One objective of MARAM is to ensure its consistent use across prescribed organisations[8] and services. Pillar 2 expands on this to require organisations to have a ‘shared approach to identification, screening, assessment and management of family violence risk’. This is achieved using tools consistent with the MARAM evidence-based risk factors.

Consistent practice does not require using the MARAM practice guidance and tools in their original form. This would not allow for the nuance across multiple services and practices. Instead, it requires services in education, health, justice and community to base their practice on MARAM practice guidance and tools. The purpose is so that family violence risk is assessed and managed on the same understanding and evidence base, no matter the service engaged with.

Consistency also improves collaboration, as services are able to use the same language and understanding of family violence risk to work together to keep victim survivors safe and perpetrators accountable.

Family Safety Victoria creates centralised, evidence-based resources that are shared with departments and sectors to tailor and embed into their workforces.

This chapter summarises the work of:

- Family Safety Victoria to continue to develop centralised resources required to support MARAM

- departments to interpret and tailor the centralised resources into workforce operational contexts

- sector peak bodies to bring the practice to life directly with practitioners.

[8] A full list of MARAM prescribed organisations is provided at Appendix 1.

Section A: Family Safety Victoria as WoVG lead

MARAM Practice Guides and Tools

The adult perpetrator-focused MARAM Practice Guides and tools were developed throughout 2020 to 2022, in partnership with NTV. The guides and tools were released in July 2021 for non-specialist workforces, and in February 2022 for specialist workforces.

The guides draw on a range of evidence and best-practice models available across Australia and internationally. Over 1,000 professionals were extensively consulted to develop the guides.

The perpetrator-focused MARAM Practice Guides and tools include guidance on broad-ranging areas of practice. They promote victim-centred practice, an intersectional and a trauma-and-violence-informed lens, and an understanding and assessment for coercive control, across types of relationships, identities and community groups[9].

Guidance and a tool are also included to support the accurate identification of the predominant aggressor/perpetrator. This is the first misidentification tool developed for statewide use in Australia. Accurate identification of the perpetrator of family violence is a critical component of risk assessment and risk management.

The MARAM Practice Guides highlight the use of systems abuse and provide professionals with guidance on identifying and mitigating any immediate and long-term impacts caused by misidentification or system errors.

The misidentification guidance and tool were developed in consultation with Victoria Police, the Magistrates’ Court, Victims of Crime Helpline, Child Protection, NTV, Safe and Equal, the Victim Survivor Advisory Council[10]. Professionals working with Aboriginal and diverse communities also contributed to the tool and guidance development.

