Any reform that requires a change to practice and ways of working relies on strong leadership. Leadership in these reforms requires:

- strategic plans for change management[4]

- governance to monitor and support implementation efforts

- consistent and accurate messaging

- ensuring sector readiness through implementation supports.

Section A: Family Safety Victoria as WoVG lead

Family Safety Victoria demonstrates leadership through coordinating and supporting the work taking place across the government.

MARAM governance for implementation

The Family Violence Reform Board, chaired by Family Safety Victoria, is the strategic leadership body for all family violence reforms, providing oversight and engagement across WoVG reform level issues.

The MARAM and Workforce Directors’ Group oversees the implementation of MARAM and the FVISS scheme. The Directors Group has oversight of budget expenditure, risks and issues of multi-lateral importance, and achievement of milestones and deliverables against agreed project plans.

Supporting these formal governance structures are:

- bilateral meetings between Family Safety Victoria and departments to promote proactive joint management of identified bilateral implementation issues

- manager workshops to discuss any multilateral developments or issues of WoVG relevance at policy level.

This approach provides a platform for strong and effective oversight of MARAM implementation.

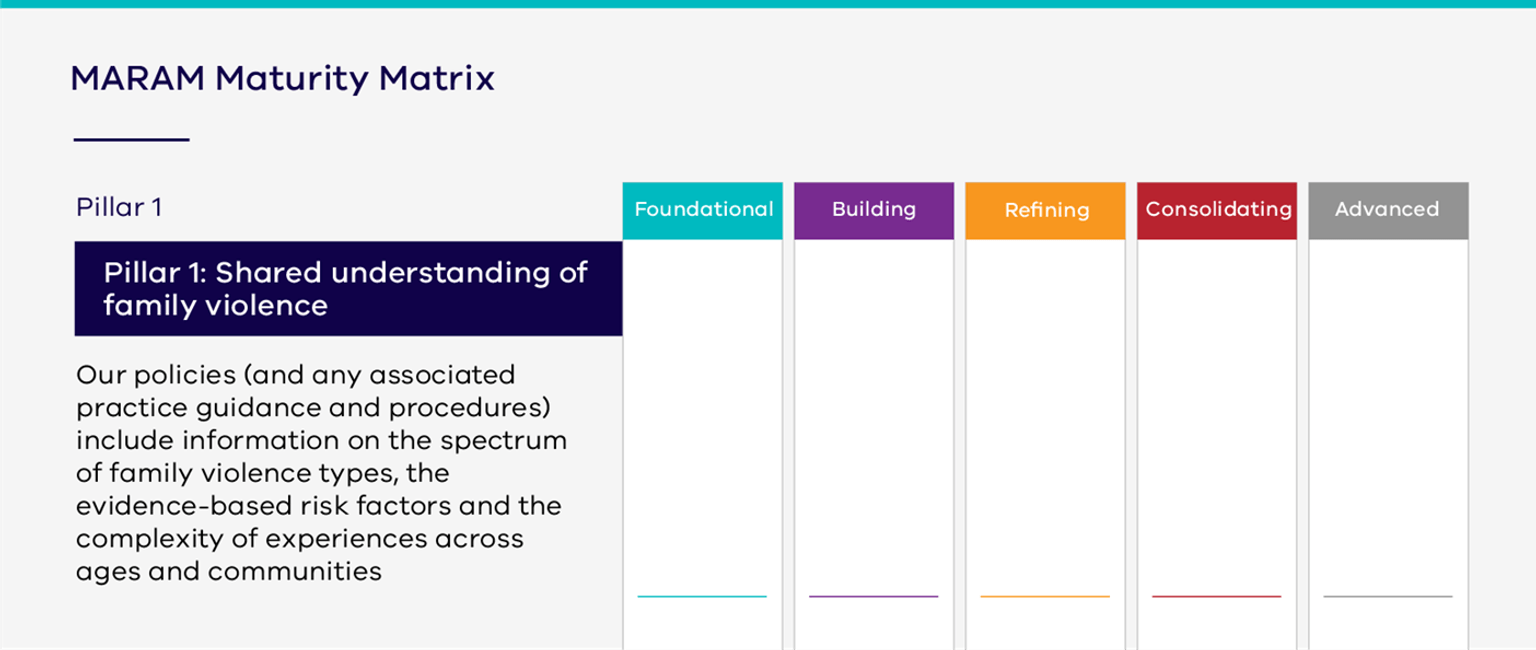

MARAM Maturity Model

The development of a MARAM Maturity Model was initially identified in MARAM as a core product to be developed. Subsequent reviews and evaluations strongly recommended the Maturity Model as a priority piece for implementation[5] [6].

The purpose of the Maturity Model is to provide a common language for organisational improvement through clear alignment milestones. This is achieved by describing the milestones in terms of outcomes, with measurement across a continuum from foundational to advanced.

The continuum will contain examples of each level to help an organisation assess its own progress against an objective scale. There will also be a suite of products to help organisations self-audit and progress in maturity along the continuum.

