June 2024

Notable market developments

- Prices for recovered PET bottles started low in 2023–24 but rose across the financial year. At the start of 2023-24, PET packaging scrap prices fell to around the $200–$250 per tonne, in comparison with values of around $420–$500 per tonne at the end of 2022-23r. The PET export price saw strong growth across the financial year with average values in February and March 2024 of close to $520 and $735 per tonne, respectively.

- Prices for recovered HDPE bottles have remained strong but had also dipped at the start of 2023–24. The average HDPE packaging scrap price in September 2023 was close to $855 per tonne, this increased to over $1,000 per tonne by March 2024.

Material overview and market summary

Overall plastic recovery remains low. This is due to the cost recover and process plastics to a quality equivalent to virgin material higher than the cost of the virgin fossil fuel-based plastics for most polymers.

Since 1 July 2022 rPET and rHDPE must be flaked and washed (at a minimum) to be exported. This has resulted in downward pressure on unprocessed bale prices as local reprocessing capacity catches up with the available local supply. However, prices for rHDPE have continued to remain resilient, reflecting the adequate scale of local reprocessing capacity and many local end-market applications for this material.

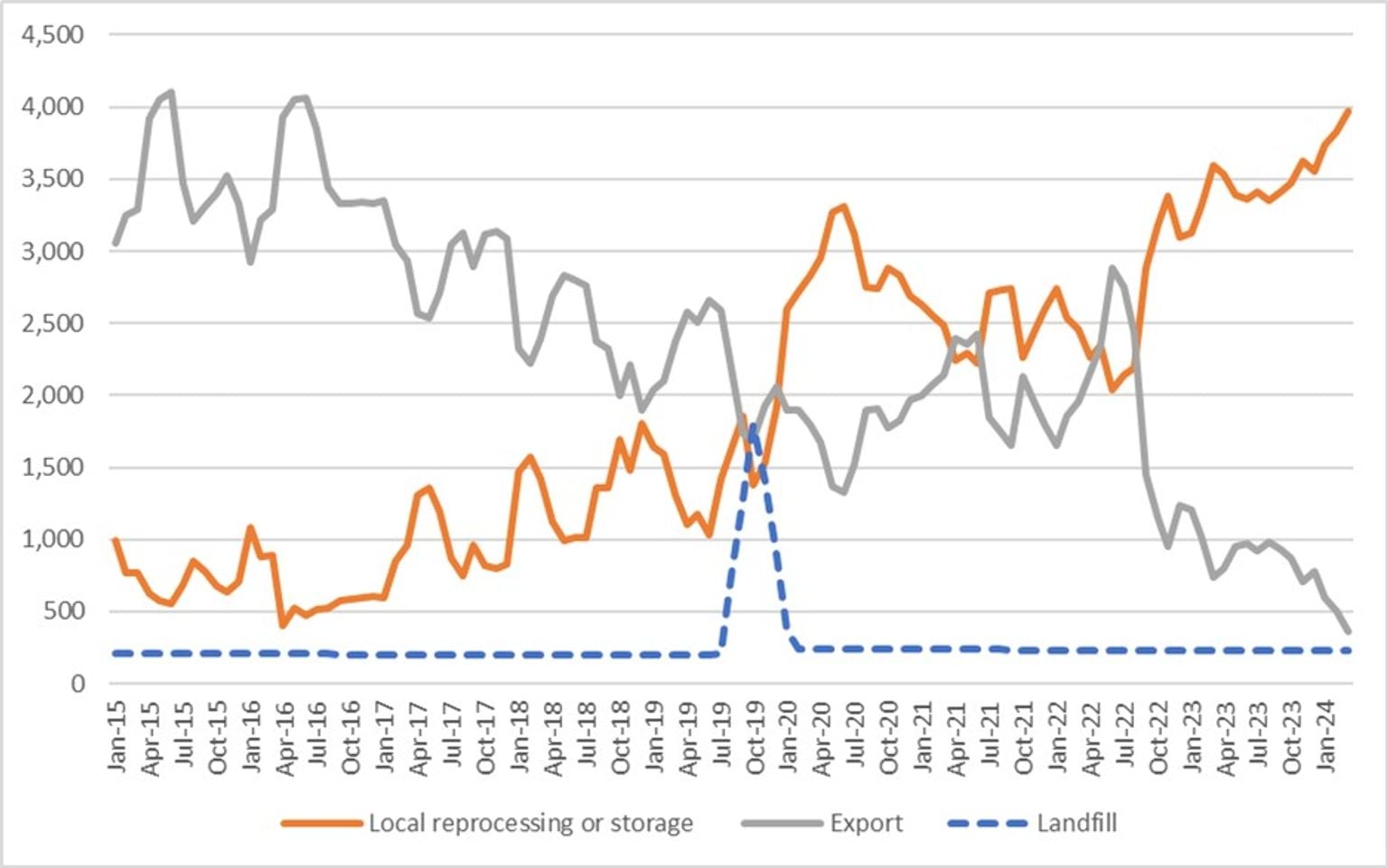

Figure 1 shows the change in exports of kerbside recovered plastic packaging since the beginning of 2015. From April to June 2022 there was a significant jump in exports, this led up to the 1 July 2022 export ban on unprocessed single-polymer scrap plastics. From July 2022 there has been a fall in exports of unprocessed (kerbside sourced) rigid plastic packaging (sorted into single polymer grades), which has continued through to March 2024.