Increased use of MARAM online tools in specialist services

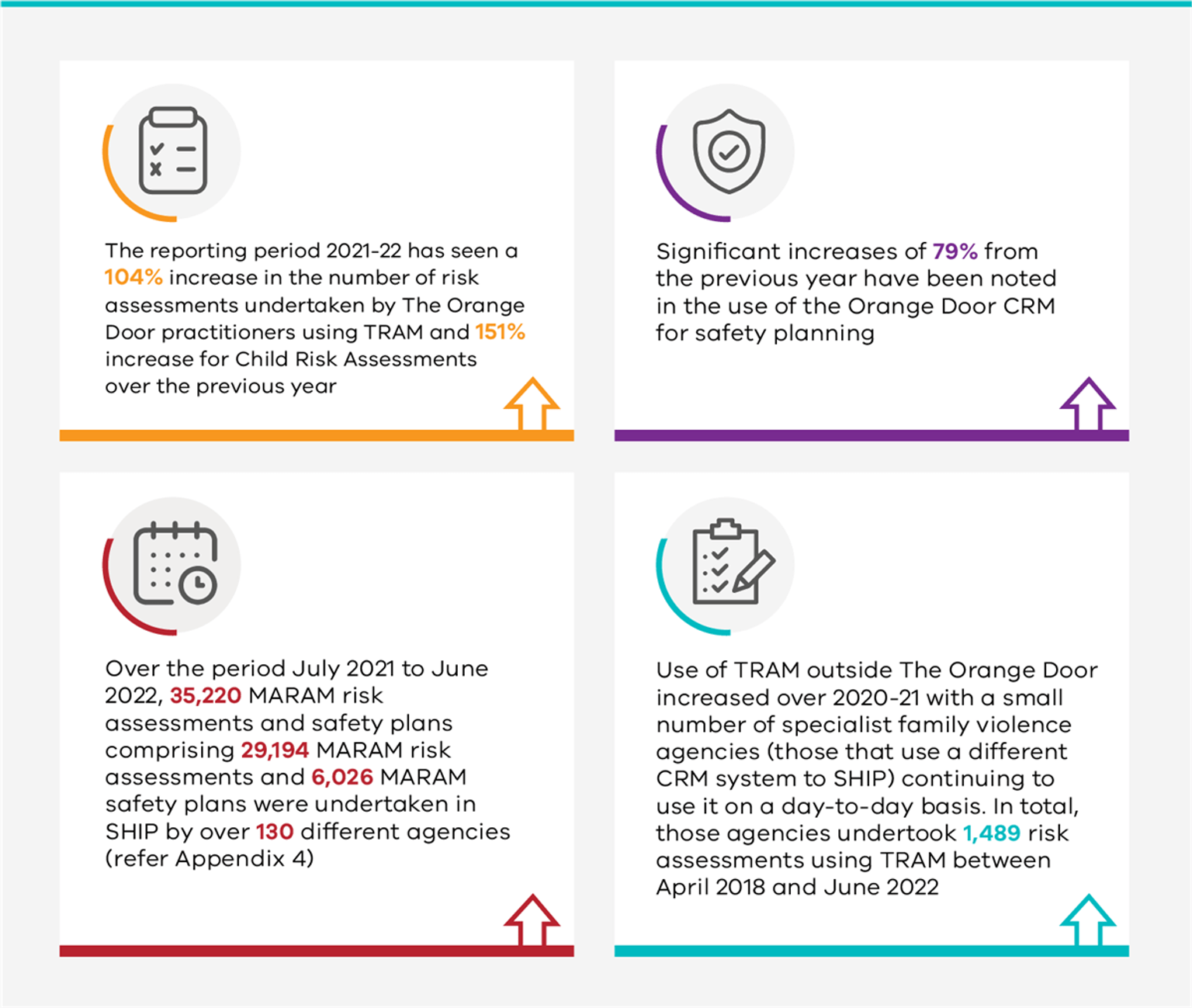

Tools For Risk Assessment and Management (TRAM)[11], The Orange Door Client Relationship Management System (CRM)[12] and the Specialist Homelessness Information Platform (SHIP)[13] are the online data systems that provide access to MARAM tools for use by practitioners to conduct risk assessments and safety plans. They are primarily used by Specialist Family Violence Services and homelessness services. Their availability is being extended to new organisations to support consistent use of MARAM tools across these services.

The continued year-on-year increases suggest numerous contributing factors, such as:

- the increasing number of The Orange Door sites opening across Victoria

- caseloads

- the number of on-ground practitioners

- greater risk assessment and management confidence

- an increase in the number of services conducting the assessments.

[9] As outlined in the MARAM Foundation Knowledge Guide, coercive control is a pattern of behaviours, including emotional, financial, controlling, sexual and physical violence. The behaviour is intended to harm, punish, frighten, dominate, isolate, degrade, monitor or stalk, regulate or subordinate the victim survivor.

[10] The Victim Survivor Advisory Council was formed in July 2016 to give people with lived experience of family violence a voice, and to ensure they are consulted in the family violence reform program. Members are appointed by the Minister for Prevention of Family Violence.

[11] TRAM: Tools for Risk Assessment and Management are used by practitioners in The Orange Door for risk assessment, and a select number of specialist family violence agencies for risk assessment and safety planning.

[12] CRM: Client Relationship Management system is used by practitioners in The Orange Door for safety planning.

[13] SHIP: Specialist Homelessness Information Platform is used by specialist family violence and homelessness services for risk assessment and safety planning.

Section B: Departments as portfolio leads

Department of Education

To support the development of consistent practice, the Department of Education developed an information-sharing and family violence reforms toolkit and guidance. The toolkit sits alongside and complements training and eLearning modules (see Chapter 8) provided to centre-based early childhood education and care services, schools, system and statutory bodies, education health, wellbeing and inclusion workforces, and Department of Education corporate workforces.

