 to support maternal and child health services to align to MARAM, including the development of tailored implementation resources

- Maternal and Child Health (MCH) will be using funding of $130,000 to develop tailored MCH resources

- the Council to Homeless Persons will use funding of $101,000 to collaborate with broader peaks such as No to Violence and Domestic Violence Victoria to work in partnership on strategies and practice guidance to build sector capacity

The grant recipients are:

- CASA Forum

- Consumer Affairs (DJCS)

- Centre for Excellence in Child and Family Welfare

- Council to Homeless Persons (CHP)

- Drummond St Services on behalf of (with respect)

- Domestic Violence Victoria (DV Vic)

- Elizabeth Morgan House

- Justice Health (DJCS)

- Municipal Association of Victoria (MAV)

- No to Violence (NTV)

- Victorian Alcohol and Drug Association (VAADA)

- Youth Justice (DJCS)

Aboriginal organisations:

- Dardi Munwurro

- Djirra

- Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency (VACCA)

- Victorian Aboriginal Community Services Association Limited (VACSAL)

- VACCHO (funded until Dec 2019) and will participate in meetings until June 2020

DJCS Family Violence Workforce Development Strategy

DJCS is developing a Workforce Development Strategy which has the following objectives:

- an integrated approach to building family violence capability across the department

- all DJCS staff possess family violence knowledge and skills appropriate for their role and function, so that there is a shared understanding of this violence and the role that DJCS can play in its interactions with the broader family violence and universal service systems

- future workers to have the requisite capabilities in responding to family violence upon entry and ensure all staff receive relevant family violence professional development throughout their career in DJCS

- workforce development supports implementation of best practice approaches in responding to those subjected to or perpetrating family violence including risk assessment and management

The Strategy implements the MARAM Framework and focuses on embedding MARAM into existing DJCS policies, processes, practices and learning and development initiatives.

All agencies within DJCS are involved in the development of the Strategy.

DJCS Central Learning Repository / Family Violence Portal

DJCS is developing a Central Learning Repository or portal that will be accessible to funded agencies. It will contain a suite of MARAM materials customised for justice settings to support MARAM alignment.

This will be available in 2019–20 and will be accessible to all DJCS funded agencies.

Youth Justice

The Youth Parole Board Secretariat is working with FSV to develop an adolescent-specific component of family violence risk assessment, with the purpose of developing a coordinated and MARAM-aligned service response for adolescents who use family violence.

Additionally, the Youth Parole Board Secretariat will participate in program-specific reviews that will outline emerging practice and guide future learning in relation to family violence. The Secretariat will become involved in departmental pilot projects to trial new approaches, address service gaps and improve the effectiveness of family violence interventions for young people in contact with the justice system.

Corrections Victoria

Corrections Victoria will continue to align with the Specialist Family Violence Pathway.

Within its broader service delivery model, Corrections Victoria operates a Specialist Family Violence Pathway to address family violence perpetration. The Pathway allows the discrete identification of family violence perpetrators, and provides a pathway that targets family violence specific treatment needs. The Specialist Family Violence Pathway extends to perpetrators of family violence who are:

- on remand (unsentenced)

- sentenced to a term of imprisonment

- subject to a community correction order

The differentiated service response to perpetrators of family violence is shaped by a number of key practice principles, which extend and translate Corrections Victoria’s strategic frameworks into an evidence-based, targeted, and specialist service response.

As family violence does not always result in a criminal offence, and perpetrators of family violence may be in prison for other offences, identifying family violence is complex. Corrections Victoria has adopted criteria for the identification of family violence perpetrators in accordance with the definition of family violence in the Family Violence Protection Act 2008. During their intake process, offenders and prisoners are identified as family violence perpetrators, and therefore suitable for the Specialist Family Violence Pathway, based on these criteria.

The 2019 Corrections Victoria Family Violence Action Plan proposes a review of the Specialist Family Violence Pathway. The Pathway will be aligned with the MARAM perpetrator practice guidance once it is released.

Mental health and alcohol and other drugs

The Royal Commission into Family Violence found that mental health and alcohol and other drug (AOD) services must play a more direct role in identifying and responding to family violence, noting the need for health services to build capacity in these areas, and develop closer relationships with specialist family violence services.

