- Published by:

- Department of Families, Fairness and Housing

- Date:

- 14 Apr 2022

A message from the Minister for Prevention of Family Violence

Aboriginal acknowledgement

We proudly acknowledge Victoria’s Aboriginal communities and their ongoing strength in practising the world’s oldest living culture. We acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the lands and waters on which we live, work, learn and play, and pay our respects to their Elders past and present.

We acknowledge the ongoing leadership role of the Aboriginal community in addressing and preventing family violence. We join with First Peoples to eliminate family violence from all communities.

Acknowledgment of victim survivors of family violence

We pay our respects to victims and victim survivors of family violence and violence against women. We acknowledge their resilience and courage. They remain at the forefront of our work.

In 2015, the Victorian Government established the Royal Commission into Family Violence following a series of family violence-related deaths in Victoria. In its final report, the Royal Commission set out the case for focused, coordinated leadership backed by new investment and approaches. Its recommendations aim to prevent family violence, support victim survivors and hold perpetrators to account.

The government committed to implementing all 227 recommendations, setting out its plan in Ending family violence: Victoria’s plan for change (the 10-year plan). The plan’s goal is to establish a nation-leading family violence system. It also seeks to create a Victoria where all people live free from family violence, and where women and men are treated equally and respectfully.

In 2022, only 23 of the 227 Royal Commission recommendations remain to be implemented.

This report is part of the Victorian Government’s annual reporting commitments on the progress and impact of the family violence reform. It uses the Family Violence Reform Rolling Action Plan 2020–2023 (the Rolling Action Plan) and the Family Violence Outcomes Framework (the Outcomes Framework) to do this.

This website, which will be updated annually, helps ensure accountability to the community for the commitments made in the 10-year plan and the impact of the reform.

Momentum for this once-in-a-generation reform cannot be lost.

Overview

Reform activity across the Family Violence Outcomes Framework

The Royal Commission into Family Violence revealed the devastating prevalence and impact of family violence across Victoria. It cuts lives short, inflicts unspeakable trauma, creates cycles of intergenerational trauma and violence1, and costs more than $5.3 billion a year2.

Ending family violence in Victoria is a huge challenge. It requires a holistic, joined-up approach, sustained over a generation. We must continue to work together to prevent and respond to all forms of family violence. This work is informed by victim survivors, and it takes place in our schools and hospitals, our courts and our community centres, across specialist family violence workforces.

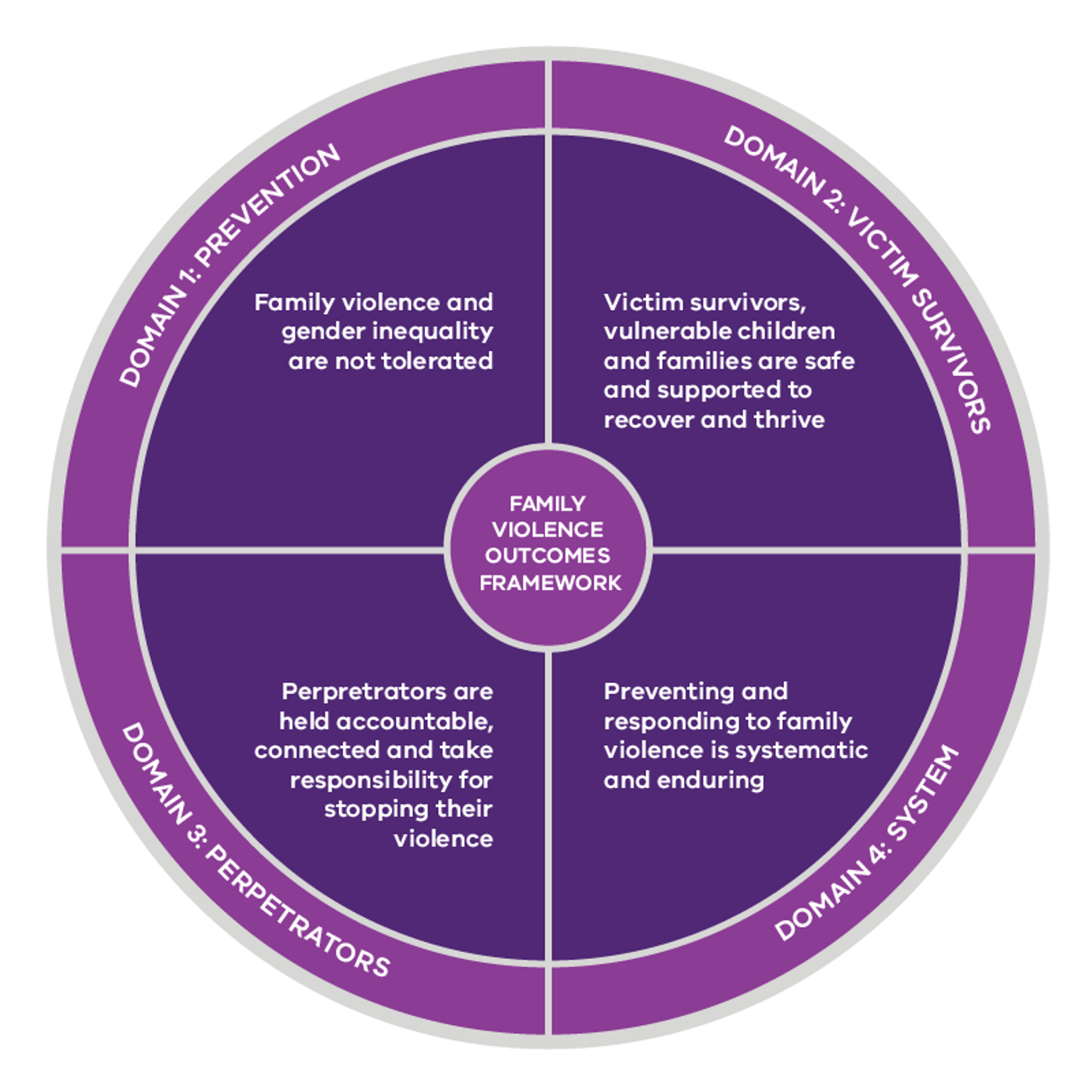

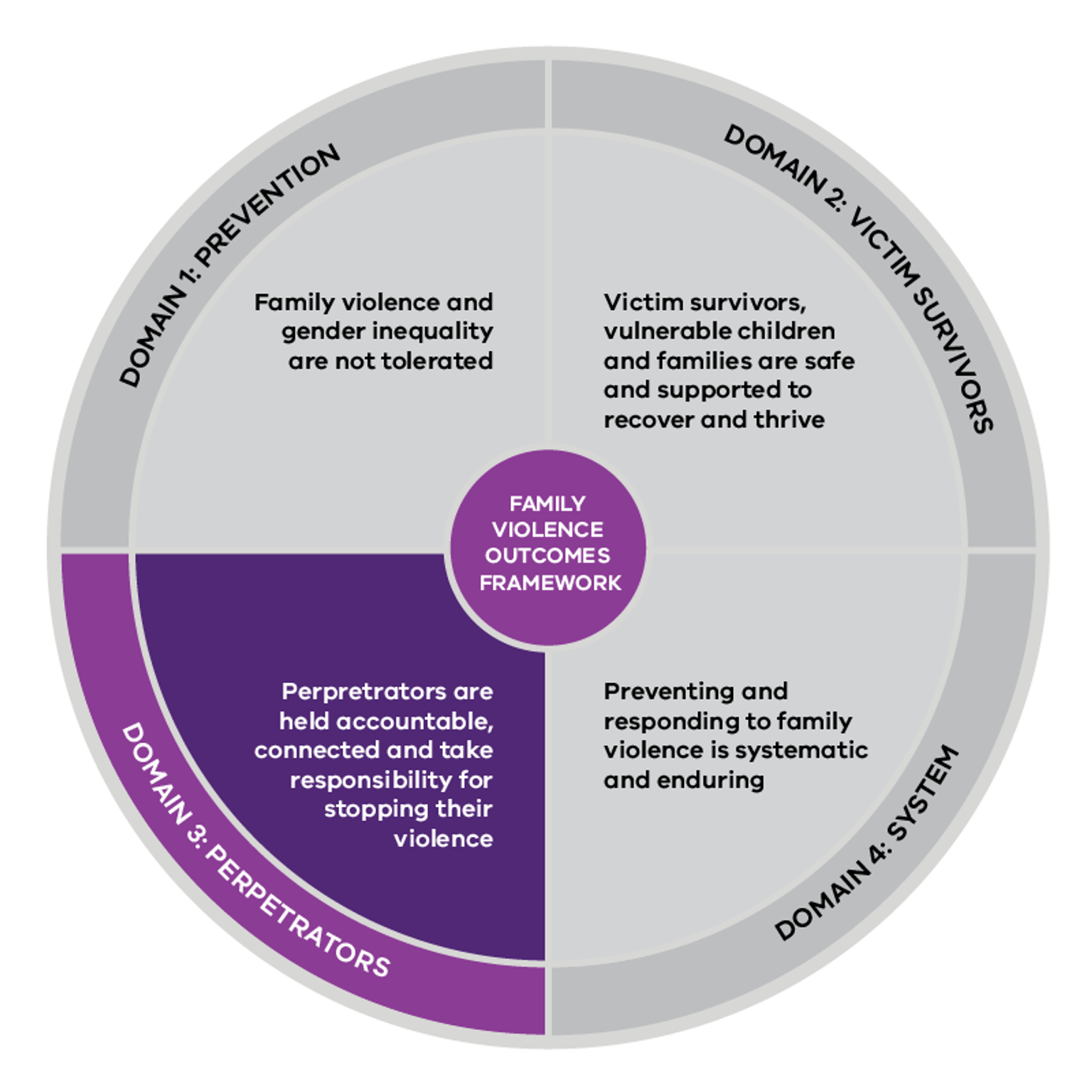

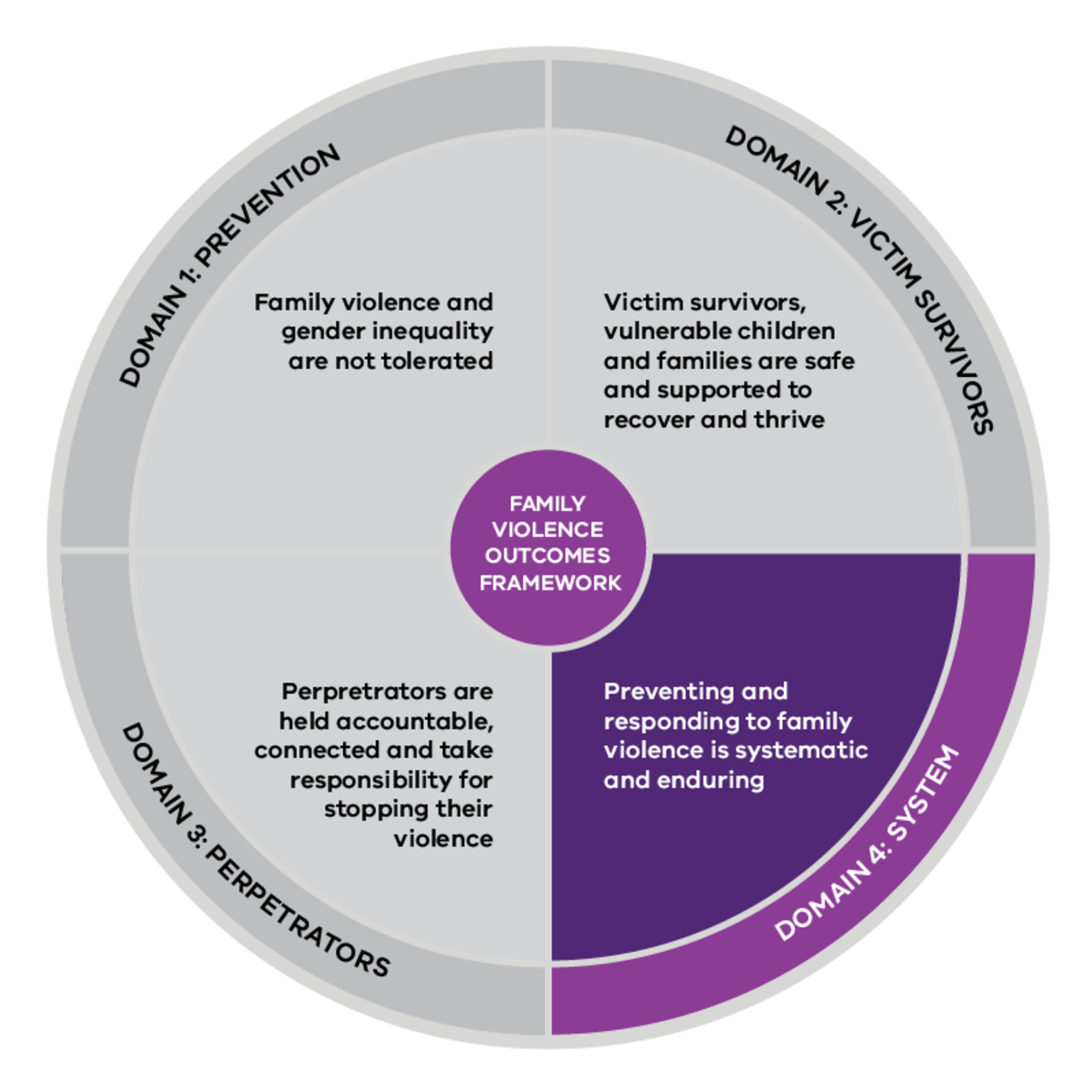

The Family Violence Outcomes Framework provides a common set of goals that unite this diverse group of people and organisations. The Outcomes Framework has four domains:

- Prevention – family violence and gender inequality are not tolerated.

- Victim survivors – victim survivors, vulnerable children and families are safe and supported to recover and thrive.

- Perpetrators – perpetrators are held accountable, connected and take responsibility for stopping their violence.

- System – preventing and responding to family violence is systemic and enduring.

Each year, this website will be updated to reflect progress against the Family Violence Outcomes Framework and against the Family Violence Reform Rolling Action Plan 2020-2023.

How we are tracking

To understand how we are tracking, we must first understand the intent of the Royal Commission recommendations. These lay the foundation for short, medium and long-term change.

The Royal Commission noted that its task was to make practical recommendations on the most effective ways to:

- prevent family violence

- improve early intervention to identify and protect those at risk

- support victims – particularly women and children – and address the impacts of violence on them

- make perpetrators accountable

- develop and refine systemic responses to family violence – including in the legal system and by police, corrections, child protection, legal and family violence support services

- better coordinate community and government responses to family violence

- evaluate and measure the success of strategies, frameworks, policies, programs and services introduced to put a stop to family violence.