The toolkit contains templates, checklists and materials that can be adapted to meet the needs of the school, service or organisation. The guidance has been developed to provide general information and support for education and care workforces that are authorised to use the reforms. The toolkit and guidance support the legally binding Ministerial Guidelines for CISS and FVISS. Hard-copy versions of the toolkit were mailed out to all centre-based early childhood education and care services, and schools in Terms 3 and 4, 2021.

Family Safety Victoria and the Department of Education also provided Early Childhood Australia (ECA) with funding to scope the family violence identification and response needs of the centre-based early childhood sector to align with MARAM and capability frameworks. ECA also developed a MARAM toolkit, including tools, resources, policies, procedures and guidance to support MARAM alignment and workforce capacity building, and to complement the Department of Education’s information-sharing and family violence reforms guidance.

The ECA toolkit was piloted in 5 early childhood services. Before piloting commenced, the 5 pilot services were surveyed in 2021 to understand how confident staff were to identify and respond to family violence, what policies, procedures and training were being used, and what support staff had to identify and respond to family violence.

The Department of Education continues to support all Victorian Respectful Relationships schools to implement and embed Respectful Relationships, which is a primary prevention of family violence initiative. It supports schools to promote and model respect, positive attitudes and behaviours, and teaches students how to build healthy relationships, resilience and confidence. As at 30 June 2022, a total of 1,951 Victorian government, Catholic and independent schools are signed on to the Respectful Relationships initiative.

The Department of Education’s Respectful Relationships area staff provide on-the-ground support to schools, including Project Leads to guide implementation and Liaison Officers to support schools to identify and respond to disclosures of family violence, and to implement FVISS and MARAM. The Department of Education engaged Safe and Equal to update the Identifying and Responding to Disclosures of Family Violence training for the Department of Education’s Respectful Relationships workforce, to align with CISS, FVISS and MARAM (see Chapter 8).

Department of Families, Fairness and Housing

With responsibility for multiple workforces prescribed under MARAM, the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing has continued to review the frameworks, guidelines and tools that are required to be updated, to align to MARAM to support consistent and collaborative practice.

The progress made in 2021–22 included:

- The Service Provision Framework: Complex Needs sets out the service model, operational processes and decision-making points for the development and implementation of 2 complex needs services – the Multiple and Complex Needs Initiative (MACNI) and Support for High-Risk Tenancies. These services are delivered collaboratively by government, ACCOs, and health and community service organisations. This workforce holds identification of MARAM Responsibilities, and the updates made to the Service Provision Framework supports MARAM-aligned practice.