In response to this recommendation, to improve understanding and capability in these workforces, specialist family violence advisor positions have been funded in these services to provide expert support and advice in identifying, recognising and responding to family violence.

The Victorian Alcohol and Drug Association (VAADA) is developing a family violence capability framework to guide and support AOD organisations with a better understanding of family violence across the sector which will align with MARAM. The framework articulates the appropriate knowledge and skills required to identify and respond to family violence. The framework will shape training, professional development programs and qualifications to align with the desired capabilities for family violence practice.

Child protection

The Family Violence Child Protection Partnership was implemented in response to Recommendation 26 of the Royal Commission, which called for flexible responses when family violence is present in a child protection context.

Recommendation 26 - 'The Department of Health and Human Services develop and strengthen practice guidelines and if necessary propose legislative amendments to require Child Protection — in cases where family violence is indicated in reports to Child Protection and is investigated but the statutory threshold for protective intervention is not met — [within 12 months] to:

Ensure the preparation of a comprehensive and robust safety plan, either by Child Protection or by a specialist family violence service

Make formal referrals for families to relevant services — including specialist family violence services, family and child services, perpetrator interventions, and the recommended Support and Safety Hubs, once established

Make formal referrals for children and young people to specialist services — including counselling services — if children or young people are affected by family violence or use violence.’

Royal Commission into Family Violence(opens in a new window): summary and recommendations.

The Partnership, which is managed by Family Safety Victoria, co-locates 17 specialist family violence practitioners and 12 senior family violence child protection practitioners in child protection offices across Victoria.

These positions strengthen child protection practitioners’ family violence knowledge and skills.

Housing delivered by DHHS

DHHS is currently undertaking the Strengthening Public Housing Practice in Family Violence Project which aims to build a shared understanding of family violence and workforce capability in identification and response to family violence for housing officers. A forum with senior managers will also be followed by a face-to-face training program across the state for up to 500 housing officers. This is expected to be delivered in the first half of 2020.

Maternal and Child Health

The 2017–18 State Budget included budget for an additional MCH consultation for families at risk of or experiencing family violence.

This additional family violence consultation aims to allow MCH practitioners to provide greater support to families in a way that best suits their needs and can be provided at any point in the family’s engagement with the service. This includes assessing and managing family violence risk and safety planning as required by Pillar 3 of MARAM.

MCH practitioners are supported to deliver this visit through the provision of tailored professional development.

Example of the MCH family violence consultations in practice

Katie is a 26 year old mother of a 12-month old baby boy. She lives with her partner Karl and his family. Katie’s extended family live overseas and she has no other family support here in Australia.

Katie has been attending the local MCH Centre. During her last visit, Katie disclosed many incidents of family violence.

The MCH nurse called the Family Violence Practitioner (FVP), who completed a comprehensive risk assessment and deemed her to be at high risk. A safety plan was devised. The FVP made a referral for family violence support, housing support and a notification to Child Protection. The FVP attended the Magistrates Court with Katie the following day to apply for an intervention order (IVO), which was granted immediately.

The FVP met with Katie again to devise an ‘escape plan’, as Karl was due home from overseas. Safe Steps provided accommodation for five nights until she was approved for a private rental property. The FVP attended the housing service with Katie to advocate for bond assistance and the first month’s rent and sourced funding for second hand furniture to furnish her new home. The FVP followed up with the family violence support service to ensure Katie would receive access to the Flexi Support Package (FSP)

Specialist family violence practitioners: perpetrators

FSV has established and is evaluating three streams of perpetrator interventions which align with MARAM to encourage perpetrators to acknowledge and take responsibility to end their violent, controlling and coercive behaviour. Principle 9 of the MARAM Framework: perpetrators should be encouraged to acknowledge and take responsibility to end their violent, controlling and coercive behaviour, and service responses to perpetrators should be collaborative and coordinated through a system-wide approach that collectively and systematically creates opportunities for perpetrator accountability. These interventions also raise capabilities in working with perpetrators.