Having a theory of change is vital to this work and informs what we do. We understand that to see change occurring we must first improve the system that supports our prevention of, responses to and understanding of family violence.

This is why we are:

- developing a coordinated family violence system

- investing in prevention, early intervention and response

- prioritising evaluation, learning and continuous improvement.

This approach will support victim survivors and hold perpetrators to account, with the goal of ending family violence in Victoria.

This website combines the progress report on the Rolling Action Plan with the latest data on the Outcomes Framework. Our assumption is that if we implement the Rolling Action Plan, we will see changes occurring that support the achievement of our outcomes.

The final 23 of the 227 recommendations of the Royal Commission are on track to be implemented in 2022.

With these recommendations in place, the foundations of our system are strong. However, our efforts to build the system continue, as does our long-term prevention work to change the attitudes, behaviours and power imbalances that lead to family violence.

While it is still early in this generational reform, we remain committed to sharing our progress and challenges.

Significant progress has been made

The Rolling Action Plan 2020–2023 outlines our focus for this phase of the reform. This report shows progress against the actions committed to in the Rolling Action Plan, including:

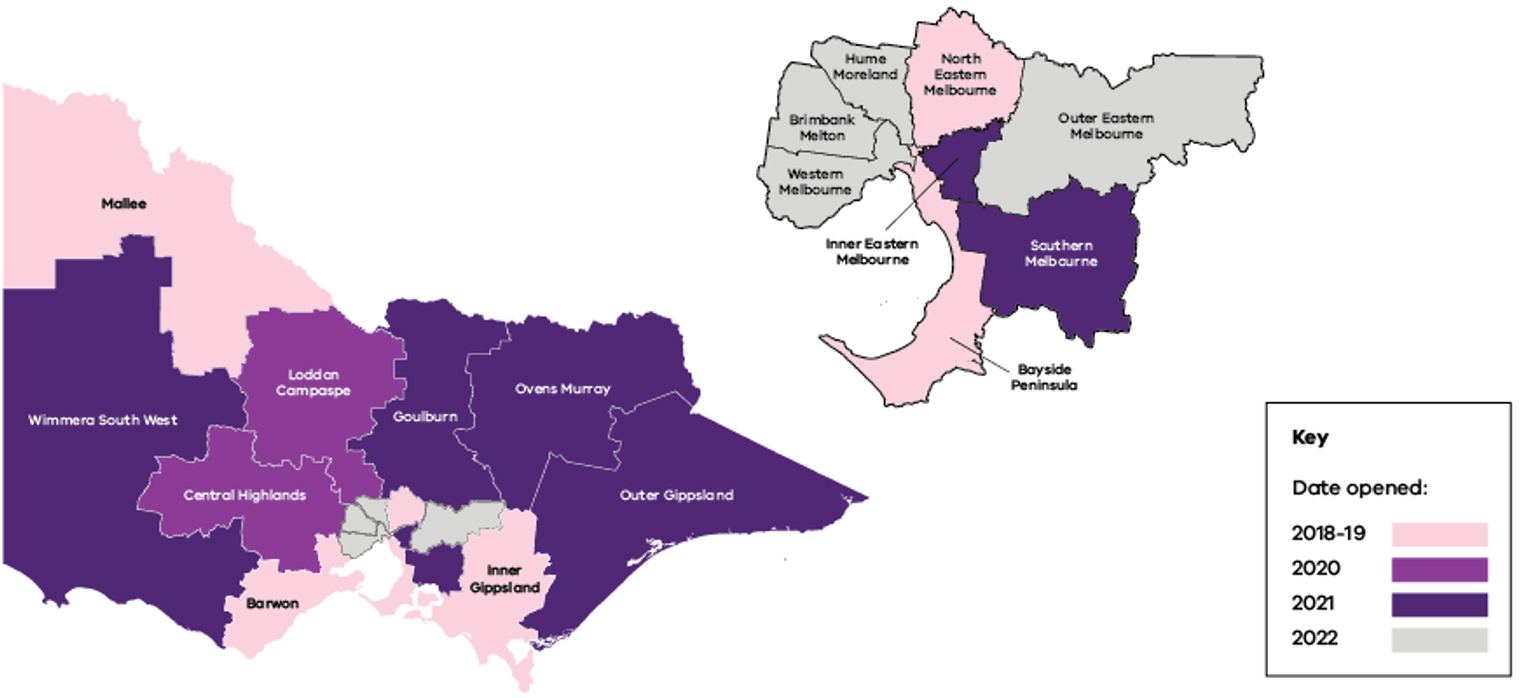

- the continued establishment of The Orange Door network, a free service for adults, children and young people experiencing family violence, where they can access the support they need from a range of specialist services. Two new Orange Door sites opened in 2020 and another six in 2021. Since its commencement in May 2018, The Orange Door has received more than 200,000 people, including more than 80,000 children (as at February 2022).

- the establishment of another three Specialist Family Violence Courts, with five now in operation and plans for another nine across Victoria

- the construction of 349 new homes in line with the Big Housing Build and nine new core and cluster refuges completed and operational by October 2021

- the continued implementation and training for the Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management (MARAM) Framework to ensure an effective and consistent approach to assessing and managing the risk of family violence. With the roll out of Phase 2 of the MARAM over 370,000 practitioners (as at April 2021) are now prescribed from organisations across the health, education, justice and social service system

- the development of primary prevention practice across key settings including local government, TAFEs, universities and perinatal settings

- investment in innovative prevention initiatives led by diverse communities, including Aboriginal-led organisations, multicultural and faith-based organisations and other community groups in Victoria

- more than 1,950 government, Catholic and independent schools signing on to a whole-school approach to Respectful Relationships education, and more than 35,000 school staff and 3,500 early childhood educators participating in Respectful Relationships professional learning

- high-impact public campaigns conducted by Respect Victoria to raise awareness of family violence and how to prevent it. Evaluation of these campaigns demonstrated a high level of community recognition and understanding of the key messages

- equipping those working in family violence services, as well as those whose work requires them to be aware of the risks of family violence, with the training they need to do their jobs effectively. Workforce census data indicates that at least half of those who responded from specialist family violence services and from across the primary prevention workforce felt very or extremely confident in their level of training and experience to complete their role.

Adapting to the COVID-19 pandemic

Some of our activities have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. During this time, our focus was on supporting those most in need, given the heightened risk of family violence. To limit the impact of the pandemic, we have:

- provided $20 million for short-term accommodation for victim survivors who did not feel safe isolating or recovering from COVID-19 at home

- provided $20.2 million to help Victorian family violence services meet the expected increase in demand during the coronavirus pandemic and provide critical help for victim-survivors

- implemented the Multicultural COVID-19 Family Violence Program, which provided one-off funding to 20 multicultural, faith-based and ethno-specific organisations to help raise awareness of the drivers of family violence and support early intervention activities

- continued to provide crisis accommodation and all family violence, sexual assault and The Orange Door services. We worked with the sector to strengthen these services during the pandemic

- launched Operation Ribbon, where police proactively reached out to victim survivors to check on their safety and wellbeing, and to perpetrators to monitor their behaviour and keep them in view

- established the Men’s Accommodation and Counselling Service for men who use violence, providing crisis accommodation, wrap-around support to address immediate concerns and link men to services to address their offending behaviour

- increased the accessibility of Men's Behaviour Change Programs by moving to online groups and one-on-one engagement to keep men who use violence in view. We also continued to provide support when face-to-face groups were suspended.

Understanding our impact

With the foundational elements of the reform in now in place, we can begin to use the Outcomes Framework to demonstrate our impact.

We have strong data across our family violence and justice system that tells a story about the incidence of family violence and use of services.

However, we know we have more work to do to strengthen the consistency of data across government and the family violence sector, so that it gives a more comprehensive and nuanced picture of the impact of our reforms.

The data that has informed this first report is just the starting point. We will update this data annually as we continue to work with stakeholders to improve its availability and quality. Through this process, we will identify and develop new measures. We will also apply an increasingly sophisticated analysis to existing measures to help us better understand the impact of the reforms.

Our immediate focus is on linking existing datasets. This will help us better understand the different points of contact and engagement victim survivors and perpetrators have across the service system and how this affects their outcomes.

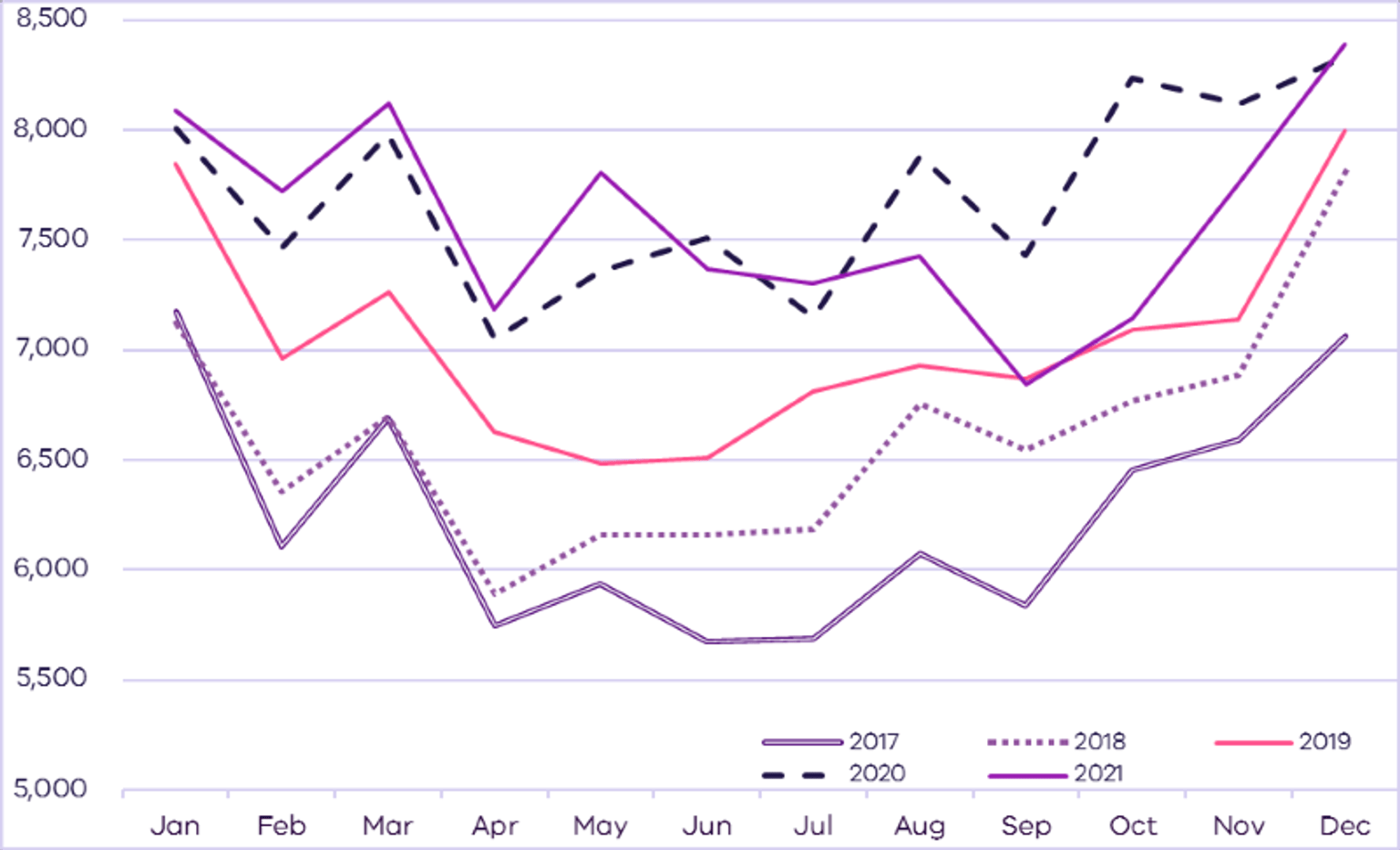

Family violence incidents recorded by police are rising in line with our expectations

There has been a general trend of increased reporting of family violence incidents to police since 2016. This is in line with what we expected to see at this stage of our 10-year plan. The COVID-19 pandemic has also likely impacted the significantly higher numbers of incidents in 2020.

There were 91,144 family violence incidents in 2021, a 1.5 per cent reduction on 2020 (92,513). Despite this modest decrease, the number of incidents in 2021 was still 7.8 per cent higher than in 2019.

Our investment and reforms have:

- helped raise awareness of family violence across the Victorian community

- made services more accessible to those who need them

- supported victim survivors to report violence committed against them.

These year-on-year increases are likely to continue in these early stages of changing the way we address family violence. This is because community awareness is growing, women are beginning to feel safer and more confident in support systems, and, importantly, we are improving justice responses for victim survivors and hold perpetrators to account.

Looking ahead

At just over halfway in the implementation the 10-year plan, more than $3.5 billion has been invested to prevent family violence, support victim survivors and hold perpetrators to account.

Victorians are more aware than ever of what family violence is and the help that is available to them. Sadly, many people will still need to access that help in the years to come.

This is why we must maintain our focus and investment to realise the full intent of the Royal Commission and bring an end to family violence.

In 2022, we will continue to deliver the Rolling Action Plan and implement the remaining 23 recommendations of the Royal Commission. We will continue to be informed by the lived experiences of victim survivors. We will also apply an inclusive lens that recognises how factors such as race, age, disability, culture and gender affect people’s experience.

We will begin to implement the Free from Violence Second Action Plan and finalise the Sexual violence and harm strategy, which will respond to the Victorian Law Reform Commission’s report on Improving the justice system response to sexual offences.

We will continue to work closely with the family violence sector to ensure victim survivors and people who use violence receive more consistent, better integrated services. The goal of this work is to end the cycle of violence and minimise retraumatisation.

This will help build a family violence system that is responsive and resilient to further shocks. It will also equip us to better understand the impact of our efforts and continually strengthen them.

Notes

1 State of Victoria 2016, Royal Commission into Family Violence: Summary and recommendations, Parl Paper No 132 (2014–16). http://rcfv.archive.royalcommission.vic.gov.au/MediaLibraries/RCFamilyV…

2 KPMG 2017, ‘The Cost of Family Violence in Victoria: Summary Report’, prepared for the Department of Premier and Cabinet in Victoria.https://www.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-05/Cost-of-family-viole…

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

Like many things, the COVID-19 pandemic has had a profound impact on family violence.

