Download a copy of the HCD Playbook here!

What is human-centred design?

Human-centred design (HCD) is an approach to problem-solving that puts the people we are designing for at the heart of the process.

The human-centred design process begins with empathy for the people we are designing for. The process:

- generates a wide variety of ideas

- translates some of these ideas into prototypes

- shares these prototypes with the people we’re designing for to gather feedback

- builds the chosen solution direction for release

The goal of employing human-centred design is to develop solutions that meet the needs of Victorians.

Human-centred design is an iterative practice that makes feedback from the people we’re designing for a critical part of how a solution evolves.

By continually validating, refining and improving our work we can discover the root causes of knotty problems, generate more ideas, exercise our creativity and arrive more quickly at fitting solutions.

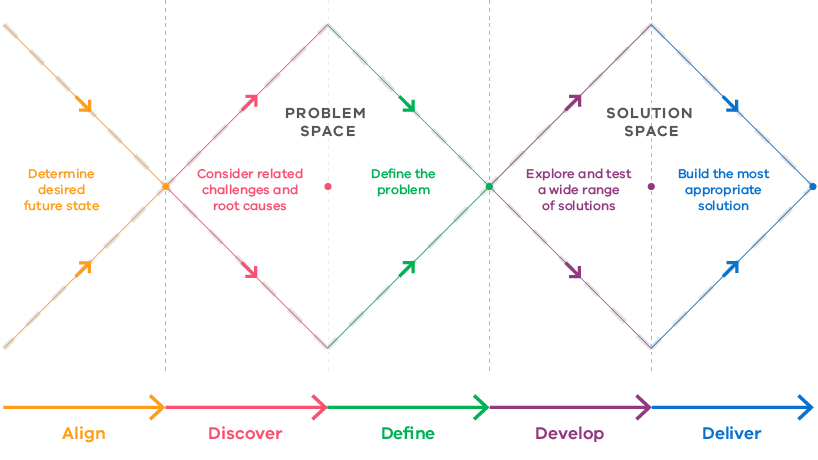

Our design process

Why use human-centred design?

When executed well, an HCD approach leads to the creation of government services that align with people’s needs and desires. Involving end users in the overall design process leads to greater buy-in and impact.

Benefits for the people of Victoria

- Improved policy, services and products that help address the needs of Victorians.

- Reduced transactional friction when using government products or services.

- Reduction of thought overload when determining how to use government services.

Benefits for the government of Victoria

- Provides a citizen perspective of the problem at hand (an outside-in approach).

- Reduces the risks of a ‘failed’ policy, product or service through validation.

- Paints a clearer picture of the wider context in which the problem lies.

- Reduces costs by building more targeted systems and services that meet the needs of people.

- Creates a positive reputation and increased trust in government through greater engagement.

- Can increase productivity and improve operational efficiency.

- Builds organisational resilience through an agile and iterative process.

- Helps the VPS understand the Victorians affected by their decisions.

Public sector problems are different

As public servants, our aims are generally geared toward improved social outcomes, which differs greatly from the financial aims of private entities. Because our aims are different, the way we measure success is also different.

Some of the things that make public sector challenges unique include:

- serving diverse, poorly resourced and vulnerable populations

- engaging multiple stakeholders who share decision-making power but hold different or conflicting interests

- delivering services more than products

- delivering at scale from the beginning to reach a large population of beneficiaries

- compliance to high degrees of privacy protections and safeguards

- creating long term change within time-bound administrative periods and priorities

With these things in mind, we need to consider how human-centred design is employed differently in the public sector, taking greater care in the early stages of discovering and defining the problem.

Thankfully, there are various frameworks we can use during the act of ‘problematising’ that are aligned to HCD principles.

The Adaptive Leadership model

One of these frameworks is Heifetz and Linsky’s Adaptive Leadership model, which describes challenges as either adaptive or technical.

A technical challenge can be resolved with subject matter knowledge and experts (such a building a bridge).

Adaptive challenges are dynamic, unpredictable, seemingly irrational and requires new learning and change in beliefs. Public sector challenges are more adaptive than technical, due in large part to the social dimensions mentioned above.