In progressing the Maturity Model project, Family Safety Victoria is demonstrating a clear commitment to leading reform outcomes. The Maturity Model will set clear standards and expectations for alignment, and large and small organisations will use this to improve their family violence response over time.

Given the complexities that apply to multiple services, it is anticipated that policy development and design for the Maturity Model will continue over 2022–23, with implementation not anticipated to start until 2023–24.

Related strategies, policies and action plans

MARAM sets responsibilities for responding to family violence, but also touches on many other government priorities and aspects of practice.

This includes embedding an intersectional approach in practice, workforce supply and retention, sexual violence and harm, Aboriginal cultural safety and perpetrator accountability. Key policies and government commitments that support and intersectwith MARAM implementation include:

- The Everybody Matters: Inclusion and Equity Statement articulates the Victorian Government’s 10-year vision for an inclusive, safe, responsive and accountable family violence system. Everybody Matters identifies and addresses the barriers that people from a diverse range of communities face when reporting family violence, and seeking and obtaining help. Everybody Matters emphasises the need to address systemic barriers to equitable service delivery and access that is underpinned by the theory of intersectionality.

- A forthcoming 10-year Sexual Violence and Harm Strategy is led by the Department of Justice and Community Safety, in partnership with the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing, to improve responses to sexual violence. MARAM will support risk identification and management across all key initiatives in the strategy that intersect with family violence.

- The Building from Strength: 10-year Industry Plan for Family Violence Prevention and Response outlines the Victorian Government’s long-term vision for workforces to prevent and respond to family violence. The building and retention of capable workforces are integral to supporting multi-agency collaborative practice and secondary consultations.

- The Dhelk Dja – Safe Our Way: Strong Culture, Strong Peoples, Strong Families (Dhelk Dja) agreement is the key Aboriginal-led Victorian agreement. It commits the signatories – Aboriginal communities, Aboriginal services and government – to work together and be accountable for ensuring that Aboriginal women, men, children, young people, Elders, families and communities are stronger, safer, thriving and living free from family violence. It requires the voices of the Aboriginal people across Victoria to be reflected in policy. The three-year action plans are delivered in partnership with the agreement’s signatories.

- The development of the Aboriginal Family Violence Industry Strategy under Dhelk Dja will provide a culturally informed framework to continue to build the capacity of Aboriginal services and its people in the family violence sector. Building on the strong foundations of experience in the sector, it will increase the number of Aboriginal people engaging in further education, prioritise Aboriginal-led family violence programs and prevention initiatives, and highlight the importance of Aboriginal culture in the sector.

[4] The Strategic Priorities of the MARAM Change Management Strategy are outlined at Appendix 7.

[5] The Cube report relates to the ‘Process evaluation of the MARAM reforms’ June 2020 evaluation by the Cube Group, which is not a publicly accessibly report.

[6] Monitoring Victoria’s family violence reforms: Early identification of family violence within universal services, May 2022, Report of the Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor.

Section B: Departments as portfolio leads

Departments demonstrate leadership through the tailored approaches they apply to their workforces, ensuring that the change management process is able to support them.

Department of Education and Training

The Department of Education[7] (formerly the Department of Education and Training) provide leadership and oversight of reform implementation through the Child Safety and Family Violence Project Control Board. The Project Control Board is governed by the Department of Education’s Executive Board as a decision-making body responsible for major project lifecycles (from design to evaluation).

It also manages the strategic direction, coordination and integration of child safety frameworks that include:

- the Child Safe Standards

- the Reportable Conduct Scheme

- information sharing and risk frameworks – the Child Information Sharing Scheme (CISS), FVISS and MARAM

- mandatory reporting in early childhood education and care settings, and schools

- criminal offences – a failure to disclose offence and failure to protect offence.

In the reporting period, the Child Safety and Family Violence Project Control Board has approved further targeted MARAM training, tools and reviewed guidance, and the approach to operating MARAM in education and care services.

The MARAM Annual Framework Survey noted that all Department of Education workforces who responded understood what organisational alignment to MARAM means, either in full or some aspects. It also highlighted that all Department of Education workforces who responded identified MARAM alignment as either a high or medium priority.

Department of Families, Fairness and Housing

In 2021–2022, the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing demonstrated clear and consistent leadership through their work on the practice change strategy and in The Orange Door. The inaugural MARAM and Information Sharing week was held from 26 to 29 April 2022. The event was officially opened by the Secretary to the department, Ms Brigid Sunderland and closed by The Hon Gabrielle Williams MP the then Minister for Prevention of Family Violence.

The week comprised 4 webinars of 2 hours each, with a keynote speaker and a panel discussion with experts and people with lived experience of family violence.

The topics were:

- Collaborative practice — sharing information to identify, assess and manage risk to children and families

- Child-centred practice — working with children and young people

- Intersectionality in practice

- Coercive and controlling behaviours and working with people who use violence.

Over 2,000 people registered for the event, with more than 300 people at each session. Attendees were from across the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing workforces, including public housing, community housing, homelessness services, multicultural and settlement services, Child Protection, child and family services, and aged care services.