We know that family violence is driven by expressions of gender inequality: the unequal distribution of power, resources and opportunities between men and women.1 Gender inequality is the outcome of and is exacerbated by rigid gender stereotypes such as men’s control of decision making.

Other factors including financial pressure, alcohol and drug abuse, mental illness and social and economic exclusion can also increase the risk or severity of family violence, but are not the underlying drivers. 1, 2

There is strong evidence that the gendered drivers and factors that exacerbate gendered violence are heightened during and following emergencies and crises, resulting in increases in violence, particularly against women.

Notes

1 Parkinson D 2017, ‘Investigating the increase in domestic violence post-disaster: An Australian case-study’, Journal of Interpersonal Violence, March 2017. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0886260517696876.

2 State of Victoria 2016, Royal Commission into Family Violence: Summary and recommendations, Parl Paper No 132 (2014–16). http://rcfv.archive.royalcommission.vic.gov.au/MediaLibraries/RCFamilyV…

3 Pfitzner N, Fitz-Gibbon K and True J 2020, Responding to the ‘shadow pandemic’: practitioner views on the nature of and responses to violence against women in Victoria, Australia during the COVID-19 restrictions. Monash Gender and Family Violence Prevention Centre, Monash University, Victoria, Australia.

4 Boxall H and Morgan A 2021, ‘Who is most at risk of physical and sexual partner violence and coercive control during the COVID-19 pandemic?’ Australian Institute of Criminology, Trends & Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice, no. 618, February 2021.

5 Boxall H and Morgan A 2020, ‘Social isolation, time spent at home, financial stress and domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic’, Australian Institute of Criminology, Trends & Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice, no. 609, October 2020.

6 Pfitzner N et al. 2020, When home becomes the workplace: family violence, practitioner wellbeing and remote service delivery during COVID‑19 restrictions, Monash Gender and Family Violence Prevention Centre, Melbourne, 20 October 2020.

Family Violence Outcomes Framework measures

Translating our vision of a Victoria free from family violence into a quantifiable set of outcomes, indicators and measures

The Family Violence Outcomes Framework (the Outcomes Framework) translates our vision of a Victoria free from Violence, outlined in our 10-year Plan, into a framework that will enable us to measure and understand the impacts of our efforts.

The Family Violence Outcomes Framework

The four domains that make up the Outcomes Framework are:

- Family violence and gender inequality are not tolerated.

- Victim survivors, vulnerable children and families, are safe and supported to recover and thrive.

- Perpetrators are held accountable, connected and take responsibility for stopping their violence.

- Preventing and responding to family violence is systemic and enduring.

Data availability and improvements

Data in this report was collected and analysed through consultation with departments and agencies across government. This included the Crime Statistics Agency, the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing, and from publicly available surveys conducted by the Australian Bureau of Statistics and Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety.

The foundational measures in this report provide a starting point.

About half of the measures in this report are Victorian crime and justice data sourced via the Crime Statistics Agency. We know family violence is far reaching and not just limited to policing (as the breadth of priorities in this website’s Rolling Action Plan section shows). As more and more parts of the reform are implemented, we can expand the measures under the Outcomes Framework, so we have a better sense of the impact our work has had on people’s lives across all parts of the reform.

To get there, we know we have more work to do to continue to strengthen the availability and consistency of data across government and the family violence sector. Although the impact of COVID-19 delayed our outcomes measurement and monitoring program in 2021, over the next few months we are working to improve data by:

- linking data sets and identifying new data sources to test new outcomes measures related to victim survivors and perpetrators

- disaggregating data for priority communities, for example Aboriginal and culturally and linguistically diverse communities

- developing a tracking system to support the collection of data relating to the outcomes of perpetrator interventions and family violence therapeutic interventions

- developing short to medium-term prevention measures to tell us how we are tracking as we work towards our long-term vision of a Victoria free from violence.

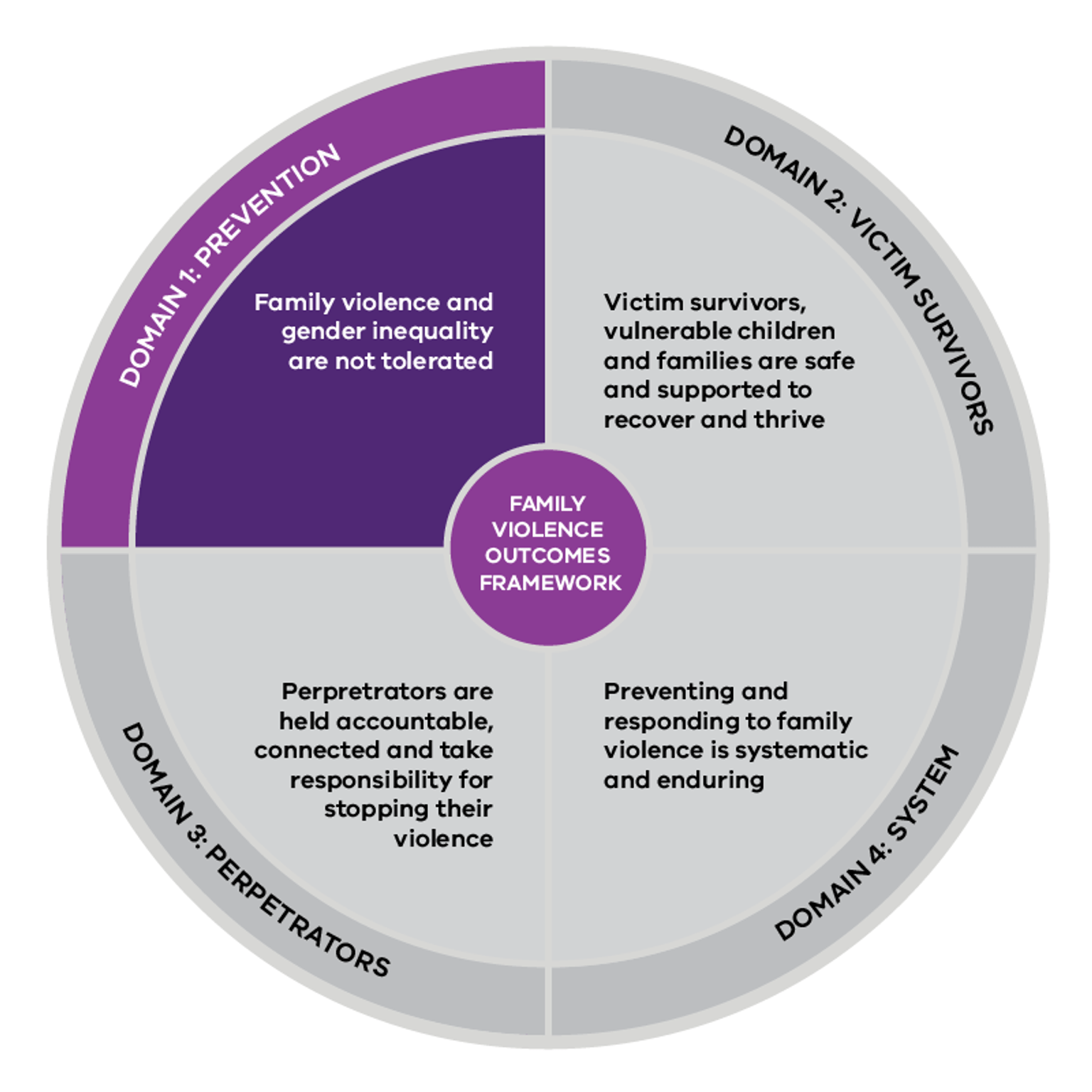

Domain 1: Prevention

Family violence and gender inequality are not tolerated

To prevent family violence and other forms of violence against women, we must challenge the underlying social norms, structures, systems, attitudes and practices that create and perpetuate gender inequality and discrimination.

We must also address the intersecting forms of discrimination and disadvantage that compound the impact of gender inequality to increase rates of violence and influence patterns of violence for diverse community groups. These forms of discrimination include racism, ableism, ageism, classism, heterosexism, homophobia and the continuing impacts of colonisation on Aboriginal people.

Effective prevention strategies will progressively reduce future prevalence of violence against women and family violence. Ending this violence at the population-level requires long-term, sustained investment over many years to achieve positive generational, cultural and attitudinal shifts in gender inequality and the gendered drivers of violence.

We can even expect to see some increase in prevalence rates for indicators of family violence. This is because as there is greater awareness of the issue, those experiencing it are more likely to recognise it, report it and seek help from response services.

Ultimately, however, our investments in prevention aim to reduce the incidence of family violence and all forms of violence against women. This will lead to new generations of Victorians growing up with changed values and behaviours in a more equal society.

We know short- and medium-term change is possible, but sustaining this change requires coordinated and mutually reinforcing activities across a wide number of sectors and settings. However, this will require adequate investment in prevention, a generational commitment to see the task through and continual refinement of the most effective prevention strategies. Only then will we begin to see a decrease in the prevalence of family violence and all forms of violence against women.

Data availability

Data for the prevention domain measures published in the baseline report in December 2020 is not yet available. This is because the COVID-19 pandemic has delayed collection and reporting for the 2020 Personal Safety Survey (conducted by the Australian Bureau of Statistics) and the National Community Attitudes Survey (undertaken by Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety). We expect data will be available in the 2023 edition of the Ending Family Violence report.

The Prevention of Family Violence Data Platform is aligned with the ‘Prevention’ domain of the Outcomes Framework. It features a wide range of data from 34 existing sources which are collected at regular intervals by a range of external organisations.

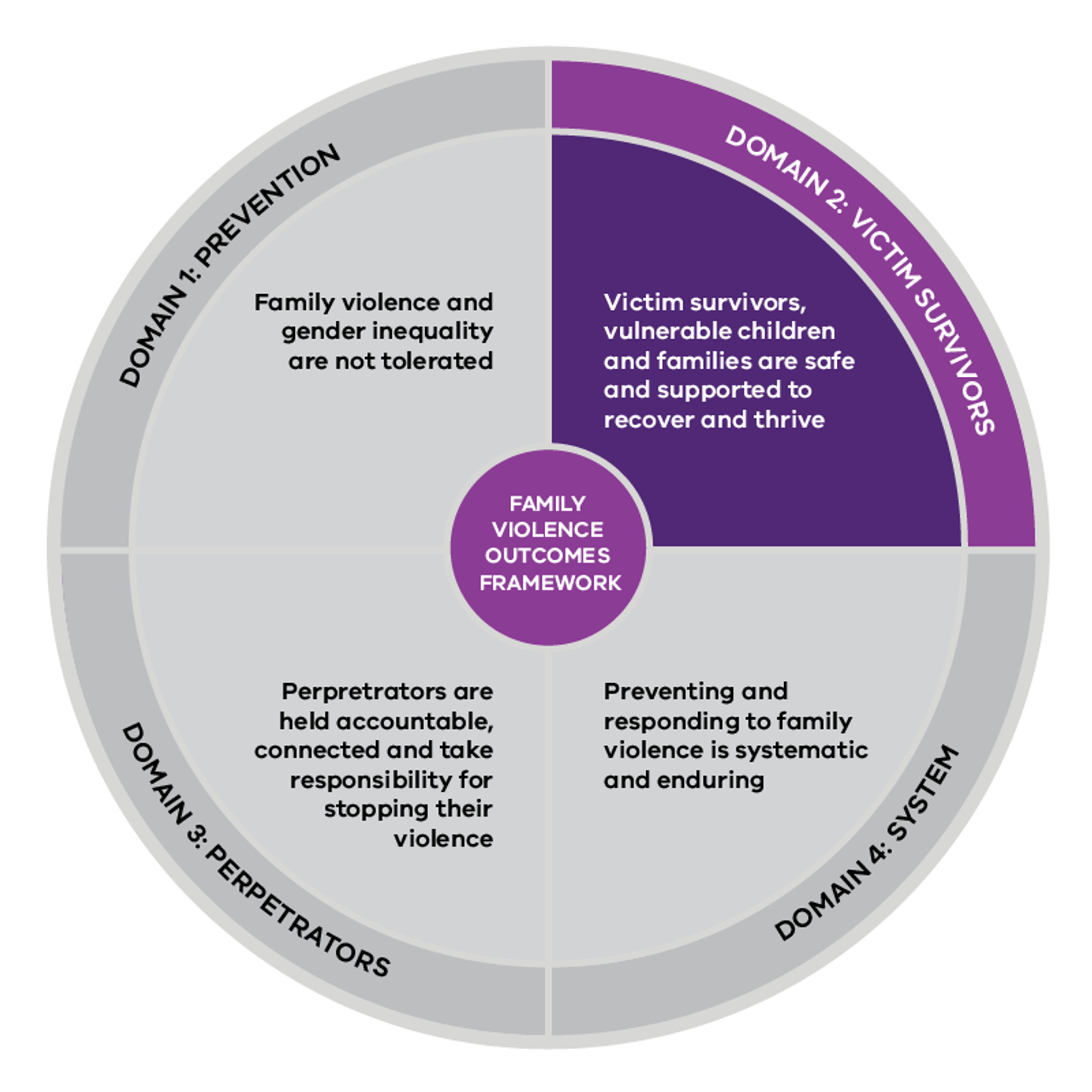

Domain 2: Victim survivors

Victim survivors, vulnerable children and families, are safe and supported to recover and thrive

The Royal Commission found that the service system did not make it easy for victim survivors and families to know what support was available. When they sought help, they encountered a system that was almost impossible to navigate.

Since the Royal Commission, we have worked to ensure victim survivors' voices are central to our efforts to prevent and respond to family violence. The establishment of the Victim Survivors Advisory Council in 2016 enabled victim survivor experiences to frame the development of the reform.

All four domains of the Family Violence Outcomes Framework integrate lived experience as an essential element.

People with lived experience also co-designed The Orange Door, a key service delivery reform to keep victim survivors safe.

The Orange Door provides victim survivors and people affected by family violence with access to services and specialist family violence workers. This includes ‘service navigators’ who assist people through the system to access the support they need. Through these and other changes, victim survivors are beginning to access more timely and responsive assistance, tailored to their own individual circumstances and experiences of family violence.

The data in this domain is sourced primarily via the Crime Statistics Agency. For the 2023 version of the Ending family violence annual report, we expect to include a broader set of measures, including measures where data between different datasets are linked, to provide a broader picture of the reform. We recommend you read this data alongside the breadth of activity in this website’s Rolling Action Plan section.