The Cynefin framework

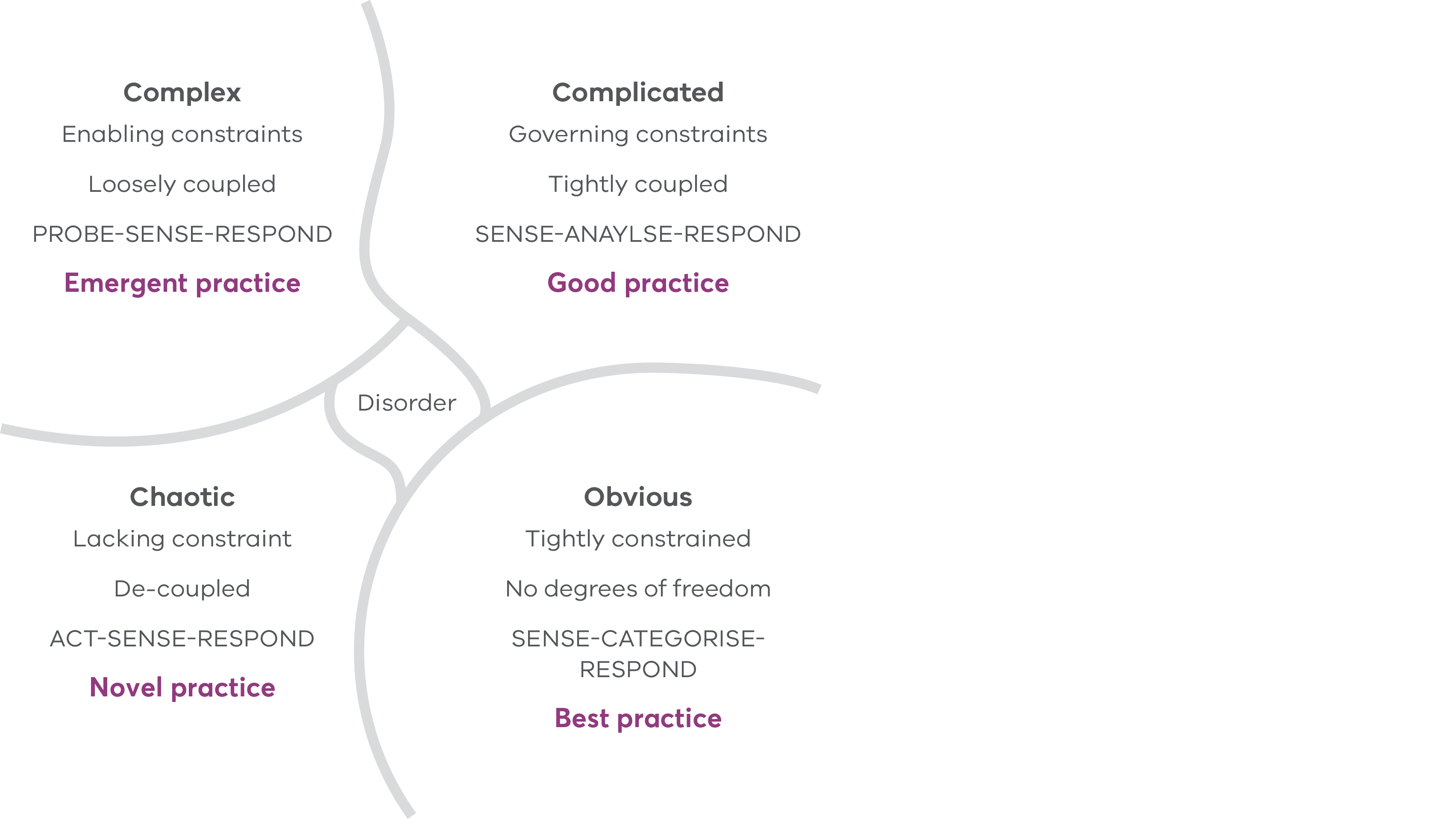

Another is the Cynefin framework (pronounced kuh-nev-in) by David Snowden. This framework helps sort challenges into five categories: obvious, complicated, complex, chaotic or disorderly, and outlines what response is best suited to each category.

Many public sector challenges fall into the complex category, particularly as they are multi-stakeholder, ever-changing, and need to account for human behaviour, emotions and habits.

This makes them more dynamic than those that fall in the complicated category, where problems may be more technical and predictable.

Like the Adaptive Leadership model, the Cynefin framework describes how complex challenges require a probe-sense-respond approach.

What Adaptive Leadership, Cynefin and HCD approaches share is a belief that fully understanding and appreciating the problem is the most important part of the work, requiring a commitment to an experimental and learning mindset.