Prices, demand, and supply

There continues to be strong local and export markets for clean PET beverage packaging bales that are collected, sorted and reprocessed to specification. Prices fell at the start of 2023–24 to around the $200–$250 per tonne mark, compared to values of close to $420–$500 per tonne at the end of 2022-23. The PET export price saw strong growth across the financial year with average values in February and March 2024 of close to $520 and $735 per tonne, respectively.

Prices for clean HPDE bales have generally been in the range of $900–$1,100 per tonne since the beginning of 2022. This has been underpinned by the very strong local and international brand owner demand for packaging grade rHDPE. Prices in 2023–24 followed a similar trend to PET, with a dip towards the start of the financial year followed by growth. In September 2023, the HDPE bale price was about $855 per tonne, but it increased to over $1,000 per tonne by March 2024. The requirement to reprocess the HDPE locally does not appear to be putting any notable downwards pressure on the price of unprocessed HDPE packaging bales.

Key end markets and related specifications

Exported plastic packaging has specifications relating mostly to contamination levels. The sorting of PET, HDPE and PP from kerbside collection, undertaken at MRFs allows the baled material to generally meet these specifications without major difficulty or manual sorting input. However, as outlined above, from July 2022 the single polymer sorted bales need to be reprocessed (chipped and washed at a minimum) to be exportable under the bans.