A highlight was the presentation led by honoured guests, Sue and Lloyd Clarke, founders of the Small Steps for Hannah Foundation and recipients of the 2022 Queensland Australian of the Year award, for their advocacy in raising awareness of coercive control as a form of family violence.

In 2020–21, the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing reported it was developing a MARAM Enabling Practice Change Strategy. This is an internal document to complement formal learning opportunities to apply MARAM practice on a daily basis. The strategy includes a series of behaviour statements to build practitioner confidence and competence in recognising and responding to family violence within the context of their work.

The strategy has now been completed and is used by Department of Families, Fairness and Housing program areas as a resource to retain MARAM consistency when tailoring resources.

The Orange Door network has also demonstrated clear and consistent leadership, as new sites continue to be opened across the state. This includes operationalising the Inclusion Action Plan for The Orange Door, which outlines the baseline and key measures to ensure all users of The Orange Door feel safe, welcomed and respected. There are 18 Aboriginal Cultural Safety Advisors across The Orange Door network, who have been funded to embed the Strengthening Cultural Safety in The Orange Door project. All sites will undertake a Cultural Safety Assessment, and create and implement rolling action plans.

The MARAM Annual Framework Survey notes that all but one human services respondent indicated they understand what organisational alignment to MARAM means, either in full or some aspects. It also highlighted that most human services workforces who responded identified MARAM alignment as either a high or medium priority. However, 12 services identified MARAM alignment as a low priority or were ‘not sure’ of priority, suggesting there is further work required to reach all organisations.

Department of Health

The Department of Health has worked closely with respected health services to provide clear and consistent leadership. In 2021–22, leadership activities have been undertaken with Ambulance Victoria and health services, through the Strengthening Hospital Responses to Family Violence (SHRFV) initiative.

Ambulance Victoria has undertaken a MARAM organisational audit and made key recommendations to drive alignment. It has led briefings on MARAM alignment to Ambulance Victoria leaders, and presented at organisational governance committees, such as the Best Care Committee and the Consumer Advisory Council.

The SHRFV initiative has led alignment across multiple health services through the development of guidance that supports mapping

of MARAM Responsibilities, and aligning policies and procedures.

For community health services, early parenting centres, hospitals and bush nursing centres, the Department of Health has initially focused on delivery of consistent and accurate messaging, to support sector readiness and long-term culture change.

The Department of Health has also demonstrated leadership in response to family violence by prioritising the development of resources to support healthcare workers who are experiencing family violence.

The MARAM Annual Framework Survey notes that health workforces primarily agreed that they understand what organisational alignment to MARAM means, either in full or some aspects. Most health workforces also identified MARAM alignment as a high or medium priority for their organisation. Only 2 health services who responded did not understand what MARAM alignment means.

Out of 102 responses, 9 health services rated MARAM as a low priority, not a current priority or ‘not sure’. As noted above, these results should be interpreted in the context of health services only being prescribed in 2021, and the ongoing impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health services. It is clearly evident that despite the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, the training numbers achieved, and successful embedding of training and establishing collaborative practice and referral pathways, are significant and are a testament to the effectiveness of the SHRFV initiative. These achievements reflect the commitment from Victorian hospitals and health services to embed systems, structures and processes that will identify and respond to family violence.

Department of Justice and Community Safety

The Department of Justice and Community Safety convenes the MARAM and Information Sharing (MARAMIS) Working Group, chaired by the Director of the Family Violence and Mental Health Branch. This working group includes members from across the Department of Justice and Community Safety, including Victim Services, Support and Reform (VSSR), consumer affairs, liquor, gaming and Annual report on the implementation of the Family Violence Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management Framework 2021–22 25 dispute services, Corrections and Justice Services (CJS), and Youth Justice. The group works collaboratively to support the ongoing reforms and implementation across the department.

CJS has expanded its established family violence governance arrangements by introducing a CJS MARAM Group, in addition to the CJS

Family violence Steering Committee, which holds responsibility of CJS’s MARAM alignment. The CJS MARAM Group provides a platform for information sharing, collaboration and awareness of the work being undertaken on family violence.

The Department of Justice and Community Safety has funded roles across the portfolios to directly support change management. These

include:

- MARAM Sector Support Officers in consumer affairs, liquor, gaming and dispute services, Justice Health, VSSR, the Koori Justice Unit and Youth Justice (which receives extra funding from Family Safety Victoria)

- 2 CJS Family Violence Practice Leads, who have commenced mapping current processes to identify suitable solutions to align to MARAM

- a MARAM Change Manager in CJS.

Three Family Violence Practice Lead roles in the Victims of Crime Helpline play a critical role in building family violence capability and embedding MARAM into practice. The Family Violence Practice Leads also provide subject matter expertise in working with male victims of family violence. The roles provide opportunities to upskill other workforces on how to work safely and effectively with male victims, which include supporting increased capability in predominant aggressor identification.