Divergent and convergent thinking

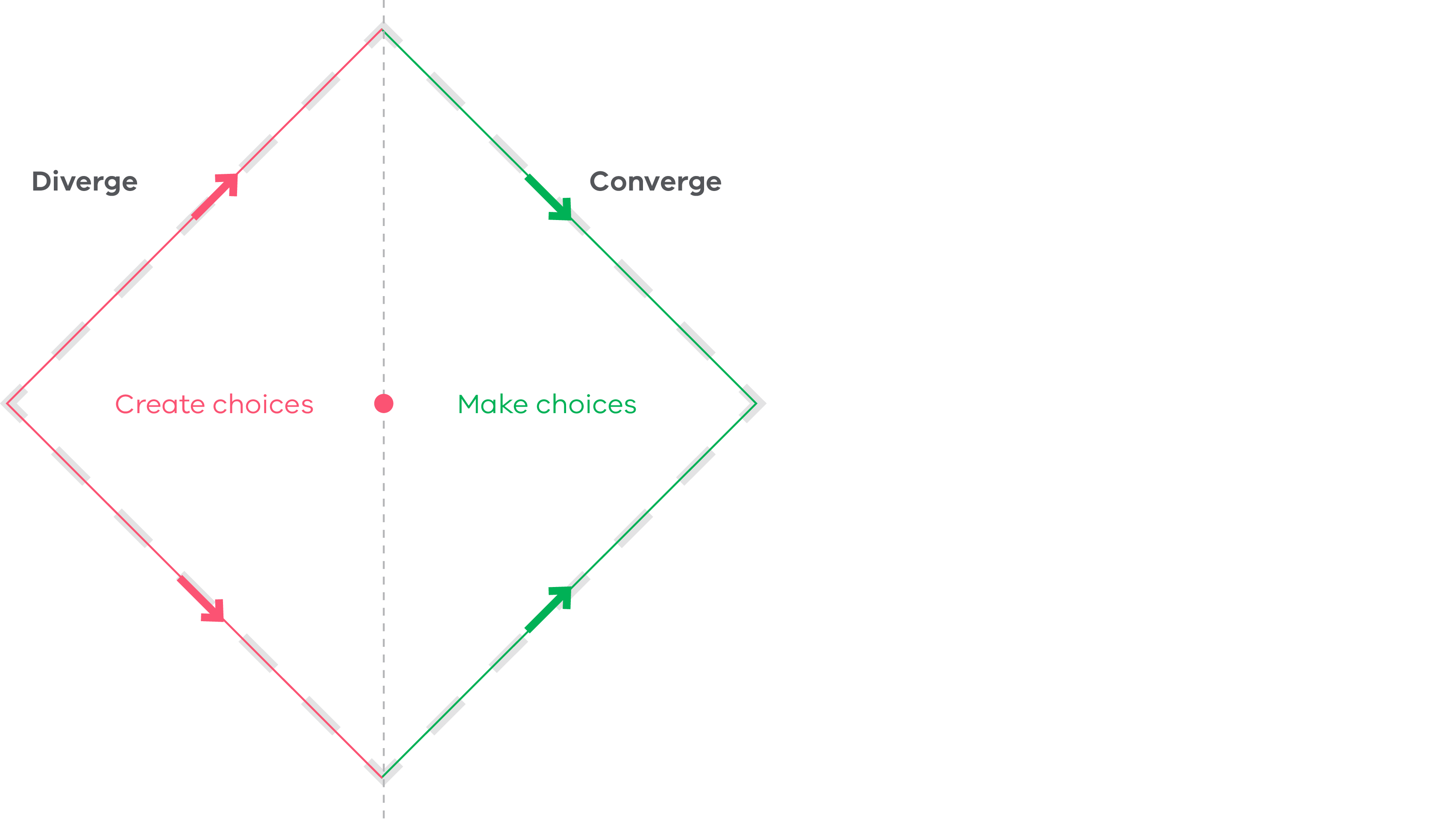

Our design process, based on the Double Diamond framework by the UK Design Council, has periods that are divergent and convergent. Divergent periods, such as Discover and Develop, are for trying many approaches: asking ‘what could be’ and being open to where the work might take you without deep review or analysis.

Convergent periods, such as Align, Define and Deliver, are periods of evaluating, articulating and making choices around what to pursue. Successful HCD projects dedicate a healthy amount of time for both divergent and convergent periods.

Due to the time pressures and limited resources in the public sector, we too often sacrifice the divergent periods of possibilities and commit quickly to a known solution, reusing past ideas not necessarily because they’re the best, but because it’s been done before.

This approach to project delivery stifles innovation as we fail to exercise our imagination. Recycling ideas for new contexts and problems can lead to diminishing levels of success and sub-optimal results.

Competitive organisations need to be adaptable, forward leaning and creative. The design process affords the opportunities and processes to take a fresh perspective on the problem and what’s possible.