Export and interstate market review

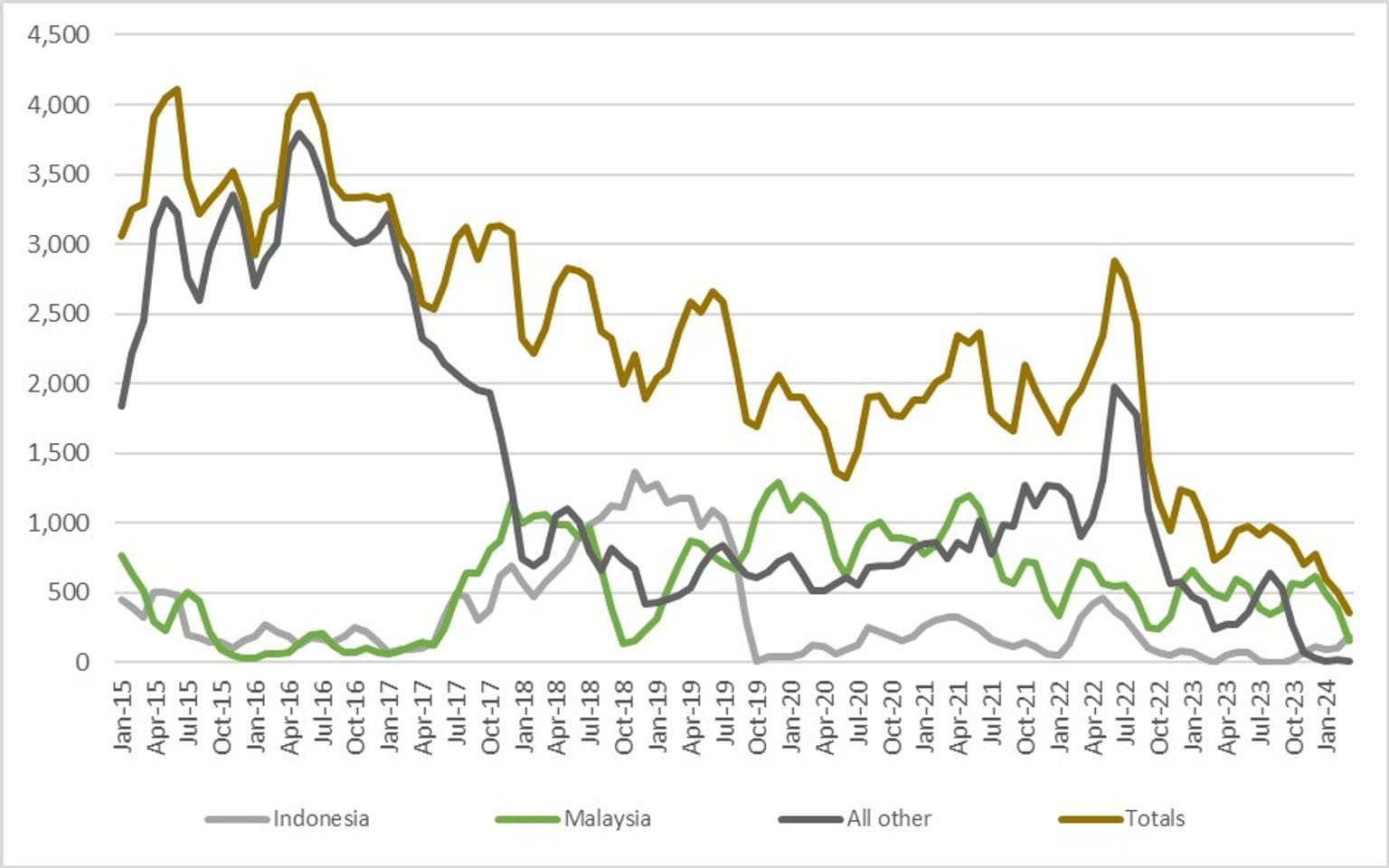

Until restrictions in 2018, plastic packaging was exported to China. During the 2018–19 financial year Indonesia was the major destination. Since September 2019 Malaysia has been the largest destination for Victoria kerbside plastics.

Post-consumer plastic imports into Malaysia from Victoria have been trending down since the beginning of 2019 until March 2024, but with large monthly variability. Across the 2023–24 financial year so far (July 2023 to March 2024) exports to Malaysia made up about 60% of total exports, with total exports falling dramatically since July 2022.

Victoria continues to be highly exposed to Malaysian import conditions, albeit at a much lower level than the historical levels of exposure to China and then Indonesia.

The export bans in force since July 2022 have largely ended the export of any unprocessed plastics from Australia, with the major exception of LDPE pallet wrap film, collected from commercial and industrial generators.

Table 1: Annual Victorian recovered kerbside plastic packaging, to export country (tonnes per year)

| Country* | 2015–16 (tonnes) | 2016–17 (tonnes) | 2017–18 (tonnes) | 2018–19 (tonnes) | 2019–20 (tonnes) | 2020–21 (tonnes) | 2021–22 (tonnes) | 2022–23 | 2023–24** (tonnes) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Country* Indonesia | 2015–16 (tonnes) 2,100 | 2016–17 (tonnes) 2,000 | 2017–18 (tonnes) 6,900 | 2018–19 (tonnes) 13,700 | 2019–20 (tonnes) 2,700 | 2020–21 (tonnes) 2,900 | 2021–22 (tonnes) 2,500 | 2022–23 1,100 | 2023–24** (tonnes) 600 |