The MARAM Annual Framework Survey notes that all Department of Justice and Community Safety workforces who responded understand what organisational alignment to MARAM means, either in full or some aspects. It also highlighted that all justice workforces who responded identified MARAM alignment as either a high or medium priority.

The courts

An internal working group was established by the Magistrates’ Court of Victoria (MCV) in 2021, bringing together expertise to plan for the implementation of adults using family violence MARAM responsibilities, practise guidance and tools. This includes mapping of court roles to

each responsibility, tailoring and embedding of tools, and assessing changes to systems, tools, policies and procedures.

MCV has also shown leadership in ensuring that MARAM-aligned practice is embedded within the 7 new Specialist Family Violence Courts. This will support strengthening family violence capability within the MCV. MARAM Annual Framework Survey results are not available for the courts as an entity within the Justice portfolio.

Victoria Police

Victoria Police is a critical workforce to support initiatives that develop and embed practice. This is particularly the case with working with persons who use family violence.

In consultation with the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing, and Family Safety Victoria, Victoria Police led the development of a strategic intelligence assessment to examine the incidence and numbers of youth issued with a Family

Violence Intervention Order.

The assessment was delivered in August 2021 to assist the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing understand the number of youths that may require crisis accommodation. Key findings from the intelligence assessment and stakeholder engagement indicated that police would also benefit from the development of specific practice guidance.

As a result, the internal practice guidance, Responding to Adolescent Family Violence, was published in January 2022. The guidance promotes consideration of early childhood experiences of trauma, confirmation of emergency accommodation, and the support of cautions and diversions, to avoid further contact with the justice system for young people.

A project has also been established in Family Violence Command to refine Victoria Police policy and progress activity regarding predominant aggressor identification, to reduce the occurrence and impact of misidentification by police.

This work will be completed in conjunction with the outcomes of the Misidentification Predominant Aggressor Working Group. This Working Group, led by the Department of Justice and Community Safety, brings together Victoria Police, MCV and legal services, Child Protection and support services.

The Working Group addresses issues such as:

- supporting and providing training to police officers to identify the predominant aggressor before commencing a risk assessment, and before it is committed to the Law Enforcement Assistance Program crime database

- reviewing how family violence records are captured in the Law Enforcement Assistance Program crime database to ensure that when misidentification has occurred, remedial action is taken to resolve the issue

- developing a clear process for an urgent return to court in matters where misidentification has occurred

- working with other services, such as Child Protection and The Orange Door, to deliver greater clarity on reporting concerns and providing support, and to ensure that when they do address protective concerns, perpetrators are also held to account.

- MARAM Annual Framework Survey results are not available for the Victoria Police as an entity within the Justice portfolio.

[7] The Department of Education and Training was renamed The Department of Education in January 2023 following Machinery of Government change.

Section C: Sectors as lead

Funded sector capacity-building participants have consistently demonstrated leadership in embedding the reforms within their workforces.

Some highlights include:

- The Council to Homeless Persons has developed a Specialist Homelessness Sector Learning Hub to demonstrate an evidence based, shared understanding of family violence risk and impact. The Learning Hub is a central place to host useful MARAMIS learning products and resources that are relevant to the homelessness services sector.

- The CFECFW developed and released an Emerging Themes video series that explores common themes across MARAM, FVISS and CISS for all workforces. The videos support MARAM learning across the sector and can be embedded into an organisation’s own learning and development system. They also provide clear and consistent leadership on recognising children as victim survivors of family violence, and safe and effective engagement with young people.

- Court Network is a community organisation providing non-legal information, referral and support to court users via telephone, online and in court. Court Network provides trained volunteers in all Victorian court jurisdictions and at 28 courts. Court Network empowers and increases the confidence of court users to manage their court matters through before, during and post-court options for engagement. It developed the Court Network Volunteer Family Violence Practice Guide to provide consistent messaging and leadership to volunteers.

- VAADA produces a monthly newsletter as part of its communications strategy. This is sent to alcohol and other drug workforces and includes items that are specifically related to MARAM. It also promotes the availability of MARAM training and Family Safety Victoria updates, as well as news from the broader family violence sector. The first newsletter received close to a 40 per cent click-to-open rate, which is far above the industry standard of around 26 per cent.

- Jewish Care delivered a series of E-bulletins consisting of 27 resources to prescribed organisations. The E-bulletins included resources to clarify the requirements of phase 2 organisations to align to MARAM, support organisational leaders to align to the MARAM Pillars, and to support workers who are new to family violence to embed MARAM tools into their practice.

- Dardi Munwurro completed a workforce mapping exercise across all programs and services, to determine the MARAM Responsibilities that are applicable to its staff. There are 95 per cent of Dardi Munwurro staff who now understand the requirements needed to align their practice to the MARAM framework.