Outcomes measures data

Families are safe and strong

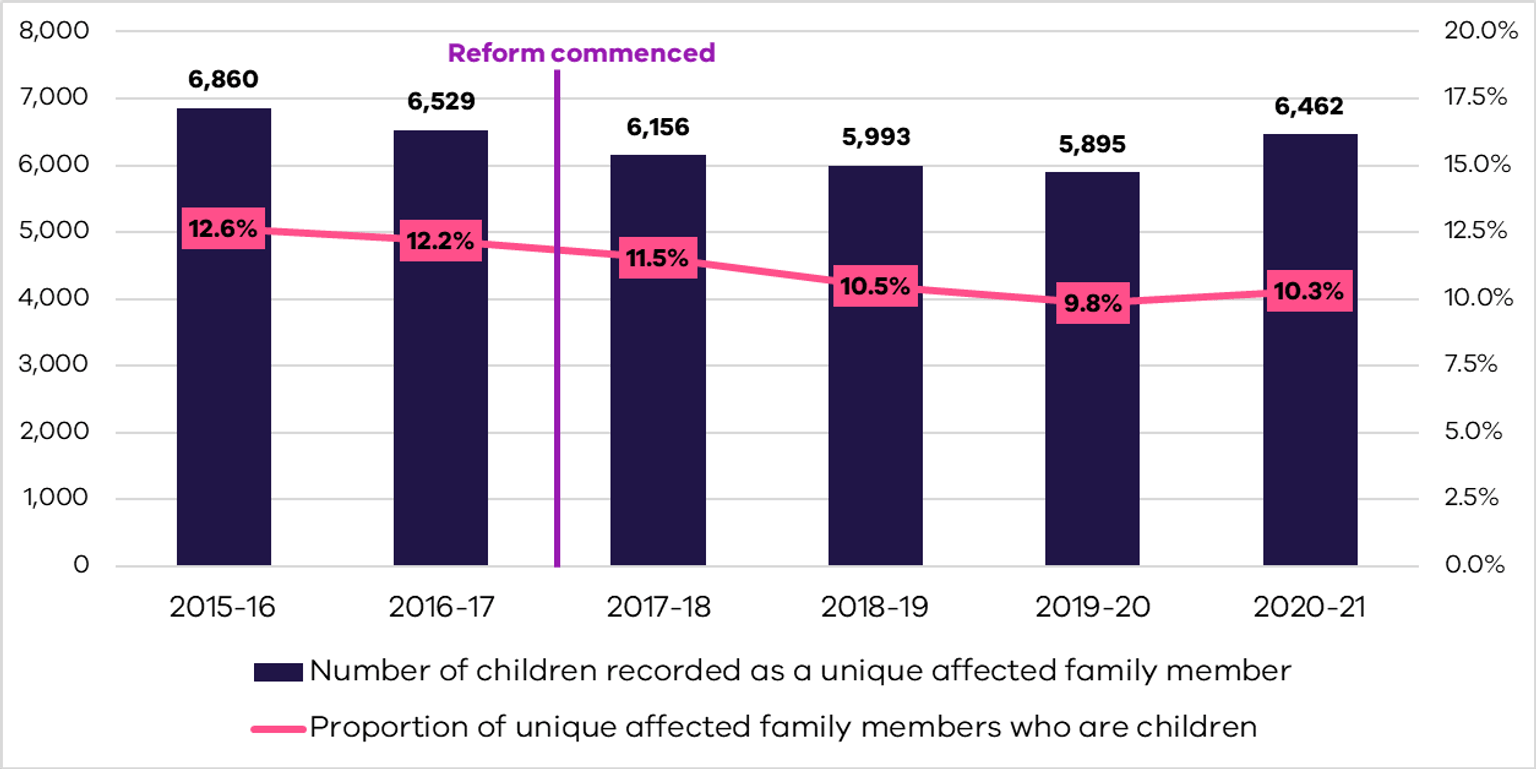

Indicator: Reduction in children and young people who experience or witness family violence

The safety of children is paramount to family violence reform. Children are the most vulnerable members of any family.

Victoria’s family violence reforms recognise children as victim survivors in their own right. Any exposure they may have to family violence, even if it is not directed at them, is considered a family violence incident.

Children who are both directly and indirectly exposed to family violence can be affected by it. It can affect their physical and mental wellbeing, development and schooling. Family violence is the leading cause of children’s homelessness in Australia.1

Measure: Number/proportion of unique affected family members who are children

The number of unique affected family members2 who are children decreased between 2015–16 and 2019–20, before increasing in 2020–21. This reflects the impact of public health restrictions with the closure of social gatherings and outdoor activities. Families were restricted from leaving their homes, and children were not physically attending school. These restrictions may have increased stressors on families.

The increase in children recorded as affected family members during the COVID-19 pandemic may also have been impacted by proactive policing initiatives. These include Operation Ribbon, which monitors the behaviour of high-risk family violence offenders. Operation Ribbon may have contributed to increases in the number of recorded incidents,3 including those involving children.

In 2020–21, children represented 10.3 per cent of unique family members recorded by Victoria Police. This compares with 12.6 per cent in 2015–16. There was a slight yet consistent downward trend in the number and proportion of children affected by family violence until the slight increase in 2020–21. We will continue to monitor these trends.

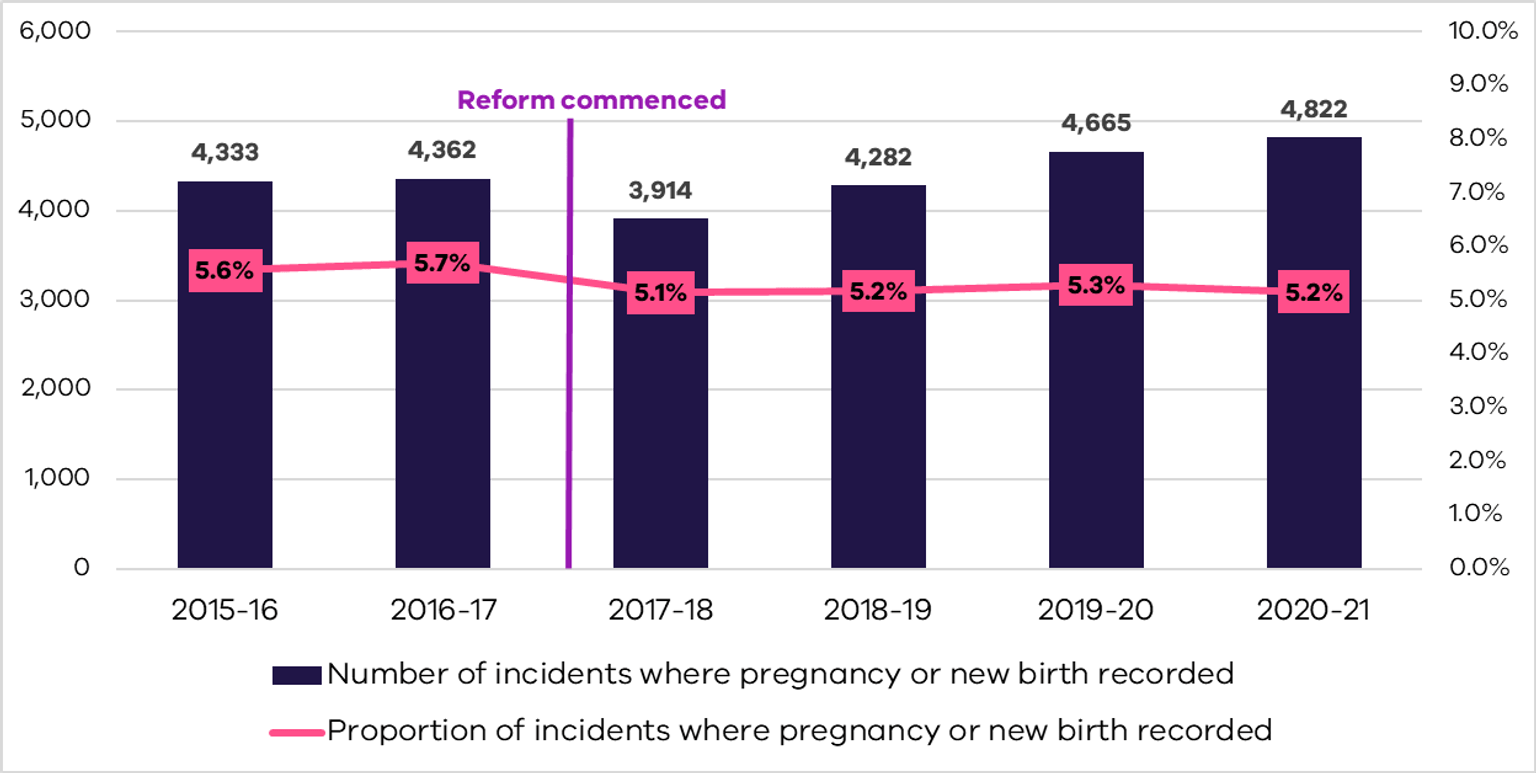

Indicator: Reduction in family violence among women who are pregnant or have a newborn

Family violence during pregnancy is a significant indicator of future harm to the woman and child victim. Family violence often commences or intensifies during pregnancy. It is associated with increased rates of miscarriage, low birth weight, premature birth, foetal injury and foetal death.

Pregnancy and early parenthood are opportune times for early intervention, as women are more likely to have contact with health and other professionals.

Measure: Number/proportion of family violence incidents where ‘pregnancy or new birth’ is recorded

In 2020–21, there were 4,822 family violence incidents where pregnancy or new birth was recorded as a risk factor, reflecting 5.2 per cent of total 2020-21 family violence incidents. This compares to 2015-16 when 4,333 or 5.6 per cent of total family violence incidents recorded pregnancy or new birth

Time series data shows the proportion of incidents where pregnancy or new birth is recorded remained stable over the past six financial-years (between 5.1 per cent and 5.7 per cent).

Victoria Police reported a common factor in some incidents during COVID-19 restrictions was new or expecting parents were under greater pressure and/or stress, particularly those living in smaller residences, with these stress points compounded by other impacts of the restrictions such as working from home, loss of employment and mental health.

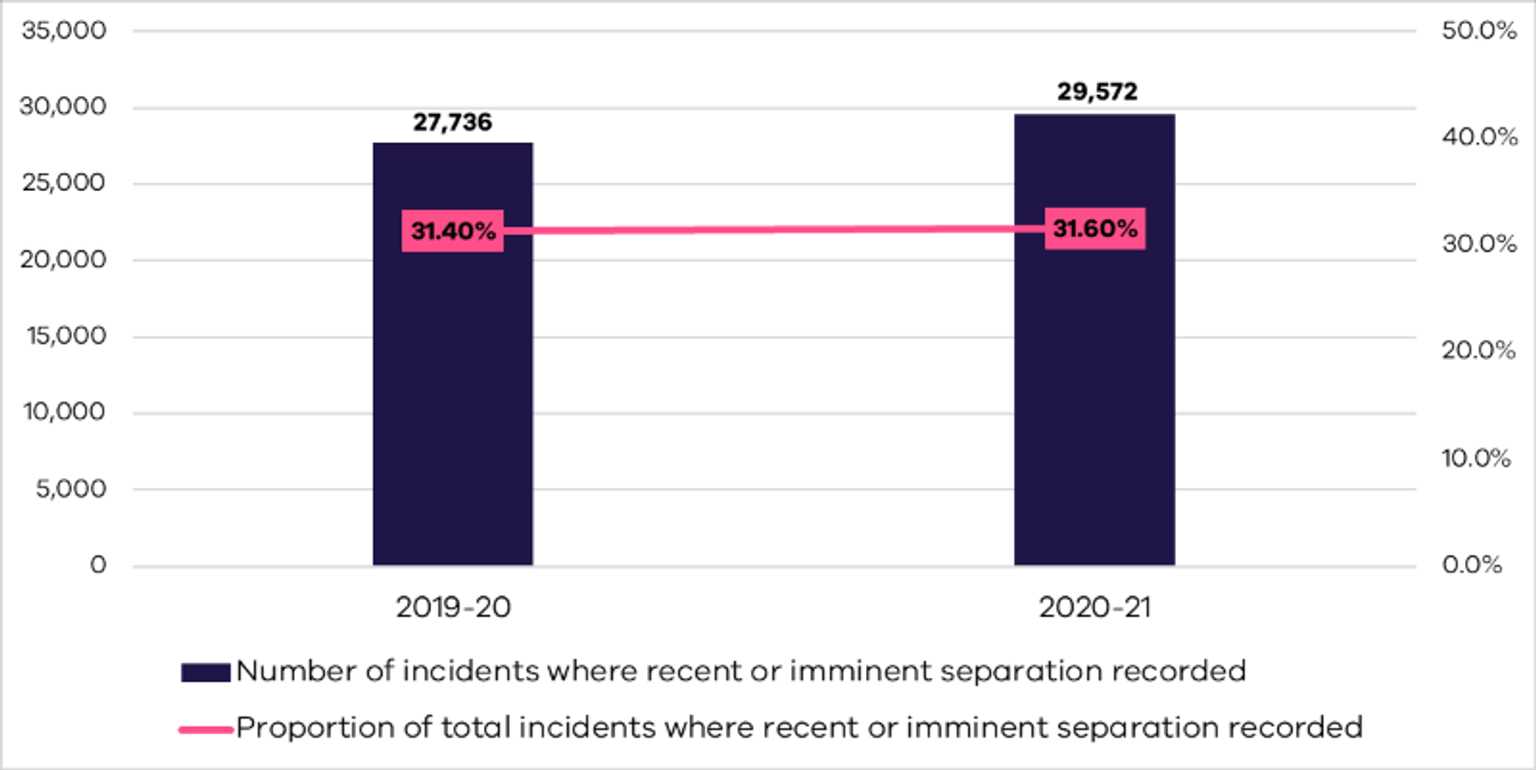

Indicator: Reduction in level of risk for victim survivors immediately post-separation

High-risk periods for people experiencing family violence include when a victim survivor starts planning to leave, immediately prior to taking action, and during the initial stages of, or immediately after, separation.

It is common for perpetrators to continue, and often escalate, their violence after separation. This may be as an attempt to gain or reassert control over a victim survivor, or as punishment for leaving the relationship.

Measure: Number/proportion of family violence incidents where ‘recent or imminent separation’ is recorded

If a family violence incident involves current or former partners, police will record whether the couple recently separated.

In 2020–21, recent separation was recorded in almost one-third (31.6 per cent) of family violence incident reports. The proportion of incidents where recent or imminent separation was recorded has remained stable since 2019–20 (31.4 per cent).