Country* Malaysia | 2015–16 (tonnes) 1,900 | 2016–17 (tonnes) 1,400 | 2017–18 (tonnes) 10,600 | 2018–19 (tonnes) 6,600 | 2019–20 (tonnes) 11,600 | 2020–21 (tonnes) 11,600 | 2021–22 (tonnes) 7,300 | 2022–23 5,700 | 2023–24** (tonnes) 3,900 |

Country* All other | 2015–16 (tonnes) 37,700 | 2016–17 (tonnes) 34,400 | 2017–18 (tonnes) 16,200 | 2018–19 (tonnes) 7,500 | 2019–20 (tonnes) 7,800 | 2020–21 (tonnes) 9,300 | 2021–22 (tonnes) 14,100 | 2022–23 8,800 | 2023–24** (tonnes) 2,100 |

Country* Total | 2015–16 (tonnes) 41,700 | 2016–17 (tonnes) 37,800 | 2017–18 (tonnes) 33,700 | 2018–19 (tonnes) 27,800 | 2019–20 (tonnes) 22,100 | 2020–21 (tonnes) 23,800 | 2021–22 (tonnes) 23,900 | 2022–23 15,600 | 2023–24** (tonnes) 6,600 |

Source: ABS and IE (Australian Harmonized Export Commodity Classification (AHECC) data by month, classification and destination country, 2023) and Blue Environment.

* Countries ranked by average of last 3 months of exports.

** Partial year to March 2024.

Table 2: Most recent monthly change in Victorian kerbside recovered plastics, to export country

| Country | July 2024 (tonnes) | August 2024 (tonnes) | Change (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

Country Indonesia | July 2024 (tonnes) 100 | August 2024 (tonnes) 200 | Change (%) 100% |

Country Malaysia | July 2024 (tonnes) 400 | August 2024 (tonnes) 200 | Change (%) -50% |

Country All other | July 2024 (tonnes) 0 | August 2024 (tonnes) 0 | Change (%) N/A |

Country Korea | July 2024 (tonnes) 500 | August 2024 (tonnes) 400 | Change (%) -20% |

Source: ABS and IE (Australian Harmonized Export Commodity Classification (AHECC) data by month, classification, and destination country, 2024) and Blue Environment.

Market opportunities

There continues to be significant and growing local demand for high-quality PET, HDPE and PP packaging recyclate for remanufacturing into many applications (if reprocessed to a high level). In addition, export markets exist for high quality sorted/washed flake and pellets, with price premiums available at around 50%–100% the price of virgin resin.

There is significant new rPET, rHDPE and rPP reprocessing capacity in the pipeline, that appears close to covering the local reprocessing shortfall, including scrap plastics caught up in the Australian unprocessed single-polymer plastics export ban that came into force as of 1 July 2022. Most of this has come into operation or will come into operation across 2024.

Markets for mixed polymer and lower value post-consumer plastic packaging, such as PET thermoforms, rigid PVC, rigid PS, and mixed polymer scrap bales continue to be underdeveloped or non-existent. It is understood that most of this material continues to be sent to landfill.

Continued deselection of PVC and PS, and ongoing improvements in PET, HDPE and PP based packaging design, are anticipated to improve the overall value and recyclability of our PET, HDPE and PP dominated rigid plastic packaging system.

Report disclaimer

The information in this report was prepared in conjunction with Blue Environment.

While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, Recycling Victoria gives no warranty regarding its accuracy, completeness, currency or suitability for any particular purpose and to the extent permitted by law, does not accept any liability for loss or damages incurred as a result of placed upon the content of this publication.

This publication is provided on the basis that all persons accessing it undertake responsibility for assessing the relevance and accuracy of its content.

Recycling Victoria does not accept any liability for loss or damage arising from your use of or reliance on the Data. The inclusion of information in this report does not constitute Recycling Victoria’s endorsement of any particular facility or any associated organisation, product, or service.

Accessibility disclaimer

The Victorian Government is committed to providing a website that is accessible to the widest possible audience, regardless of technology or ability.

This page contains two embedded complex image files (Figures 1 and 2) that may not meet our minimum WCAG AA Accessibility standards.

If you are unable to read any of the content of this page, you can contact the content owners for an accessible version.

Contact email: rvdata@deeca.vic.gov.au

Updated