The Orange Door

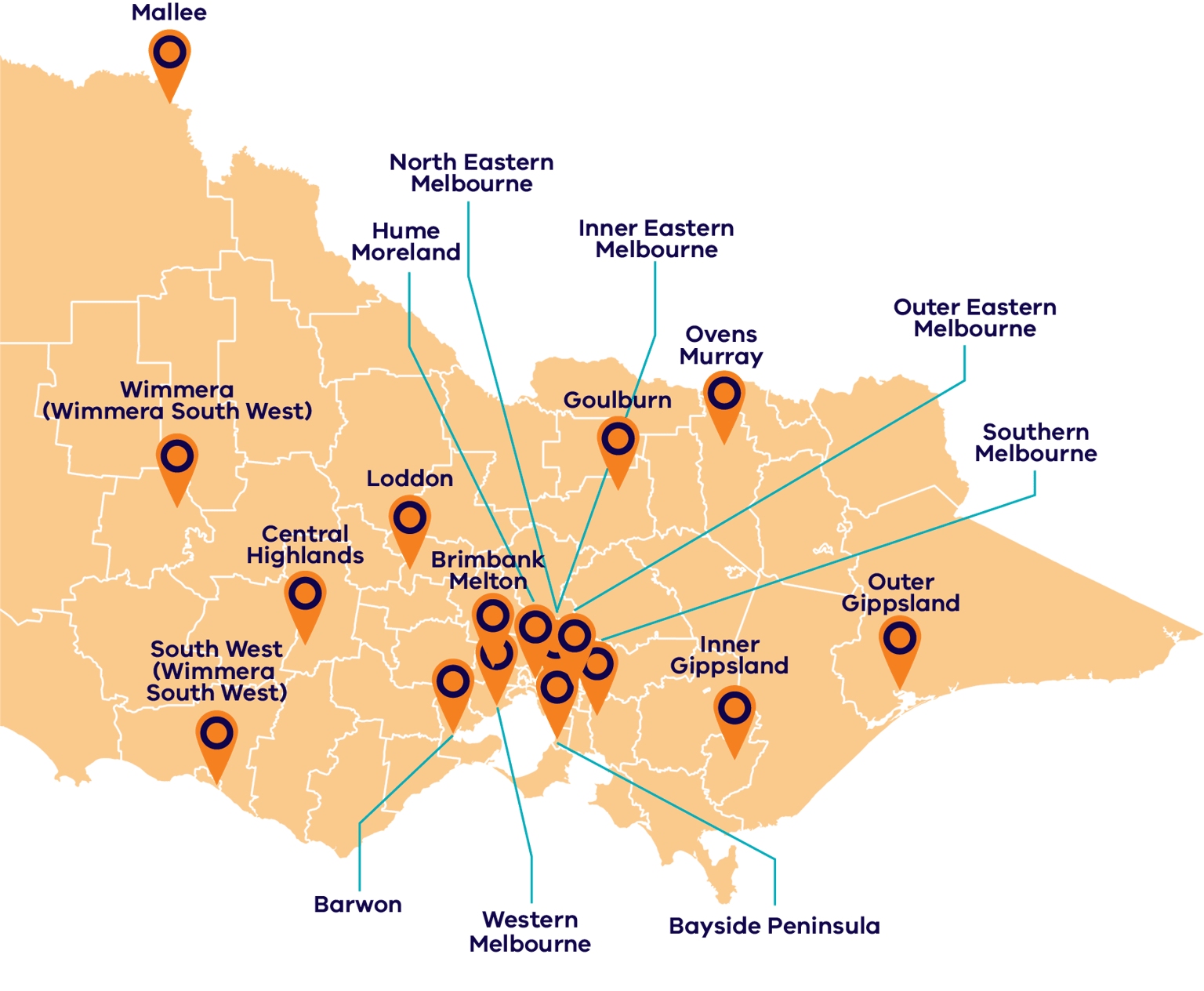

The Orange Door network was established in response to Recommendation 37 of the Royal Commission for ‘a single, area-based and highly visible intake point’ to be available in each Department of Families, Fairness and Housing region.

The Orange Door is a free service for adults, children and young people who are experiencing or have experienced family violence, and families needing support with their wellbeing and development of their children. It assesses and responds to a person’s immediate needs and risk, and connects people to family violence services, ACCOs, family services and services for people using violence.

The Orange Door network provides coordinated support, including crisis assistance and support, risk and need assessments, and safety planning, as well as supporting people to connect to other services for longer-term support.

In 2021–22, The Orange Door network finalised the statewide rollout, so that no matter where people experiencing family violence live, they can now access support through The Orange Door network.

Operational guidance for The Orange Door is developed in consultation with key stakeholders, including MARAM and Practice Development teams in Family Safety Victoria, to ensure the guidance is aligned to MARAM.