Example case study provided by No to Violence

Alan was referred to a men’s behavioural change program (MBCP) following an incident with his girlfriend. Ongoing verbal abuse had escalated to physical violence. Upon referral, Alan reported significant mental health and drug and alcohol issues, and that he had been diagnosed with ADHD. Alan was referred to a trial program designed to work specifically with perpetrators with cognitive impairment and was assessed as having a significant undiagnosed communication disorder.

Alan is benefitting from the slower pace and structured breaks, which assists him with communication, attention, concentration and fatigue. Alan is engaged in the group process and is showing evidence of increased awareness of his behaviour. He is now recognising patterns of verbal abuse as family violence, its impact on others and shows insight. Alan continues to be motivated to change and has reported that instead of responding in a violent, abusive he ‘take[s] a deep breath walk[s] away for couple minutes’.

After a successful trial, perpetrator case management is now receiving ongoing funding. The purpose of case management is to provide an individualised and flexible response to address the needs of individual perpetrators, such as those with issues of alcohol and other drug (AOD) misuse, homelessness and mental health concerns. Since the start of the trial, perpetrator case management has provided a service response to over 900 clients.

Seven community-based perpetrator intervention trials have taken place to respond to critical gaps by delivering interventions to cohorts not adequately serviced by existing responses and to build the evidence base. This includes culturally and linguistically diverse perpetrators including new and emerging communities and Aboriginal communities. To date these seven trials have engaged over 100 participants.

In addition, Caring Dads is a 17-week early intervention program for fathers who use violence. The program focuses on the effect that a father’s violent behaviour has on their child and the child’s mother, encouraging responsibility for actions and developing skills in parenting. To date, the trial has provided interventions to more than 300 fathers and has also provided a service response to the children and mothers affected by the family violence.

Specialist family violence practitioners: adolescents who use violence

Principle 10 of the MARAM Framework requires a specialised response to adolescents who use family violence. Principle 10 of the MARAM Framework is that family violence used by adolescents is a distinct form of family violence and requires a different response to family violence used by adults, because of their age and the possibility that they are also victim survivors of family violence.

FSV currently funds three pilot programs focused on adolescents who use family violence. These services meet the needs of approximately 240 adolescents who use violence and their families.

The Orange Door Bayside Peninsula is working collaborative with Barwon Child Youth and Family (BCYF) to increase a shared understanding of adolescents who use family violence and enable sensitive and safe engagement with adolescents and their families.

FSV is in the early stages of designing and delivering a service model that is specific to Aboriginal young people and their families and aligned to Dhelk Dja. Funding is available for two years to enable this important work.

FSV is also working on comprehensive adolescent family violence practice guidance development and additional services responses, which will be reincorporated into the suite of MARAM Practice Guides and resources.

Specialist family violence practitioners: service for LGBTIQ families

w/respect, the new LGBTIQ family violence integrated specialist service, provides counselling, case management and recovery support services to people from LGBTIQ communities experiencing or using family violence.

The first of its kind in Australia, the w/respect service comprises a partnership of four well-known and respected LGBTIQ organisations — Drummond Street Services, Thorne Harbour Health, Switchboard Victoria and Transgender Victoria — supported by ongoing Victorian Government funding of $1 million.

The w/respect website withrespect.org.au(opens in a new window), which was formally launched at the Braiding Knowledge forum on 3 September 2018 by the Special Minister for State, the Hon. Gavin Jennings, provides comprehensive material on LGBTIQ family violence for mainstream service providers and first points of contact.

Specialist family violence practitioners: services for diverse communities

Principle 8 of MARAM requires that services and responses provided to diverse communities should be accessible, culturally responsive and safe, inclusive and non-discriminatory. In recognition of this, and to support culturally appropriate case management and family violence counselling, FSV is continuing to fund inTouch for family violence services. InTouch is a specialist family violence service that works with multicultural women, their families and their communities.

Victoria Police

As part of its reform program to improve its response to family violence, Victoria Police has established new Family Violence Investigation Units (FVIUs). FVIUs have been established within each police division and will be fully resourced by specialist detectives by January 2020. Each unit is led by a Detective Senior Sergeant and is supported by a team of detectives, intelligence officers, Family Violence Court Liaison Officers and dedicated police lawyers.