In 2019–20, Victoria Police introduced statewide changes to family violence recording practices through a new Risk Assessment and Risk Management report (L17). The new assessment report was accompanied by training, resulting in an overall uplift in frontline police knowledge. It is structured with conversational rather than tick-box questions.

These changes to recording practices mean that it is not practical to compare data prior to 2019. This is because there is no way to accurately measure population-level change over time.

Notes

1 Campo M 2015, Children’s exposure to domestic and family violence: Key issues and responses, CFCA paper no. 36, Australian Institute of Family Studies, p. 5, https://aifs.gov.au/cfca/publications/childrens-exposure-domestic-and-f…

2 A unique affected family member is defined as a person who has had one or more family violence incidents recorded in the LEAP database within the relevant reference period. A unique affected family member may be recorded in more than one incident during the reference period. However, they will have a count of 1 in the data presented concerning unique affected family members.

3 Rmandic S, Walker S, Bright S and Millsteed M 2020, ‘Police-recorded crime trends in Victoria during the COVID-19 pandemic’, in brief, no. 10, September 2020, Crime Statistics Agency, https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2020-09/apo-nid30…

Victim survivors are safe

Indicator: Decrease family violence deaths

Measure: Number of family violence-related deaths

Family violence, in particular intimate partner violence, contributes to more death, disability and illness in adult women than any other preventable risk factor.1

The Coroners Court of Victoria identifies how many homicides each year are related to family violence.

It is difficult to assess changes in the number of family violence homicides over time, in part due to the small number of incidents. There may be large fluctuations over time that are not significant.

The lag between when a homicide is reported to the register and when an investigation concludes (and thus identifies whether a homicide was related to family violence) further limits our ability to assess change. For 2019–20 and 2020–21 data, the higher number of ‘unknowns’ reflects this lag.

Noting the above limitations, data from 2020–21 does not indicate that the number of family violence homicides is decreasing. In 2020–21, 25 homicides related to family violence were reported to the VHR, with a further 19 yet to be determined whether they are related to family violence.

This number of family violence homicides is the highest reported since 2015–16.

Number of family violence-related homicides by financial year – 2015-16 to 2020-21

| Number of homicide deceased | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family violence related | 33 | 24 | 21 | 15 | 21 | 25 |

| Not family violence related | 38 | 31 | 37 | 31 | 37 | 19 |

| Other | ≤ 3 | 7 | 4 | 9 | 23 | 19 |

Source: Coroners Court of Victoria data extracted from the Victorian Homicide Register (VHR) by the Crime Statistics Agency

Notes

1Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2018, Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia, 2018, <https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/domestic-violence/family-domestic-sexua…;.

Victim survivors rebuild lives and thrive

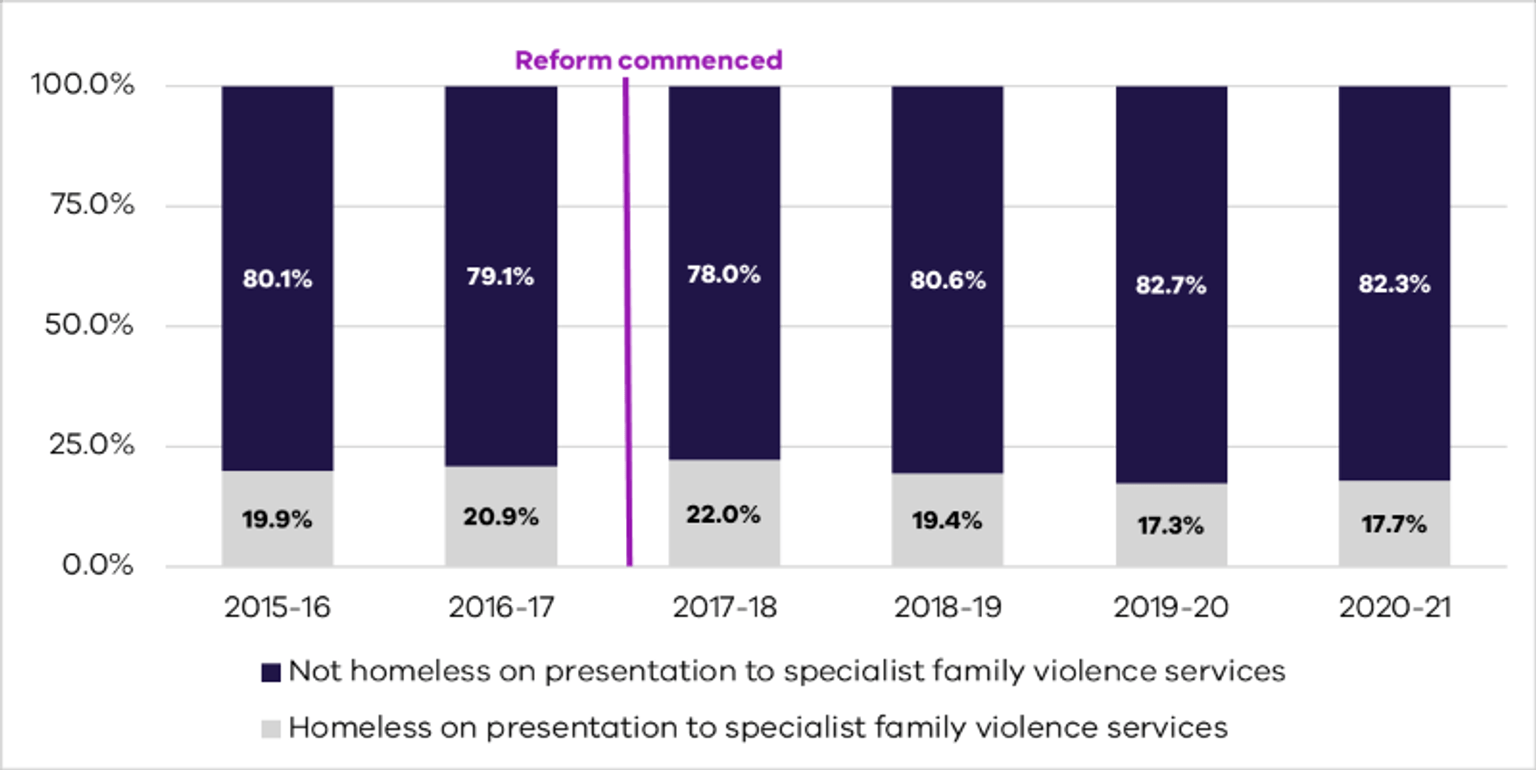

Indicator: Increase in victim survivors who have safe, secure, stable and affordable housing

Family violence is recognised as a leading cause of homelessness, especially for women and children.

Homelessness can occur as a direct result of experiencing family violence – for example, having to leave the home for safety from a perpetrator’s use of violence. Structural barriers including gender inequality, a lack of affordable housing, and limited social support can also prevent victim-survivors from finding a safe and secure place to live.

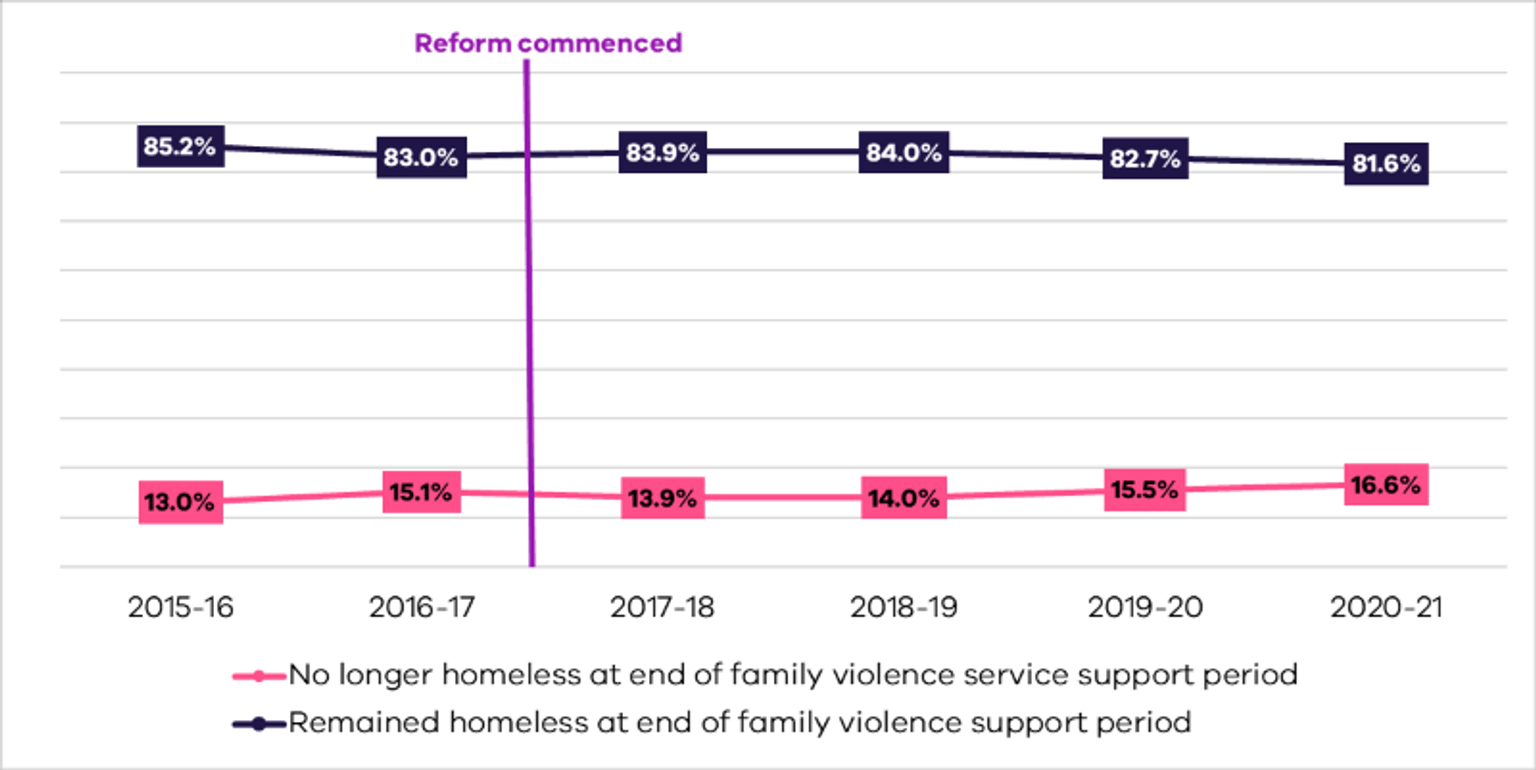

Measure: Proportion of victim survivors who are homeless or without a permanent place to live

In 2020-21 there were 5,472 family violence service cases1 where victim survivors identified themselves as homeless. This was an increase from 4,693 in 2015–16.

Despite the increase in numbers, the proportion of family violence cases where victim survivors identified as homeless decreased slightly from 19.9 per cent in 2015–16 to 17.7 per cent in 2020–21.

Data shows that clients accessing refuges make up the greatest proportion of victim survivors experiencing homelessness. This cohort also tends to be at highest risk as they are often forced to leave their homes to escape the violence.

Family violence is the number one cause of homelessness for women. Stable housing is identified as a critical protective factor in promoting safety, wellbeing and recovery for victim survivors of family violence.

Measure: Number and Proportion of victim survivors who experience an improvement in their housing situation after receiving a service

There has been an increase in the number and proportion of victim survivors receiving family violence support who indicated they were homeless at the start of their support period and were in secure housing by the end of their support period.

In 2020–21, there were 877 family violence service cases where victim survivors who identified as homeless on presentation were recorded in secure housing at the end of their support period. This represents 16.6 per cent of total family violence service cases and compares with 590, or 13.0 per cent, in 2015–16.

Despite the above improvement, in 2020–21 about 80 per cent of family violence service cases with victim survivors who indicated homelessness when they initially accessed family violence support services remained homeless when their support period ended.

Many family violence refuge clients exit the system to transitional housing and other temporary accommodation arrangements (which fall within the definition of homelessness) while they await a more stable and secure housing pathway.

Notes

1In this report, ‘family violence cases’ count one client per presenting group or household.

Domain 3: Perpetrators

Perpetrators are held accountable, connected and take responsibility for stopping their violence

Perpetrator accountability is everybody’s business.

The Royal Commission into Family Violence recommended a response that links all parts of the service system, including government, justice and social services sectors.

This needs to be done to overcome the existing fragmented and episodic response to perpetrators. It will also create a mutually reinforcing ‘web of accountability’ that:

- stops perpetrators from committing further violence

- keeps them in view

- holds them to account

- supports them to change their behaviour and attitudes.

The system can and should hold perpetrators responsible for their behaviour. However, only perpetrators themselves can choose to end their use of violence.

Every time a perpetrator interacts with the service system, there is an opportunity to effect behaviour change. If interventions are targeted to the right perpetrators at the right time, it can avoid significant costs to victim survivors, the community and government.

The outcomes and indicators in this domain were refreshed through a consultation process in 2020. The refresh focused on broadening the scope of the domain to ensure it reflects whole-of-system accountability, in line with recommendations by the Expert Advisory Committee on Perpetrator Interventions.

We are focused on strengthening this domain, with refreshed measures presently in development. We have also commenced work to develop and implement client outcomes measurement for perpetrators participating in interventions, including perpetrator accommodation support services and behaviour change programs. This work is supported by the development of a whole-of-Victorian Government theory of change and monitoring and evaluation framework for perpetrator interventions.