Since its inception in 2018, The Orange Door network has assisted more than 238,000 people, including 95,000 children statewide. It has also completed 82,051 risk assessments and safety plans. This is a clear example of the outcomes that can be achieved with clear leadership.

| Case Study: The Orange Door |

|---|

|

The Bandara family attended The Orange Door seeking financial assistance to buy food and other items. Dayani* and Fernando* were unable to access income support as they were seeking asylum in Australia. The family was being supported by a number of agencies, including health and culturally specific organisations. Dayani shared a recent family violence incident resulting in Fernando being served with a limited intervention order, with conditions. Dayani wished to remain in the relationship and the family home, and was concerned for Fernando’s wellbeing. The Orange Door practitioner undertook a MARAM risk assessment and went through a MARAM safety plan with Dayani, which included advising her of support options, as well as strategies in the event of family violence continuing. Dayani declined family violence support, as she was satisfied with the therapeutic support she was receiving from her culturally specific organisation. With Dayani’s consent, The Orange Door contacted the organisation and shared Dayani’s MARAM safety plan and The Orange Door’s MARAM family violence assessment. During Fernando’s assessment, he discussed his use of violence, lack of employment, depression and substance misuse. He acknowledged his values and belief systems had shaped his choice to use violence. The practitioner referred Fernando to a culturally specific Men’s Behaviour Change Program specialising in cultural values and issues relating to migration that may be contributing factors to family violence risk. Fernando also agreed to engage in a drug and alcohol service. The Orange Door practitioner and Fernando contacted the service together, and completed a preliminary assessment and arranged a follow-up appointment in 2 days. The Family Services worker undertook to coordinate a case conference with the professionals involved after their home visit, and continued to monitor and assess the family violence risk. Note: Risk assessments and safety plans would also be undertaken on the children’s experience of family violence. *Not their real names. |

| Case Study: Safe Steps |

|---|

|

Tanya* called Safe Steps on a Sunday afternoon while her partner and her children were away from home. She was not sure why she called Safe Steps, describing herself as in an ‘ok’ marriage with fights time to time like ‘most normal relationships’. The crisis response worker identified some common indicators of trauma based on using her professional judgement. Minimising risk to safety is a common response of victim survivors. Tanya agreed to participate in a discussion to inform a MARAM risk assessment. The assessment identified a range of serious risk factors and determined Tanya’s risk level at ‘serious risk’. This included physical harm, sexual assault, controlling behaviours and financial abuse. Tanya was being prevented from training to return to the workforce, as well as access to the doctor. Tanya decided to stay in her relationship for the time being. Using the MARAM risk assessment tool helped Tanya understand that what she was experiencing was family violence and enabled her to take steps to engage in safety planning. Tanya was supported to understand that help is available if she needs to leave the relationship or if risk escalates and she needs support for her safety. Note: Risk assessments and safety plans would also be undertaken on the children’s experience of family violence. Information would be sought about the perpetrator to understand other risk factors present. Referral to therapeutic supports for Tanya and children would be supported. *Not their real names. |

The Safe Steps case study demonstrates the use of:

- a MARAM Risk Assessment

- MARAM Safety Plans

- respect for the victim survivor’s agency

- trauma-informed practice

- the use of structured professional judgement.

Summary of progress

Family Safety Victoria, government departments and the sector are working hard to communicate the intent and impact of the reforms to workforces, and to create systems for feedback and continuous improvement.