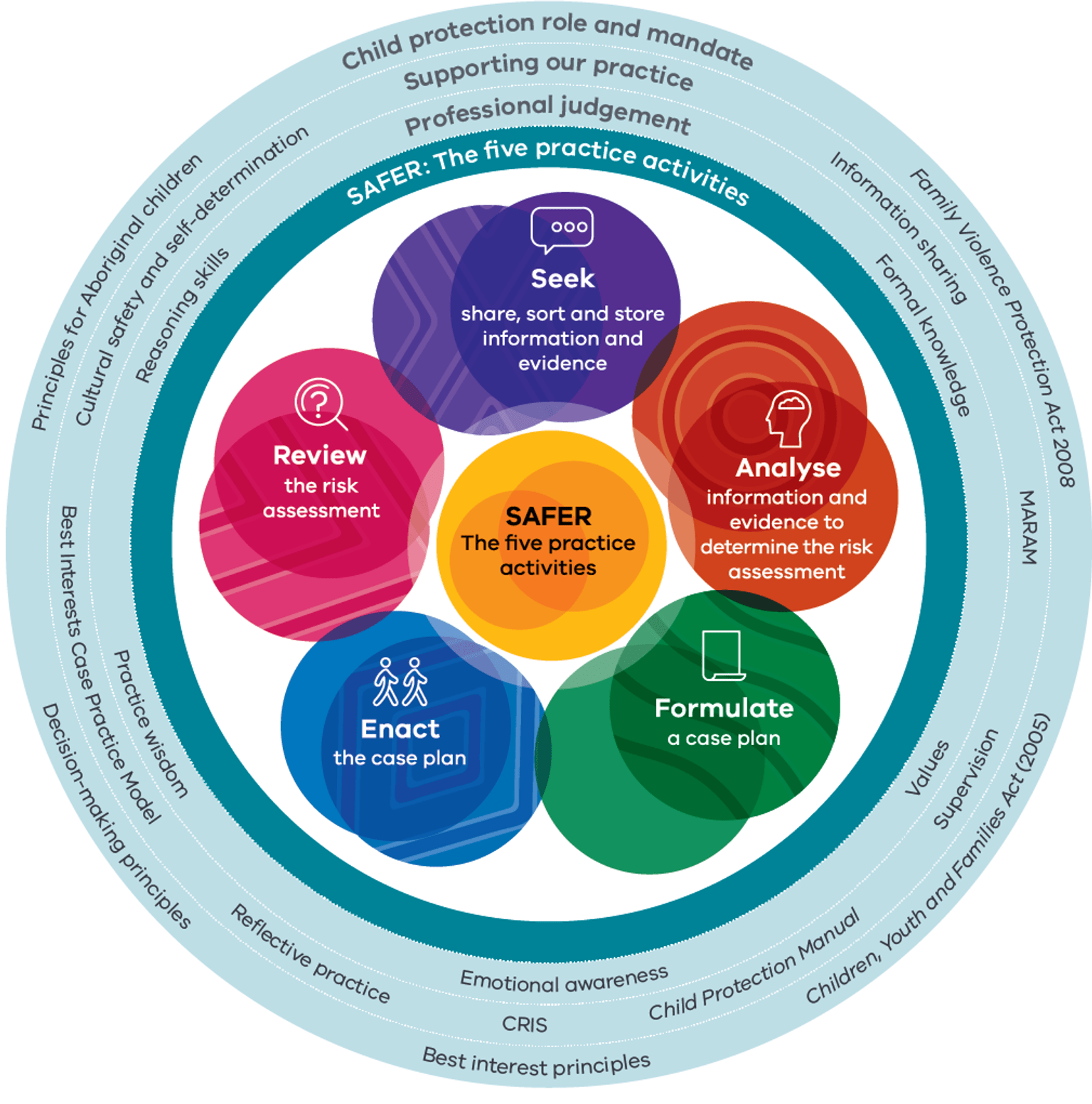

- The SAFER children framework is a risk assessment and management framework to support the work of child protection practitioners. Work was undertaken to align the SAFER children framework to MARAM, and it was launched in November 2021. As part of the alignment, MARAM risk assessment tools have been built into the Client Relationship Information System used by practitioners as part of the overall SAFER risk assessment. The outcome is that the combined tools deliver greater visibility of the intersecting risks of family violence, and support a consistent response when family violence is identified.

- MARAM Operational Guidelines for Public Housing Staff provide for the application of victim-survivor-focused MARAM practice across public housing operations. The finalisation of the guidelines was highlighted as a Department of Families, Fairness and Housing priority in the 2020–21 annual report. The guidelines set out key principles and pillars that should be embedded into procedures, service delivery and practice. They describe a shared responsibility between prescribed services and sectors to identify and respond to family violence. The aim is to build a consistent and collaborative practice by outlining MARAM practice requirements, including:

- MARAM Responsibilities

- a process for when family violence is suspected or disclosed

- basic safety planning

- information sharing

- tools to support identification and safety planning.

- The Homelessness Services Guidelines and Conditions of Funding 2014 document sets out the requirements for delivering state-funded homelessness services, particularly the essential pre-requisites that must be delivered to meet service agreement obligations. An initial MARAM updated has been included in the COVID-19 amendment to require organisational leaders to determine which MARAM Responsibilities apply to their organisations. Revised Homelessness Services Guidelines are intended to be published in 2023, which will include further content to support MARAM alignment.