Outcomes measures data

Perpetrators stop all forms of family violence behaviour

Indicator: Reduction in all family violence behaviours

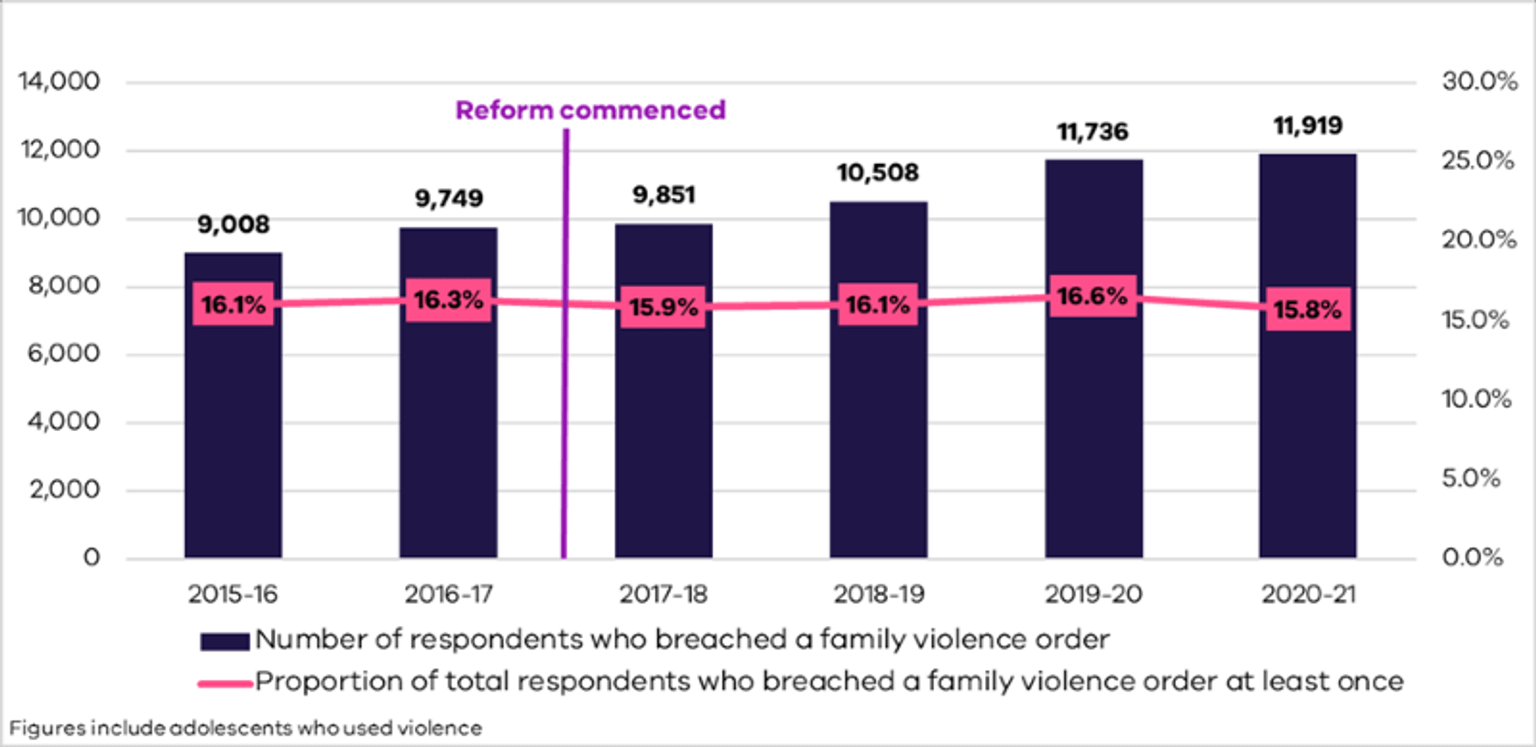

Measure: Number/proportion of reported contraventions of Family Violence orders

Family violence orders are a key mechanism to help keep victim survivors, including children, safe and hold perpetrators accountable. Perpetrators who breach an order can be charged with a criminal offence.

Most people on a family violence order1, 2 are not recorded by police for a breach of order offence. In 2020–21, 63,711, or 84.2 per cent of people on an active order were not recorded with a breach.

Although most people do not breach, in 2020-21, 11,919 people were recorded with at least one breach of a family violence order. This was an increase from 9,008 in 2015–16.

Despite the increase in numbers, the proportion of people who breach a family violence order has remained consistent (between 15.8–16.6 per cent) during this time.

Proportion of people on a family violence protection order who breach the order - by number of breaches - 2015-16 to 2020-21

| Family violence protection orders and breaches | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of people on active family violence protection order breaches | 56,047 | 59,772 | 62,045 | 65,460 | 70,799 | 75,630 |

| 0 (did not breach) | 83.9% | 83.7% | 84.1% | 83.9% | 83.4% | 84.2% |

| 1 breach | 7.6% | 7.3% | 7.0% | 7.0% | 7.3% | 6.6% |

| 2 breaches | 2.9% | 2.9% | 3.0% | 3.0% | 3.0% | 2.8% |

| 3 breaches | 1.5% | 1.5% | 1.3% | 1.3% | 1.4% | 1.3% |

| 4 breaches | 0.9% | 1.1% | 1.0% | 1.1% | 1.0% | 1.0% |

| 5 or more breaches | 3.2% | 3.5% | 3.6% | 3.7% | 3.8% | 4.1% |

| Proportion of people who breached (combined) | 16.1% | 16.3% | 15.9% | 16.1% | 16.6% | 15.8% |

Source: Victoria Police LEAP data collected by Crime Statistics Agency

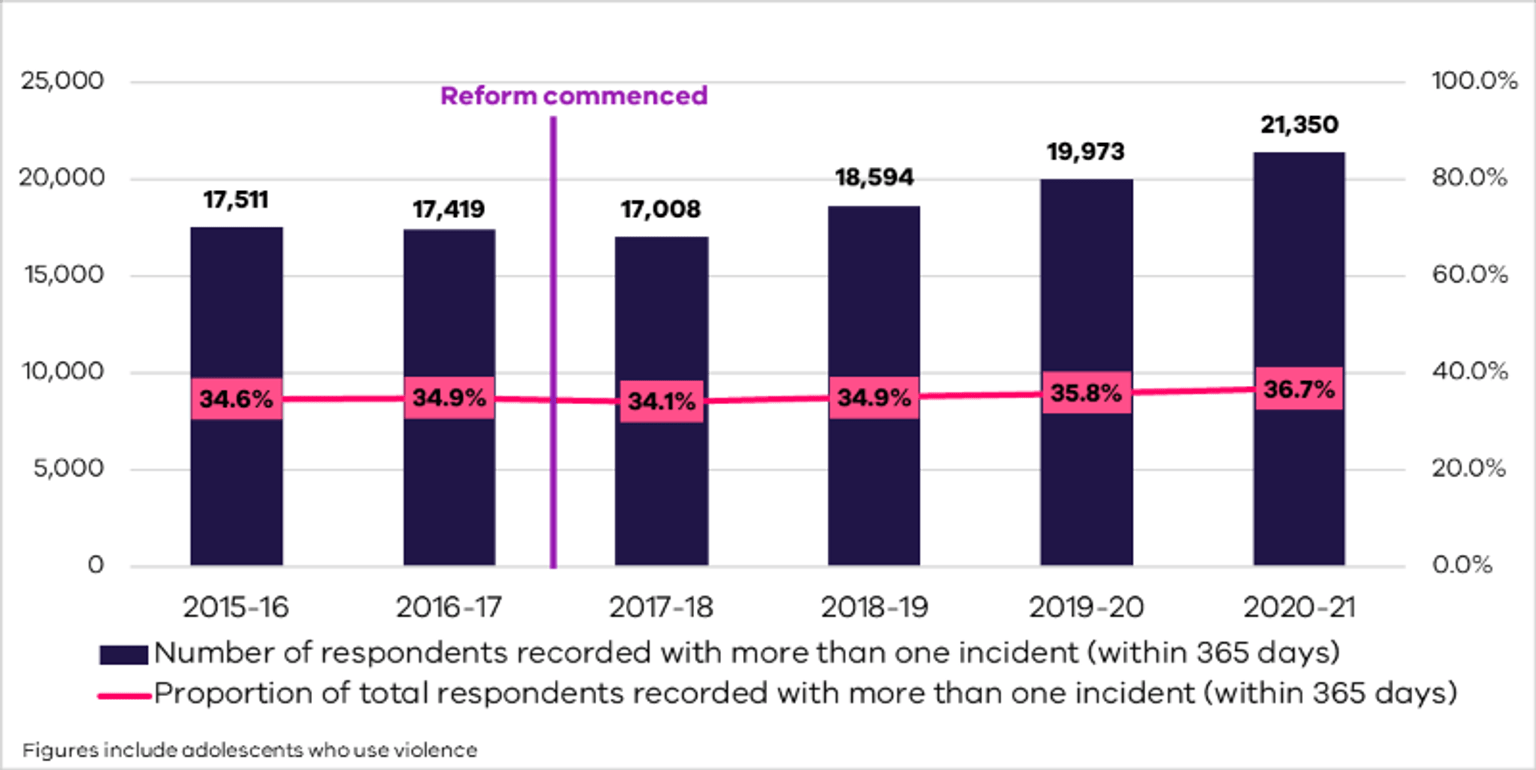

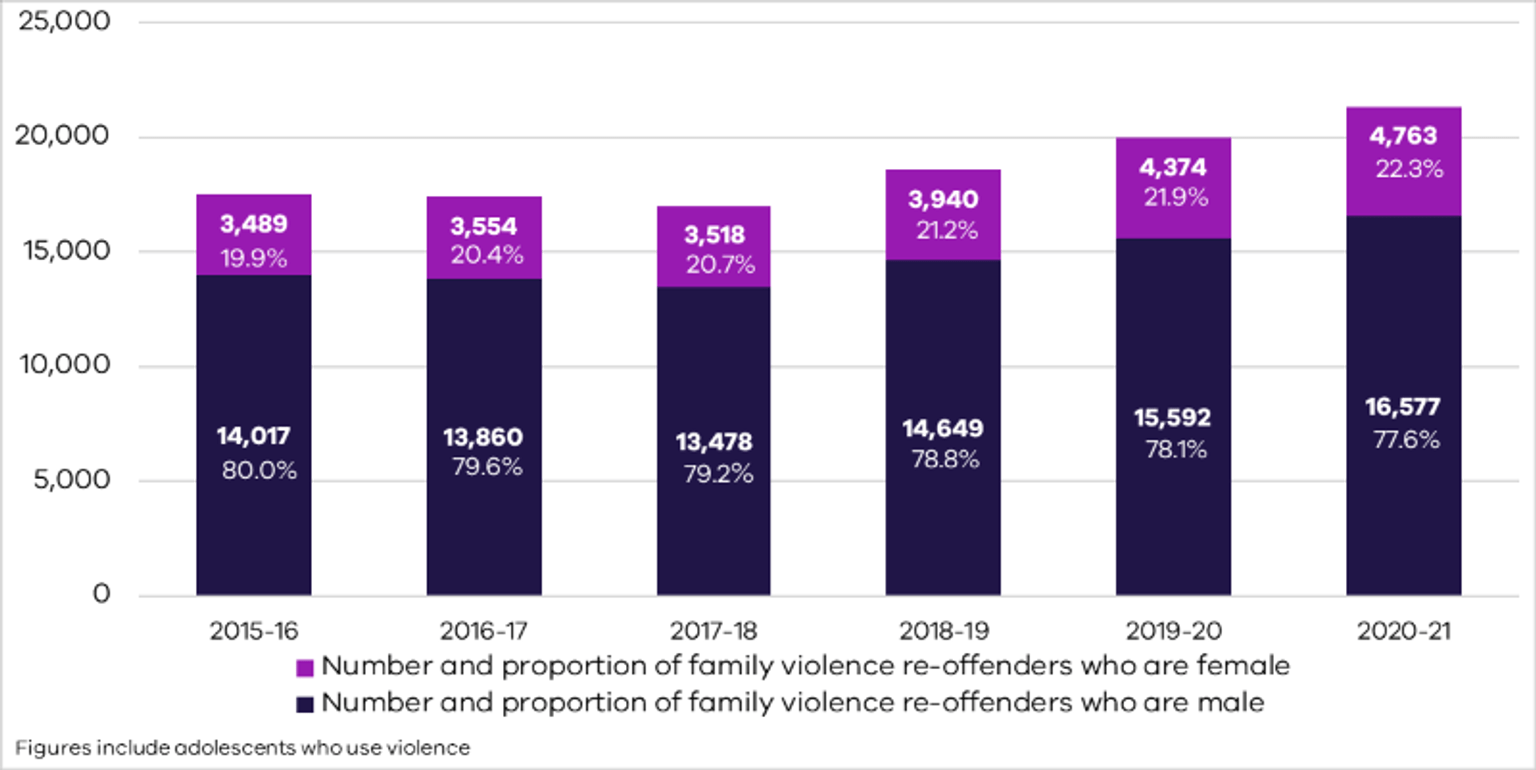

Measure: Number/proportion of individuals identified as the respondent in an L17 report who receive a subsequent L17 report within 12 months

In 2020–21, just over one-third of respondents (36.7 per cent) were associated with more than one family violence incident over a 365-day period.

The proportion of unique respondents with more than one family violence incident has not changed substantially over time.

During the six-year period, male respondents were more likely to be recorded with subsequent incidents.

Notes

1The figures in this measure refer to people on orders including a family violence intervention order, interim family violence intervention order and/or a family violence safety notice.

2A person can be on more than one active order within the reference period.

Domain 4: System

Preventing and responding to family violence is systemic and enduring

The Royal Commission found the family violence system was complex and difficult to navigate across the many services and systems. This included the justice system, legal services, police, specialist family violence services, housing, child protection and health services.

A whole of government approach is required to transform how we prevent and respond to family violence. This involves fundamental changes to ensure all service systems are able to:

- identify, assess, manage and respond to victim survivors and perpetrators

- deliver better outcomes for those affected by family violence.

Outcomes measures data

The family violence system is integrated

Indicator: Increased sharing of information to assess and respond to needs and risks

Having a shared understanding supports successful system integration. This includes having workforces who understand their responsibilities to identify and respond to family violence. It also means having an accessible, equitable and effective system response.

The Central Information Point is one way we are increasing collaboration between services through information sharing.

The Central Information Point is a targeted, cross-government information sharing service. It aims to improve access to risk-relevant information to support victim survivors.

It also helps to keep those who use violence in view and more accountable for their actions. The Central Information Point consolidates critical information about a perpetrator into a single report. This assists with family violence risk assessment and management.

Central Information Point reports enable family violence frontline workers, such as at The Orange Door and Risk Assessment and Management Panels, to access information about a perpetrator. Sources include Court Services Victoria, Victoria Police, Corrections Victoria and the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing (Child Protection).

Information provided through the Central Information Point also allows victim survivors to be more empowered to make decisions about their safety and increases accountability of perpetrators for their decisions and actions.

Measure: Number of Central Information Point reports provided to services

The Central Information Point continues to respond to demand from The Orange Door in existing areas and as the network expands across Victoria. The number of Central Information Point reports delivered annually has increased from 2,902 in 2018–9 to 4,027 in 2020–21 (a 39 per cent increase).

The difference between the number of requests received and the reports delivered is due to a number of administrative processes.

These include the request being cancelled or withdrawn. This may occur if a Central Information Point report has recently been delivered for the same perpetrator, and the practitioner already has access to that information.