The FVIUs have the following functions:

- investigate serious and complex cases

- manage high-risk, complex and repeat cases

- support general duties police and specialist units

Once cases are received from frontline police, the FVIU utilises the Case Prioritisation and Response Model (refer to the ‘Victoria Police Family Violence Response Model’ section) to triage and determine the interventions required.

The FVIUs are fulfilling Pillar 3 of MARAM, enabling specialist police to assess and manage family violence risk.

The roll-out of specialist police in the FVIUs began in July 2018 and will continue into the next reporting period. By January 2020, there will be 415 specialist police roles focused on family violence and sexual offences across Victoria, who will receive targeted family violence training.

Consumer Affairs Victoria

Consumer Affairs Victoria (CAV) delivers the Financial Counselling Program (FCP) and the Tenancy Assistance and Advocacy Program (TAAP) through community organisations prescribed to align with MARAM.

To support change management, CAV has employed a part-time sector support officer whose role is to support the professional development of the FCP and TAAP workforce. This position will continue in 2019–20 to deliver tailored support for MARAM alignment.

Capacity building: an intersectional lens

Principles 7 and 8 of MARAM focus on services and responses to family violence being culturally responsive and safe for Aboriginal communities and diverse communities and older people.

Intersectionality Capacity Building project

Assessing and managing family violence risk with an intersectional lens is a key element of the MARAM Framework.

FSV’s Intersectionality Capacity Building project will develop a suite of resources to support capacity building to better understand, recognise and respond to the needs of people with lived experience of family violence underpinned by an intersectionality framework to align with MARAM.

The resources will support a whole-of-organisational approach for different service sectors to adopt and embed an intersectional approach to their work in responding to family violence.

Rainbow Health Victoria

Funding has been provided to Rainbow Health Victoria to develop and deliver a training module to help staff in family violence services understand the dynamics of family violence against people in LGBTIQ communities.

To encourage inclusive services, and to support LGBTIQ Victorians to feel confident in seeking support, FSV has funded 28 family violence service providers across the state to achieve Rainbow Tick accreditation. Rainbow Tick is a national accreditation program for organisations that are committed to safe and inclusive practice and service delivery for people from LGBTIQ communities. FSV has also funded Rainbow Health Victoria to develop and deliver a training module to help staff in family violence services understand the dynamics of family violence against people in LGBTIQ communities.

Aboriginal LGBTIQ people deal with overlapping forms of discrimination and power imbalances, including racism, and homophobia and/or transphobia. Responding to the need for an intersectional lens in practice, six Aboriginal organisations are currently funded by FSV to undergo Rainbow Tick accreditation.

Statewide inclusion advisors

Three statewide inclusion advisor positions are being piloted to build understanding and skills in the service system in relation to family violence for people from LGBTIQ communities, people with a disability, and women in or exiting prison.

The roles focus on building capacity within the sector to meet Principle 8, that services and responses provided to diverse communities and older people should be accessible, culturally responsive and safe, client-centred, inclusive and non-discriminatory. The roles also help services include an intersectional lens in their practice, as outlined in the MARAM Practice Guides and tools.

The advisors are:

- LGBTIQ inclusion advisor based at Domestic Violence Victoria and enhancing LGBTIQ inclusion in the family violence sector

- disability inclusion advisors based at Domestic Violence Victoria in partnership with Women with Disabilities Victoria leading the development of guidance to improve inclusion of people with disabilities, and improving identification and response

- Family Violence Justice based at Flat Out Inc. raising awareness of the circumstances and complex needs of women who have been in prison and experienced family violence

The Orange Door and Aboriginal Advisory Groups

To ensure a culturally safe and responsive service for Aboriginal people aligning with MARAM Principle 7, Aboriginal Advisory Groups (AAGs) have been established. The role of the AAGs is to inform decision making about operations of The Orange Door, in relation to the needs of Aboriginal communities across The Orange Door catchment area, and support engagement of Aboriginal services within The Orange Door.

AAGs have been established during the reporting period in the following areas:

- North Eastern Melbourne (established August 2018)