- Family Safety Victoria completed significant work in 2021–22 to update the Risk Assessment and Management Panel (RAMP) Operational Requirements to ensure MARAM alignment. The requirements outline the responsibilities of RAMP Core Members under MARAM and the FVISS and CISS Schemes, and ensure consistent application across the network. The updated requirements situate RAMP’s approach to risk assessment and management to align to the MARAM framework, and extensively reference the MARAM Practice Guides, templates and tools.

- The expansion of the Central Information Point (CIP) to RAMPs was undertaken as a phased rollout from 2020, which was completed within the 2021–22 financial year. RAMP access to the CIP is part of the Royal Commission’s recommendation to establish the CIP[14]. RAMP coordinators who have completed CIP training have provided consistent feedback on the positive impact of the CIP expansion, and that it supports a consistent and collaborative approach to responding to high-risk cases.

Department of Health

A dedicated team within the Department of Health is responsible for supporting program areas and peak bodies to identify and update policies and guidelines. In 2021–22, achievements to support consistent and collaborative practice included:

- Mental Health and Alcohol and Other Drugs – Approximately 40 Specialist family violence advisors are established in each of the 17 department areas to support alcohol and other drug and mental health services. The Department of Health led the revision of the Specialist Family Violence Advisor guidelines, which outline specific responsibilities on MARAM implementation.

- Hospitals – In May 2022, SHRFV released a new resource to support hospitals to undertake workforce mapping for working with adults who use family violence.

- Ambulance services – Ambulance Victoria has developed a range of tailored family violence resources, and taken actions to support consistent and collaborative practice, including:

- contextualisation of the MARAM Brief Assessment Tool for use by paramedics in home and community settings

- working closely with The Orange Door to support effective statewide referrals and information sharing, as well as supporting paramedics to make consistent referrals to patients when not transported

- development and implementation of systems and day-to-day operations to support the FVISS and CISS

- audit of electronic patient record software capabilities against MARAM requirements with recommendations for technical changes required.

- Health workforces – the Department of Health has developed resources for all health services to support healthcare workers who are experiencing family violence. This includes a guide to developing a family violence and workforce policy, and a guide to managers on how to support staff.

Department of Justice and Community Safety

Throughout 2021–22, the Department of Justice and Community Safety continued to update policies, procedures, and practice guidance to support a broad range of workforces, including:

- CJS has been able to progress several actions to build consistent and collaborative practice, such as:

- content from the Managing Family Violence in Community Corrections Services Practice Guideline that has been merged into other existing practice guidelines, which reflects a move to family violence being ‘business as usual’. There are now family violence processes embedded across 17 practice guidelines in addition to a standalone document

- the Managing Family Violence Incidents in Prisons Guideline has been amended to include The Orange Door as a resource option and updated references to specific family violence offences.

- the CJS Family Violence Flag Project aims to improve the identification of victim survivors and persons using family violence in the CJS information management systems. In this reporting period, the information technology (IT) solution has been designed and approved, and work has progressed towards commencement of the build of the IT solution.

- the Women’s Prison System is assessing all operational policies and procedures to embed a trauma-informed approach. To date, 24 Local Operation Procedures have been reviewed using the Trauma Impact Assessment.

- Justice Health has developed a new resource to support FVISS and CISS awareness within its Information Sharing Entities and Risk Assessment Entities, which includes health information-sharing processes and how to access Justice Health services. This has resulted in a 61 per cent increase in requests for information under FVISS this reporting year, demonstrating a significant increase in collaborative practice.

-

There is ongoing development of the Family Violence Practice Manual and the Helpline Standard Operating Procedures that provide guidance and direction to the Victims of Crime Helpline staff. They ensure staff understand MARAM and their responsibilities in supporting male victims of family violence. The helpline also undertook updates to the Helpline Client Relationship Management database for increased functionality to enhance triage practices currently in place to ensure L17s are prioritised, based on victim status and risk.

-

Consumer Affairs Victoria has developed a Family Violence Information Sharing Practice Toolkit, building on resources and training. The toolkit addresses gaps in practice knowledge, particularly knowing what to share, when and with whom, to support a consistent approach to information sharing for financial counsellors and Tenancy Assistance and Advocacy Program (TAAP) workers.

-

The Dispute Settlement Centre of Victoria is in the process of drafting new procedures that will assist staff with identifying clients who may be experiencing family violence.