A request may also be withdrawn or cancelled if it is incomplete or inaccurate and a new request is submitted.

The family violence and broader workforce across the system are skilled, capable and reflect the communities they serve

Indicator: Increase workforce diversity

Measure: Number/proportion of workforce who identify as from a priority community – ATSI, CALD, LGBTIQ+, disability

The Royal Commission highlighted the lack of detailed knowledge and essential workforce data about family violence workers in Victoria.

To address this gap, we undertake the family violence workforce census every two years. The census collects data and information about family violence workforces.

The following indicators and measures use the survey results from the 2019–20 census. Subsequent results will be compared with these to identify any progress made.

In 2019–20, most family violence workers identified as female (85–87 per cent), with 1 per cent identifying as non-binary (self-described).

Between 7 per cent and 13 per cent of the specialist family violence response and primary prevention workforces are classified as having a disability. This means they experience difficulties or restrictions which affect their participation in work activities.

Between 3–4 per cent of workers identified as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander.

Between 6–7 per cent of workers spoke languages other than English at home.

Family violence workforce diversity 2019–20: specialist family violence response workforce

| Priority community | Number of responses | Total responses to questions | Proportion of workforce responses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander | 41 | 1,357 | 3% |

| Person with a disability (This refers to people who experience difficulties or restrictions which affect their participation in work activities) | 94 | 1,366 | 7% |

| Speaks a language other than English at home | 97 | 1,384 | 7% |

| Uses their culture or faith-based knowledge and experience in undertaking their work | 478 | 1,196 | 40% |

| Born outside of Australia | 273 | 1,363 | 20% |

| Self-described gender | 14 | 1,374 | 1% |

| Age 55-74 | 278 | 1,391 | 20% |

Source: Family Violence Workforce Census 2019–20

Family violence workforce diversity 2019–20: primary prevention workforce

| Priority community | Number of responses | Total responses to questions | Proportion of responses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander | 17 | 435 | 4% |

| Person with a disability (This refers to people who experience difficulties or restrictions which affect their participation in work activities) | 56 | 429 | 13% |

| Speaks a language other than English at home | 26 | 437 | 6% |

| Uses their culture or faith-based knowledge and experience in undertaking their work | 135 | 387 | 35% |

| Born outside of Australia | 86 | 431 | 20% |

| Self-described gender | 4 | 438 | 1% |

| Age 55-74 | 107 | 445 | 24% |

Source: Family Violence Workforce Census 2019–20

Indicator: Increase workforce skills and capabilities

Measure: Number/proportion of workforce who report confidence they have enough training and experience to perform their role effectively

Many workforces that intersect with family violence – including in mainstream and universal services – require training to build the family violence prevention and response capability across the system.

We have heard through our engagement with family violence practitioners that there is a strong association between receiving training in family violence or primary prevention and feeling confident to identify and respond to those experiencing family violence.1

Accordingly, this training is fundamental to the success of the family violence reforms, particularly The Orange Door, the Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme and the Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management (MARAM) framework.

In the 2019–20 Family Violence Workforce Census, at least half of the family violence workforce (61 per cent for specialist family violence response and 50 per cent for primary prevention) felt very to extremely confident in their level of training and experience to complete their role.

The survey identified that confidence rose with age and years of experience.

The top-two identified areas for additional support required to increase confidence for both cohorts were:

- further information sharing and collaboration with other service providers

- a community of practice for each cohort.

Family violence workforce confidence in level of training and experience 2019–20: specialist family violence response workforce (total responses 1,486)

| Confidence rating | Number of responses | Proportion of responses |

|---|---|---|

| Extremely confident | 178 | 12% |

| Very confident | 728 | 49% |

| Moderately confident | 446 | 30% |

| Slightly confident | 104 | 7% |

| Not confident | 15 | 1% |

Source: Family Violence Workforce Census, 2019–20

Family violence workforce confidence in level of training and experience 2019–20: primary prevention workforce (total responses 463)

| Confidence rating | Number of responses | Proportion of responses |

|---|---|---|

| Extremely confident | 60 | 13% |

| Very confident | 171 | 37% |

| Moderately confident | 171 | 37% |

| Slightly confident | 46 | 10% |

| Not confident | 19 | 4% |

Source: Family Violence Workforce Census, 2019–20

Indicator: Increase in health, safety and wellbeing of the family violence workforce

Measure: Number/proportion of workforce who report work-related stress

Work-related stress can lead to burnout (prolonged physical and psychological exhaustion).

This affects workers in ways including:

- physical and emotional stress

- low job satisfaction

- feeling frustrated by or judgemental of clients

- feeling under pressure, powerless and overwhelmed

- frequent sick or mental health days

- irritability and anger.

Family violence workforce work-related stress 2019–20: specialist family violence response workforce

| Work-related stress level | Number of workers | Proportion of workforce responses |

|---|---|---|

| None | 14 | 1% |

| Low | 303 | 21% |

| Moderate | 649 | 45% |

| High | 332 | 23% |

| Very high | 116 | 8% |

| Severe | 29 | 2% |

| Total | 1,443 | 100% |

| Feels safe performing role | Number of workers | Proportion of workforce responses |

|---|---|---|

| Always or often | 1,213 | 85% |

| Sometimes or less often | 214 | 15% |

| Total | 1,427 | 100% |

Source: Family Violence Workforce Census, 2019-20

Family violence workforce work-related stress 2019–20: primary prevention workforce

| Work-related stress level | Number of workers | Proportion of workforce responses |

|---|---|---|

| None | 5 | 1% |

| Low | 105 | 23% |

| Moderate | 206 | 45% |

| High | 92 | 20% |

| Very high | 41 | 9% |

| Severe | 9 | 2% |

| Total | 458 | 100% |

| Feels safe performing role | Number of workers | Proportion of workforce responses |

|---|---|---|

| Always or often | 397 | 88% |

| Sometimes or less often | 54 | 12% |

| Total | 451 | 100% |

Source: Family Violence Workforce Census, 2019-20

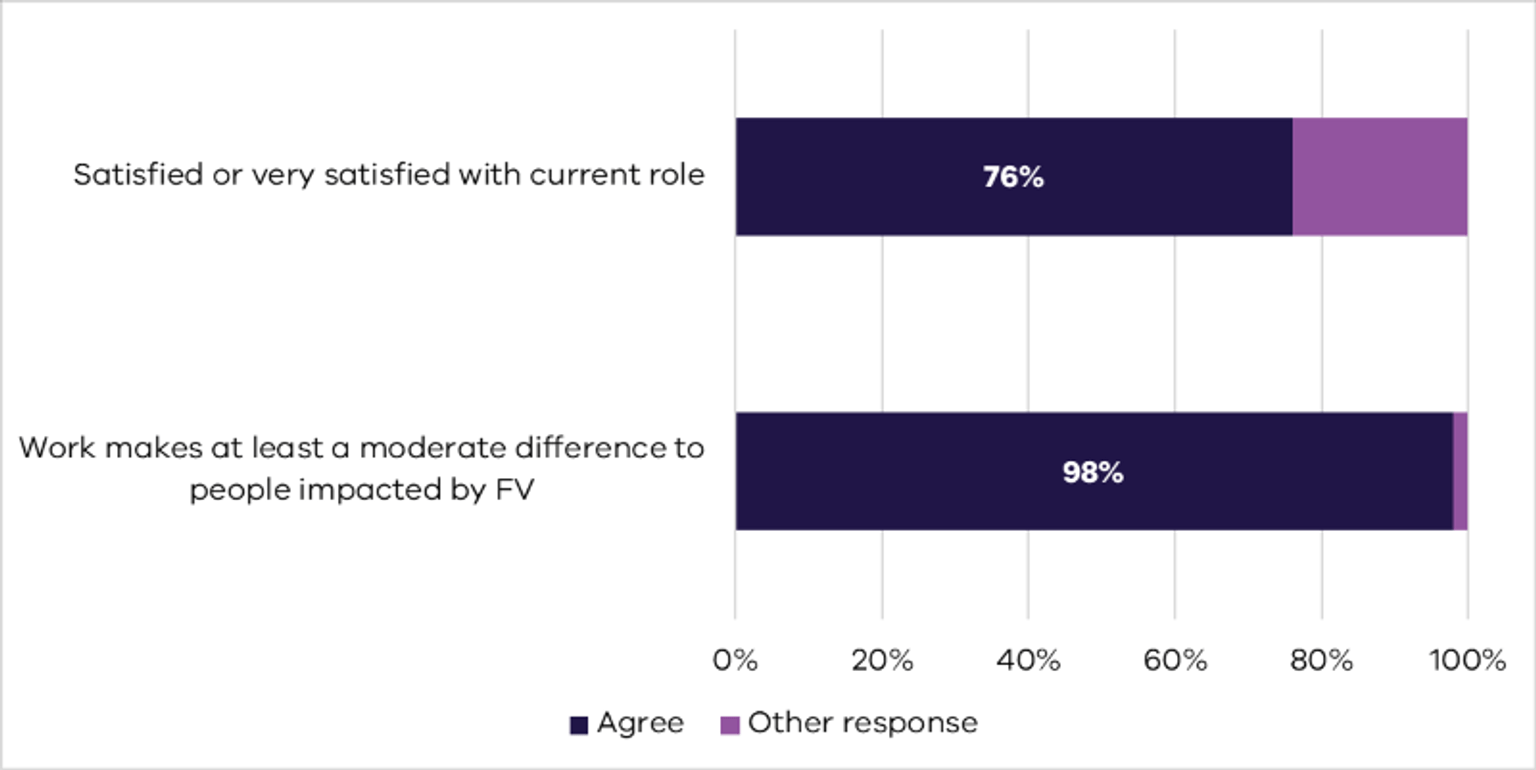

Most workers in both the specialist family violence response and primary prevention workforces experience at least moderate stress, with approximately one-third experiencing at least high levels of stress.

High workload is the key driver of high, very high and severe levels of stress in these workforces. Half the cohort reports that they only sometimes have sufficient time to complete tasks.

Positively, over 75 per cent are satisfied to very satisfied with their current role. Nearly all workers felt their work made a moderate to significant difference to people affected by family violence.

Notes

1Family Safety Victoria 2019, Building from strength: 10-year industry plan for family violence prevention and response, State Government of Victoria, Melbourne.

Rolling Action Plan 2020–2023 activities

Working towards a Victoria free from family violence

The Rolling Action Plan 2020-2023, is a coordinated cross-government plan to implement the next stage of the 10-year plan. It was launched as Victoria continues to respond to the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

It carries on from the first Rolling Action Plan 2017-2020. This laid a solid foundation for investment and activities.

The second Rolling Action Plan builds on this. It includes new areas of focus.

Its goal is that by 2023, we will have a system that is:

- more connected, sustainable and focused on preventing violence before it starts

- delivering better outcomes for victim survivors

- holding perpetrators to account.

This report focuses on activities that have been committed to in the Rolling Action Plan. It reflects considerable work over the past year across government and statutory authorities. These include:

- Court Services Victoria

- Department of Education and Training

- Department of Families, Fairness and Housing

- Department of Health

- Department of Justice and Community Safety

- Respect Victoria

- Victoria Police.

This is not a comprehensive report on all work under way to reform the way we prevent and respond to family violence.

The sector constantly adapts to needs, risks and situations as they arise, beyond the actions in the Rolling Action Plan. This reflects our commitment to embedding lasting, sustainable change across the system.

This report focuses on the achievements across the whole of the sector. It only refers to departments or authorities where required.

You can see what has been delivered against each of the priority areas by selecting the relevant area in the side menu.

Each section sets out:

- what we have achieved

- what we are focused on delivering

- how these activities will contribute to the family violence reform outcomes.

Activities might be mentioned across a number of different priority areas. This reflects the fact they contribute to the delivery of multiple priorities. Where possible, this has been minimised to reduce duplication.

Activities are reflected in the primary priority area they contribute to. For example, the Prevention of Family Violence Data Platform contributes to both the Primary prevention priority area and the Research and evaluation priority area.

Rolling Action Plan 2020–2023 activity status

Of the 212 activities that we committed to in the Rolling Action Plan:

- 40 have been completed

- another 146 are in progress, 37 of which are expected to be completed in the first half of 2022

- 16 activities have been delayed

- a further 10 activities are scheduled to commence in 2022 or 2023.

The COVID-19 pandemic interrupted the delivery of some activities under the Rolling Action Plan and required some reprioritisation.

Necessary public health measures contributed to an increased risk of family violence and affected the ability of services to respond to those experiencing family violence.

Victorian Government resources were in some cases redeployed to support the COVID-19 response. This affected the implementation of the Rolling Action Plan, as did disruptions to building activities such as for new housing and court facilities.

However, despite the many challenges associated with the pandemic, significant progress has been made in delivering actions under the Rolling Action Plan. This reflects the agility and responsiveness of the family violence sector during this period.

Download:

Overarching priorities

Examining the reform through the lens of intersectionality, Aboriginal self-determination, lived experience, sexual violence and harm and children and young people

There are several themes that cut across our family violence reform work. The Rolling Action Plan 2020–2023 addresses the following three priorities:

- Intersectionality recognises people are diverse and that characteristics such as race, age, class, ability, sexuality and gender can combine to create overlapping systems of discrimination and disadvantage.

- Involving people with lived experience of family violence in the design, delivery and evaluation of our work to prevent and respond to family violence helps ensure it is inclusive and accessible and leads to better outcomes for all Victorians.

- Aboriginal self-determination creates policies and structures that put Aboriginal communities at the heart of decision making on the matters that affect their lives. For further information, refer to the Dhelk Dja priority area.

Additional themes that cut across family violence reform have emerged during the development of the Rolling Action Plan:

- Adults, children and young people often experience sexual violence, abuse and harm (also referred to as sexual assault) in a family violence context. Reforms to the family violence system must take this into account.

- Children and young people are victim survivors of family violence in their own right. They have distinct needs.

There are limited Rolling Action Plan activities specifically related to sexual violence abuse and harm, and children and young people. However, these themes are considered across the delivery of all areas of family violence reform.

We also know that effective reform oversight and governance is critical to delivering family violence reform. Our governance and oversight structures continue to evolve in response to the maturity and progress of the reform.

This section reports directly on some activities contributing to overarching themes. However, activities reported in other priority areas also have reform-wide impacts, such as:

- the Workforce development priority area, which includes building the capacity and capability of specialist family violence services. This includes, for example, responding to the experience of diverse groups such as people from the LGBTIQ+ community, people with a disability, children and young people, and people from refugee and migrant backgrounds

- the Research and evaluation priority area, which includes developing consultation guidelines on incorporating lived experience into family violence program evaluations.