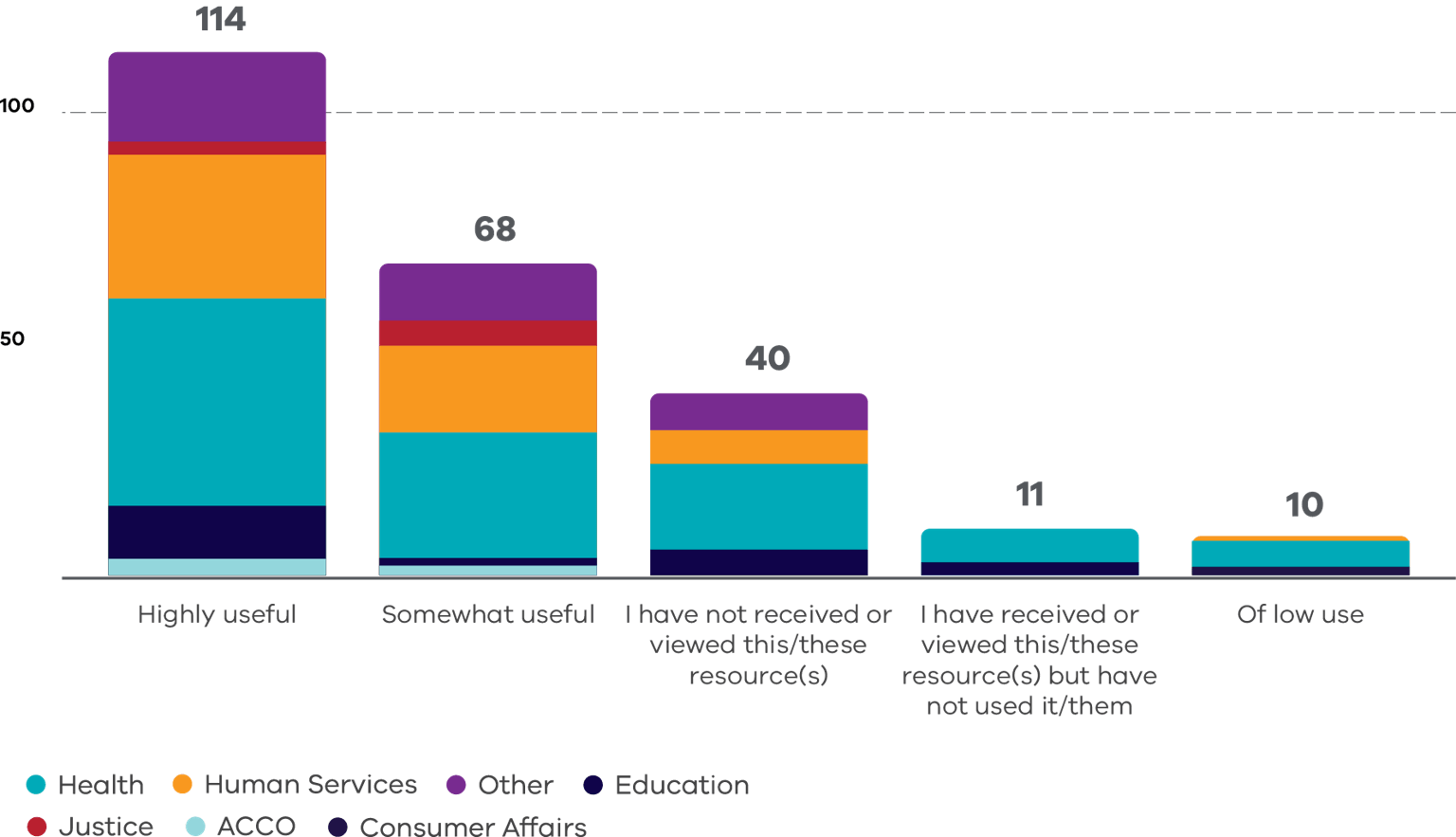

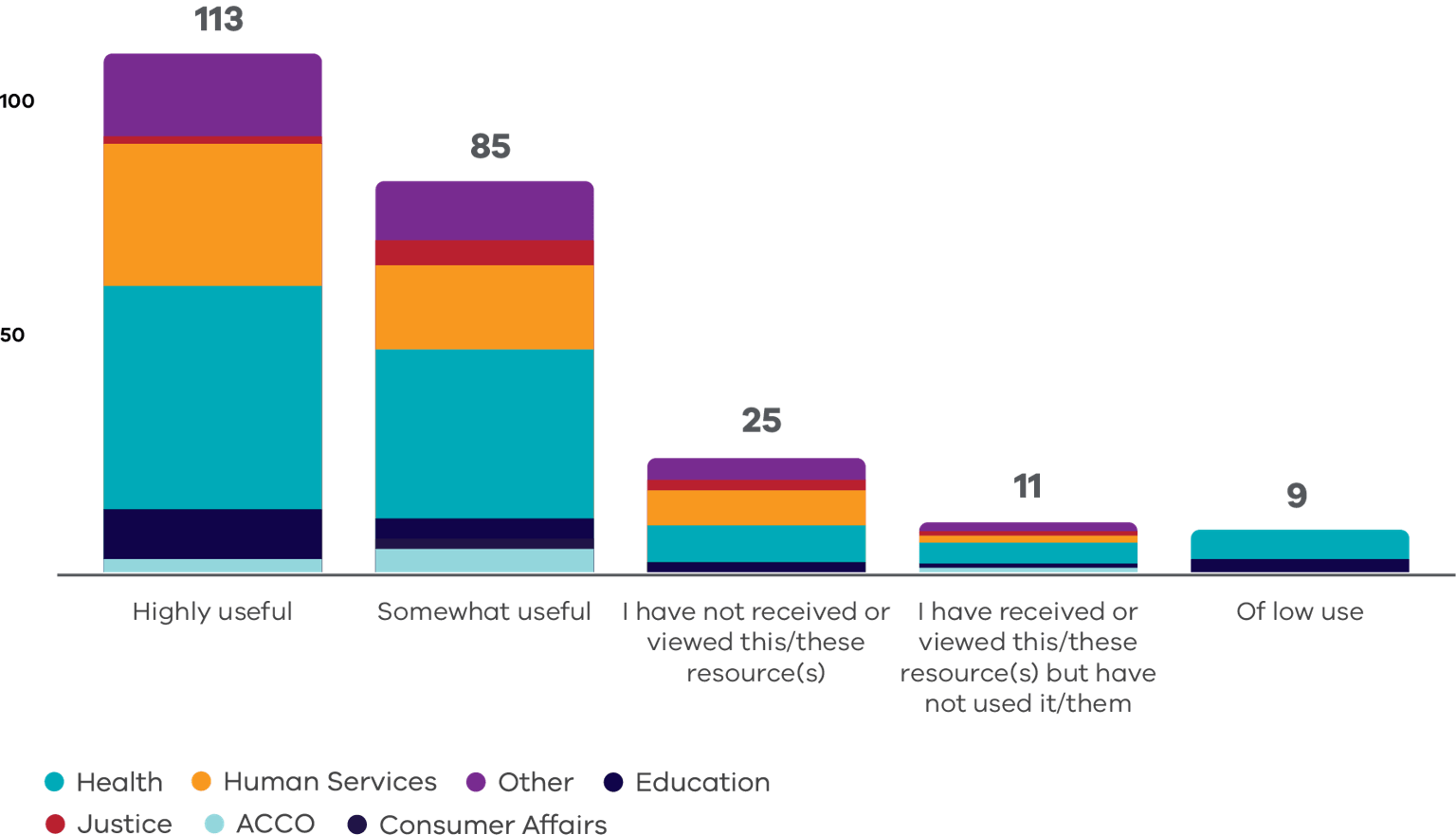

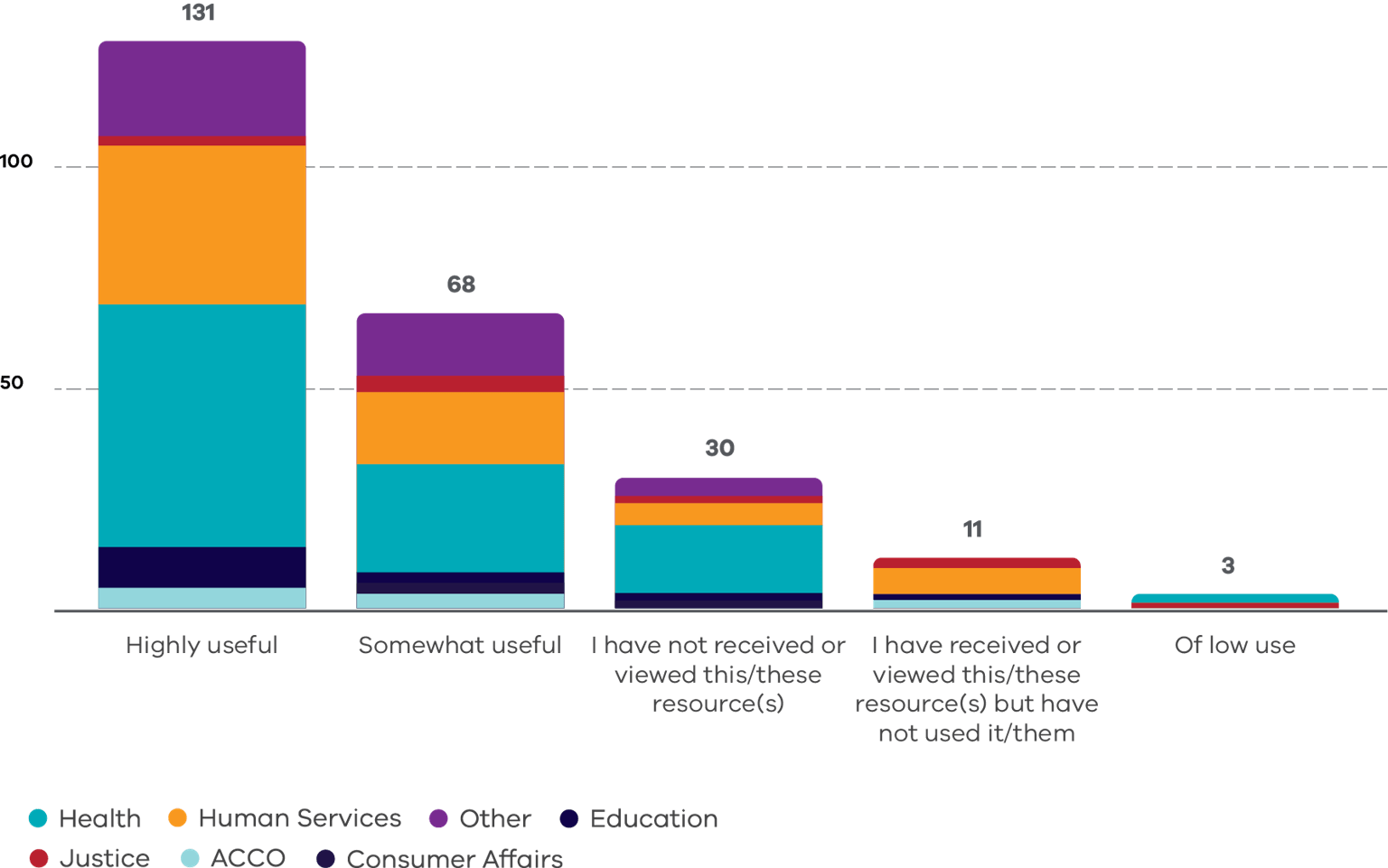

The MARAM Annual Framework Survey results confirm that:

- 74 per cent found Family Safety Victoria communications and information highly or somewhat useful

- 81 per cent found department communications and information highly or somewhat useful

- 82 per cent found peak body communications and information highly or somewhat useful

- 73 per cent found management communications and information highly or somewhat useful.

This suggests that there is some room for improvement in how messaging is reaching workforces, and to determine what communications and information are the most effective. There are limited mechanisms for drilling down further into this feedback, but opportunities to engage with workforces will be considered.

Updated