-

Youth Justice worked collaboratively with Victoria Police and the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing towards improved, systematic information-sharing processes to inform family violence risk assessment, planning and management of young people under Youth Justice supervision. During this reporting period, Youth Justice was granted access to the L17 (police) portal to allow timely access to referral information, to inform family violence risk assessment and management.

| TAAP reflection |

|

‘Due to our external partnerships with Specialist Family Violence Services, our TAAP team regularly receives direct warm referrals. These are received directly by our TAAP workers and are always given our highest priority. Clients are contacted almost immediately upon receipt of referral. Due to our professional relationships with family violence organisations and VCAT, where there are impending VCAT hearings these matters are expedited. Often these matters entail complex family violence and assistance with removal from leases and apportionment of debts and damage caused to properties because of family violence.’ |

| Financial counsellor reflection |

|

‘A client answered ‘no’ when asked at intake if she was experiencing family violence. Going over the MARAM questions in the first appointment revealed she was fearful of her daughter when she stayed over and took drugs with her friends. Some clients do not like to open up too much during the intake, so these questions are an important opportunity to explore any concerns. She did not see herself as experiencing family violence until we went through the assessment. I was able to develop a safety plan, apply for a Flexible Support Package and negotiate debts due to the family violence. The MARAM FV Risk Assessment itself is easy to navigate and I find it flows well. It is extremely vital in not only identifying the presence of FV but also the assessment of risk and development of a safety plan.’ Mallee Family Care |

The courts

With all MCV staff trained in affected family member MARAM practice guidance and tools completed, focus has shifted to additional activities to strengthen consistent and collaborative practice. Work undertaken in 2021–22 included:

- The Pre-Court Engagement Initiative was introduced by MCV in the 2020–21 financial year to support court users through early engagement and referrals to legal and support services. The initiative has strong engagement and currently supports 7 courts. This has resulted in over 2,500 referrals to MCV’s family violence practitioners.

- Dedicated practitioners – MCV has Umalek Balit (a dedicated Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander family violence support program) and an LGBTIQA+ family violence practitioner service. Since October 2021, the Pre-Court Engagement Initiative facilitated 187 referrals to Umalek Balit practitioners and 268 referrals to LGBTIQA+ practitioners.

Victoria Police

Victoria Police has undertaken further updates to the Victoria Police Manual and Family Violence Practice Guides by way of continuous improvement in consistent and collaborative practice. The changes include:

- a new Police Manual addressing family violence involving Victoria Police employees. This covers incident response through to prosecution, application of discipline procedures, and management responsibilities for victim survivors and persons using family violence

- updated Family Violence Practice Guides, including:

- personal property conditions for Family Violence Intervention Orders that direct the return of essential property, noting exclusion conditions that enable a return to the residence to collect personal belongings in the presence of police

- taking reports of family violence by telephone, which allows prompt recording of family violence incidents where it is determined that there is no risk of harm to any party. This guide assists members to make evidence-based decisions to provide a more accurate assessment of a current family violence episode, with consideration to historical episodes

- standalone Practice Guides for priority community and diverse community responses, which are now comprehensive, standalone documents to ensure increased understanding, rather than a previous consolidated version.

[14] Recommendation 7 of the Royal Commission into family violence recommended that the Victorian Government establish a secure Central Information Point, with a summary of the information being available to RAMPS.

Information sharing

Information sharing is an indicator of consistent and collaborative practice. Where instances of information sharing are increasing, it suggests an increase in family violence being identified and practitioner confidence in the benefits of multi-agency collaboration.

As the MARAM reforms have progressed in maturity, information-sharing demand has increased considerably across the sector, when compared to the 2020–21 period. It also reflects the prescription of additional workforces in April 2021, and the impact of continued training and capability-building activities.

It should be noted that there is no legal requirement to collect FVISS and CISS data. Data that is available is from departments with the ability to collect central information. For those that do, this section outlines information-sharing demand and activity in the 2021–22 reporting period.

The courts

In 2021–22, the courts experienced significant growth in demand and received 34,326 requests for information, which is a 20 per cent increase from the previous financial year.