Analytical and design approaches

A traditional analytical approach is linear and requires a heavy investment early in the process during the deep analysis of a question, which then leads to a highly informed answer.

But what if the problem was misunderstood and framed the wrong way from the beginning? A lot of time and energy will have been spent discovering the root issues to the wrong question, leading to a highly refined but ill-fitting solution.

In the non-linear design approach, you spend the early stages of the process discovering the true problem.

Instead of over-analysing the problem from an expert mindset or an institutional understanding, the human-centred design process encourages you to hold a learning mindset and understand a citizen’s experience. You quickly and cheaply test hunches and observe how the stakeholders react to your ideas and how the ideas fit the context. The intent is to allow the true problem to reveal itself as you validate or invalidate your assumptions, while developing a richer understanding of the context.

Once you’ve outlined the problem you can move just as quickly through the solutioning stages. This stage helps further articulate the question or problem as you begin testing various solutions. This is the essence of prototyping – accelerated learning about the problem and solution at the same time.

Reducing cost and increasing efficiency

You can use a human-centred design approach to increase government efficiency in several ways.

Addressing the right problem

The human-centred design process provides stakeholders with a very clear definition of the problem to be addressed. Designing a program without an established and shared understanding of a problem can be extremely costly and time-consuming if it ends up solving the wrong or a non-existent problem.

Testing ideas cheaply and quickly

The human-centred design avoids ‘big bets’ through rapid prototyping, iteration and A/B testing.

This is a major shift from the waterfall approach, which treats analysis, design and implementation as discrete and sequential phases in a project. In the waterfall approach, large resources are commonly dedicated to product or service development without user testing.

Using human-centred design (HCD), you get quick and frequent feedback from users as you go and reduce the financial and reputational risks of failure.

Reducing support costs

The more user-friendly a system is, the less time you need to teach users how to use it, which increases adoption. If HCD methods are performed thoughtfully, the system you’ve designed should be as frictionless and autonomous as possible, which means fewer complaints need to be handled and therefore less resources spent on customer service.

Building capacity and working across silos

As HCD often involves multidisciplinary teams, running a project in this way encourages working across department and entity silos and with a wide set of stakeholders.

Gathering input from many sources and cross-fertilisation of ideas helps to build capacity and social capital that can spill over into adjacent and future projects.

Engaged citizens

As public servants we aim to improve and empower citizens in their democratic life in Victoria. A human-centred design approach contributes to strengthening the relationship between government and citizens in specific ways.

Understanding the citizen perspective

As the lives, rituals and behaviours of citizens change so too will their needs. We need to understand the challenges faced by citizens to know how we can most appropriately respond. Understanding citizens’ perspectives informs policy- and decision-makers and can be translated into services and programs that citizens will engage with.

Human-centred design is a means to develop a rich understanding of citizens experiences in order to increase program effectiveness by developing novel solutions or improving existing designs.

Improving citizen experiences

Products, services, systems and programs that are user-friendly, accessible and equitable create enormous benefits for Victorians. They save time and remove barriers to access, meaning citizens get the services and support they need, when they need it. An HCD approach ensures users can use services effectively and efficiently.

Guiding principles of human-centred design

Engaging directly with members of the public may be new and challenging, particularly when working with vulnerable communities. In order to get the most out of HCD-led work we recommend approaching your work in the following ways:

Dignified

How do I value people as unique collaborators and honour lived experience, culture and strengths?

Attentive

How do I plan to attend to my own needs and others’ needs?

Relational

How do I facilitate trust and a spirit of willing participation?

Truth-telling

How do I adopt authenticity and truthfulness, even when it’s difficult?

Aware

How do I become aware of power and how do I discuss, negotiate and share it?

Trustworthy

How do I take care with the stories and information that are given to me?

Risk and reward

Taking a human-centred design approach can feel risky – especially if it’s a new way of working. However, the core intent of HCD is to de-risk a project through a structured process that delivers more fitting solutions.

When you invest time at the beginning of a project to better understand the problem and users’ needs, you’re able to amend and fine-tune solutions while it’s still cheap and easy to do so. You’ll avoid overinvestment in ill-fitting solutions. It’s an effective and efficient approach that saves time, resources and effort.

Putting it into practice

The methods and tools in this playbook offer a starting point for planning and scoping your human-centred design project.

We provide descriptions, tips and budget and timeline expectations for common HCD methods and outputs. These methods will take you from framing up your design challenge to getting your solutions out into the world.

You’ll probably use some of these methods several times and some rarely or never.

They’ll get you into the habit of continuously advancing your work while keeping the community you’re designing for squarely at the centre of your work.

Updated