What has happened

What is next

Intersectionality

- Capability building and strengthening of the workforce will continue through the LGBTIQ+ Family Violence Capacity Building initiative. It will also involve recruitment and engagement with family violence and disability practice leaders.

- We will continue to develop a Victorian elder abuse statement. This will set out our commitment to ending elder abuse in family violence contexts. It will outline the partnerships required to support older people experiencing family violence. It will also set expectations for the family violence service system to support older people.

- Over the next two years, we will strengthen engagement with multicultural and faith communities on the family violence reforms. This will build opportunities to strengthen engagement and build the capability of workforces of multicultural organisations. It will increase their knowledge and skills to support clients experiencing or at risk of family violence. We will also support cross-sectoral collaboration between multicultural, ethno-specific and faith-based organisations, specialist family violence services and The Orange Door network.

- The case management program requirements will be consolidated into a single document. This will include roles and responsibilities in the provision of emergency accommodation and after-hours services. This will integrate case management program requirements into all stages of support.

Reform oversight and governance

The Family Violence Reform Advisory Group will continue to meet three times a year. It will advise government on system-level impacts of family violence reforms. It will also consider opportunities for improvement in service provision.

Sexual violence and harm

- The Family Violence Graduate program provides a pathway for new and recent graduates into the family violence, primary prevention and sexual assault sectors. The program ran in 2021 and will continue in 2022.

- The Whole of Victorian Government sexual violence and harm strategy will be launched.

Children and young people

Victoria will continue to work closely with the Commonwealth, states and jurisdictions to influence a strong National plan on the safety of women and children and its supporting five-year action plan.

What this means for outcomes

Courts priority area

Reforming the courts response to family violence

The court is often a crucial part of a victim survivor’s journey when seeking protection from family violence. The court system is being transformed to make it safer for victim survivors and families. This will ensure people have the support they need, including supporting respondents to change their behaviour.

We are also working to make courts accessible, so our diverse Victorian community has equal access to justice.

Specialist Family Violence Courts are the centrepiece of family violence reforms to the courts system.

These courts provide a trauma-informed response to family violence. They give victim survivors more choice over their court experience. They also provide greater access to support services that help victim survivors at court and beyond.

The work occurring through the Rolling Action Plan focuses on:

- strengthening court reforms

- improving services to keep victim survivors and families safe through the court system

- holding perpetrators of family violence to account.

This work also continues to develop and refine technology-driven initiatives, building on recent experience from the COVID-19 pandemic.

What has happened

What is next

Most activities within this priority area will continue through until 2023. The timeframes for delivery acknowledge the complexity of creating change within our court system. They provide sufficient time to achieve this in a way that will ensure sustained outcomes for Victoria.

Continuing activities include:

- planning for the gazettal of a further seven Specialist Family Violence Courts in 2022, as well as planning for the associated capital works to be delivered over the coming years through to 2025

- expanding the availability of Court Mandated Counselling Orders to other headquarter court locations

- progressing the development and implementation of the Magistrates’ Court of Victoria Koori family violence strategy. This will guide how the court approaches family violence in the Aboriginal community

- expansion of online and remote capabilities, including expansion of supported remote hearing access to a further 10 non-court locations

- enhancements to the online family violence intervention order application process. These changes will help reduce the need for a victim survivor to physically attend a court building

- training and capability building will continue across the workforce including:

- family violence training to judiciary and court staff

- MARAM-focused training to judiciary and court staff, including to support those who work with respondents

- training of specialist staff and multidisciplinary training of judiciary and court staff in the Specialist Family Violence Courts.

What this means for outcomes

Dhelk Dja: Safe Our Way priority area

Strong Culture, Strong Peoples, Strong Families

We recognise that family violence is not a part of Aboriginal culture. We also recognise that family violence against Aboriginal people is perpetrated by both non-Aboriginal and Aboriginal people. We acknowledge that colonisation, dispossession, child removal and other discriminatory governmental policies have resulted in significant intergenerational trauma, structural disadvantage and racism. These have had long-lasting and far-reaching consequences.

Victoria has committed to an Aboriginal-led agreement Dhelk Dja: Safe Our Way – Strong Culture, Strong Peoples, Strong Families (the Dhelk Dja Agreement), that addresses family violence in Aboriginal communities. It is informed by the self-determination principles within Korin Korin Balit-Djak, Victoria’s Aboriginal health, wellbeing and safety strategic plan 2017–2027.

The Dhelk Dja Agreement commits the signatories – Aboriginal communities, Aboriginal services and government – to work together. It commits them to be accountable for ensuring that Aboriginal people, families and communities are stronger, safer, thriving and living free from family violence. The Dhelk Dja Agreement is at the centre of family violence reform initiatives affecting Aboriginal people.

The Dhelk Dja Partnership Forum and its members are strategic leaders overseeing the implementation of the Dhelk Dja Agreement. The forum works closely with community and stakeholders.

Rolling Action Plan activities will continue to progress family violence reforms, in line with the Dhelk Dja Agreement.

What has happened

What is next

We will continue many activities started over the past two years:

- Work has commenced to deliver the Aboriginal Family Violence Primary Prevention Research Project. This will examine existing initiatives and inform effective primary prevention of violence experienced by Aboriginal Victorian women, children and their families. This research will inform the review and update of the Indigenous Family Violence Primary Prevention Framework.

- Work will commence on developing frameworks to ensure the voices of Aboriginal children and young people and Elders are embedded in the system transformation work.

- A forum will be held in 2022 showcasing the successful Aboriginal community-led prevention initiatives to inform communities and share best practice.

- Discussions will continue to inform an approach for a campaign focused on preventing violence against Aboriginal women, children and families.

- The refresh and expansion of the Police and Aboriginal Community Protocols against Family Violence sites will continue. Co-design and delivery is informed by the Dhelk Dja Regional Action Groups, Regional Aboriginal Justice Advisory Committees and the community.

- A 10-year investment strategy will be developed in partnership with Koori Caucus members of the Dhelk Dja Partnership Forum to inform the 2022–23 budget cycle.

- Work is progressing to inform the Aboriginal data needs project to support baseline understanding of Aboriginal family violence prevention activities and build the evidence base for prevention and early intervention. This will support the Koori Caucus of the Dhelk Dja Partnership Forum to prioritise investment and activity towards identified need.

What this means for outcomes

Housing priority area

Improving access to safe and stable housing options

Understanding and responding to the housing needs of people experiencing and using family violence is a key part of the family violence reform.

Meeting the housing needs of Victorians experiencing family violence is complex. Each victim survivor has different needs and considerations.

Emergency accommodation may be important in a crisis. However, many victim survivors want support to stay in their own homes. Those who cannot stay at home need assistance beyond short-term refuge. A stable home in a suitable location provide security and support stable work and education.

In addition to delivering better outcomes for individuals, timely access to stable long-term accommodation reduces the blockages in refuge and crisis accommodation.

Our focus continues to minimise risk during crises. We do this by supporting victim survivors to exit safely from a family violence situation. We are also delivering long-term solutions to re-establish stability for victim survivors, including children.

The focus for the Rolling Action Plan involves new activity and continued delivery of the significant long-term housing investments announced. This includes continuing to replace our communal refuges with new core and cluster model refuges providing greater privacy and independence and building more new social housing homes.

What has happened

Family violence is a leading cause of homelessness, especially for women and children. Homelessness can occur as a direct result of experiencing family violence and structural barriers. These barriers include gender inequality, a lack of affordable housing, and limited social support.

Victoria has commenced delivery of the Big Housing Build, which aims to increase social and affordable housing. On completion, it will deliver more than 9,300 social housing dwellings:

- 1,100 dwellings will replace existing stock,

- 8,200 will be new social housing dwellings, and

- 2,900 will be new affordable market homes.

Home ownership offers great protections against family violence and gives victim survivors a chance to gain financial independence. The Big Housing Build is expected to provide a safe home for 1,000 victim survivors of family violence across Victoria. This investment is on top of the $498 million Building Works package for refurbishment and maintenance of existing public and community housing properties. The Building Works package includes a $10 million investment to increase support for women and children escaping family violence.

The Royal Commission found that housing pathways for victim survivors are ‘blocked up’ and not flowing as intended. It recognised that these blockages result in women and children remaining in refuges for longer periods. Over the past two years, the average length of stay for victim survivors in refuge has remained relatively stable (6.2 weeks in 2019–20 and 6.4 weeks in 2020–21).

Victorian private rental laws were updated in March 2021. These included higher protections for victim survivors and accountability for perpetrators of family violence:

- The Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal can now assist in removing perpetrators of family violence from rental agreements. This allows victim survivors and their children to remain in their own homes.

- Victim survivors are not liable for damage caused by a perpetrator of family violence who does not live in the home.

- Termination of rental agreements because of family violence must be heard by the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal within three business days.

Our focus on the future of Victoria’s crisis accommodation continues to be the core and cluster model.

This includes 19 redeveloped and new family violence refuges across Victoria, including three new Aboriginal-specific refuges. The core and cluster model provides individual family units with on-site support which will provide greater independence, privacy and security for victim survivors, including children. As refuges are redeveloped, capacity for after-hours support will also be provided.

What is next?

Through 2022 the planning, redevelopment and construction of refuges and dwellings will continue. This includes:

- continuing the redevelopment of 10 family violence refuges including the completion of a second Aboriginal-specific family violence refuge and the commencement of a third

- construction of new public housing dwellings

- delivery of an additional 18 new social housing dwellings under the Social Housing Growth Fund

- consultation on the Benalla masterplan for the Regional Estate Revitalisation project

- acquisition of a further 18 properties for women and their children.

We will also evaluate the Medium-Term Perpetrator Accommodation Service and determine next steps based on the key learnings and outcomes from the five pilot sites.

The social and affordable housing challenge will require ongoing effort over many years, extending beyond the Big Housing Build. That is why we are developing a new 10-year Strategy for Social and Affordable Housing in Victoria. We are committed to ensuring all Victorians have access to a safe, affordable and appropriate home. The new strategy will establish the 10-year vision for social and affordable housing in Victoria and build on the success of the Big Housing Build and other investment to date. What this means for outcomes

Legal assistance priority area

Improving legal assistance access, representation and integration across the family violence system

This priority area focuses on improving access to legal assistance and representation. It also enhances integration between the legal assistance sector (such as Victoria Legal Aid) and the broader family violence service system.

These activities focus on early intervention, workforce capacity and responding to the impact of COVID-19.

They support victim survivors to understand their legal options and make informed decisions about their family and safety needs and to advocate for their access to justice. They also help perpetrators understand police and court processes and meet any obligations associated with court outcomes.

The Family Violence Legal Assistance Working Group (co-chaired by the Department of Justice and Community Safety and the Federation of Community Legal Centres) determined the order and priority for delivering these activities in 2022 and 2023. The working group took into consideration the demands on the sector as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and the breadth of work committed to.

What has happened?

There has been some progress towards implementing Rolling Action Plan activities within the legal assistance priority area. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic across the legal system were significant. As a result, we focused on the immediate delivery of services, rather than broader reform to improve legal assistance access, representation and integration across the family violence system.

The Legal assistance priority area is closely aligned with the Courts priority area. In particular, this occurs through activities, services and programs provided through the Specialist Family Violence Courts.

What is next

We are considering and prioritising a number of activities in the legal assistance area delivery commencing in 2022. This will provide clear direction for the sector on what will be delivered.

There are some activities already in progress that will continue, including:

- a broad piece of work to respond to the needs of adolescents who use family violence. This would consider the recommendations from the Positive interventions for perpetrators of adolescent violence in the home report

- working with legal services to ensure that training aligns with the Family Violence Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management (MARAM) Framework

- working to establish a statewide approach to the connection and coordination of legal services within The Orange Door network in every area, following the commencement of the pilot. Development of an agreed and consistent service connection with legal services across the Orange Door network will continue following the outcomes of the pilot.

What does this mean for outcomes

MARAM and information sharing priority area

A shared approach to risk assessment and information sharing

The Family Violence Multi Agency Risk and Assessment Management (MARAM) Framework, the Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme, the Child Information Sharing Scheme, and the Central Information Point support an effective and consistent approach to risk assessment and management. They also increase collaboration between services through information sharing.

Having a shared understanding supports:

- successful system integration

- workforces who understand their responsibilities in identifying and responding to family violence

- an accessible, equitable system response.

The focus of the Rolling Action Plan is to continue to implement and embed the MARAM Framework. This will include working with organisations and services who do not primarily deal with family violence as part of their service provision. These organisations and services will nonetheless encounter family violence. They need to know how to respond and support victim survivors, as well as raising whole of system capability and confidence in keeping perpetrators in view and accountable. This includes collaborating with, or referral to other services and contributing to risk management.

MARAM Framework

MARAM is the cornerstone of the government’s family violence risk assessment and management reform. It provides evidence-based guidance and tools to professionals to help consistent and collaborative responses to family violence.

With the roll out of Phase 2 of the MARAM over 370,000 practitioners (as at April 2021) are now prescribed from organisations across the health, education, justice and social service system. This means that along with the family violence workforce, other workers will use MARAM as part of their work. This includes workers in primary and secondary schools, early childhood education and care services, community-managed mental health and housing services, public health services and hospitals, refugee and migrant services and state-funded aged care services.

So far, more than 62,000 workers have been trained in MARAM and the information sharing schemes. The bulk of prescribed workers became prescribed in April 2021.

Practitioner reflections from the Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency

The new MARAM tools provide a holistic framework to assist with identifying current risk as well as any historical intergenerational trauma. This allows practitioners to design healing plans that respond to a family’s whole experience of family violence.

Practitioners state that the risk assessment tool is useful therapeutically to open up conversations about family violence.

A key aspect of this is how the tool supports the practitioner to continue to hear what the client is saying. This means they are less likely to make a binary judgment or have an attitude that might lead them to predict culpability at the outset about who may be using or experiencing harm.

Rather than being used in a single session, practitioners find that it works best when used over a series of sessions. It can also be revisited to reflect on shifts that have taken place around dynamic risk and safety.

The Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme is a key enabler of MARAM. It enables prescribed organisations, known as Information Sharing Entities, to facilitate assessment and management of family violence risk to children and adults. The Child Information Sharing Scheme enables the broader sharing of information to promote child wellbeing or safety including in the absence of family violence.

What has happened

What is next

- We will continue to implement the MARAM Framework, Practice Guides and resources across prescribed organisations and services.