The Department of Families, Fairness and Housing’s Child Protection continues to be the primary source of information-sharing requests, with a total of 12,744 requests made, accounting for 37 per cent of all requests to the courts.

The number of requests received from The Orange Door network has more than doubled, with 11,938 requests received, compared to 5,475 requests in 2020–21. The Orange Door network accounted for 35 per cent of the total number of requests received by the courts.

A further 9,644 or 28 per cent of requests were received from specialist family violence service providers, including Safe Steps and other community-based organisations.

Table 2: The courts’ information-sharing activity 2021–22

| Type of activity | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Total financial year | Total since February 2018 |

| Requests | 8,007 | 7,897 | 8,575 | 9,847 | 34,326 | 91,295 |

Victoria Police

In 2021, Victoria Police introduced a new record-keeping solution for the FVISS and CISS to improve data capture, workflow processes and the output shared with other Information Sharing Entities. This is indicated in Table 3, with an increase in the number of categories now available, which has allowed for more precise data to be available for business and reporting needs.

The number of requests in this reporting period have increased significantly with 1,119 additional requests received, compared to the previous year, an increase of 20 per cent over the previous year.

Table 3: Victoria Police’s information-sharing activity 2021–22

| Type of activity | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Total financial year |

| Requests received | 1,611 | 1,533 | 1,682 | 1,794 | 6,620 |

| Shared | 1,576 | 1,508 | 1,489 | 1,688 | 6,241 |

| Not shared | 35 | 25 | 193 | 126 | 379 |

| Voluntary | 113 | 105 | 79 | 62 | 359 |

Department of Justice and Community Safety – Corrections Victoria

Corrections Victoria saw its FVISS requests double in 2021–22 compared to 2020-21. The increase is likely due to the addition of health and education services to the reforms in April 2021, and additional information requests directly to CV from The Orange Door.

To meet the increased demand, Corrections Victoria has provided additional staffing resources.

Table 4: Corrections Victoria’s information-sharing activity 2021–22

| Type of activity | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Total financial year |

| Number of requests responded to | 1,012 | 1,413 | 1,518 | 2,086 | 6,029 |

| Number of requests not yet released* | 74 | 87 | 112 | 186 | 459 |

*Common reasons why information was declined in some instances: where the identity of the perpetrator could not be confirmed based on the initial information provided; further information was required for protection purposes; exclusion; no consent; or the entity requesting the information was not an information-sharing entity.

Department of Families, Fairness and Housing – Child Protection

In the 2021–22 financial year, the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing received a total of 3,652 requests for information (noting this relates to closed Child Protection cases only). The most frequent requesting Information Sharing Entities were Victoria Police, Specialist Family Violence Services and hospitals. Information-sharing requests consistently increased quarter on quarter in the financial year, with requests made under the FVISS increasing over 50 per cent between quarter one and quarter 4.

Table 6: Information-sharing requests not shared 2021–22

| Authorising scheme | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Total |

| FVISS only | 113 | 136 | 235 | 231 | 715 |

| CISS only | 159 | 250 | 355 | 235 | 999 |

| FVISS and CISS | 519 | 336 | 220 | 353 | 1,428 |

| Other | 19 | 5 | 216 | 270 | 510 |

| Total | 810 | 727 | 1,026 | 1,089 | 3,652 |

Table 6: Information-sharing requests declined 2021–22

|

Authorising scheme |

Q3 | Q4 | Total year |

| FVISS only | 9 | 24 | 33 |

| CISS only | 12 | 12 | 24 |

| FVISS and CISS | 5 | 28 | 43 |

| Other | 90 | 138 | 228 |

| Total | 116 | 212 | 328 |

| Authorising scheme | Q3 | Q4 | Total year |

| FVISS only | 36 | 6 | 42 |

| CISS only | 25 | 0 | 25 |

| FVISS and CISS | N/A | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 61 | 6 | 67 |

Data for requests that were declined and for information that was proactively shared was not captured as independent values until the third and fourth quarter (January to June 2022). Requests were declined because they did not meet the FVISS or CISS thresholds, or the request lacked sufficient detail to enable the request to be assessed.

Table 7 shows that the team proactively shared risk-relevant information 67 times in the last 6 months of the financial year.

