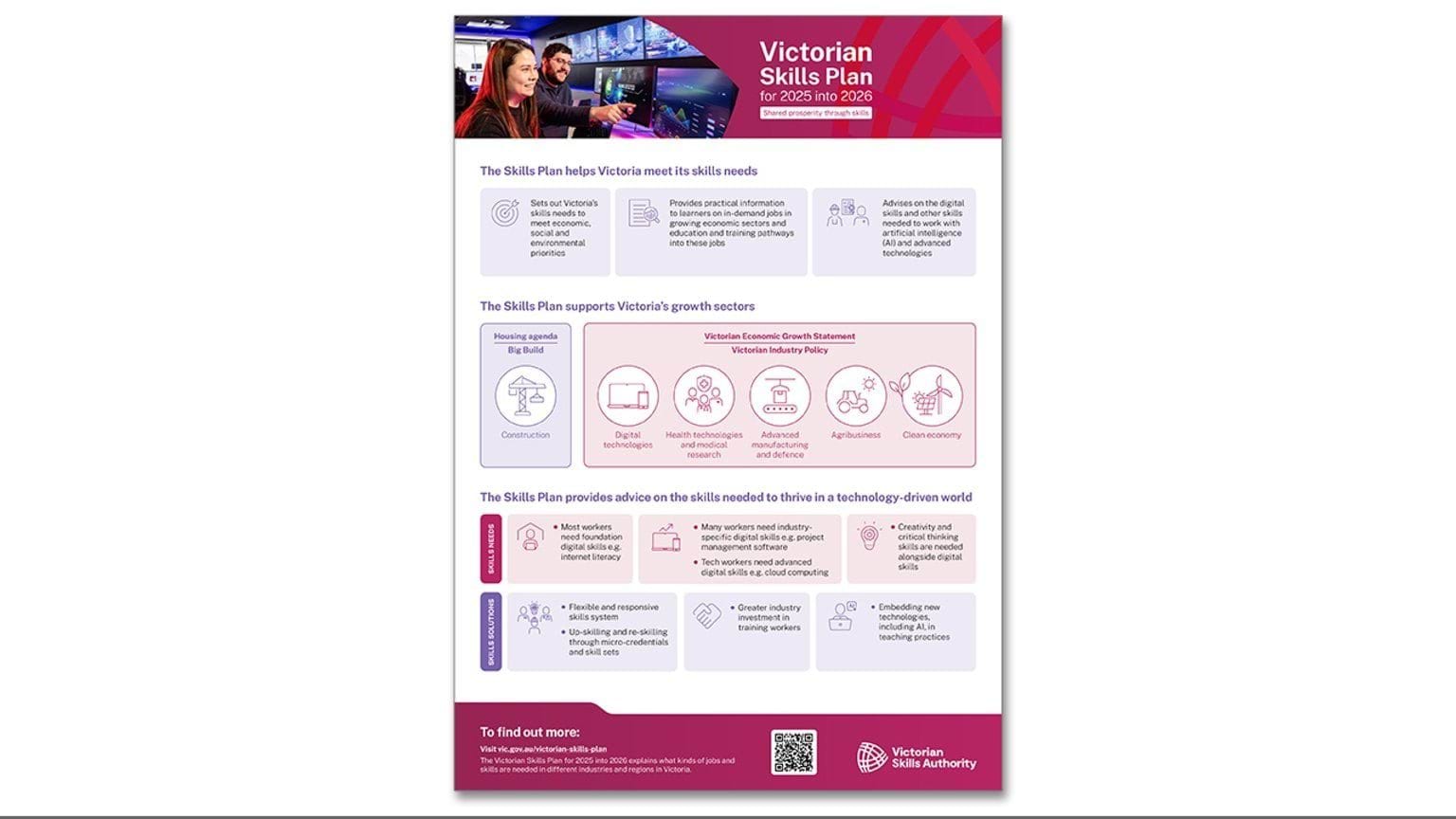

The Victorian Skills Plan underpins Victoria’s skills roadmap, to help TAFEs and other training providers plan for courses, industries ensure they have the workers they need, and Victorians with education and training pathway choices for success in work and life.

Victorian Skills Plan for 2025 into 2026

Read the fourth Victorian Skills Plan.

An accessible version of the Victorian Skills Plan for 2025 into 2026 will be available soon. If you require this in the interim, please contact vsa.enquiries@ecodev.vic.gov.au

Find out more about the Victorian Skills Plan for 2025 into 2026

Previous Victorian Skills Plans

Updated