Section C: Sectors as lead

In 2021–22, there has been an increase in funded sector capacity-building participants delivering Communities of Practice webinars and workshops. These have included:

- The Council to Homeless Persons and Elizabeth Morgan House partnered to develop an animated case study about sharing risk-relevant information in a culturally safe way.

- The CFECFW, NTV, and Safe and Equal co-facilitated a quarterly Collaborative Sectors Network. This brings together organisations across the sectors to share lessons learned. It promotes consistent and collaborative practice, and enables continuous improvement.

- VACCA consulted and supported several smaller ACCOs to strengthen networking relationships and share resources to support their alignment to MARAM and information-sharing operations. This consultative approach led to the establishment of a Housing Working Group to support collaboration between VACCA, Aboriginal Housing Victoria and Council to Homeless Persons.

- SHRFV statewide leads at Bendigo Health and The Royal Women’s Hospital facilitate Communities of Practice every 6 to 8 weeks. The Communities of Practice enable SHRFV staff members to provide formal and informal feedback about lessons learned in implementation, to support consistent and collaborative practice across the state. In addition to the Communities of Practice, SHRFV members have access to an online platform where they regularly share learnings, knowledge and support.

- The TAAP team has established ongoing working relationships with the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (VCAT) Family Violence Coordinator. The VCAT now regularly refers matters to TAAP.

- The Financial Counselling Program co-delivered workshops with Gamblers Help to a service with a Men’s Behaviour Change Program. This has promoted collaboration, service awareness and cross referrals. The workshops will be delivered annually.

- ECA developed a MARAM toolkit with tools, resources, policies, procedures and guidance to further contextualise the reforms for this sector. The toolkit was piloted in 5 early childhood services.

| Elizabeth Morgan House case study |

|

Sharee, an Aboriginal woman, has been in a two-year relationship with Mark, a non-Aboriginal man, who has been violent to her on numerous occasions. Although Sharee left Mark a few times, she returned as she had nowhere else to live. Sharee agreed to a MARAM risk assessment and to information-sharing requests about Mark. The FVISS request came back from police with the following information: Mark has been violent against 3 previous partners and has a history of breaching Family Violence Intervention Orders. Mark has been charged with several violent assaults to strangers and been convicted of aggravated assaults with weapons such a knife and a bottle. Mark also has a recent charge for possession of amphetamine. Further information-sharing requests reveal Mark is on a six-month Community Corrections Order, is linked into a Behaviour Change Group, and sees an alcohol and other drug worker. Adele arranges a PIVA (Person using violence in view and accountable) meeting of the professionals supporting Mark and shares the relevant parts of the risk assessment to enhance safety planning. The alcohol and other drug worker advises that Mark has increased his substance use in recent weeks, uses ice regularly and is self-medicating with downers to sleep and is often angry – blaming Sharee for making him angry. The Men’s Behaviour Change worker shares that Mark has stated that he would kill himself if Sharee left him, and that they have created a plan with Mark for when he feels this way. Mark has breached his Community Corrections Order by failing to submit urine screens and has returned a positive result for methamphetamines for the screens he has submitted. There is also a future hearing where he may get a custodial sentence. The information supports Adele to update Sharee’s MARAM risk assessment and informs her determination of the level of risk and safety planning. *Not their real names |

The Elizabeth Morgan House case study demonstrates the use of:

- the MARAM Risk Assessment

- FVISS

- MARAM Multi-Agency Practice

- information sharing

- an intersectional approach

- keeping the perpetrator in view and accountable

- respecting the victim survivor’s agency

- trauma-informed practice.

Summary of progress

Consistent practice, where services all safely identify and respond to family violence in their contexts, is fundamental to ensuring no wrong door for victim survivors. Continued progress in updating workforce-specific practice guidance is a key step towards consistent practice. The increased use of MARAM online tools also demonstrates a consistent practice approach.

Collaborative practice builds on consistent practice, as workforces from different disciplines can communicate, based on a shared understanding of family violence. Information-sharing data illustrates an increased connection between workforces, and a willingness to request and share information using the available schemes.

As MARAM continues to be embedded, it is anticipated that consistent and collaborative practice will strengthen the systemic response to family violence.

Updated